The driveway wasn’t as long as I remembered but the house seemed exactly the same: sunlit, flower-decked, gleaming. I had known since my earliest days at Choate that the world was full of bigger houses, grander and more ridiculous houses, but none were so beautiful. There was the familiar crunch of pea gravel beneath the tires, and when she stopped the car in front of the stone steps I could imagine how elated my father must have felt, and how my sister must have wanted to run off in the grass, and how my mother, alone, had stared up at so much glass and wondered what this fantastical museum was doing in the countryside.

I really enjoyed reading The Dutch House. Its brisk intensity kept me turning pages more quickly than the modest scale of action in the novel quite justified; its main characters, siblings Danny and Maeve Conroy, are convincing creations, both, in their own ways, quietly forceful; the ‘family saga’ elements had an understated fairy-tale quality to them–absent mother, wicked step-mother, loss and recreation of fortune, all perfectly plausible but also just a bit too pat, as if they were all part realism, part magic trick, the kind all novelists rely on but done overtly, with a bit of a flourish.

At the same time, the novel made no sense to me at all, or at least its ostensible central premise did not. It’s not just that the Dutch House is too good to be true, with its elaborate moldings and frescoed ceilings and luxurious decor, but that it seems to have far more agency in the plot than a building should: it figures too largely in everyone’s decisions, loves, hatreds, and grievances.

Something about it, and thus about the novel, fell into place for me near the end, though, when Danny and Maeve return to the Dutch House decades after their step-mother ruthlessly evicted them. “The house looked the same as it did when we walked out thirty years before,” Danny says wonderingly:

Maybe a few pieces of furniture had been rearranged, reupholstered, replaced, who could remember? There were the silk drapes, the yellow silk chairs, the Dutch books still in the glass-fronted secretary reaching up and up towards the ceiling, forever unread. Even the silver cigarette boxes were there, polished and waiting on the end tables, just as they had been when the VanHoebeeks walked the earth . . .

Maeve and my mother floated into the room in silence, both of them looking at things they had never planned on seeing again: the tapestry ottoman, the Chinese lamp, the heavy tasseled ropes of twisted silk, blue and green, that held the draperies back.

The emphasis on the house’s stasis tripped me up: in thirty years, things must, surely, have been rearranged, reupholstered, replaced. If it’s a house, not just a literary device, then it should have changed over time, reflecting the lives lived in it and the wider life outside of it. Danny and Maeve have certainly changed, even finally giving up their frequent trips to stare at their former home with a potent mixture of nostalgia and resentment about their disinheritance. This visit should figure–and in fact it does–as a chance to measure that change and to put their memories of the Dutch House into perspective.

The emphasis on the house’s stasis tripped me up: in thirty years, things must, surely, have been rearranged, reupholstered, replaced. If it’s a house, not just a literary device, then it should have changed over time, reflecting the lives lived in it and the wider life outside of it. Danny and Maeve have certainly changed, even finally giving up their frequent trips to stare at their former home with a potent mixture of nostalgia and resentment about their disinheritance. This visit should figure–and in fact it does–as a chance to measure that change and to put their memories of the Dutch House into perspective.

The house works fine in this way, but the odd quality it has throughout the novel and especially in this scene made me ask myself whether it was ever supposed to be a real house at all. I don’t mean whether Patchett based in on an actual house, but whether in the novel it really does work primarily, maybe even exclusively, as a metaphor. What Maeve and Danny are really contemplating when they park across the street from it all those times is their past, their family, their story, and in a way, isn’t that what we all do when we return, mentally or literally, to the places we used to live and the people we used to be? The particulars of the Conroys’ story are well detailed–Patchett is always a good storyteller–but in the end The Dutch House makes most sense to me not as a story about them but as a cautionary tale about how much we define ourselves by our pasts and how far, as a result, our lives are either limited or liberated by the space we imagine them in.

I realize that this is a perfectly obvious reading of The Dutch House: I’m sure I’m not the only reader to fixate on the house itself as symbol rather than setting. Perhaps reading it near Christmas is what made me feel that backwards pull so strongly–at this time of year especially I recognize in myself a similar temptation to dwell in (or on) a childhood space that may have been imperfect but in retrospect seems so certain, so much a part of my current identity even though it is no longer the setting for my life. Because Danny and Maeve are shunted unceremoniously out of their home, the abrupt transition makes it particularly hard for them to move on. Even as they make new homes and family ties they seem somehow stunted or unfinished as adults, while they keep going back and back again to brood about a place where they no longer belong.

I realize that this is a perfectly obvious reading of The Dutch House: I’m sure I’m not the only reader to fixate on the house itself as symbol rather than setting. Perhaps reading it near Christmas is what made me feel that backwards pull so strongly–at this time of year especially I recognize in myself a similar temptation to dwell in (or on) a childhood space that may have been imperfect but in retrospect seems so certain, so much a part of my current identity even though it is no longer the setting for my life. Because Danny and Maeve are shunted unceremoniously out of their home, the abrupt transition makes it particularly hard for them to move on. Even as they make new homes and family ties they seem somehow stunted or unfinished as adults, while they keep going back and back again to brood about a place where they no longer belong.

