I opened the book with some apprehension, wondering what archaic spelling and punctuation I would face. I found the expected f’s for s’s and a few other things that didn’t turn up as often, but I got used to them very quickly. And I began to get into Robinson Crusoe. As a kind of castaway myself, I was happy to escape into the fictional world of someone else’s trouble.

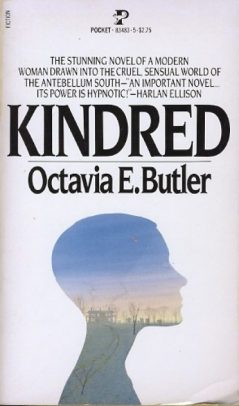

I read Kindred with unflagging attention: it is a gripping narrative, fast-moving and suspenseful and emotionally harrowing. It also, however, felt heavy-handed, almost didactic, and seemed formally and stylistically uninteresting. The time-traveling, which is never really explained or motivated–never given any autonomous logic–within the novel itself, functions as little more than a device to haul us back to to the antebellum South with Dana; its authorial objective is pretty clearly to teach us by immersion about the corrupting horrors of slavery. The back-and-forth in time also, of course, provides a neat mechanism for comparison: how much have things in fact changed; how deep-rooted and long-lasting are the effects of this traumatic past on the present; how, if at all, can a nation build a unified future on such a rotten foundation. It’s not that these aren’t interesting and important, even urgent, questions; I just didn’t find Butler’s literary treatment of them especially artful. Dana, too, seemed more a tool than a distinct character, though her relationship with Kevin, especially as his habits and attitudes are affected by his long stint away from their real (modern) life, seemed the most subtle and thought-provoking aspect of the novel.

Thinking more about Kindred after I’d finished reading it, I wondered if I would notice more subtleties in it if I knew more about the specific genres it combines: it is a hybrid of time-travel fiction and the slave narrative, and while I have read an example or two of each of these, I have never given sustained thought to their conventions and I have little, therefore, to compare Butler’s effects or choices to. The reader’s guide in my edition includes an essay by Robert Crossley that says some things about these contexts. “One of the protagonist’s–and Butler’s–achievements in traveling to the past,” he says, for instance,

Thinking more about Kindred after I’d finished reading it, I wondered if I would notice more subtleties in it if I knew more about the specific genres it combines: it is a hybrid of time-travel fiction and the slave narrative, and while I have read an example or two of each of these, I have never given sustained thought to their conventions and I have little, therefore, to compare Butler’s effects or choices to. The reader’s guide in my edition includes an essay by Robert Crossley that says some things about these contexts. “One of the protagonist’s–and Butler’s–achievements in traveling to the past,” he says, for instance,

is to see individual slaves as people rather than encrusted literary or sociological types. . . . Here we see literary fantasy in the service of the recovery of historical and psychological realities. As fictional memoir, Kindred is Butler’s contribution to the literature of memory every bit as much as it is an exercise in the fantastic imagination.

OK, I can see that, although there may be less novelty in that recovery effort now than there was in 1979–which of course does not diminish Butler’s contribution. He also remarks that “Science fiction and fantasy are a richly metaphorical literature,” but Kindred itself is not, as he tacitly acknowledges when he says that in it “the most powerful metaphor is time travel itself” but then explains that “metaphor” as “a dramatic means to make the past live”–which is not really metaphorical, is it? In fact, time travel aside, Kindred is an almost laboriously literal novel; sometimes the research behind it seemed to have been simply incorporated into Dana and Kevin’s conversations or into her narration. Not that anything’s wrong with that literal approach, and it delivers a lot of drama that is both heartrending and morally devastating, but the result is really just historical fiction with a twist.

The one big exception is the obviously symbolic loss of Dana’s arm, which, as Crossley says, Butler “makes no attempt to rationalize” but allows to stand as a shocking mystery: “the author is silent on the process by which Dana’s arm is severed in the twilight zone between past and present.” He goes on to quote Butler’s explanation of the figurative meaning of this amputation: “Antebellum slavery didn’t leave people quite whole.” That makes perfect sense, but I’m less satisfied than Crossley is with the inexplicable and arbitrary process by which her arm is lost, which is wholly unrelated to the way Dana has passed between the eras up to that point. It feels, again, like a device that gets the job done, rather than like the culmination of a meaningful pattern that would give the novel the kind of creative unity and flair that I felt the novel, for all its ingenuity and sincerity, was somehow missing.

I should add that I read Kindred (or read it right now, at any rate) because my book club chose it for our next meeting. As always, we are following a thread from our previous book, which in this case was Lincoln in the Bardo. Perhaps it is inevitable that the next book after Lincoln in the Bardo would seem somewhat pedestrian!