The books by George Meredith in fine bindings line shelves. In the cupboard in a velvet case lies a drawing from the hand of another young lover, of a beautiful, large-eyed woman smiling a little, demure in her bonnet. Perhaps the artist is saying something that causes her to forget, for a moment, some bitter things she has learned. His enamored pencil does not catch, perhaps, a certain fated expression in here eyes. Kisses, from whomever, have left no imprints on the pretty lips. The young lover sees only his own kisses there. She will die soon. He will grow old. All this is more than a hundred years ago now. “Earthly love speedily becomes unmindful but love from heaven is mindful for ever more,” it was to have said on her tombstone. No one knows where her grave is now.

The books by George Meredith in fine bindings line shelves. In the cupboard in a velvet case lies a drawing from the hand of another young lover, of a beautiful, large-eyed woman smiling a little, demure in her bonnet. Perhaps the artist is saying something that causes her to forget, for a moment, some bitter things she has learned. His enamored pencil does not catch, perhaps, a certain fated expression in here eyes. Kisses, from whomever, have left no imprints on the pretty lips. The young lover sees only his own kisses there. She will die soon. He will grow old. All this is more than a hundred years ago now. “Earthly love speedily becomes unmindful but love from heaven is mindful for ever more,” it was to have said on her tombstone. No one knows where her grave is now.

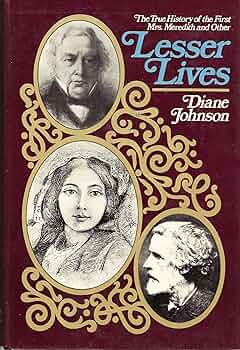

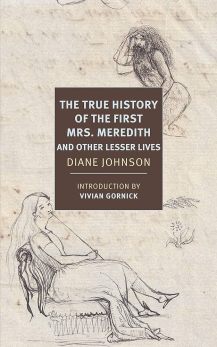

Reading Diane Johnson’s The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith (and Other Lesser Lives) is a disorienting experience. You think you know what you’re getting into when you begin—or I thought so, anyway. It is, after all, a period piece: first published in 1972, it is an exemplary contribution to the second-wave feminist project of literary reclamation, of resistance to the domination of men’s voices and men’s stories. Its tone, a blend of sass, defiance, and earnestness, reflects both the exuberance and the imperfections of that moment and that movement. Johnson’s project, in this context, initially sounds predictable, which is not to say it doesn’t also sound necessary and valuable, precisely as an act of resistance. “The life of Mary Ellen,” Johnson explains in her Preface,

is always treated, in a paragraph or a page, as an episode in the lives of [Thomas Love] Peacock or [George] Meredith. It was treated with a certain reserve in early biographies because it involves adultery and recrimination, and makes all the parties look ugly . . .

Mrs. Meredith’s life can be looked upon, of course, as an episode in the lives of Meredith or Peacock, but it cannot have seemed that way to her.

We are inundated today with stories of just such “lesser lives,” real and fictional, including novels about real but sidelined figures like The Paris Wife or ones like The Silence of the Girls that shift our point of view on “minor” characters in the great classical epics. When the subject is real person, the underlying point is always, as Johnson notes, that it is impossible, or should be, for someone not to be the main character in their own life. The ease with which, even today, we relegate women to secondary status, especially when they are connected in some way to—especially when they are wives of—“great men” continues to be shocking, or it should be. “Must it always be this way for women?” wonder the ghosts of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley early in Johnson’s book; “Here was one they thought might persevere in woman’s name. She had promise. She had courage.”

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says,

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says,

Mary Ellen, when she married George Meredith, had had a past already. Had already fallen in love, had already been married, had given birth to a child—all those life experiences that we normally expect to take place after the close of a Victorian novel, had taken place for Mary Ellen before the story with George began. The real drama of her life may have seemed to her to have nothing to do with George Meredith at all.

Every bit of information Johnson could scrounge up about Mary Ellen (including from a cache of letters she came across fortuitously in a box under a bed in a small house in Purley, Surrey) has gone into her recreation of that “real drama.” There is a lot of it! Mary Ellen’s father, the Romantic writer Thomas Love Peacock (he was a close friend of Shelley) thought girls should be free-spirited and educated and brought her up accordingly (he was in effect a single parent, as Mary Ellen’s mother “suffered from one of those long, household forms of madness, or severe neurosis, to which ladies in those days seemed especially prone). Peacock’s approach sounds delightful, and delightfully progressive:

Mary Ellen learned to read; she was allowed to read widely, pretty much what she wanted . . . unlike John Stuart [Mill], Mary Ellen was given fiction and poetry, to develop the heart as well as the head. And Mary Ellen messed around in boats, like a boy, and learned to row and sail and swim. She grew up to be a fearless horsewoman, so she was probably given a pony early.

And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.”

And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.”

