2025 was a less chaotic year for me—literally and psychologically—than 2024. I wish I could say that this meant I read more and better, but instead both my memory and my records show that it was a pretty uneven reading year, with a lot of slumps. The summer especially, which used to be a rich reading season for me, had almost no highlights: the best books I read in 2025 were at the very beginning and the very end of the year.

2025 was a less chaotic year for me—literally and psychologically—than 2024. I wish I could say that this meant I read more and better, but instead both my memory and my records show that it was a pretty uneven reading year, with a lot of slumps. The summer especially, which used to be a rich reading season for me, had almost no highlights: the best books I read in 2025 were at the very beginning and the very end of the year.

Best of 2025

Three books I read this year were truly extraordinary experiences. One was Anne de Marcken’s astonishing and heartbreaking zombie novel (yes, you read that right) It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over. I have thought about this novel over and over since I finished it. How much can we lose, it asks, before we lose ourselves? In a world characterized by loss, what makes us keep on moving? If you are sure, as I was, that a novel about zombies is not for you, maybe think again.

A wind comes up to me in the empty morning like someone I’ve met before or seen before but don’t know, and a feeling comes over me. It is sadness. Not a sadness, but sadness. All of it. The whole history of sadness. Everything in me is sad and everything around me is a part of it. The cracked pavement, the moon, the abandoned cars, the gravity that holds them to the road. It is total. I am taken, or taken down. I drop to my knees.

Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book could hardly be more different in topic, style, or tone, but it too is about loss and death and persistence. It is a historical novel but also a time-travel novel; mostly I find the illogic of time travel too much of an impediment to emotional commitment, but in this case the framing added layers of historical and philosophical ideas that added to rather than distracted from the immersive storytelling of the 14th-century sections. Reading it reminded me of Raymond Chandler’s remark that once a detective novel is as good as The Maltese Falcon, it is foolish to say it can’t be even better: speculative fiction is not a go-to genre for me, but Willis showed me that it’s not the genre itself that’s the barrier. (That said, I stalled out in my subsequent attempt to read her novels about the Blitz, which I started to find tedious—they are staying on my shelves, though, so that I can give them another chance at some point.)

Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book could hardly be more different in topic, style, or tone, but it too is about loss and death and persistence. It is a historical novel but also a time-travel novel; mostly I find the illogic of time travel too much of an impediment to emotional commitment, but in this case the framing added layers of historical and philosophical ideas that added to rather than distracted from the immersive storytelling of the 14th-century sections. Reading it reminded me of Raymond Chandler’s remark that once a detective novel is as good as The Maltese Falcon, it is foolish to say it can’t be even better: speculative fiction is not a go-to genre for me, but Willis showed me that it’s not the genre itself that’s the barrier. (That said, I stalled out in my subsequent attempt to read her novels about the Blitz, which I started to find tedious—they are staying on my shelves, though, so that I can give them another chance at some point.)

I read both of these books in January; although I read some other good books over the year, the third really exceptional one was Marlen Haushofer’s The Wall, which I finished in December. I suppose it too is a kind of speculative fiction, an eerie “what if” scenario that leads to a novel that if I were a drunk publicist I would pitch as “May Sarton’s existential wilderness adventure.” Once again a key theme is persistence: in this case, literal and physical—she has to feed herself and take care of animals and stay warm—but also metaphysical, as inevitably she asks questions about why she should do any of that, and about the value of everything people do. It is hard to describe this book in a way that captures why it is engrossing and exhilarating rather than dreary but it is.

Also Very Good

My ‘also rans’ list is strong this year, if not that long.

Non-Fiction

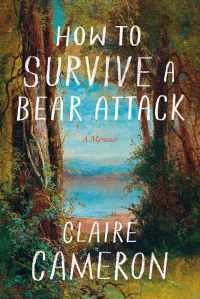

The best non-fiction I read was Claire Cameron’s memoir How to Survive a Bear Attack. Yes, it is actually about how to survive a bear attack, but it is also about confronting fear and illness and death.

