The re-dipping of the dishes was a small matter, but the emotional texture of married life is made up of small matters. This one had become invested with a fatal quality.

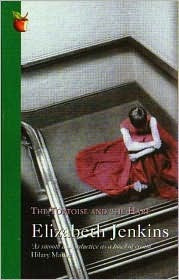

Elizabeth Jenkins’s The Tortoise and the Hare is a small gem of a novel–not a sparkly diamond, but something a bit overcast and somber despite its polish, like a black pearl. It is a wry small-scale tragedy, or possibly, if you feel less sympathetic towards its main characters, a bleak domestic comedy. As fa as its plot goes, it is modest and almost painfully intimate: it tells the superficially simple story of a marriage coming apart. The explicit cause of its collapse is an affair, but as self-help books often suggest, adultery can be a symptom of a faltering relationship as much as an explanation for it, and that is certainly true for the characters in The Tortoise and the Hare.

Elizabeth Jenkins’s The Tortoise and the Hare is a small gem of a novel–not a sparkly diamond, but something a bit overcast and somber despite its polish, like a black pearl. It is a wry small-scale tragedy, or possibly, if you feel less sympathetic towards its main characters, a bleak domestic comedy. As fa as its plot goes, it is modest and almost painfully intimate: it tells the superficially simple story of a marriage coming apart. The explicit cause of its collapse is an affair, but as self-help books often suggest, adultery can be a symptom of a faltering relationship as much as an explanation for it, and that is certainly true for the characters in The Tortoise and the Hare.

Most of the novel is told from the point of view of Imogen Gresham, the pretty and always-pleasing wife of an eminent lawyer, Evelyn. Her graceful passivity has been the perfect complement to his assertive form of masculinity, but by the time we meet them things have shifted just enough that she sometimes finds him overbearing or indifferent while he (though we mostly have to infer this from his actions) has tired of her lack of force, which seems to him (and to us as well, I think) like lack of character. Around them is a small circle of friends they hold in varying degrees of intimacy and affection: there’s Paul, for instance, who still quietly adores Imogen even though he is married to someone else, and the flashy beauty Zenobia, who can’t quite believe that Evelyn isn’t smitten with her.

The most important of these secondary characters is the Greshams’ neighbor, Blanche Silcox. Blanche is the hare of the title to Imogen’s tortoise, or so Carmen Callil proposes in her Afterword to my Virago edition, “because though she has raced off with the trophy husband, where love is betrayed once, so it may be again”–in other words, Blanche appears to be a winner. It could also be argued, though, that Blanche is actually the stealthily victorious tortoise. She is such an unlikely competitor for Evelyn’s love that for some time Imogen simply refuses to countenance the possibility. Where Imogen is refined, elegant, soft-spoken, and accommodating, Blanche is ungainly, strangely dressed, and blithely opinionated. And yet it is she Evelyn ultimately loves.

Jenkins’s title reminded me of a favorite passage from Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac. “In my books,” says its romance-novelist protagonist,

it is the mouse-like unassuming girl who gets the hero. . . . The tortoise wins every time. This is a lie, of course. . . . In real life, of course, it is the hare who wins. . . . Aesop was writing for the tortoise market. Axiomatically, . . . hares have no time to read. They are too busy winning the game. The propaganda goes all the other way, but only because it is the tortoise who is in need of consolation.

Imogen (as her name implies) has all the qualities of a conventional romantic heroine of the English rose variety, the kind of woman who should win the game. That’s certainly what she thinks, and her very expectation of success is, one of her friends eventually suggests, what defeats her:

Imogen (as her name implies) has all the qualities of a conventional romantic heroine of the English rose variety, the kind of woman who should win the game. That’s certainly what she thinks, and her very expectation of success is, one of her friends eventually suggests, what defeats her:

women who are attractive in that sort of way, it’s their thing. They never think about anything else, practically. That’s why they’re such good value, up to a point. But an affront to that side of them, and they’re beaten to the floor.

If you have been taking Imogen’s perspective too much at face value, as I realized by the end of the novel that I had been doing, this will sound not just unfriendly but sexist–“good value”?! It’s not entirely unfair, though: it takes Imogen a long time to do anything, for her marriage or, more importantly, for herself. She has fulfilled her conventional role so perfectly she has inadvertently proven what a disappointing one it is, for her as well as her husband. Blanche, in contrast, is quite literally behind the wheel, driving herself and Evelyn around, walking, fishing, and otherwise not being the kind of woman Imogen thinks men fall in love with.

