Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil.

Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil.

Anyone who’s read Pride and Prejudice will immediately recognize this moment. Jane has come down with a cold thanks to her mother’s insistence that she ride to Netherfield “because it seems likely to rain; and then you must stay all night”—a highly successful strategy, as it turns out. Elizabeth, “feeling really anxious, was determined to go to her, though the carriage was not to be had; and as she was no horsewoman, walking was her only alternative.” And so she sets out on foot,

crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and springing over puddles with impatient activity, and finding herself at last within view of the house, with weary ankles, dirty stockings, and a face glowing with the warmth of exercise.

The residents of Netherfield are shocked at her impropriety, but though they notice that her petticoat is “six inches deep in mud,” not one of them gives a moment’s thought to the extra work Elizabeth’s “country-town indifference to decorum” creates for the household staff. Neither, as far as we know, do Jane and Elizabeth: in this privileged indifference to the labor that supports their lifestyle, if in nothing else, they are very much at one with their hosts.

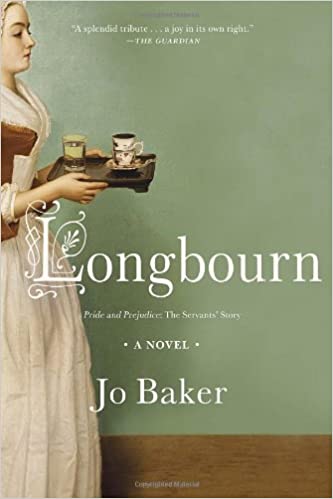

Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. (Exhibit A, the worst.) I have also been tired of the endless appetite for all things Austen for a long time: so many of the results seem either too fannish or just plain parasitic. Finally, I am not by personal taste a Janeite (I like only two of her novels, though I am capable, in my better moods, of appreciating what’s excellent about a couple of the others). It just seemed so unlikely that I’d enjoy Longbourn!

Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. (Exhibit A, the worst.) I have also been tired of the endless appetite for all things Austen for a long time: so many of the results seem either too fannish or just plain parasitic. Finally, I am not by personal taste a Janeite (I like only two of her novels, though I am capable, in my better moods, of appreciating what’s excellent about a couple of the others). It just seemed so unlikely that I’d enjoy Longbourn!

And yet enjoy it I did, quite a lot, which naturally has got me thinking about why—about what Baker does that worked for me where other books in the same vein have failed. I overcame my prejudices enough to try it in the first place because I really liked A Country Road, A Tree: the writer of that smart, sensitive novel about one great writer probably (I reasoned) would not be cheap or shallow in her novel inspired by another. But A Country Road, A Tree is a biographical novel, a different subcategory of literary homage: it undertakes to investigate the writing process, not to rewrite the results—an approach which risks pitting the new author against the old, or, worse, setting the new author above the old. I think Longbourn succeeds because it sits beside the original: Baker is rounding out the story Austen tells, adding to it in ways that inevitably complicate how we think about it, but she is also clearly writing her own novel, and it stands up well on those terms. In fact, at times I wondered if (marketing advantage aside) Baker really needed the Austen hook: couldn’t Longbourn just have been a historical novel about servants in any elegant Regency household?

I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its excessively well-known inspiration. It was fun to know exactly what was going on upstairs even when Baker’s characters don’t—when Darcy first proposes to Elizabeth at Hunsford, for example. Sarah, who has accompanied Lizzie on the trip to see Charlotte, now Mrs. Collins, is busy with her own thoughts, especially about her relationship with James Smith, when she hears “a door shut within the house”:

I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its excessively well-known inspiration. It was fun to know exactly what was going on upstairs even when Baker’s characters don’t—when Darcy first proposes to Elizabeth at Hunsford, for example. Sarah, who has accompanied Lizzie on the trip to see Charlotte, now Mrs. Collins, is busy with her own thoughts, especially about her relationship with James Smith, when she hears “a door shut within the house”:

There were quick footfalls coming down the hall. She got up off the step and stood aside just in time, or he would have walked straight through her; the front door was whisked wide, and Mr. Darcy strode past her shadow, and marched down the path. He left the gate swinging … Back in the house, she crept down the hall and cocked an ear outside the parlour door. She could hear the quiet sounds of Elizabeth crying.

