I’m having a hard time keeping track of what day it is, mostly because under the new work-from-home protocol–and the more general stay-at-home order–there’s not much difference between one day and the next. I’ve also stopped doing grocery shopping on Saturday mornings (which had been my routine for more than two decades): now I go mid-week, usually Wednesday, as early as I’m allowed in the store, which means I’m home by 9 a.m. and so, aside from the gradually receding adrenaline from the stress of the outing, it too then becomes a day like every other day.

I’m having a hard time keeping track of what day it is, mostly because under the new work-from-home protocol–and the more general stay-at-home order–there’s not much difference between one day and the next. I’ve also stopped doing grocery shopping on Saturday mornings (which had been my routine for more than two decades): now I go mid-week, usually Wednesday, as early as I’m allowed in the store, which means I’m home by 9 a.m. and so, aside from the gradually receding adrenaline from the stress of the outing, it too then becomes a day like every other day.

As these days become weeks and months, I am trying to find a rhythm that brings a bit of order to the passing hours without adding unnecessary pressure, something in between just drifting and trying to enforce a fixed schedule when really there’s no need as long as, bit by bit, the things that need doing get done. Most mornings I spend puttering way on online teaching: reading, experimenting with tools in Brightspace, trying to imagine how else to do what I’ve always done, working through the modules for the online course I signed up for on online course design. Being a student in this course is probably as valuable as anything they are directly teaching me about online learning: I feel first-hand, for example, the importance of engagement, or the discouragement of its lack–so many people enrolled, so few people contributing to any of the discussion boards! I’m trying hard to sustain my positive attitude, or at least to stay practical about what lies ahead even if sometimes my heart just sinks when I think about it or I get swamped with doubt about my ability to do a good job, to make the experience anything like what I think it should be and hope, on my better days, that it can be.

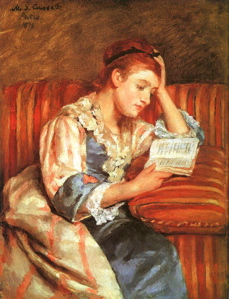

Afternoons are (more or less) for reading. I haven’t posted about any books since The Glass Hotel but that isn’t because I haven’t read any. In fact, I have read four (almost five) books since then, all by P. D. James, because I am rereading her complete works (or all of her mysteries, at any rate) in preparation for writing a piece for the TLS in honor of her centenary. I was really glad that the editors liked this idea: it’s a perfect project for this haphazard summer. I have a lot of ideas about James from having read (and taught) her for years, but I have not had a reason to put those ideas in good order before, and it has also been a long time since I read most of her back catalog. It’s very interesting reading through the books all at once and in order: you quickly notice recurring themes and habits, strengths and weaknesses, and also the way her scope and themes expand. I think (I hope!) that this is a kind of essay I’m reasonably good at, collating and synthesizing across a range of examples; this is also an approach that I think works well for crime series, which are interesting both in their individual parts and as enduring creations that are more than the sum of those parts, often (as in this case) through the story they tell about the central detective that unifies them. My previous essays on Dick Francis and the Martin Beck books were in a similar vein. I won’t want to anticipate too much of the final product here, but I will probably report back occasionally, partly to keep holding myself accountable! Maybe when I’ve finished my reread I should do another ranked list. My post on the top 10 Dick Francis novels has been my most-read post of all time! 🙂