Overall I side with Imogen’s friend Cecil, who has little patience for Blanche’s moral equivocations: “it occurred to Cecil that had the question been one of embezzlement, theft or poaching, passing a worthless cheque or doping a racehorse, Miss Silcox would have found no difficulty in deciding what virtue was.” Still, I kept thinking as I read The Tortoise and the Hare that, precisely because she is such an unlikely figure of romance, in a different novel Blanche might well be the one I was rooting for. On Brookner’s terms, I think it is Blanche who is the tortoise–plain, smart, independent–and so Evelyn’s love for her, when he finally and unequivocally declares it, is potentially as subversive as Rochester’s preferring Jane Eyre to Blanche Ingram.

The Tortoise and the Hare is not that book, though, any more than it is a wholly sympathetic picture of Imogen’s plaintive suffering. Still, all the affect of the novel–its emotional texture–is on Imogen’s side: I actually found it quite stressful being immersed in her anxious uncertainty as she watched Evelyn’s relationship with Blanche reach further and further into the corners of her own life, including her awkward relationship with her son Gavin (who is, in his turn, an unattractive reiteration of his father’s least sensitive aspects). Once the truth is impossible to deny or ignore, her indecision is painful but completely understandable. “You did use to have very liberal ideas about these matters,” Evelyn says when finally confronted. “But I did not ever imagine quite this sort of thing,” says Imogen: “so domestic, like a wife already.” She thought she could cope with “an ornament, an addition,” but instead she has found herself displaced, redundant, in the one role she knows how to fill.

The Tortoise and the Hare is not that book, though, any more than it is a wholly sympathetic picture of Imogen’s plaintive suffering. Still, all the affect of the novel–its emotional texture–is on Imogen’s side: I actually found it quite stressful being immersed in her anxious uncertainty as she watched Evelyn’s relationship with Blanche reach further and further into the corners of her own life, including her awkward relationship with her son Gavin (who is, in his turn, an unattractive reiteration of his father’s least sensitive aspects). Once the truth is impossible to deny or ignore, her indecision is painful but completely understandable. “You did use to have very liberal ideas about these matters,” Evelyn says when finally confronted. “But I did not ever imagine quite this sort of thing,” says Imogen: “so domestic, like a wife already.” She thought she could cope with “an ornament, an addition,” but instead she has found herself displaced, redundant, in the one role she knows how to fill.

In the end it’s hard to know quite how to weigh the poignancy of her loss against the happiness that gives Blanche a new and enviable radiance. That ambivalence makes The Tortoise and the Hare more interesting: it reflects the subtlety and complexity of people’s feelings for each other. I thought the novel’s ending also pressed us to recognize, with Imogen, that happiness is not something we should rely on other people for. “I must improve,” she finally and rightly says; “There is a very great deal to be done.”

I’m bookmarking this, because, great minds? kindred spirits? the stars align? it’s next on my TBR list, right here next to me once I finish Jamaica Inn (which is terrific, btw).

LikeLike

I loved Jamaica Inn! I’m always surprised when people who love other DduM say they found it too slow.

LikeLike

What! Too slow?! Something happens every chapters, somehow dramatic and surprising. I was, as it’s my first du Maurier, surprised at how sophisticated and atmospheric it is. I though I was getting Heyer and got Castle of Otranto … LOL!

But seriously, it’s a hell of a read. And the heroine, plain Mary Yellan, what a voice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s an interestingly nuanced book, isn’t it? I read it a while ago and still think about it. I felt it was a book in which the romantic “success” of either woman was meaningless because it was about which of them best served Evelyn’s needs — neither the tortoise or the hare really wins because the prize is Evelyn, and you can never stop running the race for his favour or he’ll tire of you. Blanche doesn’t win because she has more textured individuality than Imogen, though you could write a story which gave Blanche’s character archetype an only slightly different emphasis in which this was the case. She wins because she can serve Evelyn better, adeptly providing him with physical comforts and sharing an understanding of “the done thing”. Imogen’s moony romantic quality should have been the preface to her demonstrating the ability to offer those other things after marriage. I remember feeling the conversation in which Blanche pours scorn on the working classes seeking treatment from the newly established NHS is the place where Jenkins most takes sides between the two women. Blanche is the character who most deliberately chooses to identify herself with power, in a world where as a woman you will be on your own if you don’t. On the surface she is an unconventional, independent love interest. Under the surface she isn’t. In some ways Imogen, both despite and because of her passivity, is more of an end in herself. Those closest to her don’t find her very nourishing and while this is generally seen as a bad thing here there’s something of resistance in it. The loss of her marriage is both punishment and release.

LikeLike