He breathes in. He breathes out. He turns his head and breathes into the whorls of her ear; he breathes in his strength, his health, his all. You will stay, is what he whispers, and I will go. He sends these words into her: I want you to take my life. It shall be yours. I give it to you.

They cannot both live: he sees this and she sees this. There is not enough life, enough air, enough blood for both of them. Perhaps there never was. And if either of them is to live, it must be her. He wills it. He grips the sheet, tight, in both hands. He, Hamnet, decrees it. It shall be.

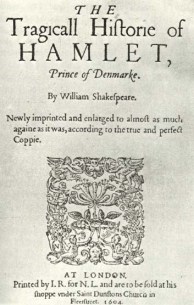

Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet and Judith began with a fragment, a scrap, of knowledge, about “a boy who died in Stratford, Warwickshire, in the summer of 1596,” a boy named Hamnet whose father, just a few years later, wrote a play called Hamlet. The names are the same, “entirely interchangeable,” according to Stephen Greenblatt, whose essay “The death of Hamnet and the making of Hamlet” provides one of O’Farrell’s epigraphs. In her author’s note, O’Farrell explains just how little we know about the real Hamnet, and also tells us that the central event of her novel, Hamnet’s sudden death from the bubonic plague, is a fiction: “it is not known why Hamnet Shakespeare died.” From this slight material O’Farrell develops a novel that is a delicate combination of historical recreation and literary excavation, of intimately portrayed human lives and undercurrents of meaning that flow almost unnoticed towards Shakespeare’s tragic drama.

It is impossible not to have Hamlet in mind while reading Hamnet (as it is more simply and, I think, more aptly titled in its UK release), and I imagine that someone who knows the play better than I do (so, a lot of people!) would find many echoes and resonances that deepen O’Farrell’s effects. But she resists, rightly I think, making either Shakespeare or Hamlet the most important thing about Hamnet–she avoids holding out their future fame (unknown and unforeseeable to her characters, after all) as what matters most about the lives her people are living in the moment. Instead, she focuses our attention and ties our emotions to their small family circle, and especially to the story of Hamnet’s mother Agnes (better known to us as Anne). The novel’s themes of love and loss, grief and guilt, parents and children, are (some of) Hamlet‘s themes as well, and by the end O’Farrell has convinced me of their connection, but in her telling Hamnet’s death does not matter because it inspired Hamlet, but rather Hamlet matters because it is an offering to Hamnet:

It is impossible not to have Hamlet in mind while reading Hamnet (as it is more simply and, I think, more aptly titled in its UK release), and I imagine that someone who knows the play better than I do (so, a lot of people!) would find many echoes and resonances that deepen O’Farrell’s effects. But she resists, rightly I think, making either Shakespeare or Hamlet the most important thing about Hamnet–she avoids holding out their future fame (unknown and unforeseeable to her characters, after all) as what matters most about the lives her people are living in the moment. Instead, she focuses our attention and ties our emotions to their small family circle, and especially to the story of Hamnet’s mother Agnes (better known to us as Anne). The novel’s themes of love and loss, grief and guilt, parents and children, are (some of) Hamlet‘s themes as well, and by the end O’Farrell has convinced me of their connection, but in her telling Hamnet’s death does not matter because it inspired Hamlet, but rather Hamlet matters because it is an offering to Hamnet:

Her husband has brought him back to life, in the only way he can. . . . He has taken his son’s death and made it his own; he has put himself in death’s clutches, resurrecting the boy in his place.

That seems, perhaps, like a subtle difference, but it is an inversion of priorities that I think reflects O’Farrell’s determination to subvert expectations for a novel “about” Shakespeare, to refuse the “great man” model of history and literature that made Sandra Newman’s The Heavens dissatisfying. (I think Newman too aimed to reject or ironize this model, but I found O’Farrell’s approach, though superficially more conventional, ultimately more effective at unsettling it.)