Afternoons are (more or less) for reading. I haven’t posted about any books since The Glass Hotel but that isn’t because I haven’t read any. In fact, I have read four (almost five) books since then, all by P. D. James, because I am rereading her complete works (or all of her mysteries, at any rate) in preparation for writing a piece for the TLS in honor of her centenary. I was really glad that the editors liked this idea: it’s a perfect project for this haphazard summer. I have a lot of ideas about James from having read (and taught) her for years, but I have not had a reason to put those ideas in good order before, and it has also been a long time since I read most of her back catalog. It’s very interesting reading through the books all at once and in order: you quickly notice recurring themes and habits, strengths and weaknesses, and also the way her scope and themes expand. I think (I hope!) that this is a kind of essay I’m reasonably good at, collating and synthesizing across a range of examples; this is also an approach that I think works well for crime series, which are interesting both in their individual parts and as enduring creations that are more than the sum of those parts, often (as in this case) through the story they tell about the central detective that unifies them. My previous essays on Dick Francis and the Martin Beck books were in a similar vein. I won’t want to anticipate too much of the final product here, but I will probably report back occasionally, partly to keep holding myself accountable! Maybe when I’ve finished my reread I should do another ranked list. My post on the top 10 Dick Francis novels has been my most-read post of all time! 🙂

I do have some other books on the go or in the queue. I am about 100 pages into Andrew Miller’s The Crossing, which is the last of the random pile of library books I brought home shortly before the lockdown. It’s good so far in the way his other books were good: meticulous, quietly and a bit ominously atmospheric. I ordered Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian from Bookmark, and it looks very tempting; I pulled Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts from the shelf because I’ve never read it and if there was ever a time to travel vicariously in excellent literary company, this is surely it. My book club “met” on Thursday to discuss Detective Inspector Huss (mixed feelings all round) and there too the idea of being mentally somewhere else appeals: Turkey somehow came up as a preferred destination, so we may do something by Elif Shafak next. I am still struggling a bit with concentration, so although I have John Le Carre’s A Perfect Spy still to read from my Christmas stash, I think now may not be the time for something intricately plotted. On the other hand, maybe now is exactly the time for a book that will insist I really pay attention!

I do have some other books on the go or in the queue. I am about 100 pages into Andrew Miller’s The Crossing, which is the last of the random pile of library books I brought home shortly before the lockdown. It’s good so far in the way his other books were good: meticulous, quietly and a bit ominously atmospheric. I ordered Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian from Bookmark, and it looks very tempting; I pulled Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts from the shelf because I’ve never read it and if there was ever a time to travel vicariously in excellent literary company, this is surely it. My book club “met” on Thursday to discuss Detective Inspector Huss (mixed feelings all round) and there too the idea of being mentally somewhere else appeals: Turkey somehow came up as a preferred destination, so we may do something by Elif Shafak next. I am still struggling a bit with concentration, so although I have John Le Carre’s A Perfect Spy still to read from my Christmas stash, I think now may not be the time for something intricately plotted. On the other hand, maybe now is exactly the time for a book that will insist I really pay attention!

We have certainly been watching a lot of TV: the new season of Better Call Saul, The End of the F***ing World, Little Fires Everywhere, The Stranger, Ozark … If we’d known what lay ahead, we might have rationed some of the other shows we watched over the winter–season 5 of Line of Duty, the latest season of Shetland–that we knew to be engrossing. It is a good time to be watching Parks and Recreation for the first time: its gentle, goodhearted humor is a tonic. Sadly, the channel that carried the Great British Sewing Bee and various other painting and craft shows has dropped suddenly from our cable package, just when such low-key distractions would be more welcome than ever, and a lot of the videos on the Youtube channel where I had found the Great Pottery Throwdown are now blocked, which I guess is legitimate but it’s still sad. It was March 8 that I wrote about how “gripped and soothed” I was by shows highlighting creativity and making things: little did I know that would be the last blog post of the Before Times.

We have certainly been watching a lot of TV: the new season of Better Call Saul, The End of the F***ing World, Little Fires Everywhere, The Stranger, Ozark … If we’d known what lay ahead, we might have rationed some of the other shows we watched over the winter–season 5 of Line of Duty, the latest season of Shetland–that we knew to be engrossing. It is a good time to be watching Parks and Recreation for the first time: its gentle, goodhearted humor is a tonic. Sadly, the channel that carried the Great British Sewing Bee and various other painting and craft shows has dropped suddenly from our cable package, just when such low-key distractions would be more welcome than ever, and a lot of the videos on the Youtube channel where I had found the Great Pottery Throwdown are now blocked, which I guess is legitimate but it’s still sad. It was March 8 that I wrote about how “gripped and soothed” I was by shows highlighting creativity and making things: little did I know that would be the last blog post of the Before Times.