The first “real drama” of Mary Ellen’s life was her first marriage, to a dashing sailor; he drowned, tragically, very soon after the wedding, but not too soon for Mary Ellen to have conceived a child. Then she met and married the aspiring novelist George Meredith, who was a few years her junior: apparently he always said she was 9 years older, but it was actually 6.5; he also called her “mad,” but in Johnson’s telling anyway, there is no supporting evidence for that claim. Things went well for the couple at first: they had literary ambition in common and eventually mutual projects, as well as children, but their happiness did not last. “The Historian cannot capture a process so slow as the death of a marriage,” Johnson (whose most famous novel today is called, as it happens, Le Divorce) remarks pensively:

He would need some other medium than the pen to do it with—perhaps one of those cameras that photograph the growing of a plant and the unfolding of its blossoms. With such a camera we could see the expressions change, telescoping the imperceptible changes of seven years into a few moments. We watch the passionate adoring glances glaze to cordiality, grow expressionless, contract with pain. The once ardent glances are now averted; fingers disentwine and are folded behind the separate backs. Backs are turned.

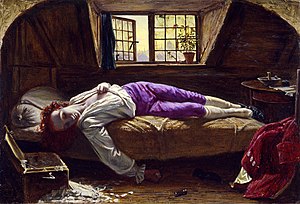

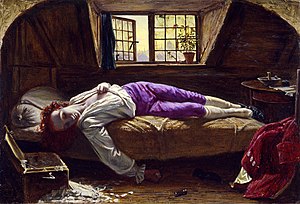

There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later ceramics collector—Henry Wallis. (Wallis’s most famous painting was and is ‘The Death of Chatterton,’ for which Meredith was the model.) They lived together adulterously and had a child; not long after, Mary Ellen died, leaving her still-doting father (and, presumably, her lover, but not her legal husband) bereft. Meredith continued to write novels; he also wrote a sonnet sequence, Modern Love, that chronicles the decay of a marriage much like his own. He achieved the lasting fame he always dreamed of and also made a second marriage with none of the turbulence of the first. Mary Ellen receded into obscurity, except, as Johnson emphasizes, through her pervasive presence in Meredith’s imagination and thus in his fiction.

There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later ceramics collector—Henry Wallis. (Wallis’s most famous painting was and is ‘The Death of Chatterton,’ for which Meredith was the model.) They lived together adulterously and had a child; not long after, Mary Ellen died, leaving her still-doting father (and, presumably, her lover, but not her legal husband) bereft. Meredith continued to write novels; he also wrote a sonnet sequence, Modern Love, that chronicles the decay of a marriage much like his own. He achieved the lasting fame he always dreamed of and also made a second marriage with none of the turbulence of the first. Mary Ellen receded into obscurity, except, as Johnson emphasizes, through her pervasive presence in Meredith’s imagination and thus in his fiction.

So far so good, and it is good, though there is possibly something reductive or dated in Johnson’s antagonistic vision of the times and people she writes about. It is hard to engage with the otherness of the past, especially when its values offend one’s own cherished principles; I struggle with this too, in my own thinking and writing and teaching about women in the 19th century, and I caution my students about it, urging them (for one thing) to avoid the anachronistic dichotomies often prompted by our ideas of what is or isn’t “feminist.” Johnson’s book, too, is now a historical document; that it sounds so “seventies” to me is not its fault, and it is overall a good thing that to some extent we can now take for granted the importance of “lesser lives” of all kinds, without insisting on it quite so, well, insistently.

The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write.

The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write.

She is also very interested in the reciprocal influence of genres on each other, especially of fictional conventions on the form of biographies, and of the impossibility in any case of simply recounting facts (even when there is abundant and unequivocal evidence of their outline, as there is not, for much of the story she is telling) without relying on qualities that are not strictly objective:

But what, anyway, are the ‘facts’ of a writer’s life? That George Meredith had an erring wife is a ‘fact,’ but for him, the existence of those fictional heroines Mrs. Mount and Mrs. Lovell is also ‘fact.’ The one is an external, the other an internal fact. The danger for the biographer, or critic, lies in mismatching external and interior equivalents. I suppose there is no safeguard against doing this except, one hopes, common sense and a (no doubt) suspect degree of empathy, especially with the ‘seamy’ side of human nature . . . Which returns me to my point: the biographer must be a historian, but also a novelist and a snoop.

At many points in The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith Johnson the novelist is clearly at work: she has to guess, imagine, speculate, embroider in order to fill in what we otherwise wouldn’t know. Does that mean that her biography (if that’s what it is) of Mary Ellen is not “true,” as the title proclaims it to be? Yes and no, I think she would readily say: it is as true as possible, factually, and where it cannot be true in that way, it is true to what her empathy reveals, or truthful about its status as empathetic guesswork.

The other aspect of The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith that I didn’t expect but really appreciated is pointed to by its subtitle, and Other Lesser Lives. More than just a memoir of Mary Ellen, Johnson’s book is a meditation on the whole concept of a “lesser life.” There is a polemical side to this, as I’ve already noted, a feminist advocacy for equalizing our attention, not looking only at, or caring only about, the great men of history:

Of course there is no way to really know the minds of Lizzie Rossetti, or the first Mrs. Milton, or all those silent Dickens children suffering the mad unkindness, the delirious pleasures of their terrifying father’s company . . . But we know a lesser life does not seem lesser to the person who leads one.

