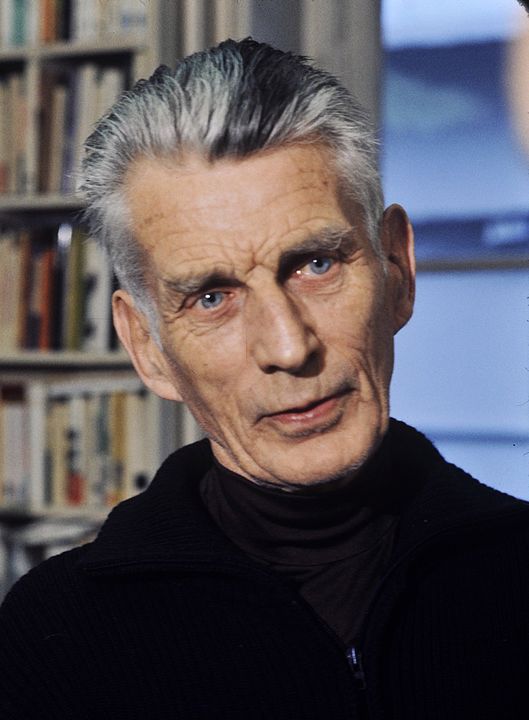

My near total first-hand ignorance of Samuel Beckett’s work would probably be a real advantage to me in David Lodge’s famous game ‘Humiliation.’ Even my second-hand knowledge is pretty limited: I have a casual idea of what Waiting for Godot is like and about, and that’s it. As with all novels steeped in another author’s lives and ideas, Jo Baker’s A Country Road, A Tree is probably better appreciated by someone else, then, someone who can do more than stumble over a reference to an ‘endgame’ and think “hey, that’s probably an allusion!” or who can read Baker’s moving description of Beckett’s epiphany about his own writing and really understand what it meant in practice:

My near total first-hand ignorance of Samuel Beckett’s work would probably be a real advantage to me in David Lodge’s famous game ‘Humiliation.’ Even my second-hand knowledge is pretty limited: I have a casual idea of what Waiting for Godot is like and about, and that’s it. As with all novels steeped in another author’s lives and ideas, Jo Baker’s A Country Road, A Tree is probably better appreciated by someone else, then, someone who can do more than stumble over a reference to an ‘endgame’ and think “hey, that’s probably an allusion!” or who can read Baker’s moving description of Beckett’s epiphany about his own writing and really understand what it meant in practice:

There is nothing grand about it; no waves, no wind, no briny spray. The world is not and never was in sympathy with him, nor with anybody else. But this is the moment when everything changes, the moment when the wide chaotic chatter and stink of it, all that wild Shem-beloved hubbub, falls away, and his eyes are trained on darkness and his ears on silence. On that stark figure, framed there on the threshold, unknowable, and his.

By this point in Baker’s novel, though, I did at least know enough about Beckett (or, about her version of Beckett) to recognize the importance of this moment as a break away from the brooding and now posthumous influence of James Joyce (“Shem”), whom Beckett assisted and idolized. “Oh you poor thing,” his friend Anna Beamish exclaims when he tells her that he helped Joyce with Finnegans Wake; “Being friends with a genius.”

Throughout A Country Road, A Tree Beckett is trying—wracked with self-doubt and haunted by the oddity of writing at all in the midst of calamity and danger—to figure out how to write his way:

He stares now at the three words he has written. They are ridiculous. Writing is ridiculous. A sentence, any sentence, is absurd. Just the idea of it: jam one word up against another, shoulder-to-shoulder, jaw-to-jaw; hem them in with punctuation so they can’t move an inch. And then hand that over to someone else to peer at, and expect something to be communicated, something understood. It’s not just pointless. It is ethically suspect.

When it’s possible, writing is an escape for him, a source of clarity and comfort, but when the spell breaks, the results bring him little satisfaction:

even to have written this little is an excess, it is an overflowing, an excretion. Too many words. There are just too many words. Nobody wants them, nobody needs them. And still they keep on, keep on, keep on coming.

This revulsion against excess is what underlies that later moment of revelation, which Baker explains further in her Author’s Note:

[The wartime years] marked the start of his paring away at language: a stripping-back of Joycean wordplay and polyphonic extravagance, towards bare bones, and silence.

Baker’s own prose in this novel strikes me as cautiously influenced by that model of “paring away,” though in that respect A Country Road, A Tree isn’t really different from a lot of conspicuously well-crafted recent novels. It is not quite as spare as Normal People, and Baker is particularly good at scene setting with concrete details and vivid imagery: the novel definitely invites the over-used term “atmospheric.” But there is little exposition; the action and dialogue do most of the work.

The specific scenes that need setting are those of Beckett’s years in occupied France, during which he played a part (a small part, he insisted) in the French Resistance. I didn’t know that this was part of Beckett’s story. Anyone’s experience of this kind would make a compelling novel (and of course there have been many other books of one kind or another about this period), and Baker does a really good job conveying the anxiety of it all: it’s an extremely tense narrative, especially from the first moment Beckett joins in with the resistance efforts. The vicarious pressure of living in constant fear of exposure or betrayal, and then with the immediate hazards of escape and living in hiding, was almost too much to add to my own currently high levels of anxiety as the third COVID wave hits Halifax and once again everyday activities feel fraught with risk. In fact, a lot about A Country Road, A Tree felt timely, as something Baker’s Beckett is particularly attuned to is the disorientation induced by the ways crisis defamiliarizes even our most routine activities and intimate spaces.