So that’s how my week is going–how my weeks are going, as they blur together, weirdly ephemeral and indistinct but also somehow relentless, a foggy procession through time. I continue to be really grateful for Twitter and blogs: reading and talking about reading and knowing that the rest of you are out there too, all of us getting by as best we can and hanging on to the things we care about, including books and ideas and each other.

I’m not sure whether I’m surprised that it has already been three weeks since we began extreme social distancing here or surprised that it hasn’t been even longer — normalcy itself seems so distant now! It seems remote in both directions, too: hard as it is to think back on the relative simplicity of ordinary life before, it is even harder to look ahead because there is so much uncertainty about when and how those conditions will return. That’s as good an argument as any for trying to take this massive disruption one day at a time, which is certainly what I have been trying to do. My success varies, as does my ability to get through each day with anything like the (again, relative) equanimity and focus I used to have.

I’m not sure whether I’m surprised that it has already been three weeks since we began extreme social distancing here or surprised that it hasn’t been even longer — normalcy itself seems so distant now! It seems remote in both directions, too: hard as it is to think back on the relative simplicity of ordinary life before, it is even harder to look ahead because there is so much uncertainty about when and how those conditions will return. That’s as good an argument as any for trying to take this massive disruption one day at a time, which is certainly what I have been trying to do. My success varies, as does my ability to get through each day with anything like the (again, relative) equanimity and focus I used to have.

Like everyone else in the world (and how odd for that not to be hyperbole, though our timelines have differed) I have spent the past week adjusting to the unprecedented risks and disruptions created by the spread of COVID-19. Friday March 13 began as a more or less ordinary day of classes: the cloud was looming on the horizon, reports were coming in of the first university closures in Canada, and we had been instructed to start making contingency plans in case Dalhousie followed suit. But my schedule that day was normal almost to the end: I had a meeting with our Associate Dean Academic to discuss my interest in trying contract grading in my first-year writing class; I taught the second of four planned classes on Three Guineas in the Brit Lit survey class and of four planned classes on Mary Barton in 19th-Century British Fiction. The only real break from routine was a brisk walk down to Spring Garden Road at lunch time to pick up a couple of items I thought it might be nice to have secured, just in case: Helene Tursten’s An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good for my book club, which I knew had just come in at Bookmark, and a bottle of my favorite Body Shop shower gel (

Like everyone else in the world (and how odd for that not to be hyperbole, though our timelines have differed) I have spent the past week adjusting to the unprecedented risks and disruptions created by the spread of COVID-19. Friday March 13 began as a more or less ordinary day of classes: the cloud was looming on the horizon, reports were coming in of the first university closures in Canada, and we had been instructed to start making contingency plans in case Dalhousie followed suit. But my schedule that day was normal almost to the end: I had a meeting with our Associate Dean Academic to discuss my interest in trying contract grading in my first-year writing class; I taught the second of four planned classes on Three Guineas in the Brit Lit survey class and of four planned classes on Mary Barton in 19th-Century British Fiction. The only real break from routine was a brisk walk down to Spring Garden Road at lunch time to pick up a couple of items I thought it might be nice to have secured, just in case: Helene Tursten’s An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good for my book club, which I knew had just come in at Bookmark, and a bottle of my favorite Body Shop shower gel (