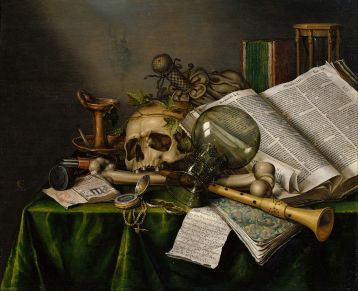

I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas,

I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas,

it is impossible to say. An old solicitor at the firm that always took care of Henry’s business remembers that he was a ‘tall thin man who always appeared to wear a long black cloak.’ Just before his twentieth birthday he entered the Bank of England and there worked with distinction, whatever working with distinction in a bank may involve [ha!], as Manager of the Dividend Department, for more than forty years and received a table service when he retired. He was happier than Papa, or Arthur [Mary Ellen’s son by George Meredith], or so it may be hoped, in that he married a pretty girl named Alice and had two children. Now they are all dead.

That’s an unexpected mic drop moment, there! It doesn’t mean (I feel certain) to suggest that none of what she’s just told us, or none of what these people did or were liked, matters, but it does abruptly remind us that in fact, all life stories end the same way. The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith ends on a similar note, more poignantly but still with a touch of the wit that makes the book such enjoyable reading:

Painters, writers, potters—all are dead. The greater lives along with the lesser. Things remain. Mary Ellen’s pink parasol lies in a trunk in a parlor in Purley [where Johnson found Mary Ellen’s letters]. Henry’s drawings lie in the boxroom upstairs. Henry’s little painting of George as Chatterton hangs in the Tate Gallery, properly humidified. The hair from Shelley’s head that Peacock gave to Henry, hair from the sacred hair of Shelley, Henry had put into a little ring, and people always kept it safe, but thieves broke into the house in Purley a year or two ago and stole it, and who can say where it is now? The turquoise vase from Rakka is safe in the museum; but I don’t know what happened to the majolica platter.

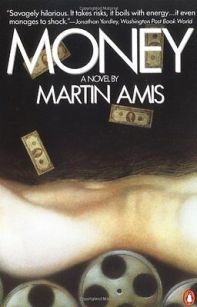

I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by the great discussion of it on Backlisted, which now I will listen to again.) It is that, but I was pleasantly surprised by how much more it is. I hope the others enjoy it as much as I did.

I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by the great discussion of it on Backlisted, which now I will listen to again.) It is that, but I was pleasantly surprised by how much more it is. I hope the others enjoy it as much as I did.

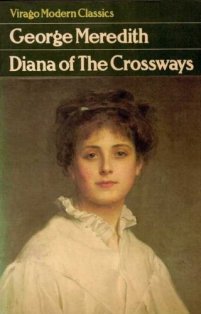

Now the pressing question is: do I want to read any of Meredith’s novels? or maybe Modern Love, which I read at least some of as a graduate student but haven’t looked at since? Before I read Johnson’s book, all that the name “George Meredith” readily brought to mind is Wilde’s famous quip “Meredith is a prose Browning, and so is Browning.” I love Browning, so maybe that’s a good omen? The Egoist seems to be generally considered Meredith’s best novel, but Johnson’s comments about Diana of the Crossways make it sound like the one I’d most like to try. Any Meredith lovers, or at least readers, out there who’d like to weigh in?

Another car would have come along, a family car for which she had said she was waiting, or even another man, a white man. Most travelers, like most men, were intrinsically decent. The end result for Iris would have been the same, cruelly the same. But he needn’t have been involved. He was the wrong man to have played Samaritan, and he’d known it, known it there on the road and in every irreversible moment since.

There are many interesting aspects of the investigation that unfolds as Hugh (with painful inevitability) ends up the prime suspect in Iris’s death. I haven’t spent enough time with the novel at this point to be sure what to make of all of them, but one thing I’ll want to think more about is Ellen’s role, which doesn’t fit any of the usual restrictive hard-boiled parts for women to play. It seems tied to the novel’s attention to class, which, as Mosley notes in his Afterword to the NYRB edition, does not protect Hugh the way he hopes it will: his education and career path, his family’s money and social standing—none of it insulates him from hatred or suspicion. But Ellen’s money and connections are sources of strength, as is her prompt and unequivocal commitment to being on Hugh’s side. If Iris can be seen as a version of the damsel-in-distress turned femme fatale (intentionally or not), Ellen is an ally and partner for Hugh, one who refuses to sit on the sidelines while an injustice is perpetrated. There are other details worth considering about who helps Hugh and who doesn’t, too, including the white lawyer whose motives are primarily political, rather than principled.

