This post may be a contribution to the vast genre of “someone finally noticed something obvious to everyone else,” but it is about something that has been a bit of a quiet revelation to me, a small insight that on my good days (I do still have a few, in spite of it all) makes me feel not just better about what I’ve done so far but optimistic about what I might do next. So I thought it was worth saying something about here!

This post may be a contribution to the vast genre of “someone finally noticed something obvious to everyone else,” but it is about something that has been a bit of a quiet revelation to me, a small insight that on my good days (I do still have a few, in spite of it all) makes me feel not just better about what I’ve done so far but optimistic about what I might do next. So I thought it was worth saying something about here!

Recently we’ve been really enjoying the shows Landscape Artist of the Year and Portrait Artist of the Year (in Canada, they air on the ‘Makeful’ channel, which is also where you can watch the Great British Sewing Bee, in case that’s your jam). Like all ‘reality’ shows, they are a bit artificial and micro-managed, and the gamification of creativity can seem problematic: much more so than with, say, baking shows, where there’s something definitive about a “soggy bottom” or a collapsed soufflé, in these shows there’s something mysterious to us about the judging, as the judges often rate most highly the paintings we thought were clearly the worst. It’s thought-provoking, in that it raises a lot of questions about what we and they are looking for: clearly they are seeing things we aren’t, or valuing things we don’t.

But the question of artistic merit (while one I am always interested in puzzling over) is not actually what’s on my mind these days. Instead, I’ve been thinking about how these shows celebrate the value of what I will call (for lack of a better word) idiosyncrasy, by which, in this context, I mean the value of finding the distinctive approach that is yours, or the specific thing you are good at and doing that thing, not some other thing. Given the identical task (paint this person, paint this scenery) the artists all do every single step differently: some sketch first in pencil, some slather background colors on their canvas; some work in meticulous grids, some block in big shapes; some use pastels, some watercolors or oils or acrylics. In the episode we watched last night, someone worked on scratchboard, which I’d never heard of before. The end results are also enormously various, ranging from photographic realism to much more abstract or conceptual versions of the assigned subject.

But the question of artistic merit (while one I am always interested in puzzling over) is not actually what’s on my mind these days. Instead, I’ve been thinking about how these shows celebrate the value of what I will call (for lack of a better word) idiosyncrasy, by which, in this context, I mean the value of finding the distinctive approach that is yours, or the specific thing you are good at and doing that thing, not some other thing. Given the identical task (paint this person, paint this scenery) the artists all do every single step differently: some sketch first in pencil, some slather background colors on their canvas; some work in meticulous grids, some block in big shapes; some use pastels, some watercolors or oils or acrylics. In the episode we watched last night, someone worked on scratchboard, which I’d never heard of before. The end results are also enormously various, ranging from photographic realism to much more abstract or conceptual versions of the assigned subject.

Watching the artists just do their thing, which they are often asked to explain but never expected to excuse or justify, I realized how often in my own life I have felt inept or inadequate because I couldn’t do things in a certain way, or do certain kinds of things well, across a whole range of activities from the professional (writing and scholarship) to the personal (knitting or cooking or quilting, for example … or drawing). I have often felt sheepish about the variations I was reasonably good at, or enjoyed doing even if I wasn’t that good at them, as if they signaled my limitations, not my own special (if modest!) gifts. I struggled for a long time to make quilts in traditional pieced patterns, which I love the look of–but I have always found simple applique patterns more fun and gotten better results with them. I thought this meant I was not good at quilting. I struggled for a long time to learn to knit and have never really got the knack of it; once I figured out how to make granny squares, I quite enjoyed crochet. I thought this uneven result meant I was pretty mediocre at yarn crafts. One crochet pattern I have found particularly congenial, for whatever reason, is the so-called ‘virus shawl’; it didn’t occur to me to celebrate this as my niche rather than wonder why I couldn’t do other patterns as readily.

Watching the artists just do their thing, which they are often asked to explain but never expected to excuse or justify, I realized how often in my own life I have felt inept or inadequate because I couldn’t do things in a certain way, or do certain kinds of things well, across a whole range of activities from the professional (writing and scholarship) to the personal (knitting or cooking or quilting, for example … or drawing). I have often felt sheepish about the variations I was reasonably good at, or enjoyed doing even if I wasn’t that good at them, as if they signaled my limitations, not my own special (if modest!) gifts. I struggled for a long time to make quilts in traditional pieced patterns, which I love the look of–but I have always found simple applique patterns more fun and gotten better results with them. I thought this meant I was not good at quilting. I struggled for a long time to learn to knit and have never really got the knack of it; once I figured out how to make granny squares, I quite enjoyed crochet. I thought this uneven result meant I was pretty mediocre at yarn crafts. One crochet pattern I have found particularly congenial, for whatever reason, is the so-called ‘virus shawl’; it didn’t occur to me to celebrate this as my niche rather than wonder why I couldn’t do other patterns as readily.

Switching to professional examples, I found most of the critical approaches I was expected to engage with as a graduate student inaccessible, and none of the criticism I actually ended up finding meaningful and useful was ever assigned. I often interpreted this as evidence of my unfitness for academic scholarship, but what if it isn’t, but is just me finding my academic style? I seem to be pretty good at some kinds of essays – ones that think through a body of work, for example, like all of Dick Francis’s novels, or all of P. D. James’s – and not so good at, or at least not so eager to try, or able to pitch, other kinds. What if the pleasure I take in doing that kind of work is not a sign of weakness, but (and I think this is important) not a sign of strength either: what if I thought of it instead without those hierarchical judgments, just as a mark of my idiosyncrasy, of my individual intellectual style? What if the freedom and curiosity and occasional exhilaration I experience when I’m writing on my blog, for that matter, is also about finding my own way, using the tools that feel natural in my hands, making this site a self-portrait in words rather than a shelter from the uncongenial demands of “real” academic writing? What if feeling some comfort, pleasure, and ease in a particular kind of work means that it fits, and that’s a good thing?

Switching to professional examples, I found most of the critical approaches I was expected to engage with as a graduate student inaccessible, and none of the criticism I actually ended up finding meaningful and useful was ever assigned. I often interpreted this as evidence of my unfitness for academic scholarship, but what if it isn’t, but is just me finding my academic style? I seem to be pretty good at some kinds of essays – ones that think through a body of work, for example, like all of Dick Francis’s novels, or all of P. D. James’s – and not so good at, or at least not so eager to try, or able to pitch, other kinds. What if the pleasure I take in doing that kind of work is not a sign of weakness, but (and I think this is important) not a sign of strength either: what if I thought of it instead without those hierarchical judgments, just as a mark of my idiosyncrasy, of my individual intellectual style? What if the freedom and curiosity and occasional exhilaration I experience when I’m writing on my blog, for that matter, is also about finding my own way, using the tools that feel natural in my hands, making this site a self-portrait in words rather than a shelter from the uncongenial demands of “real” academic writing? What if feeling some comfort, pleasure, and ease in a particular kind of work means that it fits, and that’s a good thing?