So I packed up and went home–but still, I realized later, without having quite focused on what was happening. For example, I brought home not just the books we were in the middle of but the books that are (were) next on the class schedule, because it still seemed plausible that we would be doing something like actually finishing the courses as originally planned. And I did not bring home a stack of books that it might just be nice to have copies of at home–any of my Victorian novels, for instance. I own around a dozen copies of Middlemarch, and right now every one of them is out of reach! We are still allowed into our building, and I’ve been thinking I should go get one, and maybe some Trollope. I can’t tell if this really makes much sense, though. I mean, it’s not like I don’t have a lot of books to read right here with me, and I also have e-books of a lot of 19th-century novels because when I bought my first Sony e-reader, years ago, part of the deal was a big stack of free classics to go with it. So what if I don’t like reading long books electronically: I could get used to it. It would be a pretty low-risk outing, given that the campus is basically a ghost town at this point, but I think it’s really psychological reassurance I would be seeking, not reading material, and what are the odds that seeing familiar places I can’t really go back to for who knows how long would actually be comforting?

So I packed up and went home–but still, I realized later, without having quite focused on what was happening. For example, I brought home not just the books we were in the middle of but the books that are (were) next on the class schedule, because it still seemed plausible that we would be doing something like actually finishing the courses as originally planned. And I did not bring home a stack of books that it might just be nice to have copies of at home–any of my Victorian novels, for instance. I own around a dozen copies of Middlemarch, and right now every one of them is out of reach! We are still allowed into our building, and I’ve been thinking I should go get one, and maybe some Trollope. I can’t tell if this really makes much sense, though. I mean, it’s not like I don’t have a lot of books to read right here with me, and I also have e-books of a lot of 19th-century novels because when I bought my first Sony e-reader, years ago, part of the deal was a big stack of free classics to go with it. So what if I don’t like reading long books electronically: I could get used to it. It would be a pretty low-risk outing, given that the campus is basically a ghost town at this point, but I think it’s really psychological reassurance I would be seeking, not reading material, and what are the odds that seeing familiar places I can’t really go back to for who knows how long would actually be comforting? Anyway, it quickly became clear that the right strategy (and, to their credit, the one our administrators have been urging) is not to try to replicate electronically all of our plans for the last few weeks of term, including the final exam period, but to smooth students’ paths to completion as best we can: dropping readings and assignments and giving them options including taking the grade they have earned so far but still also allowing another chance to do better in as painless a way as we can think of. I think the options I came up with for my classes are pretty good, in these respects, but it may be that they don’t go far enough, because this is all turning out to be so much harder than it sounded a week ago–and of course however we might (or might not!) be managing, our students have their own specific circumstances which may make even the most “reasonable” alternatives too much. I have been feeling a lot of regret about the books we won’t get to, especially The Remains of the Day, which I was increasingly excited about as the capstone text for the survey class–what a good book to read right after Three Guineas! As for Three Guineas itself, I was so excited about teaching it for the first time. It’s definitely going back on my syllabus the next time it fits the brief. Sigh.

Anyway, it quickly became clear that the right strategy (and, to their credit, the one our administrators have been urging) is not to try to replicate electronically all of our plans for the last few weeks of term, including the final exam period, but to smooth students’ paths to completion as best we can: dropping readings and assignments and giving them options including taking the grade they have earned so far but still also allowing another chance to do better in as painless a way as we can think of. I think the options I came up with for my classes are pretty good, in these respects, but it may be that they don’t go far enough, because this is all turning out to be so much harder than it sounded a week ago–and of course however we might (or might not!) be managing, our students have their own specific circumstances which may make even the most “reasonable” alternatives too much. I have been feeling a lot of regret about the books we won’t get to, especially The Remains of the Day, which I was increasingly excited about as the capstone text for the survey class–what a good book to read right after Three Guineas! As for Three Guineas itself, I was so excited about teaching it for the first time. It’s definitely going back on my syllabus the next time it fits the brief. Sigh. One of the most emotionally painful parts of all of this has been the abrupt severance of personal relationships, which is what teaching is really all about. I have put course materials together to get us to the end of our current texts, but it is much less rewarding scripting them than it is taking my ideas and questions in to meet them with and seeing what comes of our encounter. Sure, it doesn’t always go swimmingly, but that just means you try again, or try something different. I know there are ways to include more personal and “synchronous” interaction (as we’ve quickly learned to label it!) in online teaching, and of course as someone who spends a lot of time online I already believe that you can cultivate meaningful relationships without meeting face to face. There just isn’t time for that now, though, and also the demands those tools put on everyone to be available and attentive at the same time are all wrong for our immediate circumstances. It isn’t just about finding ways to get through the course material together either: there are students I have been working with for years who it turns out I saw in person for maybe the last time that Friday without even knowing it. I have been thinking about them, and about all of my students, so much since that hectic departure from campus and hoping they know how much I have valued our time together and how much I already miss them!