The best non-fiction I read was Claire Cameron’s memoir How to Survive a Bear Attack. Yes, it is actually about how to survive a bear attack, but it is also about confronting fear and illness and death.

Yiyun Li’s Things in Nature Merely Grow is as hard-headed and devastating as her previous writings about suicide—more so in a way, because this is about her second son to die by suicide. Ordinarily I don’t dislike sentimentality, and there’s a coldness to Li’s voice that is sometimes alienating, but there is also something bracing about her clarity and her refusal to cater to people’s desire for there to be meaning where she finds none, or for grieving parents to offer those around them implicit solace by seeming to get over it, “as though bereaved parents are expected to put in a period of hard mental work and then clap their hands and say, I’m no longer heartbroken for my dead child, and I’m one of you normal people again.” The line from this book that has echoed in my head since I read it is so simple and obvious it might seem strange that it has so much power for me: “children die, and parents go on living.”

An honourable mention definitely goes to Chloe Dalton’s Raising Hare.

Fiction

Other novels that really stood out to me this year:

Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional

Salena Godden’s Mrs. Death Misses Death

Rumer Godden’s Black Narcissus

Helen Garner’s The Spare Room

Carys Davies, Clear

Ian McEwan, What We Can Know

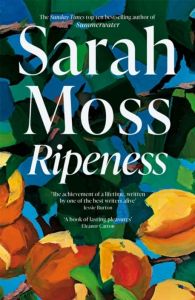

A near miss: Sarah Moss’s Ripeness. As I said in my post about it, “I would not say I loved the novel, but I have never read anything by Moss that isn’t both meticulously crafted and convincingly intelligent.” Moss remains an auto-buy for me; perhaps anything would have been a bit of a let-down after the extraordinary memoir she published last year, My Good Bright Wolf.

A near miss: Sarah Moss’s Ripeness. As I said in my post about it, “I would not say I loved the novel, but I have never read anything by Moss that isn’t both meticulously crafted and convincingly intelligent.” Moss remains an auto-buy for me; perhaps anything would have been a bit of a let-down after the extraordinary memoir she published last year, My Good Bright Wolf.

I did a fair amount of what I call “interstitial reading” in 2025—books I can easily pick up and put down in between work or chores, or before bed. This year these were mostly romances or ‘women’s fiction,’ writers like Abbie Jimenez and Katherine Center. I didn’t read many mysteries, except for the occasional comfort read of a Dick Francis or Robert B. Parker. I read for work, of course; this is always rereading, which has its own challenges and rewards. This year I found myself wondering what my relationship will be to some of these books when I eventually retire. Will I stop rereading Jane Eyre or Bleak House or North and South? It is hard to imagine that I would never read Middlemarch again.

And on that faintly elegiac note I will add that I reread my year-end post from last year in which I talked about having to “downsize” my book collection when I moved, and it continues to be the case that my relationship to books has changed as a result. It’s not just that “my attachment to (most) books is just lighter” but that sometimes I stare at my shelves and wonder why I am hanging on to most of the books on them! I’m not about to live without any books, and it still means a lot to me to browse in them and remember reading them—or make plans to read them, as yes, I do have books that remain, shall we say, aspirational! (Hello, War and Peace.) The yellowing paperbacks of Elizabeth George mysteries, though, which my aging eyes tell me I will never read in those copies again? or even some of the newish books I was excited about and then kind of disappointed in? Why shouldn’t they go back into circulation, so that other readers can enjoy them (or be disappointed in them) in their turn? Also, speaking of eventually retiring, when that happens there are a lot of books now in my campus office that will come home with me. (Will I keep all of my different editions of Middlemarch? Maybe.)