Perhaps this is just another way to explain what it is like to try to break out of certain academic habits of mind, and to recognize just how pervasive they are. Academia is an environment in which (for some good reasons, to be sure) we spend a lot of time trying to fit ourselves – and our students – to specific models, trying to conform to standards and practices, to produce certain kinds of outcomes and results, to attain certain styles of writing. We rarely have either the time or the courage for idiosyncrasy, and it isn’t likely to be rewarded. I’m not rejecting the whole idea of standards or rigor or expertise as foundational values. I’m sure it’s true that all of the artists on these shows have had to master a lot of fundamental skills: they can all draw anatomically correct figures, create likenesses, sketch landscape elements to scale. They have an enormous amount of technical know-how as well. But the whole point of being an artist is to go past that common ground into your own territory, which is where you really expand and define yourself. Maybe that is what’s different: a lot of academics spend a long time in that first phase, the “do it this way” phase, which fills us with lasting fear that we aren’t doing it right and so we get stuck there.

Perhaps this is just another way to explain what it is like to try to break out of certain academic habits of mind, and to recognize just how pervasive they are. Academia is an environment in which (for some good reasons, to be sure) we spend a lot of time trying to fit ourselves – and our students – to specific models, trying to conform to standards and practices, to produce certain kinds of outcomes and results, to attain certain styles of writing. We rarely have either the time or the courage for idiosyncrasy, and it isn’t likely to be rewarded. I’m not rejecting the whole idea of standards or rigor or expertise as foundational values. I’m sure it’s true that all of the artists on these shows have had to master a lot of fundamental skills: they can all draw anatomically correct figures, create likenesses, sketch landscape elements to scale. They have an enormous amount of technical know-how as well. But the whole point of being an artist is to go past that common ground into your own territory, which is where you really expand and define yourself. Maybe that is what’s different: a lot of academics spend a long time in that first phase, the “do it this way” phase, which fills us with lasting fear that we aren’t doing it right and so we get stuck there.

As I said, maybe I’m just restating the obvious, and maybe what I’m really probing is more an individual neurosis and not a general condition (though I expect a lot of academics will recognize my description of the way we are trained to think and work). Still, when I started thinking about idiosyncrasy in this way it felt exciting and even a bit empowering. Imagine being free to be you and me in this way! I’m not 100% sure what that would even mean for me in practice, especially as a writer, but for now I’m going to just sit with the idea that it’s not just OK but actually desirable to do my own thing rather than feeling awkward or deficient because I can’t or don’t want to do some other thing.

As I said, maybe I’m just restating the obvious, and maybe what I’m really probing is more an individual neurosis and not a general condition (though I expect a lot of academics will recognize my description of the way we are trained to think and work). Still, when I started thinking about idiosyncrasy in this way it felt exciting and even a bit empowering. Imagine being free to be you and me in this way! I’m not 100% sure what that would even mean for me in practice, especially as a writer, but for now I’m going to just sit with the idea that it’s not just OK but actually desirable to do my own thing rather than feeling awkward or deficient because I can’t or don’t want to do some other thing.

I read a book that wasn’t for work! In fact, I read two books! I cant remember another teaching term when this has felt like such an accomplishment. Sometimes I read the most, paradoxically, when I am otherwise the busiest! There’s something enervating about the way I am busy this term, though, including (

I read a book that wasn’t for work! In fact, I read two books! I cant remember another teaching term when this has felt like such an accomplishment. Sometimes I read the most, paradoxically, when I am otherwise the busiest! There’s something enervating about the way I am busy this term, though, including ( I’m not going to recapitulate the intricate details of the stories either book tells. Briefly, in case neither title is familiar, Say Nothing starts from the abduction of a Belfast woman named Jean McConville by (it is presumed) the IRA, and from that harrowing incident layers on contexts and characters to explore the social, political, and especially moral complexities of life in Northern Ireland during the ‘troubles.’ “Who should be held accountable for a shared history of violence?” Keefe asks? At every turn, difficult questions arise about motives, culpability, and, ultimately, accountability. One example, about a key player in the IRA’s so-called “nutting squad” who turned out to be an extremely valuable informant (if you think about it, you’ll figure out how they got that name and you will shudder, as you will often reading this book):

I’m not going to recapitulate the intricate details of the stories either book tells. Briefly, in case neither title is familiar, Say Nothing starts from the abduction of a Belfast woman named Jean McConville by (it is presumed) the IRA, and from that harrowing incident layers on contexts and characters to explore the social, political, and especially moral complexities of life in Northern Ireland during the ‘troubles.’ “Who should be held accountable for a shared history of violence?” Keefe asks? At every turn, difficult questions arise about motives, culpability, and, ultimately, accountability. One example, about a key player in the IRA’s so-called “nutting squad” who turned out to be an extremely valuable informant (if you think about it, you’ll figure out how they got that name and you will shudder, as you will often reading this book):

The second book I recently finished is also an accomplished work of narrative nonfiction, Karen Abbott’s The Ghosts of Eden Park. Its long subtitle tells you a lot about its flavour: The Bootleg King, the Women who Pursued Him, and the Murder that Shocked Jazz-Age America. My interest in this book was piqued by our recent viewing of the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, in which Abbot’s main character, the bootlegger George Remus, features prominently. It was fun learning how many aspects of his character were based on reality, such as his peculiar habit of referring to himself in the third person.