There are many interesting aspects of the investigation that unfolds as Hugh (with painful inevitability) ends up the prime suspect in Iris’s death. I haven’t spent enough time with the novel at this point to be sure what to make of all of them, but one thing I’ll want to think more about is Ellen’s role, which doesn’t fit any of the usual restrictive hard-boiled parts for women to play. It seems tied to the novel’s attention to class, which, as Mosley notes in his Afterword to the NYRB edition, does not protect Hugh the way he hopes it will: his education and career path, his family’s money and social standing—none of it insulates him from hatred or suspicion. But Ellen’s money and connections are sources of strength, as is her prompt and unequivocal commitment to being on Hugh’s side. If Iris can be seen as a version of the damsel-in-distress turned femme fatale (intentionally or not), Ellen is an ally and partner for Hugh, one who refuses to sit on the sidelines while an injustice is perpetrated. There are other details worth considering about who helps Hugh and who doesn’t, too, including the white lawyer whose motives are primarily political, rather than principled. The thing that does make me hesitate is the oddity (arguably) of assigning a novel that is fundamentally about race, and that is told from the point of view of a Black man—but which is written by a white woman. “A white woman writing of a young black man’s problems with the law was a certain kind of gamble,” Mosley comments in his Afterword—but Mosley himself doesn’t seem to consider it problematic, moving immediately on to remark Hughes’s general interest in writing “from perspectives far from her own.” It is clear from the afterword that Mosley greatly admires Hughes in general and The Expendable Man in particular. What kind of representation is more important, in a class like mine that tries to show the range of uses to which the forms of detective fiction have been put since its emergence as a distinct form? It seems as if Mosley would consider it most important to address “the darker reality” (as he puts it) that lies behind more “glittering versions of American life.” Presumably he thinks the gamble paid off for Hughes because the result was a very good novel.

The thing that does make me hesitate is the oddity (arguably) of assigning a novel that is fundamentally about race, and that is told from the point of view of a Black man—but which is written by a white woman. “A white woman writing of a young black man’s problems with the law was a certain kind of gamble,” Mosley comments in his Afterword—but Mosley himself doesn’t seem to consider it problematic, moving immediately on to remark Hughes’s general interest in writing “from perspectives far from her own.” It is clear from the afterword that Mosley greatly admires Hughes in general and The Expendable Man in particular. What kind of representation is more important, in a class like mine that tries to show the range of uses to which the forms of detective fiction have been put since its emergence as a distinct form? It seems as if Mosley would consider it most important to address “the darker reality” (as he puts it) that lies behind more “glittering versions of American life.” Presumably he thinks the gamble paid off for Hughes because the result was a very good novel. This term is the first one since I began posting about ‘this week in my classes’ in 2007 that I haven’t posted at all about my classes. What’s up with that, you might wonder? Well, more likely you hadn’t noticed or wondered, but I’ve certainly been aware of it and pondering what, if anything, to do about it.

This term is the first one since I began posting about ‘this week in my classes’ in 2007 that I haven’t posted at all about my classes. What’s up with that, you might wonder? Well, more likely you hadn’t noticed or wondered, but I’ve certainly been aware of it and pondering what, if anything, to do about it. It certainly isn’t anything to do with this term’s classes. At least from my perspective, both of them—Mystery & Detective Fiction and The Victorian ‘Woman Question’—have gone very well. Of course there have been the occasional sessions that dragged a bit, and we had an unusually high number of snow days that created a lot of logistical headaches, but in general discussion was both substantive and lively. I continue to try to wean myself from my lecture notes. This gets easier and easier in the mystery class, as I am pretty confident now both about how I want to frame the course and readings in terms of ‘big picture’ issues and about the specific readings. (I mix in new options quite regularly, because for various reasons I have been teaching the course basically every year for ages, so this definitely keeps it fresh and interesting for me: I just finished reading Dorothy B. Hughes’s The Expendable Man and I’m 90% certain I’m putting it on the reading list for next year, for one!) The ‘woman question’ class is a seminar, so I don’t lecture there anyway; I so looked forward to our class meetings all term, both because the readings are all favorites of mine and because we always had such good conversations about them. The only slight exception was with the excerpts from Aurora Leigh, from which I learned both that assigning excerpts is a bad idea (something I already believed but overrode, for practical reasons)—when it comes to long texts, do or do not, there is no try!—and that narrative poetry is hard, or at least it takes a different kind of preparation and attention than fiction, and that if I’m going to assign any of Aurora Leigh I need to take that into account.

It certainly isn’t anything to do with this term’s classes. At least from my perspective, both of them—Mystery & Detective Fiction and The Victorian ‘Woman Question’—have gone very well. Of course there have been the occasional sessions that dragged a bit, and we had an unusually high number of snow days that created a lot of logistical headaches, but in general discussion was both substantive and lively. I continue to try to wean myself from my lecture notes. This gets easier and easier in the mystery class, as I am pretty confident now both about how I want to frame the course and readings in terms of ‘big picture’ issues and about the specific readings. (I mix in new options quite regularly, because for various reasons I have been teaching the course basically every year for ages, so this definitely keeps it fresh and interesting for me: I just finished reading Dorothy B. Hughes’s The Expendable Man and I’m 90% certain I’m putting it on the reading list for next year, for one!) The ‘woman question’ class is a seminar, so I don’t lecture there anyway; I so looked forward to our class meetings all term, both because the readings are all favorites of mine and because we always had such good conversations about them. The only slight exception was with the excerpts from Aurora Leigh, from which I learned both that assigning excerpts is a bad idea (something I already believed but overrode, for practical reasons)—when it comes to long texts, do or do not, there is no try!—and that narrative poetry is hard, or at least it takes a different kind of preparation and attention than fiction, and that if I’m going to assign any of Aurora Leigh I need to take that into account. So what’s my problem this term? I think it is rooted in my uncertainty about how to address some big changes that have taken place in my personal life. When I wrote up my