And on that faintly elegiac note I will add that I reread my year-end post from last year in which I talked about having to “downsize” my book collection when I moved, and it continues to be the case that my relationship to books has changed as a result. It’s not just that “my attachment to (most) books is just lighter” but that sometimes I stare at my shelves and wonder why I am hanging on to most of the books on them! I’m not about to live without any books, and it still means a lot to me to browse in them and remember reading them—or make plans to read them, as yes, I do have books that remain, shall we say, aspirational! (Hello, War and Peace.) The yellowing paperbacks of Elizabeth George mysteries, though, which my aging eyes tell me I will never read in those copies again? or even some of the newish books I was excited about and then kind of disappointed in? Why shouldn’t they go back into circulation, so that other readers can enjoy them (or be disappointed in them) in their turn? Also, speaking of eventually retiring, when that happens there are a lot of books now in my campus office that will come home with me. (Will I keep all of my different editions of Middlemarch? Maybe.)

And that’s a wrap on another year of reading and blogging here at Novel Readings. Thanks to everyone who read and commented or chatted with me on Facebook or Instagram or Bluesky, and also to those who keep up their own blogs. I keep up with them via Feedly these days and I realize this has meant a decline in my own commenting. I am wary of making bold resolutions, so I won’t promise to do better in 2026, but I love reading your posts and I continue to cherish the online community we have sustained for so many years.

What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be  I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s

I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s  In my

In my  So I started 2024 by clearing out a lot of books. The other change since the separation has been to my reading time. I don’t quite understand why, but there seem to be a lot more hours in the day now that I live alone! I have wasted an awful lot of them watching TV, and many of them idly scrolling online, and plenty also just moping or mourning. I think (though this may be just making excuses) that I should not be too hard on myself about these bad habits, as the past few years have been pretty tough and we are all entitled to our coping strategies. I make intermittent resolutions to do better, to use my time better; I have made some of these for 2025. (Yes, blogging regularly again is one of them. We’ll see.) However! I have had more time for reading, and I have sometimes taken advantage of it. I have especially enjoyed taking time to read in the mornings. For many years—around two decades, really—mornings were my least favorite time of the day, what with all the kid stuff (breakfasts, lunches, getting dressed, remembering backpacks and permission slips and other forms, trying to get out the door on time) on top of bracing for my own work days, with the non-trivial (for me) anxiety of driving in winter weather adding a nice additional layer of stress from November through April. Things were simpler once the kids were older then out of the house, but I never felt like it was a good time for relaxing: I still had to get off to work, for one thing. Now, between habitually waking up early and living easy walking distance to work, even on weekdays I can afford to get in some peaceful reading while I have my tea and toast. We used to end most days in front of the TV; I still do that, especially on days when I’ve read a lot for work, but other days I can settle into my reading chair, put on some quiet music, and there’s nothing and nobody to interrupt me.

So I started 2024 by clearing out a lot of books. The other change since the separation has been to my reading time. I don’t quite understand why, but there seem to be a lot more hours in the day now that I live alone! I have wasted an awful lot of them watching TV, and many of them idly scrolling online, and plenty also just moping or mourning. I think (though this may be just making excuses) that I should not be too hard on myself about these bad habits, as the past few years have been pretty tough and we are all entitled to our coping strategies. I make intermittent resolutions to do better, to use my time better; I have made some of these for 2025. (Yes, blogging regularly again is one of them. We’ll see.) However! I have had more time for reading, and I have sometimes taken advantage of it. I have especially enjoyed taking time to read in the mornings. For many years—around two decades, really—mornings were my least favorite time of the day, what with all the kid stuff (breakfasts, lunches, getting dressed, remembering backpacks and permission slips and other forms, trying to get out the door on time) on top of bracing for my own work days, with the non-trivial (for me) anxiety of driving in winter weather adding a nice additional layer of stress from November through April. Things were simpler once the kids were older then out of the house, but I never felt like it was a good time for relaxing: I still had to get off to work, for one thing. Now, between habitually waking up early and living easy walking distance to work, even on weekdays I can afford to get in some peaceful reading while I have my tea and toast. We used to end most days in front of the TV; I still do that, especially on days when I’ve read a lot for work, but other days I can settle into my reading chair, put on some quiet music, and there’s nothing and nobody to interrupt me. The last two months of 2023 have been so frantic (about which more, perhaps, some other time) that not only did I get very little reading done that wasn’t absolutely necessary for work, but the chaotic atmosphere drove almost all recollection of what I’d read or written earlier in the year clear out of my mind. It’s a good thing I keep records! Looking them over, it was nice to be reminded of what was actually a pretty good year for both reading and writing. I’ll run through the highlights (and also some lowlights) here, as has been my year-end ritual since I started Novel Readings in 2007.