The second book I recently finished is also an accomplished work of narrative nonfiction, Karen Abbott’s The Ghosts of Eden Park. Its long subtitle tells you a lot about its flavour: The Bootleg King, the Women who Pursued Him, and the Murder that Shocked Jazz-Age America. My interest in this book was piqued by our recent viewing of the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, in which Abbot’s main character, the bootlegger George Remus, features prominently. It was fun learning how many aspects of his character were based on reality, such as his peculiar habit of referring to himself in the third person. They aren’t, though: that’s just not the book she is writing, and of course that’s fine. She tells a brisk, entertaining, fairly sensational story about Remus, whose success as a bootlegger actually is just background for what becomes his obsessive love-hate relationship with his wife Imogene. While Remus is being prosecuted and imprisoned, Imogene begins an affair with one of the agents who had investigated him, which drives Remus (or so he later argues in court) insane. He never seems very stable: Abbott’s reports from his own statements and writings as well as other people’s reports and observations make him out to be a highly erratic and, frankly, extremely annoying character, someone who never at any moment aroused a glimmer of empathy in me. This is a problem, or it was for me, because after a while reading about his antics and histrionics was like watching some kind of strange zoo animal go berserk and hoping eventually someone will just sedate him and get it over with. Imogene is no better: she’s an opportunist who lies and manipulates and takes everything she can from Remus. When he shoots her in the middle of Chicago’s Eden Park (not a spoiler – this is where the book itself begins!) it seems pretty grim, but by the time we circle around to it after hundreds of pages of backstory, I felt much less, rather than much more, horror–which, in my view anyway, is something of a failure for the book, or perhaps more generally for the project. We should not be indifferent to murder: it should not feel like no more than a plot point. It is, as P. D. James says over and over in her essays on detective fiction, “the unique crime.” That Remus and Imogene and most of their cohort of friends and accomplices have become indifferent to its moral significance is telling, about them and about the world they (thought they) lived in. I was disappointed, though, that Abbott’s treatment more or less accepted their terms. It’s a wild story, with many remarkable twists, but Abbott’s exhaustive research didn’t make it seem any less shallow.

They aren’t, though: that’s just not the book she is writing, and of course that’s fine. She tells a brisk, entertaining, fairly sensational story about Remus, whose success as a bootlegger actually is just background for what becomes his obsessive love-hate relationship with his wife Imogene. While Remus is being prosecuted and imprisoned, Imogene begins an affair with one of the agents who had investigated him, which drives Remus (or so he later argues in court) insane. He never seems very stable: Abbott’s reports from his own statements and writings as well as other people’s reports and observations make him out to be a highly erratic and, frankly, extremely annoying character, someone who never at any moment aroused a glimmer of empathy in me. This is a problem, or it was for me, because after a while reading about his antics and histrionics was like watching some kind of strange zoo animal go berserk and hoping eventually someone will just sedate him and get it over with. Imogene is no better: she’s an opportunist who lies and manipulates and takes everything she can from Remus. When he shoots her in the middle of Chicago’s Eden Park (not a spoiler – this is where the book itself begins!) it seems pretty grim, but by the time we circle around to it after hundreds of pages of backstory, I felt much less, rather than much more, horror–which, in my view anyway, is something of a failure for the book, or perhaps more generally for the project. We should not be indifferent to murder: it should not feel like no more than a plot point. It is, as P. D. James says over and over in her essays on detective fiction, “the unique crime.” That Remus and Imogene and most of their cohort of friends and accomplices have become indifferent to its moral significance is telling, about them and about the world they (thought they) lived in. I was disappointed, though, that Abbott’s treatment more or less accepted their terms. It’s a wild story, with many remarkable twists, but Abbott’s exhaustive research didn’t make it seem any less shallow. The one element of Abbott’s book that will really stick with me is Mabel Walker Willibrandt. One of my questions watching Boardwalk Empire was about the plausibility of the character Esther Randolph, the U. S. Attorney who tries to bring down Nucky Thompson. It turns out that there were a few women who made careers in the law even that early in the 20th century, and Willibrandt was one of them. She and her “Mabelmen” ought to have their own TV series, if you ask me: she is bold, fierce, and sharply self-conscious about the extra burden her sex adds to her work. “Why the devil they have to put that ‘girlie girlie’ tea party description every time they tell anything a professional woman does,” she wrote to her parents,

The one element of Abbott’s book that will really stick with me is Mabel Walker Willibrandt. One of my questions watching Boardwalk Empire was about the plausibility of the character Esther Randolph, the U. S. Attorney who tries to bring down Nucky Thompson. It turns out that there were a few women who made careers in the law even that early in the 20th century, and Willibrandt was one of them. She and her “Mabelmen” ought to have their own TV series, if you ask me: she is bold, fierce, and sharply self-conscious about the extra burden her sex adds to her work. “Why the devil they have to put that ‘girlie girlie’ tea party description every time they tell anything a professional woman does,” she wrote to her parents, I realize there’s something of an apples and oranges problem with comparing these two books. It’s inevitable, though, that reading books back to back prompts some consideration of what they do or don’t have in common. I would say both are good of their kind, but Say Nothing is of a more important kind: it demands that we look at its events, not as colourful stories about the past, but as parts of our ongoing, imperfect, and morally weighty attempts to understand the place and consequences of violence, especially in our politics. It’s easy to condemn violence, but absolute pacifism can be (as Vera Brittain found, in a different context) difficult to defend. Even if there are cases in which violence seems necessary or justified, though, so many questions still remain. We are watching the Norwegian series Occupied right now, which of course is speculative fiction, not history, but I think it too provokes these questions. At what point would you agree with blowing something up, or worse? My complaint about The Ghosts of Eden Park is that not only do none of the people Abbott talks about seem to care very deeply about these problems – Abbott herself, or at least her book, also does not engage with them. In her book, the story is everything, and it’s actually a pretty cheap and lurid one. Maybe this is not so different, really, from the standards I apply to fiction: I have always found it (pace Oscar Wilde) important to be earnest, at least where matters of moral weight are involved.

I realize there’s something of an apples and oranges problem with comparing these two books. It’s inevitable, though, that reading books back to back prompts some consideration of what they do or don’t have in common. I would say both are good of their kind, but Say Nothing is of a more important kind: it demands that we look at its events, not as colourful stories about the past, but as parts of our ongoing, imperfect, and morally weighty attempts to understand the place and consequences of violence, especially in our politics. It’s easy to condemn violence, but absolute pacifism can be (as Vera Brittain found, in a different context) difficult to defend. Even if there are cases in which violence seems necessary or justified, though, so many questions still remain. We are watching the Norwegian series Occupied right now, which of course is speculative fiction, not history, but I think it too provokes these questions. At what point would you agree with blowing something up, or worse? My complaint about The Ghosts of Eden Park is that not only do none of the people Abbott talks about seem to care very deeply about these problems – Abbott herself, or at least her book, also does not engage with them. In her book, the story is everything, and it’s actually a pretty cheap and lurid one. Maybe this is not so different, really, from the standards I apply to fiction: I have always found it (pace Oscar Wilde) important to be earnest, at least where matters of moral weight are involved. If you’d asked me on March 13 of this year (the last “regular” day before we were all locked down!) whether I ordinarily spent a lot of time working at my computer, I would have said “Yes!” without hesitation. It turns out, however, that I used to greatly underestimate the amount of time I spent away from my computer–at least, relative to the balance (or, rather, imbalance) between these two options in my pandemic life. While preparing for class always involved at least some time typing up notes and preparing handouts, worksheets, slides, and other materials, for example, going to class meant gathering up actual books and papers and markers–and sometimes