I guess we do need to know Pride and Prejudice to appreciate this moment fully, but that doesn’t mean Longbourn needed to be attached to the other novel in this way to fulfill its own (other) aims.

The connection is more significant in the other direction, I think: having read Longbourn, you are likely to be more aware of the elements that are absent from Pride and Prejudice the next time you read Austen’s novel. I say “absent” rather than “missing from” because I think the former allows us to acknowledge the limited scope of Pride and Prejudice without insisting on that as a fault in it: it is what it is, and Longbourn is something else, is about something else—not the same themes of manners and morals, not the same political themes or philosophies, as Pride and Prejudice, but other social and political themes, including class (which of course Austen’s novel is also about), race, and empire, topics which are relevant to the lives of Austen’s characters (and especially to their wealth) in ways the original novel does not explicitly acknowledge. Of course the result is some (mostly implicit) critique, especially around the source of the Bingleys’ wealth, which Austen tells us was “acquired by trade” but which Baker attributes more specifically to sugar. “I would love to be in sugar,” exclaims the little maid Polly.

“You’d go sailing out”—James traced a triangle in the air with a fork—”loaded to the gunwales with English guns and ironware. You’d follow the trade-winds south to Africa … In African, you can trade all that, and guns, for people; you load them up in your hold, and you ship them off to the West indies, and trade them there for sugar, and then you ship the sugar back home to England. The triangular Trade, they call it.

“I didn’t know they paid for sugar that way,” says Polly uncomfortably, “with people.” Another pointed moment comes near the end, when Sarah tells Elizabeth (whom she is now serving at Pemberley) that she is leaving. “But where will you go, Sarah?” Elizabeth asks; “What can a woman do, all on her own, and unsupported?” “Work,” Sarah replies. “I can always work.” That, of course, is an alternative Elizabeth herself never contemplates when faced with the dire prospect of marrying Mr. Collins or risking poverty.

But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her.

But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her.

Thank you very much. It’s rare to find a review taking Austen sequels seriously. I am passionately involved with Austen’s writing (all of it), but don’t usually read the sequels. I have read a number anyway as I’m so interested in Austen and things Austen and found Longbourn one of the best. Partly I also put it down to her developing these marginal or outside characters; it reminded me of Mary Reilly (and other books), and if Baker had developed the Peninsular war more, Longbourn might be a historical novel in its own right. Unfortunately (I think) she stays within the parameters of Pride and Prejudice mostly. I thought she also used elements from the Austen film adaptations.

Here is my probably overlong review:

I found PDJames’s Death of Pemberley weak and poor, but the movie very good, again an appropriation.

Ellen

LikeLike

I have started Death at Pemberley a couple of times and always given it up. I might try the adaptation, though, given your comment!

Thank you for the link to your own blog post! You cover a lot more ground there than I do. The Downton Abbey connection definitely seems like an important one, and it seems like an adaptation of Baker’s novels that played up that + Austen would be an even bigger hit than Bridgerton. 🙂

LikeLike

Interesting. I’d passed this off as yet another Austen fanfic.

LikeLike

Yes, I always had too, and mostly they just don’t interest me.

LikeLike

Your post on this reminds me that a former bookshop colleague was wildly enthusiastic about Baker’s previous book, ‘A Country Road, A Tree’, when it came out a few years ago…and I can see from your commentary above that you very enjoyed it too. I suspect that’s more my bag than Longbourn, as I’m happier in the mid-20th-century than in Austen’s milieu, but this does sound of interest for the right reader. Thank you for the nudge about Baker in general, very useful indeed.

LikeLike

I did really like A Country Road, A Tree. Now I’ve read three of Baker’s books and I think I will be looking up her earlier ones.

LikeLike