One of the most emotionally painful parts of all of this has been the abrupt severance of personal relationships, which is what teaching is really all about. I have put course materials together to get us to the end of our current texts, but it is much less rewarding scripting them than it is taking my ideas and questions in to meet them with and seeing what comes of our encounter. Sure, it doesn’t always go swimmingly, but that just means you try again, or try something different. I know there are ways to include more personal and “synchronous” interaction (as we’ve quickly learned to label it!) in online teaching, and of course as someone who spends a lot of time online I already believe that you can cultivate meaningful relationships without meeting face to face. There just isn’t time for that now, though, and also the demands those tools put on everyone to be available and attentive at the same time are all wrong for our immediate circumstances. It isn’t just about finding ways to get through the course material together either: there are students I have been working with for years who it turns out I saw in person for maybe the last time that Friday without even knowing it. I have been thinking about them, and about all of my students, so much since that hectic departure from campus and hoping they know how much I have valued our time together and how much I already miss them! And now, I guess, it’s time to settle in to what people keep euphemistically calling “the new normal.” Here in Halifax we are under strong directions for social distancing; I’ve heard rumors that something more rigorous might be coming, in the hope of really flattening that infamous curve. There are lots of wry jokes and memes about readers or introverts or others whose habits and preferences mean they have been “preparing for this moment our whole lives.” We live a pretty quiet life ourselves, so to some extent this is true of us as well (though not of Maddie, who like many young people is going to be very well served by the various ways she and her friends can stay in touch virtually). It’s pretty different having to stay home, though, and also worrying whenever you go out, even if it’s only for essentials. It’s also not spring yet here–I envy my family in Vancouver the softening weather that makes walks and parks and gardens good options. I am grateful, though, that we are comfortable and together and, so far, healthy. I am also glad I did pick up An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good, because I finished reading it this morning and it is a nice bit of twisted fun…about which more soon, I hope!

And now, I guess, it’s time to settle in to what people keep euphemistically calling “the new normal.” Here in Halifax we are under strong directions for social distancing; I’ve heard rumors that something more rigorous might be coming, in the hope of really flattening that infamous curve. There are lots of wry jokes and memes about readers or introverts or others whose habits and preferences mean they have been “preparing for this moment our whole lives.” We live a pretty quiet life ourselves, so to some extent this is true of us as well (though not of Maddie, who like many young people is going to be very well served by the various ways she and her friends can stay in touch virtually). It’s pretty different having to stay home, though, and also worrying whenever you go out, even if it’s only for essentials. It’s also not spring yet here–I envy my family in Vancouver the softening weather that makes walks and parks and gardens good options. I am grateful, though, that we are comfortable and together and, so far, healthy. I am also glad I did pick up An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good, because I finished reading it this morning and it is a nice bit of twisted fun…about which more soon, I hope! Lately I have found myself both gripped and soothed by a particular genre of television, and happily for me there turns out to be a lot of it–in fact, since I brought it up on Twitter I’ve learned of many more options, which means that even at my current rate of consumption I won’t run out for months. The shows I’ve been binge-watching (as much as I can binge-watch anything in this busy time of term!) are all examples of what you might call ‘gamified creativity’: shows in which dedicated amateur practitioners of some art or craft compete through a series of challenges in the hopes of being recognized as the best of the bunch.