If you’d asked me on March 13 of this year (the last “regular” day before we were all locked down!) whether I ordinarily spent a lot of time working at my computer, I would have said “Yes!” without hesitation. It turns out, however, that I used to greatly underestimate the amount of time I spent away from my computer–at least, relative to the balance (or, rather, imbalance) between these two options in my pandemic life. While preparing for class always involved at least some time typing up notes and preparing handouts, worksheets, slides, and other materials, for example, going to class meant gathering up actual books and papers and markers–and sometimes But here I am now, ready once again to take stock of how things are going in my classes. And the disconcerting truth is that a third of the way through this strange term, I still don’t really know, because I have no base line for comparison, no past experience to check this one against. I’m working pretty incessantly on one teaching task or another, but I get very little feedback compared to the ongoing opportunity, in face-to-face teaching, to “read the room”–which could, of course, be discouraging if you could tell they weren’t with you, but at least there was some immediacy to that input and enough flexibility to the whole operation to let you change things up, on the fly or more deliberately. One of the most disorienting things about online teaching so far, in fact, is the time lapse: because a lot of materials need to be ready ahead of time, I’m usually working on next week’s lectures and handouts while the students are working on this week’s. (Yes, that gets very confusing sometimes!) If I sense that something isn’t clicking this week, it can be pretty hard to figure out where or how to adapt.

But here I am now, ready once again to take stock of how things are going in my classes. And the disconcerting truth is that a third of the way through this strange term, I still don’t really know, because I have no base line for comparison, no past experience to check this one against. I’m working pretty incessantly on one teaching task or another, but I get very little feedback compared to the ongoing opportunity, in face-to-face teaching, to “read the room”–which could, of course, be discouraging if you could tell they weren’t with you, but at least there was some immediacy to that input and enough flexibility to the whole operation to let you change things up, on the fly or more deliberately. One of the most disorienting things about online teaching so far, in fact, is the time lapse: because a lot of materials need to be ready ahead of time, I’m usually working on next week’s lectures and handouts while the students are working on this week’s. (Yes, that gets very confusing sometimes!) If I sense that something isn’t clicking this week, it can be pretty hard to figure out where or how to adapt. Certainly some parts of this feel easier now than they did at first. The start of term is always chaotic, and this year it was worse than ever before because communicating by writing is just less efficient than talking to people or showing them things directly. (That said, at least when everything is written down there is less chance of details just getting lost or forgotten: the documents are always there for reference! The sheer quantity of written materials becomes its own kind of burden, but there’s still something to be said for having what amounts to a detailed instruction manual for the entire course.) By and large my classes seem to have settled into a rhythm now, though, and as a result the stress has gone down on both sides and the quality of actual work has gone up. It’s clear that the online model is harder for some students who would almost certainly be better off with more external structure and tangible support–but there are also students who find the move away from in-person pressures congenial. At this point I personally feel that, given the option, I would never teach online again: I have not had the transformative experience I’ve heard about from other instructors who ended up wholly converted to this mode of instruction. But it’s early yet, I suppose, and of course right now I don’t have a choice–and in spite of everything, I’m glad about that, as it’s not as if being in the classroom under current circumstances would be a return to the kind of work I loved. I’m also very grateful to have the job security I do, and that, along with my real desire to do the best I can for my students, keeps me pretty motivated and determined to keep trying to do this as well as I can.

Certainly some parts of this feel easier now than they did at first. The start of term is always chaotic, and this year it was worse than ever before because communicating by writing is just less efficient than talking to people or showing them things directly. (That said, at least when everything is written down there is less chance of details just getting lost or forgotten: the documents are always there for reference! The sheer quantity of written materials becomes its own kind of burden, but there’s still something to be said for having what amounts to a detailed instruction manual for the entire course.) By and large my classes seem to have settled into a rhythm now, though, and as a result the stress has gone down on both sides and the quality of actual work has gone up. It’s clear that the online model is harder for some students who would almost certainly be better off with more external structure and tangible support–but there are also students who find the move away from in-person pressures congenial. At this point I personally feel that, given the option, I would never teach online again: I have not had the transformative experience I’ve heard about from other instructors who ended up wholly converted to this mode of instruction. But it’s early yet, I suppose, and of course right now I don’t have a choice–and in spite of everything, I’m glad about that, as it’s not as if being in the classroom under current circumstances would be a return to the kind of work I loved. I’m also very grateful to have the job security I do, and that, along with my real desire to do the best I can for my students, keeps me pretty motivated and determined to keep trying to do this as well as I can. The best thing I can say about my courses right now is that I do finally feel as if I am paying more attention to content than to logistics–which means that when I post about them, I might start talking more about what we’re actually studying in them, like I used to! A trial run: In my intro class (“Literature: How It Works” – a dull title but a pragmatic focus that actually suits my usual approach to first-year classes) we are wrapping up our work on poetry. This week students get to choose a ‘cluster’ of related poems to discuss, hopefully showing off what they have learned about literary devices and poetic form and interpretation so far; then next week we will turn our attention to short stories. I expect a lot of them will like that change of focus; I just hope I can coach them to keep paying attention to details and form and not relax into plot summary.