Shakespeare’s greatness, as Agnes understands it, is as a father, not as a playwright. In fact, Shakespeare (who is never directly named–he is always “the glover’s son” or “the Latin tutor” or just the husband or the father) is just barely a main character in O’Farrell’s novel. Hamnet is really Agnes’s book, and O’Farrell portrays her with wonderful specificity, from her knowledge of medicinal herbs to her uncanny ability to read a person’s character and future from pinching the bit of flesh between thumb and forefinger:

Shakespeare’s greatness, as Agnes understands it, is as a father, not as a playwright. In fact, Shakespeare (who is never directly named–he is always “the glover’s son” or “the Latin tutor” or just the husband or the father) is just barely a main character in O’Farrell’s novel. Hamnet is really Agnes’s book, and O’Farrell portrays her with wonderful specificity, from her knowledge of medicinal herbs to her uncanny ability to read a person’s character and future from pinching the bit of flesh between thumb and forefinger:

A person’s ability, their reach, their essence can be gleaned. All that they have held, kept, and all they long to grip is there in that place. It is possible, she realises, to find out everything you need to know about a person just by pressing it.

When she first takes the Latin tutor’s hand, she feels something different, “something she would never have expected to find in the hand of a clean-booted grammar-school boy from town”:

It was far-reaching: this much she knew. It had layers and strata, like a landscape. There were spaces and vacancies, dense patches, underground caves, rises and descents. There wasn’t enough time for her to get a sense of it all — it was too big, too complex. It eluded her, mostly. She knew there was more of it than she could grasp, that it was bigger than both of them.

Her understanding that there is more to this young man than his current circumstances can accommodate becomes part of the story of their married life, as she prompts him to leave their household in Stratford and make his way to London.

It’s there, of course, that he finds his vocation and begins the work that will lead him to Hamlet and beyond. But that richer life keeps him apart from Agnes and his children: his older daughter Susanna and the twins, Hamnet and Judith. He is away on the day Judith becomes ill, which turns into the day Hamnet dies. Agnes too is away, though not as distant, and O’Farrell writes with devastating clarity about what it means to her when she discovers that her harmless expedition to gather honey meant that her son faced catastrophe alone:

It’s there, of course, that he finds his vocation and begins the work that will lead him to Hamlet and beyond. But that richer life keeps him apart from Agnes and his children: his older daughter Susanna and the twins, Hamnet and Judith. He is away on the day Judith becomes ill, which turns into the day Hamnet dies. Agnes too is away, though not as distant, and O’Farrell writes with devastating clarity about what it means to her when she discovers that her harmless expedition to gather honey meant that her son faced catastrophe alone:

Every life has its kernel, its hub, its epicentre, from which everything flows out, to which everything returns. This moment is the absent mother’s: the boy, the empty house, the deserted yard, the unheard cry. Him standing there, at the back of the house, calling for the people who had fed him, swaddled him, rocked him to sleep, held his hand as he took his first steps, taught him to use a spoon, to blow on broth before he ate it, to take care crossing the street, to let sleeping dogs lie, to swill out of a cup before drinking, to stay away from deep water.

It will lie at her very core, for the rest of her life.

Though this incident is also the hub of the novel, Hamnet is composed of multiple strands woven around it: Shakespeare’s fraught life with his parents, Agnes’s unhappy relationship with her stepmother and then with her mother-in-law, the children’s games and loyalties and fears. O’Farrell is good with tactile details, so that it is easy to picture the small apartment Agnes and her husband share, the apple shed where they make love for the first time, the woods where she goes seeking privacy for the birth of her first daughter. There’s no weighty exposition but the book feels full of historical life.

What O’Farrell does best, though–and this is no surprise, given her previous books–is to evoke emotions. Hamnet’s death is the novel’s entire premise, so grief is built into our expectations, but it was still harrowing reading her account of the illness that overcomes first his sister and then Hamnet himself, and then following Agnes through the nightmare experience of trying and failing to save him:

What O’Farrell does best, though–and this is no surprise, given her previous books–is to evoke emotions. Hamnet’s death is the novel’s entire premise, so grief is built into our expectations, but it was still harrowing reading her account of the illness that overcomes first his sister and then Hamnet himself, and then following Agnes through the nightmare experience of trying and failing to save him:

Inside Agnes’s head, her thoughts are widening out, then narrowing down, widening, narrowing, over and over again. She thinks, This cannot happen, it cannot, how will we live, what will we do, how can Judith bear it, what will I tell people, how can we continue, what should I have done, where is my husband, what will he say, how could I have saved him, why didn’t I save him, why didn’t I realize it was he who was in danger? And then, the focus narrows, and she thinks: He is dead, he is dead, he is dead.