Lately I have found myself both gripped and soothed by a particular genre of television, and happily for me there turns out to be a lot of it–in fact, since I brought it up on Twitter I’ve learned of many more options, which means that even at my current rate of consumption I won’t run out for months. The shows I’ve been binge-watching (as much as I can binge-watch anything in this busy time of term!) are all examples of what you might call ‘gamified creativity’: shows in which dedicated amateur practitioners of some art or craft compete through a series of challenges in the hopes of being recognized as the best of the bunch. The well-known Great British Baking Show is one such show; over the past few years I’ve greatly enjoyed both the original series and the Canadian version. I didn’t initially think about it as showcasing creativity because in some ways baking is such a practical and also such a non-negotiable skill: the cake either rises or it doesn’t, the bottom of the pie is either soggy or it isn’t. Watching Blown Away, Next In Fashion, and some of The Great Pottery Throw Down, however, has clarified for me that a big part of the appeal of TGBBS always was the combination of that practicality with ingenious concepts and creative designs and decorations. That’s what these other shows highlight as well: it’s not enough to be able to sew a hem (or a whole jacket), or throw a pot–you also have to come up with a concept for the project and execute it in a way that (if all goes well) sparks both admiration and pleasure. “Fit for function” is an essential standard on the pottery show, but if all your teapot does is pour, it’s not going to

The well-known Great British Baking Show is one such show; over the past few years I’ve greatly enjoyed both the original series and the Canadian version. I didn’t initially think about it as showcasing creativity because in some ways baking is such a practical and also such a non-negotiable skill: the cake either rises or it doesn’t, the bottom of the pie is either soggy or it isn’t. Watching Blown Away, Next In Fashion, and some of The Great Pottery Throw Down, however, has clarified for me that a big part of the appeal of TGBBS always was the combination of that practicality with ingenious concepts and creative designs and decorations. That’s what these other shows highlight as well: it’s not enough to be able to sew a hem (or a whole jacket), or throw a pot–you also have to come up with a concept for the project and execute it in a way that (if all goes well) sparks both admiration and pleasure. “Fit for function” is an essential standard on the pottery show, but if all your teapot does is pour, it’s not going to  I’ve been wondering what it is about these shows (which have been around for years, after all) that is so appealing to me right now. Certainly part of it is that they are not particularly demanding to watch, and also that overall they are quite cheering: the very idiosyncrasy of the participants combined with their shared passion for their craft is just so heartening, so humane, at a time when there seems to be so much anxiety and inhumanity going around. These shows also celebrate qualities that are often devalued in the wider world, including not just creativity but also beauty, originality, and mastery outside the domain of the relentlessly technical and utilitarian. Sure, there’s something artificial about the competitions themselves (must everything be turned into a game show?) but I actually find the judging process fascinating: speaking as someone who recoiled from Elizabeth Gilbert’s “all that matters is that you made anything at all” pitch in

I’ve been wondering what it is about these shows (which have been around for years, after all) that is so appealing to me right now. Certainly part of it is that they are not particularly demanding to watch, and also that overall they are quite cheering: the very idiosyncrasy of the participants combined with their shared passion for their craft is just so heartening, so humane, at a time when there seems to be so much anxiety and inhumanity going around. These shows also celebrate qualities that are often devalued in the wider world, including not just creativity but also beauty, originality, and mastery outside the domain of the relentlessly technical and utilitarian. Sure, there’s something artificial about the competitions themselves (must everything be turned into a game show?) but I actually find the judging process fascinating: speaking as someone who recoiled from Elizabeth Gilbert’s “all that matters is that you made anything at all” pitch in  I think too that I am engaged by these shows because I have been feeling restless in my own work. What I feel, often, watching the participants demonstrate their plans and then do their best to carry them out, is envy. I think it must be wonderful to be able to do the things they can do–and also to be passionate about doing them, so much so that you never question why you are doing them and are happy to keep trying and trying and trying again to do them better. I especially envy the leap of imagination that takes them from “here’s the task” to “here’s my idea for that task”: bread that looks like a lion, a toilet that looks like a turtle. (That turtle toilet filled me with such irrational joy when it turned out so well! Who would ever think of such a thing? Who would ever make it? And yet isn’t it just delightful?) By comparison, my relationship with my own work is often much more uncertain, and the work itself–whether it’s teaching, grading, researching, or reviewing–doesn’t really feel creative, or at any rate it doesn’t really satisfy my vague desire to be creating something. That’s one reason I took