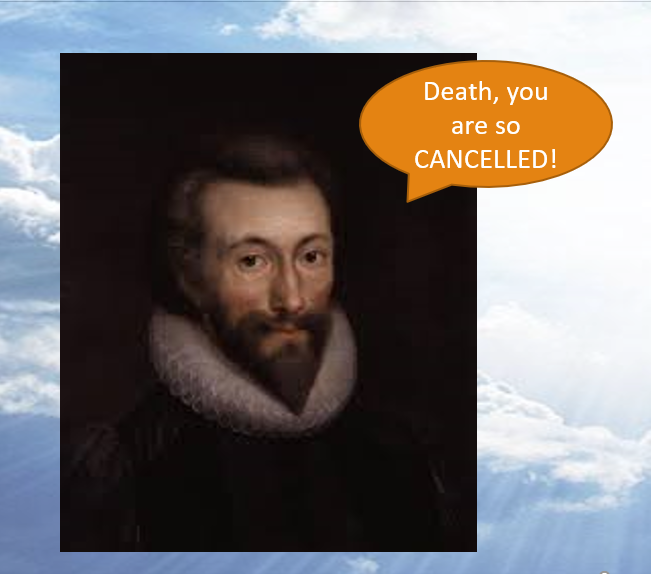

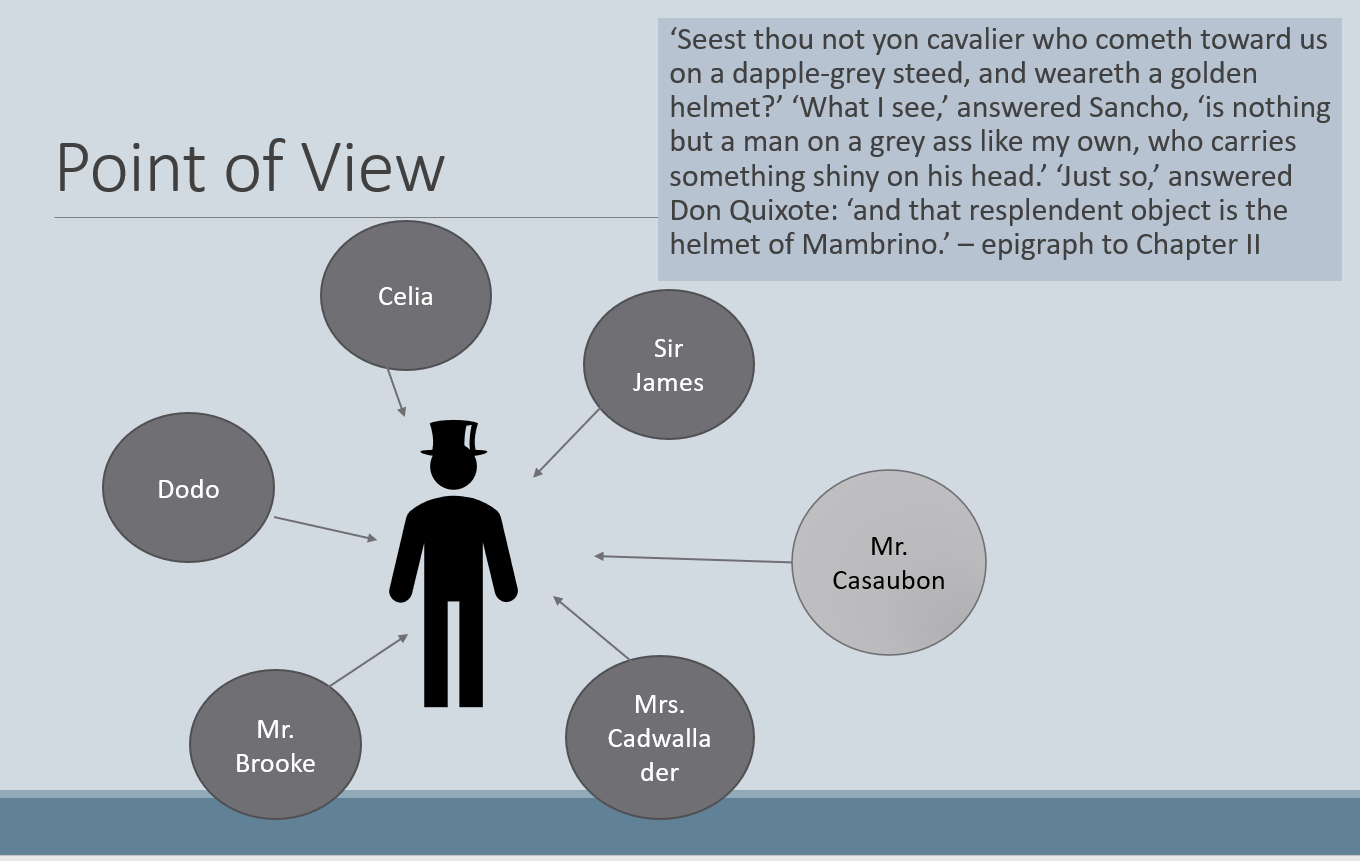

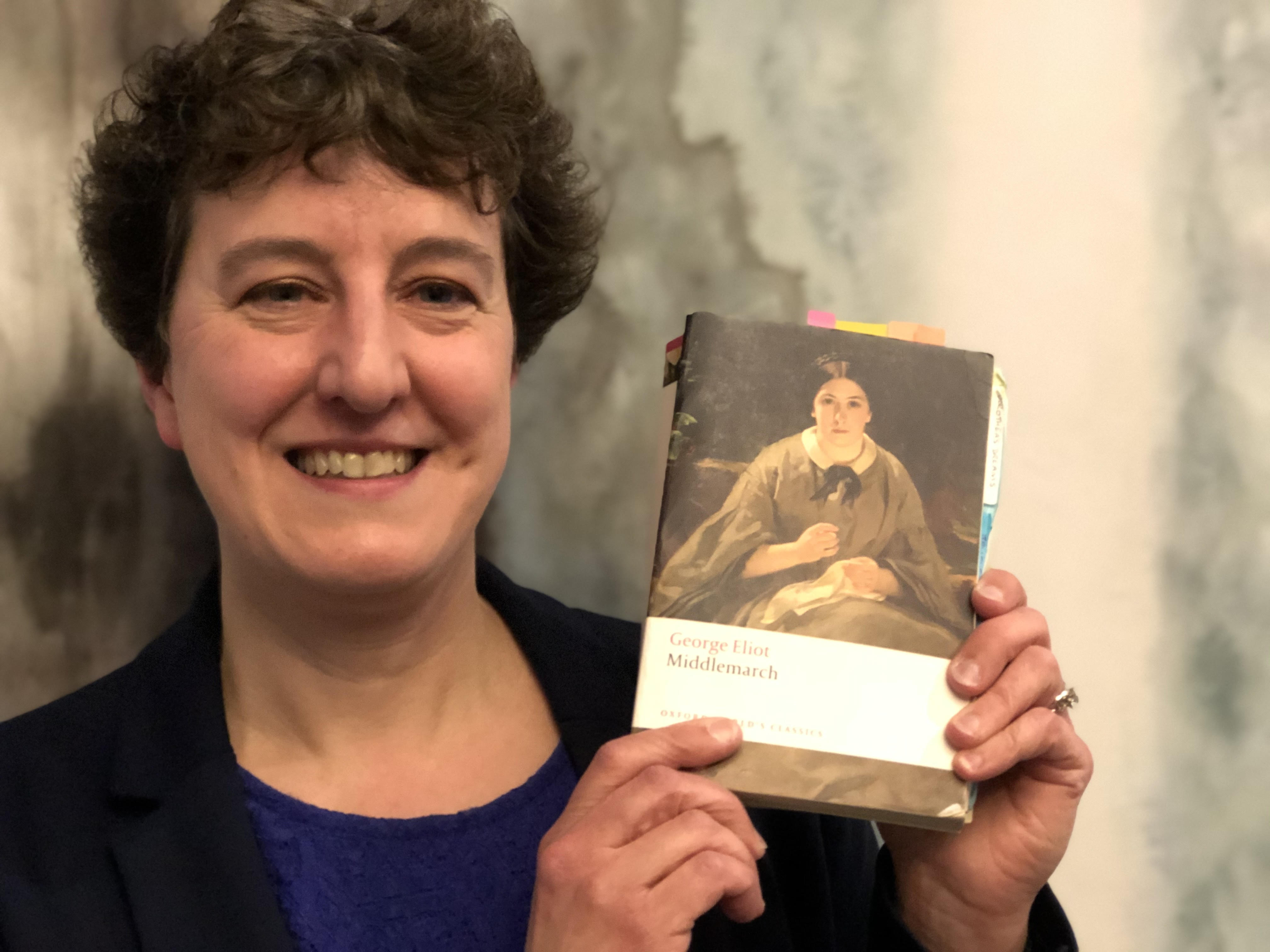

The best thing I can say about my courses right now is that I do finally feel as if I am paying more attention to content than to logistics–which means that when I post about them, I might start talking more about what we’re actually studying in them, like I used to! A trial run: In my intro class (“Literature: How It Works” – a dull title but a pragmatic focus that actually suits my usual approach to first-year classes) we are wrapping up our work on poetry. This week students get to choose a ‘cluster’ of related poems to discuss, hopefully showing off what they have learned about literary devices and poetic form and interpretation so far; then next week we will turn our attention to short stories. I expect a lot of them will like that change of focus; I just hope I can coach them to keep paying attention to details and form and not relax into plot summary. In 19th-Century Fiction we start Middlemarch this week! I, at least, am very excited about this! (Honestly, though: isn’t the cover of the new OWC edition dreadful? They could hardly have made the novel look less fun and inviting. Dorothea is supposed to be blooming, not gloomy!) Rereading the novel and working on my slide presentations to launch our discussions of it has been pretty fun, and also very intellectually challenging, because I have had to make a lot of decisions about how to package the concepts and examples and approaches I would usually lay out over the first few class meetings. While I would certainly do some lecturing in a face-to-face course, I always prefer to draw students towards ideas about how the novel works and what it means through discussion, using a lot of open-ended questions and brainstorming on the white board (where I draw lots of what one of my students [hi, Bea!] recently described as “demented stick figures” 😊). This is hard to reproduce asynchronously!

In 19th-Century Fiction we start Middlemarch this week! I, at least, am very excited about this! (Honestly, though: isn’t the cover of the new OWC edition dreadful? They could hardly have made the novel look less fun and inviting. Dorothea is supposed to be blooming, not gloomy!) Rereading the novel and working on my slide presentations to launch our discussions of it has been pretty fun, and also very intellectually challenging, because I have had to make a lot of decisions about how to package the concepts and examples and approaches I would usually lay out over the first few class meetings. While I would certainly do some lecturing in a face-to-face course, I always prefer to draw students towards ideas about how the novel works and what it means through discussion, using a lot of open-ended questions and brainstorming on the white board (where I draw lots of what one of my students [hi, Bea!] recently described as “demented stick figures” 😊). This is hard to reproduce asynchronously!

I do expect a bit of stuttering as we get going on Middlemarch: my experience of teaching it in the classroom, where I can play ‘cheerleader-in-chief,’ has been that even with me absolutely radiating enthusiasm for it, it can be a hard sell at first, and though I am trying to be as enthusiastic as I can this time too, I have to communicate so much more indirectly that I can’t be sure it will come across, much less be contagious! The stumbling block is usually the amount of exposition, which requires a different kind of attention and patience and can muffle, on a first reading, the sharpness and comedy of the dialogue as well as of the narrator herself. I’m also often surprised by how little students like Dorothea: is idealism so out of fashion these days? But there are always some students who love the book, at first or eventually, and of course my job is not to make them like our readings but to help them learn about them.

