We’re caught in a universe of collision and drift, the long slow ripples of the first Big Bang as the cosmos breaks apart; the closest galaxies smash together, then those that are left scatter and flee one another until each is alone and there’s only space, an expansion expanding into itself, an emptiness birthing itself, and in the cosmic calendar as it would exist then, all humans ever did and were will be a brief light that flickers on and off again one single day in the middle of the year, remembered by nothing.

We exist now in a fleeting bloom of life and knowing, one finger-snap of frantic being, and this is it.

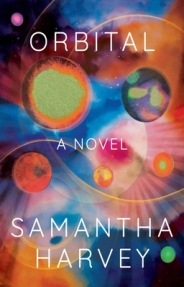

Samantha Harvey’s Orbital is wonderful. I savored it, reading with the kind of absorption that has been rare for me in recent months. Its premise is so simple: a day in the lives of six astronauts orbiting the earth on the International Space Station (maybe not the actual current one, but one very like it), watching its lights and its landscapes and its seascapes, its weather and its atmosphere, in spectacular rotating variety. It’s a risky premise, too: it could so easily have degenerated into didacticism or cliché, or just have been let down by prose that couldn’t carry us where the astronauts go, literally and mentally. But it never falters—or, to give credit where it’s due, Harvey never fails.

Much of this short book is description, and it’s all meticulous, exquisite, often poetic, without being precious:

At the brink of a continent the light is fading. The sea is flat and copper with reflected sun and the shadows of the clouds are long on the water. Asia come and gone. Australia a dark featureless shape against this last breath of light, which has now turned platinum. Everything is dimming. The earth’s horizon, which cracked open with light at so recent a dawn, is being erased. Darkness eats at the sharpness of its line as if the earth is dissolving and the planet turns purple and appears to blur, a watercolour washing away.

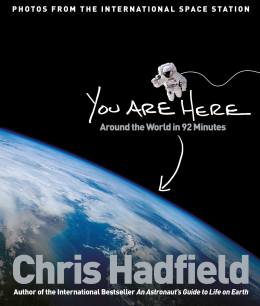

Those of us who’ve been on Twitter a long time probably remember how magical it was when Chris Hadfield was sharing his photographs of the earth from the ISS.* A few years ago I bought our family his book You Are Here as a Christmas present, and the pictures were still remarkable, but there was something about knowing they were beaming down to us from space that made them more magical the first time. You might wonder (I did, at first), what the point might be of reading about these views when you can look at them for yourself, albeit by proxy. But there’s something differently but equally magical about Harvey’s descriptions, which convey not just awe or aesthetic appreciation but a profound tenderness for our miraculous, unlikely, impermanent floating home. If only we could see it as the astronauts aboard the space station do:

The earth, from here, is like heaven. It flows with colour. A burst of hopeful colour. When we’re on that planet we look up and think heaven is elsewhere, but here is what the astronauts and cosmonauts sometimes think: maybe all of us born to it have already died, and are in an afterlife. If we must go to an improbable, hard-to-believe-in place when we die, that glassy, distant orb with its beautiful lonely light shows could well be it.

Orbital does more, though, than indulge in this potentially saccharine vision of a perfect world spoiled, pointlessly, by human squabbles, greed, and violence. This is a common starting point, the novel proposes, including for the astronauts, initially overwhelmed by the invisibility of the borders and boundaries that motivate so much hostility and cause so much death:

Orbital does more, though, than indulge in this potentially saccharine vision of a perfect world spoiled, pointlessly, by human squabbles, greed, and violence. This is a common starting point, the novel proposes, including for the astronauts, initially overwhelmed by the invisibility of the borders and boundaries that motivate so much hostility and cause so much death:

Can humans not find peace with one another? With the earth? . . . Can we not stop tyrannising and destroying and ransacking and squandering this one thing on which our lives depend?

But there’s a naivete to that perspective, and to the dismissive contempt it inspires in them (and us) towards politics, which they gradually come to understand is not something trivial but “a force so great that it has shaped every single thing on the surface of the earth”:

Every retreating or retreated glacier, every granite shoulder of every mountain laid newly bare by snow that has never before melted, every scorched and blazing forest or bush, every shrinking ice sheet, every burning oil spill . . . The hand of politics is so visible from their vantage point that they don’t know how they could have missed it at first.