I think too that I am engaged by these shows because I have been feeling restless in my own work. What I feel, often, watching the participants demonstrate their plans and then do their best to carry them out, is envy. I think it must be wonderful to be able to do the things they can do–and also to be passionate about doing them, so much so that you never question why you are doing them and are happy to keep trying and trying and trying again to do them better. I especially envy the leap of imagination that takes them from “here’s the task” to “here’s my idea for that task”: bread that looks like a lion, a toilet that looks like a turtle. (That turtle toilet filled me with such irrational joy when it turned out so well! Who would ever think of such a thing? Who would ever make it? And yet isn’t it just delightful?) By comparison, my relationship with my own work is often much more uncertain, and the work itself–whether it’s teaching, grading, researching, or reviewing–doesn’t really feel creative, or at any rate it doesn’t really satisfy my vague desire to be creating something. That’s one reason I took  And yet there are creative aspects to my job. As I was starting to write this post, for example, I was also working on my class notes for some new (to me) material I’m teaching next week, including Woolf’s “Kew Gardens” and Three Guineas, both of which I’ve read before, of course, but which I’ve never assigned. This means that I have to come up with a teaching strategy for them, which means figuring out what story I’m going to tell about them: where I’ll begin, what background exposition I’ll include, what plot (for want of a better term) I’ll try to shape our experience of them into. I also think of book reviewing as a kind of storytelling: what might look to a reader of the review “just” like a bit of plot summary, for example, is actually a highly selective retrofitting of the book’s own elements in order to tell my story of what the book is about. The hardest part of writing every review is spotting that story and figuring out how to tell it (and one of the freedoms I most enjoy when writing blog posts, by comparison, is being able to discover it as I go along rather than having to shape the piece around it from the beginning).

And yet there are creative aspects to my job. As I was starting to write this post, for example, I was also working on my class notes for some new (to me) material I’m teaching next week, including Woolf’s “Kew Gardens” and Three Guineas, both of which I’ve read before, of course, but which I’ve never assigned. This means that I have to come up with a teaching strategy for them, which means figuring out what story I’m going to tell about them: where I’ll begin, what background exposition I’ll include, what plot (for want of a better term) I’ll try to shape our experience of them into. I also think of book reviewing as a kind of storytelling: what might look to a reader of the review “just” like a bit of plot summary, for example, is actually a highly selective retrofitting of the book’s own elements in order to tell my story of what the book is about. The hardest part of writing every review is spotting that story and figuring out how to tell it (and one of the freedoms I most enjoy when writing blog posts, by comparison, is being able to discover it as I go along rather than having to shape the piece around it from the beginning). Is it because the building blocks of these particular processes are someone else’s stories that, for all the pleasures they really can offer, they don’t quite satisfy the craving for creativity in my own life, the underlying hunger for it that I am feeding with the vicarious experience of it offered through these shows? Perhaps. So what to do about that? I don’t particularly want to change up my approach to either criticism or teaching: I don’t much like criticism that crowds out its real subject (as I see it) with too much other stuff, and though I know my approach to teaching isn’t the only one (I have colleagues, for instance, who incorporate creative writing and other activities into their classes), it is one I believe in and feel comfortable with. I do have some hobbies–crochet and quilting–that give me the satisfaction of actually creating something, but it’s interesting that they are both (for me, anyway, at my limited skill level) pattern-following crafts; my self-expression in both is limited to choosing a pattern and choosing the materials. That’s not nothing, of course! (Also, crochet in particular is perfect to do while watching TV shows of other people making amazingly creative things. 😊)