So what’s my problem this term? I think it is rooted in my uncertainty about how to address some big changes that have taken place in my personal life. When I wrote up my  In my current circumstances, this principle, if that’s what it is, runs up against the principle that I shouldn’t talk about other people’s business here: it feels wrong not to acknowledge that my life has changed significantly, but I have felt—rightly, I think—constrained from going into any detail that might cross the line, which has also meant I have felt constrained from talking about some of my recent reading as frankly and completely as I would have liked to, because I couldn’t address how something like, say, Maggie Smith’s

In my current circumstances, this principle, if that’s what it is, runs up against the principle that I shouldn’t talk about other people’s business here: it feels wrong not to acknowledge that my life has changed significantly, but I have felt—rightly, I think—constrained from going into any detail that might cross the line, which has also meant I have felt constrained from talking about some of my recent reading as frankly and completely as I would have liked to, because I couldn’t address how something like, say, Maggie Smith’s  Obviously I have reached a point at which it seems fine and reasonable to say what has been going on, though I don’t expect I will ever consider Novel Readings an appropriate place to talk about how or why things have unfolded in this way, or even how I feel about it all! That’s nobody’s business but ours, by which I mean mine and my (truly excellent) therapist’s. 😉 Seriously, though, I do believe we bring our whole selves to our reading, so what I want to work on is how to acknowledge how my new reality sometimes does affect my engagement with books. I can say already that nothing about Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce, which I just read for my book club, seems relevant or resonant at all in that way (though I did enjoy it on its own terms)—though there were moments in

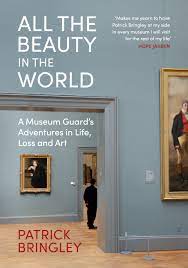

Obviously I have reached a point at which it seems fine and reasonable to say what has been going on, though I don’t expect I will ever consider Novel Readings an appropriate place to talk about how or why things have unfolded in this way, or even how I feel about it all! That’s nobody’s business but ours, by which I mean mine and my (truly excellent) therapist’s. 😉 Seriously, though, I do believe we bring our whole selves to our reading, so what I want to work on is how to acknowledge how my new reality sometimes does affect my engagement with books. I can say already that nothing about Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce, which I just read for my book club, seems relevant or resonant at all in that way (though I did enjoy it on its own terms)—though there were moments in  After college, for a period of two years and eight months, the “real world” became a room at Beth Israel Hospital and Tom’s one-bedroom apartment in Queens. Never mind that I was starting out at a glamorous job in a midtown skyscraper; it was these quieter spaces that taught me about beauty, grace, and loss—and, I suspected, about the meaning of art.

After college, for a period of two years and eight months, the “real world” became a room at Beth Israel Hospital and Tom’s one-bedroom apartment in Queens. Never mind that I was starting out at a glamorous job in a midtown skyscraper; it was these quieter spaces that taught me about beauty, grace, and loss—and, I suspected, about the meaning of art.

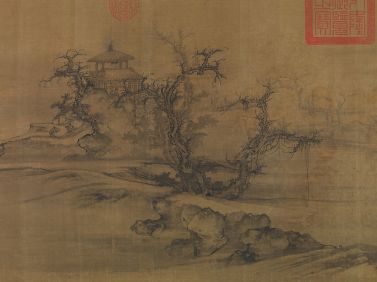

The individual sections of All the Beauty in the World are organized, more or less, around Bringley’s assignments to particular rooms or wings or exhibits; the larger framing is his gradual reconciliation, if that’s the right word, with the “real world” outside the museum as he learns to live with Tom’s loss. Both the people he works with (who come from all parts of the world and all have their own stories about how they came to be standing guard over Van Gogh’s Irises or the tomb of Perneb) and the people he encounters as visitors all play a part in this emotional journey, but it is the art that matters the most, in ways that are better suited to samples than summaries. Here, for instance, is Bringley’s description of a silk scroll hand-painted by Guo Xi, a “Northern Song Dynasty” master:

The individual sections of All the Beauty in the World are organized, more or less, around Bringley’s assignments to particular rooms or wings or exhibits; the larger framing is his gradual reconciliation, if that’s the right word, with the “real world” outside the museum as he learns to live with Tom’s loss. Both the people he works with (who come from all parts of the world and all have their own stories about how they came to be standing guard over Van Gogh’s Irises or the tomb of Perneb) and the people he encounters as visitors all play a part in this emotional journey, but it is the art that matters the most, in ways that are better suited to samples than summaries. Here, for instance, is Bringley’s description of a silk scroll hand-painted by Guo Xi, a “Northern Song Dynasty” master:

And so he leaves this job too. From now on when he returns to the museum it will be as a visitor, just another person stepping inside for a moment to be reminded of the obvious, and to be reassured

And so he leaves this job too. From now on when he returns to the museum it will be as a visitor, just another person stepping inside for a moment to be reminded of the obvious, and to be reassured Everything goes back to normal. Peter Manuel becomes a scary story people tell each other. Just a story. Just a creepy story about a serial killer.

Everything goes back to normal. Peter Manuel becomes a scary story people tell each other. Just a story. Just a creepy story about a serial killer.