The specific scenes that need setting are those of Beckett’s years in occupied France, during which he played a part (a small part, he insisted) in the French Resistance. I didn’t know that this was part of Beckett’s story. Anyone’s experience of this kind would make a compelling novel (and of course there have been many other books of one kind or another about this period), and Baker does a really good job conveying the anxiety of it all: it’s an extremely tense narrative, especially from the first moment Beckett joins in with the resistance efforts. The vicarious pressure of living in constant fear of exposure or betrayal, and then with the immediate hazards of escape and living in hiding, was almost too much to add to my own currently high levels of anxiety as the third COVID wave hits Halifax and once again everyday activities feel fraught with risk. In fact, a lot about A Country Road, A Tree felt timely, as something Baker’s Beckett is particularly attuned to is the disorientation induced by the ways crisis defamiliarizes even our most routine activities and intimate spaces.

Following Beckett’s own lead, Baker never glamorizes Beckett’s resistance work; she doesn’t even treat it as particularly heroic. It’s true that, in retrospect at least, he came through it all pretty well, better than many of his collaborators in these efforts not to mention many, many other people. In the end what’s interesting and important about this particular story about that time and that work is what it meant to Beckett as a writer: that’s really what A Country Road, A Tree is about. Does that trivialize the war, the resistance, the deaths and suffering? I don’t think so. Beckett did more than many of us would to push back against evil, but that wasn’t his chosen work, and it seems right to pay attention to what he made of that experience, or what that experience meant to him, when its imperatives lifted and he was once again able to create unimpeded–or, at any rate, unimpeded by quite the same array of external crises. We shouldn’t let war (or COVID) convince us that things not obviously or directly related to them are not important, that the right response is to marginalize or pare away things we genuinely value. Apparently Churchill’s line about preserving the arts (“then what are we fighting for?”) is apocryphal, something he never said, but the sentiment it expresses is surely true, or at least a lot of us agree with it. To think that Beckett’s writing is less important than his efforts against the Nazis is, in a way, to lose the war. (I have questions like this about what really matters during a crisis in mind because it’s part of what I decided to write about in the essay I’ve been working on about The Balkan Trilogy—out soon, I hope.)

Following Beckett’s own lead, Baker never glamorizes Beckett’s resistance work; she doesn’t even treat it as particularly heroic. It’s true that, in retrospect at least, he came through it all pretty well, better than many of his collaborators in these efforts not to mention many, many other people. In the end what’s interesting and important about this particular story about that time and that work is what it meant to Beckett as a writer: that’s really what A Country Road, A Tree is about. Does that trivialize the war, the resistance, the deaths and suffering? I don’t think so. Beckett did more than many of us would to push back against evil, but that wasn’t his chosen work, and it seems right to pay attention to what he made of that experience, or what that experience meant to him, when its imperatives lifted and he was once again able to create unimpeded–or, at any rate, unimpeded by quite the same array of external crises. We shouldn’t let war (or COVID) convince us that things not obviously or directly related to them are not important, that the right response is to marginalize or pare away things we genuinely value. Apparently Churchill’s line about preserving the arts (“then what are we fighting for?”) is apocryphal, something he never said, but the sentiment it expresses is surely true, or at least a lot of us agree with it. To think that Beckett’s writing is less important than his efforts against the Nazis is, in a way, to lose the war. (I have questions like this about what really matters during a crisis in mind because it’s part of what I decided to write about in the essay I’ve been working on about The Balkan Trilogy—out soon, I hope.)  And it is probably in this case best, anyway, not to consider these things as in opposition. Writers’ experiences become their art, and that’s what Baker is primarily exploring: how being alone and afraid and constantly confronted with irrationality and violence and threats both literal and existential brought Beckett to an understanding of what he wanted to write and how.

And it is probably in this case best, anyway, not to consider these things as in opposition. Writers’ experiences become their art, and that’s what Baker is primarily exploring: how being alone and afraid and constantly confronted with irrationality and violence and threats both literal and existential brought Beckett to an understanding of what he wanted to write and how.

I think one reason I hadn’t pursued any further information about or experience of Beckett was that what I (vaguely) thought I knew about Waiting for Godot made me think I’d find his work both confusing and kind of depressing. Baker’s novel showed me something more appealing—not easy answers about “the meaning of life” or uplifting stories of courage under fire, but reasons for the kind of quiet optimism that depends on just doing the best we can:

Things are getting better. Things are becoming sound. There’s asphalt on the roads and on the paths. There’s glass, or something like glass, in all the windows. There’s lino on the labour-room floor—since there is breeding still, even now, even in this devastation. There are curtains round the beds, and clean sheets and warm blankets neatly tucked in. . . There is tea and there are biscuits and there is bread-and-jam when it is required, and it is often required. There’s kindness here. There’s decency among the ruins. It is something to behold.