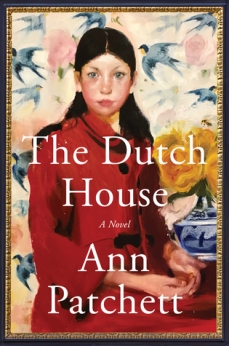

Yet it’s their long-deferred return to the Dutch House itself that allows them, finally, to make it part of their present instead of an imposing embodiment of their thwarted past. On this visit they retrieve the portrait of Maeve that has stayed through the years, “hanging exactly where it always had been”:

Maeve was ten years old, her shining black hair down past the shoulders of her red coat, the wallpaper from the observatory behind her, graceful imaginary swallows flying past pink roses, Maeve’s blue eyes dark and bright. Anyone looking at that painting would have wondered what had become of her. She was a magnificent child, and the whole world was laid out in front her her, covered in stars.

The portrait, belatedly detached from the Dutch House, becomes its own symbol of forward-looking continuity, in contrast to the static relics that the portraits of the house’s former owners, the VanHoebeks, have always been. Lives should be movement and change, not museums, seems to be the novel’s idea–or one of its ideas, anyway. It’s not just that houses get new owners, but that we all need to work on living as best we can wherever we are.

Images: John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Elsie Palmer (1890) ; Edward Hopper, House by the Railroad (1925)

Interesting. In my review (Sept. 2, 2019) I said “Taking the house as a metaphor for the lives of many people Patchett’s age (and mine) on this splendid planet could be interesting, but the story line is very literal.” But I can see that reading it this near to the holidays might give it extra metaphorical resonance.

LikeLike

Thank you for reminding me of your review. I like your point about the gender roles: I puzzled a bit over Maeve in that respect, as she so consistently rebuffs Danny’s attempts (once he’s fully launched) to change her life, which she seems to like even though to him (and mostly to me) it seems a very dull one for someone with her fierceness.

LikeLike

I haven’t read the book yet, but Patchett can be tricky, as she was in “State of Wonder” with its almost-real reimagining of “Heart of Darkness.” But your description immediately made me jump to Miss Havisham’s Satis House in “Great Expectations,” where the house and its unmoving contents do the same thing you imagine might be happening here. Patchett is clearly accomplished enough to touch a note from a great novel of the past. And, is the house as the characters see it, or are they willing it to be that way? Your thoughts have made me want to put this book much higher on my TBR shelf.

LikeLike

Interesting suggestions, Christopher. My own reading did not suggest Satis House as a model or an allusion, but I think it is true that the house is as the characters see it, which is one reason I ended up liking it best as “just” a metaphor rather than a realistic depiction of a place they lived.

LikeLike

Reading these reviews, I realize the true brilliance of Patchett, that her book is just as true in its humanity as it is in its symbolism. I did not consider the house to have any significance beyond metaphor, but reading the previous reviews, I can see that the sentimentality and longing for home resonated with many readers.

I felt I had a very clear understanding of the house as a symbol only based on a few areas.

It is foremost a symbol of excessive wealth and the illness of societies arranged and oriented around wealth-

When Cyril carries Maeve’s bag up to the third floor she feels this as a banishment, though the third floor is meant to be the highest status in the house at the time of its construction. Climbing the stairs makes Cyril’s knee (an injury of WWII) hurt so badly he cannot climb back down stairs for sometime.

It is no accident that the construction and change in ownership of the house, as well as the accumulation of wealth in the novel take place adjacent to the three most memorable wars in our country’s history. These were moments where huge disparities opened and widened in the US.

First, the VanHoebek’s made their fortune manufacturing cigarettes, giving them to soldiers as comfort overseas who then came home with the habit. The novel then makes reference throughout to patients with lung cancer, emphysema, and new wings “metastasizing” off of hospitals. Of course they are the ultimate symbols of immoral profit seeking behavior. The VanHoebeks of course constructed the home. And their intention was to own everything under the sky with no neighbors in sight.

Then we have WWII, the beginning of the military industrial complex. When Cyril comes home he purchased land that is quickly sold to the the military, after which, he can now takes up residence in the Dutch House as the new agent of power and wealth.

All the while, Elna, the devout catholic mother despises the house so much it makes her ill so that she must periodically return to the convent for rest.

The mention and timing of Catholic holidays is also essential to understanding the role of the house. There are several occasions when the family is absent from the home during Maundy Thursday, with the expectation of returning to the home on Easter. Well this of course means that the catholic members of the family are never present in the house during lent, which is the return to poverty through intentional fasting.

The virtue of poverty is then driven home when Danny and Maeve watch a production of the nutcracker. Danny is fixated on the mice, who of course symbolize the socialists who threatened the Russian Monarchy. Danny even says that the set of the nutcracker looks like the Dutch House even with the portraits that hang in the living room. Well those portraits in the Nutcracker would symbolize the legitimacy of rule by the lineage of the rulers.

Furthermore, Maeve is made sick watching the play in which the monarchy prevails and the rat king, the symbol of collective uprising is killed by the Nutcracker.

Of course Maeve, named for the Irish goddess of destruction, cannot Physically tolerate such injustice.

So, I saw the house as a symbol for the antiquated, yet all the while consuming and oppressive organization of our wealth obsessed society.

LikeLike

Thank you for adding these very interesting observations, Kristine!

LikeLike