One reason that to date I have not pursued this idea is that true crime, as a genre, makes me uneasy, squeamish, even—ethically, but also more literally. My experience with it is limited and mostly from television, where, for example, I have watched both the TV serial and the documentary The Staircase, as well as both The People vs O. J. Simpson and O. J.: Made in America — and also one season of Netflix’s Making a Murderer. If you can criticize made-up crime fiction for treating imaginary violent deaths as good subjects for an evening’s entertainment, how much worse is it to take the suffering and brutality and tragedy of actual murders and engage us with it in the spirit of a whodunit? Obviously, in both cases everything depends on the treatment: plenty of detective fiction does a lot more than offer us a puzzle, and I’m sure it is possible for true crime writing (or podcasting or dramatizations) to avoid the pitfalls of sensationalism, speculation, and grisly voyeurism. But it can’t help but be a grim kind of reading, writing, watching or thinking, and for my own forays into the already unhappy territory of murder I have just always relied, however naively, on the insulation that seemed to be provided, morally and imaginatively, by knowing that none of what I was reading about ever actually happened to anyone real.

One reason that to date I have not pursued this idea is that true crime, as a genre, makes me uneasy, squeamish, even—ethically, but also more literally. My experience with it is limited and mostly from television, where, for example, I have watched both the TV serial and the documentary The Staircase, as well as both The People vs O. J. Simpson and O. J.: Made in America — and also one season of Netflix’s Making a Murderer. If you can criticize made-up crime fiction for treating imaginary violent deaths as good subjects for an evening’s entertainment, how much worse is it to take the suffering and brutality and tragedy of actual murders and engage us with it in the spirit of a whodunit? Obviously, in both cases everything depends on the treatment: plenty of detective fiction does a lot more than offer us a puzzle, and I’m sure it is possible for true crime writing (or podcasting or dramatizations) to avoid the pitfalls of sensationalism, speculation, and grisly voyeurism. But it can’t help but be a grim kind of reading, writing, watching or thinking, and for my own forays into the already unhappy territory of murder I have just always relied, however naively, on the insulation that seemed to be provided, morally and imaginatively, by knowing that none of what I was reading about ever actually happened to anyone real.

Mina talks in the interview about people’s fascination with serial killers (a point that reminds me of another ‘true crime’ series I’ve seen, “Mindhunter”—which itself walks a fine line in its treatment of its subjects) and notes that people usually want to see them as anomalous. The version of Manuel that her book gives us is hardly “normal,” but at the same time there’s something small, petty, even pathetic about him, rather than monstrous. He represents himself at the trial and one factor in his favor, we’re told, is that

Mina talks in the interview about people’s fascination with serial killers (a point that reminds me of another ‘true crime’ series I’ve seen, “Mindhunter”—which itself walks a fine line in its treatment of its subjects) and notes that people usually want to see them as anomalous. The version of Manuel that her book gives us is hardly “normal,” but at the same time there’s something small, petty, even pathetic about him, rather than monstrous. He represents himself at the trial and one factor in his favor, we’re told, is that

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place.

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place. I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite:

I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite: I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer.

I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer. Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his

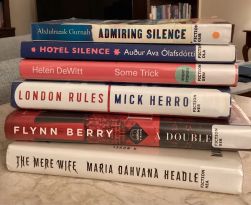

Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his  I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps

I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps

To anyone familiar with the rigid strictures women faced in the 19th-century, some aspects of Fayne will be predictable, even with the device of an intersex character to subvert the binaries they were based on. Fayne succeeds because MacDonald is a fine storyteller who has more to say than “the times were unfair to women,” or maybe more accurately more she wants to do than just offer this critique (which is not to say it’s not an important critique, or that through the character of Charles / Charlotte she doesn’t extend it significantly). Everything about Fayne suggests that MacDonald wants to have fun as a novelist by writing an unabashedly melodramatic novel with her own variations on the kinds of twists and surprises we get in Gothic or sensation fiction: mistaken or secret identities, false confinements, drugs, sexual secrets, lost heirs, treachery and deceptions of all kinds—but also true-hearted friends and allies pointing the way towards solutions to these mysteries and towards a future in which the people we come to care for will be safe and happy. Overall, it works! It is fun, gripping, surprising, infuriating, and often touching. And, not incidentally, Charlotte herself is a fine addition to the list of 19th-century literary heroines who put up lively resistance to oppressive norms: Jane Eyre, Maggie Tulliver, and Marion Halcombe, for starters. There are many moments in Fayne that are clearly nods to Charlotte’s rebellious predecessors.

To anyone familiar with the rigid strictures women faced in the 19th-century, some aspects of Fayne will be predictable, even with the device of an intersex character to subvert the binaries they were based on. Fayne succeeds because MacDonald is a fine storyteller who has more to say than “the times were unfair to women,” or maybe more accurately more she wants to do than just offer this critique (which is not to say it’s not an important critique, or that through the character of Charles / Charlotte she doesn’t extend it significantly). Everything about Fayne suggests that MacDonald wants to have fun as a novelist by writing an unabashedly melodramatic novel with her own variations on the kinds of twists and surprises we get in Gothic or sensation fiction: mistaken or secret identities, false confinements, drugs, sexual secrets, lost heirs, treachery and deceptions of all kinds—but also true-hearted friends and allies pointing the way towards solutions to these mysteries and towards a future in which the people we come to care for will be safe and happy. Overall, it works! It is fun, gripping, surprising, infuriating, and often touching. And, not incidentally, Charlotte herself is a fine addition to the list of 19th-century literary heroines who put up lively resistance to oppressive norms: Jane Eyre, Maggie Tulliver, and Marion Halcombe, for starters. There are many moments in Fayne that are clearly nods to Charlotte’s rebellious predecessors.