The astronauts are also aware that their own astonishing vantage point is itself implicated in these forces; running through the novel is a debate, unsettled (perhaps impossible to settle), about the value of space exploration, about ideas of progress and the capacity of human invention to do as much harm as good. One of the astronauts, Chie, reflects on her own family history, including the accidents of circumstance that meant her grandfather and her mother survived the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. What story did her mother intend Chie to discern in the photograph she has given her labelled “Moon Landing Day”?

The astronauts are also aware that their own astonishing vantage point is itself implicated in these forces; running through the novel is a debate, unsettled (perhaps impossible to settle), about the value of space exploration, about ideas of progress and the capacity of human invention to do as much harm as good. One of the astronauts, Chie, reflects on her own family history, including the accidents of circumstance that meant her grandfather and her mother survived the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. What story did her mother intend Chie to discern in the photograph she has given her labelled “Moon Landing Day”?

Was she saying: look at these men going to the moon, be afraid my child at what humans can do, because we know don’t we what it all means, we know the fanfare and glory of the pioneering human spirit and we know the wonder of splitting the atom and we know what these advances can do, our grandmother knew it only too well when she stepped off the pavement to a sound she didn’t recognize and a flash that seemed both distant and so close it might have happened inside her own head . . .

Or did she want her daughter to think “look at what’s possible given desire and belief and opportunity”? Is “Moon Landing Day” an inspiration? or a cautionary tale? or both?

The vastness of space also provokes existential questions. In a chance radio encounter with another of the astronauts, a woman named Therese asks him,

Do you ever feel—do you ever feel crestfallen?

Crestfallen?

Yes, Do you ever?

I don’t know the word, what does it mean.

What does it mean? It means, do you ever wonder what is the point?

Of being in space?

Of. Do you ever. Do you sometimes to go bed in space and think, why? Does it make you wonder? Or if you’re cleaning your teeth when you’re in space. I was once on a plane on a long-haul flight and I was cleaning my teeth in the washroom and I looked out the window and I suddenly thought, what’s the point of my teeth?

The astronaut can answer only about his own experience, and especially about the experience of being in orbit (“you will not feel crestfallen, not once”). The whole novel, though, is threaded with a combination of poignancy and buoyancy about the unbearable but also breathtaking lightness of our whole existence, that is an implicit response:

Our lives here are inexpressibly trivial and momentous at once . . . We matter greatly and not at all. To reach some pinnacle of human achievement only to discover that your achievements are next to nothing and that to understand this is the greatest achievement of any life, which itself is nothing, and also much more than everything.

To write a novel about this topic without succumbing to portentousness—to embody these questions, as Harvey does, in people who live vividly enough on the page to do our thinking and feeling about them in engaging and believable ways—is an unexpected and remarkable feat, I think, but what I’ll remember most about Orbital is just how beautifully Harvey writes about the views that come and go outside the space station’s windows:

As they traverse south the colours change, the browns lighter, the palette less sombre, a range of greens from the dark of the mountainsides to the emerald of river plains to the teal of the sea. The rich purplish-green of the vast Nile Delta. Brown becomes peach becomes plum; Africa beneath them in its abstract batik. The Nile is a spillage of royal-blue ink.

How could we feel crestfallen, living among such splendor?

*You can see a gallery of Commander Hadfield’s photos here.

This sounds lovely, Rohan. I also loved Commander Hadfield’s photos from space (ah, the good old days of Twitter). One of my favorite lines from the Episcopal church Book of Common Prayer is “At your command all things came to be: the vast expanse of interstellar space, galaxies, suns, the planets in their courses, and this fragile earth, our island home.” That’s a view of earth that I think was only possible once we had seen images of it from space. Your wonderful review and the quotations you chose from Harvey made me think of these words.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Liz; I think you’d like the book – and it has the virtue (for those of us currently awash in the new academic term) of being both short and, in its own way, easy to read – very lucid. There’s a thread in the book about religious vs scientific / secular perspectives, too – not antagonistic, as that “vs” might suggest, just as questions among the astronauts about how they see things and what difference it makes.

LikeLike

I recently read Harvey’s memoir about not sleeping for a year, which I think was also very good. I’m going to keep an eye out for Orbit because I could definitely using something enthralling. (Remember the halcyon days of youth when almost every book was?)

LikeLike

Oh, I do! I’m interested in that memoir too, so it’s good to know you liked it.

LikeLike