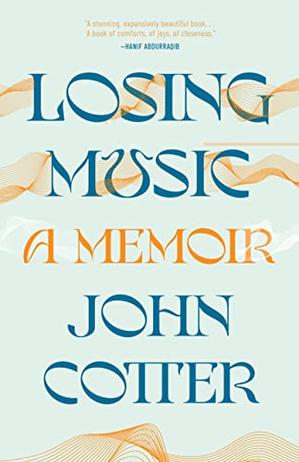

The last two months of 2023 have been so frantic (about which more, perhaps, some other time) that not only did I get very little reading done that wasn’t absolutely necessary for work, but the chaotic atmosphere drove almost all recollection of what I’d read or written earlier in the year clear out of my mind. It’s a good thing I keep records! Looking them over, it was nice to be reminded of what was actually a pretty good year for both reading and writing. I’ll run through the highlights (and also some lowlights) here, as has been my year-end ritual since I started Novel Readings in 2007. When I was asked by Trevor and Paul at the wonderful Mookse & Gripes podcast to contribute to their “best of the year” round-up episode, the book that immediately came to mind for me was John Cotter’s memoir Losing Music. It deserved but didn’t get a blog post of its own, but you can read a bit about it

When I was asked by Trevor and Paul at the wonderful Mookse & Gripes podcast to contribute to their “best of the year” round-up episode, the book that immediately came to mind for me was John Cotter’s memoir Losing Music. It deserved but didn’t get a blog post of its own, but you can read a bit about it  A stretch of uninspiring reading early in the year was broken by Jessica Au’s

A stretch of uninspiring reading early in the year was broken by Jessica Au’s  Barbara Kingsolver’s

Barbara Kingsolver’s  I can’t say reading

I can’t say reading  I wrote three reviews for the TLS in 2023, Toby Litt’s

I wrote three reviews for the TLS in 2023, Toby Litt’s  I wrote two other somewhat more academic pieces, though neither of them was, strictly speaking, a “research” publication. One was a review for Women’s Studies of Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby’s correspondence in an excellent new edition by Elaine and English Showalter; the other was an essay for a forum organized by my friend and (nearby) colleague Tom Ue on ‘teaching the Victorians’ today, which is coming out eventually in the Victorian Review. I have written literally thousands of words about how I teach the Victorians today: this was a task for which almost two decades of blogging was exactly the right preparation!

I wrote two other somewhat more academic pieces, though neither of them was, strictly speaking, a “research” publication. One was a review for Women’s Studies of Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby’s correspondence in an excellent new edition by Elaine and English Showalter; the other was an essay for a forum organized by my friend and (nearby) colleague Tom Ue on ‘teaching the Victorians’ today, which is coming out eventually in the Victorian Review. I have written literally thousands of words about how I teach the Victorians today: this was a task for which almost two decades of blogging was exactly the right preparation!

For some reason I had it in mind that 2019 had not been a very good reading year for me. Then I went back through my blog posts and discovered that, while there isn’t really one stand-out “best of the year” the way there sometimes is, there have been plenty of reading highlights, and hardly any outright duds. (That in itself is a good enough reason to keep blogging, if you ask me.) According to my book math, that means that overall 2019 has actually been a better than average reading year! Here’s a look back at some of its greatest hits, some also-rans, a few minor disappointments, and some failures (maybe mine, maybe the books’).