Orbital does more, though, than indulge in this potentially saccharine vision of a perfect world spoiled, pointlessly, by human squabbles, greed, and violence. This is a common starting point, the novel proposes, including for the astronauts, initially overwhelmed by the invisibility of the borders and boundaries that motivate so much hostility and cause so much death:

Orbital does more, though, than indulge in this potentially saccharine vision of a perfect world spoiled, pointlessly, by human squabbles, greed, and violence. This is a common starting point, the novel proposes, including for the astronauts, initially overwhelmed by the invisibility of the borders and boundaries that motivate so much hostility and cause so much death: The astronauts are also aware that their own astonishing vantage point is itself implicated in these forces; running through the novel is a debate, unsettled (perhaps impossible to settle), about the value of space exploration, about ideas of progress and the capacity of human invention to do as much harm as good. One of the astronauts, Chie, reflects on her own family history, including the accidents of circumstance that meant her grandfather and her mother survived the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. What story did her mother intend Chie to discern in the photograph she has given her labelled “Moon Landing Day”?

The astronauts are also aware that their own astonishing vantage point is itself implicated in these forces; running through the novel is a debate, unsettled (perhaps impossible to settle), about the value of space exploration, about ideas of progress and the capacity of human invention to do as much harm as good. One of the astronauts, Chie, reflects on her own family history, including the accidents of circumstance that meant her grandfather and her mother survived the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. What story did her mother intend Chie to discern in the photograph she has given her labelled “Moon Landing Day”? The last two months of 2023 have been so frantic (about which more, perhaps, some other time) that not only did I get very little reading done that wasn’t absolutely necessary for work, but the chaotic atmosphere drove almost all recollection of what I’d read or written earlier in the year clear out of my mind. It’s a good thing I keep records! Looking them over, it was nice to be reminded of what was actually a pretty good year for both reading and writing. I’ll run through the highlights (and also some lowlights) here, as has been my year-end ritual since I started Novel Readings in 2007.

The last two months of 2023 have been so frantic (about which more, perhaps, some other time) that not only did I get very little reading done that wasn’t absolutely necessary for work, but the chaotic atmosphere drove almost all recollection of what I’d read or written earlier in the year clear out of my mind. It’s a good thing I keep records! Looking them over, it was nice to be reminded of what was actually a pretty good year for both reading and writing. I’ll run through the highlights (and also some lowlights) here, as has been my year-end ritual since I started Novel Readings in 2007. When I was asked by Trevor and Paul at the wonderful Mookse & Gripes podcast to contribute to their “best of the year” round-up episode, the book that immediately came to mind for me was John Cotter’s memoir Losing Music. It deserved but didn’t get a blog post of its own, but you can read a bit about it

When I was asked by Trevor and Paul at the wonderful Mookse & Gripes podcast to contribute to their “best of the year” round-up episode, the book that immediately came to mind for me was John Cotter’s memoir Losing Music. It deserved but didn’t get a blog post of its own, but you can read a bit about it  A stretch of uninspiring reading early in the year was broken by Jessica Au’s

A stretch of uninspiring reading early in the year was broken by Jessica Au’s  Barbara Kingsolver’s

Barbara Kingsolver’s  I can’t say reading

I can’t say reading  I wrote three reviews for the TLS in 2023, Toby Litt’s

I wrote three reviews for the TLS in 2023, Toby Litt’s  I wrote two other somewhat more academic pieces, though neither of them was, strictly speaking, a “research” publication. One was a review for Women’s Studies of Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby’s correspondence in an excellent new edition by Elaine and English Showalter; the other was an essay for a forum organized by my friend and (nearby) colleague Tom Ue on ‘teaching the Victorians’ today, which is coming out eventually in the Victorian Review. I have written literally thousands of words about how I teach the Victorians today: this was a task for which almost two decades of blogging was exactly the right preparation!

I wrote two other somewhat more academic pieces, though neither of them was, strictly speaking, a “research” publication. One was a review for Women’s Studies of Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby’s correspondence in an excellent new edition by Elaine and English Showalter; the other was an essay for a forum organized by my friend and (nearby) colleague Tom Ue on ‘teaching the Victorians’ today, which is coming out eventually in the Victorian Review. I have written literally thousands of words about how I teach the Victorians today: this was a task for which almost two decades of blogging was exactly the right preparation!

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says,

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says, And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.”

And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.” There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later

There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later  The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write.