The three words contain no sense for her. She cannot bend her mind to their meaning. It is an impossible idea that her son, her child, her boy, the healthiest and most robust of her children, should, within days, sicken and die.

She describes so well that constant restless exercise of a mother’s thoughts about her children, always checking where and how they are, “what they are doing, how they fare”:

And Hamnet? Her unconscious mind casts, again and again, puzzled by the lack of bite, by the answer she keeps giving it: he is dead, he is gone. And Hamnet? The mind will ask again. At school, at play, out at the river? And Hamnet? And Hamnet? Where is he?

Even though I knew the novel was leading me towards Hamlet, and even when I know that one answer the novel gives is that he is there, in Hamlet (“The ghost turns his head towards her, as he prepares to exit the scene. He is looking straight at her, meeting her gaze, as he speaks his final words: ‘Remember me'”) this despairingly simple but unanswerable question by a mother about her son seemed, as I was reading, much more important than any art that could be made from such a loss.

But of course Hamnet itself is built, artfully, on just that moment, and art’s ability not just to convey pain but also to console is one of the reasons we value and need it, though artists are often ambivalent or uneasy about that. “I sometimes hold it half a sin,” writes Tennyson in In Memoriam A.H.H.,

But of course Hamnet itself is built, artfully, on just that moment, and art’s ability not just to convey pain but also to console is one of the reasons we value and need it, though artists are often ambivalent or uneasy about that. “I sometimes hold it half a sin,” writes Tennyson in In Memoriam A.H.H.,

To put in words the grief I feel,

For words, like Nature, half reveal

And half conceal the Soul within.

But, for the unquiet heart and brain,

A use in measured language lies;

The sad mechanic exercise,

Like dull narcotics, numbing pain.

In words, like weeds, I’ll wrap me o’er,

Like coarsest clothes against the cold;

But that large grief which these enfold

Is given in outline and no more.

Hamlet does not compensate Agnes for Hamnet’s death, and nothing about Hamnet suggests that it should. That way lies Bardolatry, for one thing, something Hamnet scrupulously avoids. The novel is instead a form of ‘herstory.’ Inevitably, the name of Hamnet’s twin reminded me of Woolf’s imaginary Judith Shakespeare–“who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body?” But O’Farrell rejects that model too. Instead of setting her Shakespearean woman’s life up against Shakespeare’s and lamenting her failure to thrive on his terms, she gives us a life rich on its own terms and insists–and more importantly, makes us feel, through her engrossing story-telling–that it matters as much as, and also shares much more with, her husband’s life than we can understand if we focus on Hamlet at the expense of Hamnet.

This sounds really good. I won’t be reading it anytime soon, though, as the topic of the fiction is too upsetting right now for someone like me with an adult child far away, one on each coast.

LikeLike

That was really a hard part of it for me. I see Emma Donoghue’s new novel is also about a plague: in a way, these uncannily “timely” works remind us that this was always part of our horizon of possibility, even if we weren’t paying close attention.

LikeLike

I have just finished reading this book, and really enjoyed it. I noticed that the sibling relationships in this book were pretty central. The twins Judith and Hamnet, and also Agnes and her brother Batholomew. I have also just watched a production of The Twelfth Night, and I could not help thinking that the relationship of the twins Viola and Sebastian in that play might have been meant to have been inspired by the real life relationship between Shakepeare’s own twins. Of course, I have no evidence for this, it is just speculation on my part.

LikeLike

Interesting speculation! I don’t know much about Shakespeare scholarship but it’s possible this connection has been explored by critics.

LikeLike

As a retired teacher of English, I have spent many happy years teaching HAMLET and have often been curious about Hamnet and how he may have influenced Shakespeare to create HAMLET. I have never re-read a scene as often I returned to the final two pages of this book as it had grabbed me by the throat where my tears are strangled. The book all came together in a wonderful way and the final line sealed the moment in time for me. The author created moments and scenes that filled in the shadows of those times and I can never thank her enough for bringing me to those places and into the lively lives of those real people.

LikeLike