I do expect a bit of stuttering as we get going on Middlemarch: my experience of teaching it in the classroom, where I can play ‘cheerleader-in-chief,’ has been that even with me absolutely radiating enthusiasm for it, it can be a hard sell at first, and though I am trying to be as enthusiastic as I can this time too, I have to communicate so much more indirectly that I can’t be sure it will come across, much less be contagious! The stumbling block is usually the amount of exposition, which requires a different kind of attention and patience and can muffle, on a first reading, the sharpness and comedy of the dialogue as well as of the narrator herself. I’m also often surprised by how little students like Dorothea: is idealism so out of fashion these days? But there are always some students who love the book, at first or eventually, and of course my job is not to make them like our readings but to help them learn about them.

We pick up again about a decade later and much has changed. Most importantly, Aren has left his adopted family and is living a bit of a rough life in Halifax. Distressed and frustrated, both on his behalf and her own, Kay comes up with a plan to take him “home” to Pulo Anna. Once more we find ourselves on board ship and traveling across the seas. Although the next part of the book is as carefully and thoughtfully crafted as the first part, as I made my way through it, and even more so at the end of the novel, I found myself preoccupied with what Endicott had left out by not addressing the intervening years: a lot was missing, I thought, that would have illuminated both the action and, more importantly, the meaning, of the novel’s resolution.

We pick up again about a decade later and much has changed. Most importantly, Aren has left his adopted family and is living a bit of a rough life in Halifax. Distressed and frustrated, both on his behalf and her own, Kay comes up with a plan to take him “home” to Pulo Anna. Once more we find ourselves on board ship and traveling across the seas. Although the next part of the book is as carefully and thoughtfully crafted as the first part, as I made my way through it, and even more so at the end of the novel, I found myself preoccupied with what Endicott had left out by not addressing the intervening years: a lot was missing, I thought, that would have illuminated both the action and, more importantly, the meaning, of the novel’s resolution. It has been two weeks since my last post. That sounds almost confessional: forgive me, gentle readers; it has been fourteen days since

It has been two weeks since my last post. That sounds almost confessional: forgive me, gentle readers; it has been fourteen days since  I expressed cautious optimism when the term began and I do still feel some of that, even if at times over the past couple of weeks it has been challenged by fatigue and frustration and sadness. The students are there and most of them are really trying; in my turn, I am doing my level best to demonstrate “instructor presence” and make them feel that I care and am paying attention, not just tracking submissions. I’ve already made a few adjustments to the requirements, too, to reflect what we are all learning about how long all of this takes. Also, although preparing recorded segments is not my favorite thing to do, I find devising topics and shaping them into what seem (to me at least) like engaging little packages intellectually stimulating and even fun sometimes.