For some reason I had it in mind that 2019 had not been a very good reading year for me. Then I went back through my blog posts and discovered that, while there isn’t really one stand-out “best of the year” the way there sometimes is, there have been plenty of reading highlights, and hardly any outright duds. (That in itself is a good enough reason to keep blogging, if you ask me.) According to my book math, that means that overall 2019 has actually been a better than average reading year! Here’s a look back at some of its greatest hits, some also-rans, a few minor disappointments, and some failures (maybe mine, maybe the books’).

William Trevor’s

William Trevor’s  Sarah Hall’s

Sarah Hall’s  Reading

Reading  I found

I found

I really admired–and was ultimately quite moved by–the careful self-effacement of

I really admired–and was ultimately quite moved by–the careful self-effacement of  I had fun reading Anthony Horowitz’s

I had fun reading Anthony Horowitz’s  My review of Emma Donoghue’s Akin will be in Canadian Notes and Queries in the new year. I enjoyed reading it quite a bit: even though I found it somewhat contrived, Donoghue is a good enough storyteller to carry me along. It made me think, though, about why

My review of Emma Donoghue’s Akin will be in Canadian Notes and Queries in the new year. I enjoyed reading it quite a bit: even though I found it somewhat contrived, Donoghue is a good enough storyteller to carry me along. It made me think, though, about why  I absolutely love the idea of Persephone Books, and it is thrilling in principle to see so many publishers devoting themselves now to bringing back “lost classics.”

I absolutely love the idea of Persephone Books, and it is thrilling in principle to see so many publishers devoting themselves now to bringing back “lost classics.”

I am not a very good reader of Virginia Woolf’s fiction, and

I am not a very good reader of Virginia Woolf’s fiction, and

The End!

The End! I am trying not to feel dissatisfied with the writing I did in 2019. For one thing, I deliberately took a step back from a certain kind of ‘productivity’ in order to develop ideas about what I hope will turn into some worthwhile projects. This kind of

I am trying not to feel dissatisfied with the writing I did in 2019. For one thing, I deliberately took a step back from a certain kind of ‘productivity’ in order to develop ideas about what I hope will turn into some worthwhile projects. This kind of  In any case, as it turned out, all of my publications in 2019 were reviews. For Quill & Quire, I wrote about Antanas Sileika’s

In any case, as it turned out, all of my publications in 2019 were reviews. For Quill & Quire, I wrote about Antanas Sileika’s  This isn’t really a bad run of reading and writing: there wasn’t any point in 2019 when I didn’t have a review underway in addition to whatever other work I was doing. I think one reason I nonetheless feel disappointed about what I have to show for 2019 is that although many of these books engaged and interested me, none of them excited me the way that, for example,

This isn’t really a bad run of reading and writing: there wasn’t any point in 2019 when I didn’t have a review underway in addition to whatever other work I was doing. I think one reason I nonetheless feel disappointed about what I have to show for 2019 is that although many of these books engaged and interested me, none of them excited me the way that, for example,  I did publish one more substantial thing this year:

I did publish one more substantial thing this year:  It’s hard to know when to write these year-end posts: there’s always a chance that a book I read in the very final days of the year will be a real game changer! It’s a quiet snowy day today, though, perfect for a little blogging, so I’ll go ahead and write up my regular overview of highs and lows of my reading year and give any late entries their own posts.

It’s hard to know when to write these year-end posts: there’s always a chance that a book I read in the very final days of the year will be a real game changer! It’s a quiet snowy day today, though, perfect for a little blogging, so I’ll go ahead and write up my regular overview of highs and lows of my reading year and give any late entries their own posts.

I read quite a few books this year that I thought were near misses: good, even very good, but slightly dissatisfying, for one reason or another. Edna O’Brien’s

I read quite a few books this year that I thought were near misses: good, even very good, but slightly dissatisfying, for one reason or another. Edna O’Brien’s  I read a couple of critical darlings that did not quite work for me, though both Ali Smith’s

I read a couple of critical darlings that did not quite work for me, though both Ali Smith’s

I took

I took