The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write. I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas,

I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas, I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by

I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by  Money, money, money,

Money, money, money, But it matters (to me, at least) what those sentences are about, and also what they are for, and for me and most of the others in my book club, this was really the sticking point. What is it exactly that we are being invited to participate in when we read this novel? How far does “it’s for comic effect” excuse offering up the things Self says and does for our (presumed) entertainment? What kind of implied author (to let Amis himself temporarily off the hook) thinks that we will laugh, not just at how stupid Self is at the opera but at his attempts at rape? that we will be engaged and rewarded by a monologue that (however energetic and rhetorically ingenious) is relentlessly sexist and racist and bigoted? Again, we get it: John Self is an anti-hero, mercilessly exposed in all his vices; the novel is satirical, Rabelaisian, Swiftian, pick your poison. It is poisonous stuff, though, and—to bring Amis back into it—there’s such a sense of gleeful bad boy “look at me” about the whole thing, with all the metafictional cleverness deployed as back-up in case the whole “I’m only joking” excuse isn’t enough. That it is such a popular book among (as far we could tell, only) male readers is disconcerting: it’s as if an uncomfortable number of them enjoy a chance to vicariously indulge the kinds of demeaning, exploitative, offensive attitudes (towards women especially) that they know better than to express in propria persona. As we discussed, we have all had the tediously unpleasant experience, at one point of another, of calling out sexism in conversation with men we know, or in TV or movies we are watching with them, only to be dismissed or shut down or worse—often, again, with “it’s only a joke.” The feminist kill-joy is a role we’d rather not have to play, but the alternative is to shut up and take it. Between us, too, we’ve had enough of the other kinds of bad experiences John Self inflicts on the women in his life not to find his shamelessness about them entertaining. We don’t need any lessons in how bad this kind of s–t is, after all, so what social or moral or other revelation can possibly come our way from approaching them by way of John Self?

But it matters (to me, at least) what those sentences are about, and also what they are for, and for me and most of the others in my book club, this was really the sticking point. What is it exactly that we are being invited to participate in when we read this novel? How far does “it’s for comic effect” excuse offering up the things Self says and does for our (presumed) entertainment? What kind of implied author (to let Amis himself temporarily off the hook) thinks that we will laugh, not just at how stupid Self is at the opera but at his attempts at rape? that we will be engaged and rewarded by a monologue that (however energetic and rhetorically ingenious) is relentlessly sexist and racist and bigoted? Again, we get it: John Self is an anti-hero, mercilessly exposed in all his vices; the novel is satirical, Rabelaisian, Swiftian, pick your poison. It is poisonous stuff, though, and—to bring Amis back into it—there’s such a sense of gleeful bad boy “look at me” about the whole thing, with all the metafictional cleverness deployed as back-up in case the whole “I’m only joking” excuse isn’t enough. That it is such a popular book among (as far we could tell, only) male readers is disconcerting: it’s as if an uncomfortable number of them enjoy a chance to vicariously indulge the kinds of demeaning, exploitative, offensive attitudes (towards women especially) that they know better than to express in propria persona. As we discussed, we have all had the tediously unpleasant experience, at one point of another, of calling out sexism in conversation with men we know, or in TV or movies we are watching with them, only to be dismissed or shut down or worse—often, again, with “it’s only a joke.” The feminist kill-joy is a role we’d rather not have to play, but the alternative is to shut up and take it. Between us, too, we’ve had enough of the other kinds of bad experiences John Self inflicts on the women in his life not to find his shamelessness about them entertaining. We don’t need any lessons in how bad this kind of s–t is, after all, so what social or moral or other revelation can possibly come our way from approaching them by way of John Self? Our discussion wasn’t all negative. One member of the group noted that she felt John Self was a genuinely memorable, even iconic character, and we all grudgingly agreed that, hate him though we did, he was brilliantly executed: his voice (which is what Amis identified as the most important aspect of the novel, and fair enough) is distinctive and unforgettable. That we would like to forget it could, I suppose, be considered our problem, not the novel’s! Money also prompted a lot of discussion about the more general question of how far a novelist can or should go with an offensive character; we also considered why or whether Self is really so much worse than, say, the soulless ensemble of characters in Succession. We thought that Money would not have worked at all from the outside: what interest we took in Self, and any glimmering of sympathy we had for him, was entirely a product of our immersion in his point of view, which in turn became a test for us of Amis’s experiment, of how far he could go without losing us. We did all read to the end (though we mostly admitted having done some strategic skimming when it just got to be too much)—and our conversation was definitely lively. I don’t expect any of us will read anything else by Amis, though. (Years ago, I remembered, we read his father’s Ending Up, which we enjoyed thoroughly.)

Our discussion wasn’t all negative. One member of the group noted that she felt John Self was a genuinely memorable, even iconic character, and we all grudgingly agreed that, hate him though we did, he was brilliantly executed: his voice (which is what Amis identified as the most important aspect of the novel, and fair enough) is distinctive and unforgettable. That we would like to forget it could, I suppose, be considered our problem, not the novel’s! Money also prompted a lot of discussion about the more general question of how far a novelist can or should go with an offensive character; we also considered why or whether Self is really so much worse than, say, the soulless ensemble of characters in Succession. We thought that Money would not have worked at all from the outside: what interest we took in Self, and any glimmering of sympathy we had for him, was entirely a product of our immersion in his point of view, which in turn became a test for us of Amis’s experiment, of how far he could go without losing us. We did all read to the end (though we mostly admitted having done some strategic skimming when it just got to be too much)—and our conversation was definitely lively. I don’t expect any of us will read anything else by Amis, though. (Years ago, I remembered, we read his father’s Ending Up, which we enjoyed thoroughly.)