I expressed cautious optimism when the term began and I do still feel some of that, even if at times over the past couple of weeks it has been challenged by fatigue and frustration and sadness. The students are there and most of them are really trying; in my turn, I am doing my level best to demonstrate “instructor presence” and make them feel that I care and am paying attention, not just tracking submissions. I’ve already made a few adjustments to the requirements, too, to reflect what we are all learning about how long all of this takes. Also, although preparing recorded segments is not my favorite thing to do, I find devising topics and shaping them into what seem (to me at least) like engaging little packages intellectually stimulating and even fun sometimes.  The readings, too, are as good as they always are, and when I have time to linger over them, that really boosts my morale. I reread the first half of North and South this week (a bit hastily, but still all through) and got excited about the many ways it provokes comparisons with Hard Times, which we are just wrapping up. And in my intro class we are doing Woolf’s “The Death of the Moth,” which was also a tonic to revisit. It’s so beautiful and so sad and so oddly uplifting, in its contemplation of

The readings, too, are as good as they always are, and when I have time to linger over them, that really boosts my morale. I reread the first half of North and South this week (a bit hastily, but still all through) and got excited about the many ways it provokes comparisons with Hard Times, which we are just wrapping up. And in my intro class we are doing Woolf’s “The Death of the Moth,” which was also a tonic to revisit. It’s so beautiful and so sad and so oddly uplifting, in its contemplation of It is hard to know how to begin the 2020-21 iteration of

It is hard to know how to begin the 2020-21 iteration of  So how is it going? One of the oddest things about it, to be honest, is that I really have no idea. The whole past week felt like a massive anti-climax: after months of work, trying to re-train myself and take on board an overwhelming amount of information about “best practices” for online course design and student engagement and teacher presence, after taking a 9-week online course myself to learn about how to do this, after countless hours revising my course outlines and schedules and learning new tools and building my actual Brightspace course sites … all with September 8 as the looming deadline for when the students would “arrive” and the whole experiment would really begin … After all of this, there was no one moment when we were back in class, no online equivalent to that exhilarating and terrifying first face to face session. Instead, because this is how asynchronous online teaching works, students just gradually and on their own timeline started checking in and making their first contributions, while I watched and waited and wondered and tried not to pounce too fast whenever a new notification appeared.

So how is it going? One of the oddest things about it, to be honest, is that I really have no idea. The whole past week felt like a massive anti-climax: after months of work, trying to re-train myself and take on board an overwhelming amount of information about “best practices” for online course design and student engagement and teacher presence, after taking a 9-week online course myself to learn about how to do this, after countless hours revising my course outlines and schedules and learning new tools and building my actual Brightspace course sites … all with September 8 as the looming deadline for when the students would “arrive” and the whole experiment would really begin … After all of this, there was no one moment when we were back in class, no online equivalent to that exhilarating and terrifying first face to face session. Instead, because this is how asynchronous online teaching works, students just gradually and on their own timeline started checking in and making their first contributions, while I watched and waited and wondered and tried not to pounce too fast whenever a new notification appeared.

I’m also genuinely pleased about the contributions that have come in, especially, in both courses, the introductions students have been posting on our “getting to know each other” discussion boards. As I said to them, our first crucial task is to begin building the class into a community, and it has been lovely to see them embrace that goal by telling us a little bit about themselves and then (best of all) responding with great friendliness to each other. I don’t usually solicit individual introductions in all of my F2F classes, only in the smaller seminars, so actually I know more about these groups than I think I ever have this early in the term. While a lot of what I read and practiced this summer was about how to make myself present to my students as a real, if virtual, person, this exercise has been great for making them present to me, not just “students” in the abstract but two really varied and interesting groups of people who bring different perspectives, interests, and needs to our collective enterprise.

I’m also genuinely pleased about the contributions that have come in, especially, in both courses, the introductions students have been posting on our “getting to know each other” discussion boards. As I said to them, our first crucial task is to begin building the class into a community, and it has been lovely to see them embrace that goal by telling us a little bit about themselves and then (best of all) responding with great friendliness to each other. I don’t usually solicit individual introductions in all of my F2F classes, only in the smaller seminars, so actually I know more about these groups than I think I ever have this early in the term. While a lot of what I read and practiced this summer was about how to make myself present to my students as a real, if virtual, person, this exercise has been great for making them present to me, not just “students” in the abstract but two really varied and interesting groups of people who bring different perspectives, interests, and needs to our collective enterprise. Still, I find the spread of the experience out over all hours of the day and all the days of the week disorienting, destabilizing, uncomfortable. Usually my weekly schedule involves regular build-ups to each class meeting: preparing notes and materials and ideas and plans, doing the reading, summoning the energy. Then there’s the live session, which in the moment absorbs all my concentration. When it’s over, I’m drained, even if (especially if!) there has been a really good, lively discussion: being in the moment for that kind of exchange is unlike anything else I do in terms of how focused but also flexible, how attentive to others but also on-task I need to be. I love it, and I really miss it already. I know we can have engaged and intellectually serious exchanges in our online format, but they won’t have the same rhythm, or perhaps any rhythm at all, who knows. Not having to be up and dressed and out the door early in the morning (or ever!) is some compensation, and I expect I will find more of a routine as we settle into the term, but (and I expect I’m going to be saying things like this a lot this term, so sorry for the repetition) it’s a strange new way of being a professor.

Still, I find the spread of the experience out over all hours of the day and all the days of the week disorienting, destabilizing, uncomfortable. Usually my weekly schedule involves regular build-ups to each class meeting: preparing notes and materials and ideas and plans, doing the reading, summoning the energy. Then there’s the live session, which in the moment absorbs all my concentration. When it’s over, I’m drained, even if (especially if!) there has been a really good, lively discussion: being in the moment for that kind of exchange is unlike anything else I do in terms of how focused but also flexible, how attentive to others but also on-task I need to be. I love it, and I really miss it already. I know we can have engaged and intellectually serious exchanges in our online format, but they won’t have the same rhythm, or perhaps any rhythm at all, who knows. Not having to be up and dressed and out the door early in the morning (or ever!) is some compensation, and I expect I will find more of a routine as we settle into the term, but (and I expect I’m going to be saying things like this a lot this term, so sorry for the repetition) it’s a strange new way of being a professor. As for specifics, well, we’re discussing Seamus Heaney’s “Digging” and Adrienne Rich’s “Aunt Jennifer’s Tiger” in my intro class this coming week, and in 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Hard Times (which I assigned this term because we ended up cutting it last term when we ‘pivoted’ to online). These are all texts I like a lot, though in my experience Hard Times is often a hard sell, even to students who otherwise like Dickens (which is never all of them, of course). Will I be able to communicate my enthusiasm and generate the kinds of discussions I aspire to in the classroom without being in the classroom? I guess I’ll find out. I’m trying to create recorded lectures that open up into writing prompts, rather than drawing conclusions, much as I would move in the classroom through laying out some ideas, contexts, or questions and then opening things up to their input. I am actually having some fun with this, though yet one more unknown is how effective my first attempts will be. I have the next two weeks of material nearly completed, so that buys me a bit of time: as I see what works and what doesn’t, and which approach to the lectures they prefer, I can adapt the next round accordingly.

As for specifics, well, we’re discussing Seamus Heaney’s “Digging” and Adrienne Rich’s “Aunt Jennifer’s Tiger” in my intro class this coming week, and in 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Hard Times (which I assigned this term because we ended up cutting it last term when we ‘pivoted’ to online). These are all texts I like a lot, though in my experience Hard Times is often a hard sell, even to students who otherwise like Dickens (which is never all of them, of course). Will I be able to communicate my enthusiasm and generate the kinds of discussions I aspire to in the classroom without being in the classroom? I guess I’ll find out. I’m trying to create recorded lectures that open up into writing prompts, rather than drawing conclusions, much as I would move in the classroom through laying out some ideas, contexts, or questions and then opening things up to their input. I am actually having some fun with this, though yet one more unknown is how effective my first attempts will be. I have the next two weeks of material nearly completed, so that buys me a bit of time: as I see what works and what doesn’t, and which approach to the lectures they prefer, I can adapt the next round accordingly.

Where Mrs. Browning saw, he smelt; where she wrote, he snuffed.

Where Mrs. Browning saw, he smelt; where she wrote, he snuffed. And this brings me to the other thing I really liked about Flush, which is the clever way Woolf conveys the daring and intensity of the romance between EBB and Robert Browning. Flush is keenly sensitive to changes in his mistress’s mood and the progress of her feelings for Browning – from keen but uncertain interest to expanding confidence to love – is beautifully conveyed through Flush’s peripheral and often peevish point of view:

And this brings me to the other thing I really liked about Flush, which is the clever way Woolf conveys the daring and intensity of the romance between EBB and Robert Browning. Flush is keenly sensitive to changes in his mistress’s mood and the progress of her feelings for Browning – from keen but uncertain interest to expanding confidence to love – is beautifully conveyed through Flush’s peripheral and often peevish point of view:

Rooney actually took at least two big risks in taking on this particular subject–or, in taking it on the way she did. The first is the obvious one: a pigeon narrator! But I think this leap of imaginative faith was necessary to mitigate the second risk, which is telling yet another story of bravery and brotherhood in the trenches. To some extent Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey is exactly that kind of book, and this literary ground is so well-trodden that even the best new treatments can seem clichéd (and

Rooney actually took at least two big risks in taking on this particular subject–or, in taking it on the way she did. The first is the obvious one: a pigeon narrator! But I think this leap of imaginative faith was necessary to mitigate the second risk, which is telling yet another story of bravery and brotherhood in the trenches. To some extent Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey is exactly that kind of book, and this literary ground is so well-trodden that even the best new treatments can seem clichéd (and  This is a structural reflection of Rooney’s commitment to equivalence between her human and her animal protagonists, and by the end that equivalence seemed to be the real point of the novel. It’s making the case against speciesism; it pushes us repeatedly to consider why we (including novelists) typically treat animals as accessories to human stories if we consider them at all, rather than accepting that they have their own whole, intrinsically meaningful lives and perspectives. “I think of these numbers still all the time,” says Cher Ami as she reflects on the devastating human casualties on the front; but also,

This is a structural reflection of Rooney’s commitment to equivalence between her human and her animal protagonists, and by the end that equivalence seemed to be the real point of the novel. It’s making the case against speciesism; it pushes us repeatedly to consider why we (including novelists) typically treat animals as accessories to human stories if we consider them at all, rather than accepting that they have their own whole, intrinsically meaningful lives and perspectives. “I think of these numbers still all the time,” says Cher Ami as she reflects on the devastating human casualties on the front; but also, That said, her whole approach is a flamboyant adventure in anthropomorphism: if I were inclined to be critical about the book, I might start there, with the idea that the best way to earn our respect for animals is to depict them as essentially human-like. For all the specific references to pigeon behaviors and preferences, Cher Ami doesn’t really seem much more bird-like in her consciousness than Margalo in Stuart Little 2. I also got a bit tired of Rooney’s using her as a device for social commentary and criticism: for a stuffed bird, Cher Ami gets pretty preachy about racism and sexism and militarism. Those were the moments when my own commitment to Rooney’s experiment got the most wobbly. In contrast, my engagement with Charles Whittlesey never wavered. The sad story of his inability to recover from what he saw and did in “the Pocket” during those terrifying days–the very things that, to others, made him a hero–is a more powerful critique of war and the cynicism of its leaders and promoters than any of Cher Ami’s more didactic remarks.

That said, her whole approach is a flamboyant adventure in anthropomorphism: if I were inclined to be critical about the book, I might start there, with the idea that the best way to earn our respect for animals is to depict them as essentially human-like. For all the specific references to pigeon behaviors and preferences, Cher Ami doesn’t really seem much more bird-like in her consciousness than Margalo in Stuart Little 2. I also got a bit tired of Rooney’s using her as a device for social commentary and criticism: for a stuffed bird, Cher Ami gets pretty preachy about racism and sexism and militarism. Those were the moments when my own commitment to Rooney’s experiment got the most wobbly. In contrast, my engagement with Charles Whittlesey never wavered. The sad story of his inability to recover from what he saw and did in “the Pocket” during those terrifying days–the very things that, to others, made him a hero–is a more powerful critique of war and the cynicism of its leaders and promoters than any of Cher Ami’s more didactic remarks. The other World War I novel Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey most reminded me of was Timothy Findley’s The Wars, because there too it is animals who force a moral reckoning. Findley does not go as far as Rooney in addressing the animals’ own perspectives: in fact, it’s their inability to speak or act for themselves that arouses Robert Ross’s rage and, ultimately, rebellion. The horses are provocations for his crisis of conscience, not meaningful agents in themselves. The affinity between the two novels lies in their aversion to the human arrogance that subordinates other living creatures to our often highly destructive priorities. World War I is often talked about as particularly tragic because its losses served no higher purpose. “The defeat of Hitler and company,” as Cher Ami remarks,

The other World War I novel Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey most reminded me of was Timothy Findley’s The Wars, because there too it is animals who force a moral reckoning. Findley does not go as far as Rooney in addressing the animals’ own perspectives: in fact, it’s their inability to speak or act for themselves that arouses Robert Ross’s rage and, ultimately, rebellion. The horses are provocations for his crisis of conscience, not meaningful agents in themselves. The affinity between the two novels lies in their aversion to the human arrogance that subordinates other living creatures to our often highly destructive priorities. World War I is often talked about as particularly tragic because its losses served no higher purpose. “The defeat of Hitler and company,” as Cher Ami remarks,