Is it because the building blocks of these particular processes are someone else’s stories that, for all the pleasures they really can offer, they don’t quite satisfy the craving for creativity in my own life, the underlying hunger for it that I am feeding with the vicarious experience of it offered through these shows? Perhaps. So what to do about that? I don’t particularly want to change up my approach to either criticism or teaching: I don’t much like criticism that crowds out its real subject (as I see it) with too much other stuff, and though I know my approach to teaching isn’t the only one (I have colleagues, for instance, who incorporate creative writing and other activities into their classes), it is one I believe in and feel comfortable with. I do have some hobbies–crochet and quilting–that give me the satisfaction of actually creating something, but it’s interesting that they are both (for me, anyway, at my limited skill level) pattern-following crafts; my self-expression in both is limited to choosing a pattern and choosing the materials. That’s not nothing, of course! (Also, crochet in particular is perfect to do while watching TV shows of other people making amazingly creative things. 😊) My

My  I thought it might help to write for some places that do run longer pieces, so I wrote a review “on spec” for one such venue but they didn’t want it–in the end it maybe wasn’t a great fit with the place I sent it, although the book I chose (

I thought it might help to write for some places that do run longer pieces, so I wrote a review “on spec” for one such venue but they didn’t want it–in the end it maybe wasn’t a great fit with the place I sent it, although the book I chose ( This is why I keep returning to class prep! It’s so straightforward, and after all, it does have to get done. Maybe I should think of it this way: the better prepared I am for the term, the more likely it is that I can keep working on some kind of writing project even after classes start. My colleagues and I often talk about the way teaching expands to fill however much time you can (or are willing to) give it: this is something we advise TAs and junior colleagues to guard against. Good, detailed course planning is part of a strategy for achieving better balance between my various professional obligations; it’s not just a diversionary tactic when your other commitments are getting you down. Right? RIGHT?!

This is why I keep returning to class prep! It’s so straightforward, and after all, it does have to get done. Maybe I should think of it this way: the better prepared I am for the term, the more likely it is that I can keep working on some kind of writing project even after classes start. My colleagues and I often talk about the way teaching expands to fill however much time you can (or are willing to) give it: this is something we advise TAs and junior colleagues to guard against. Good, detailed course planning is part of a strategy for achieving better balance between my various professional obligations; it’s not just a diversionary tactic when your other commitments are getting you down. Right? RIGHT?! The

The

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

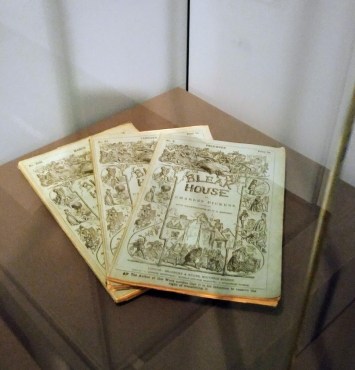

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon.

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon. Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

That’s all still in the future, though, and in the meantime Maddie has exams to get through and I have a bit more time on my sabbatical to make the best use of that I can. Now that everyone else is also done teaching, being on leave feels a bit less special, but I remind myself that May typically fills up with administrative commitments, so I can still enjoy not being part of that. I will write up a post soon reflecting on my sabbatical so far. Before too much longer, I may also actually finish reading a book, and then I can post about that too! I have three in progress: The Break, which I am rereading for my book club, Lissa Evans’s Old Baggage, which I am enjoying so far, and Lucy Parker’s The Austen Playbook which to be honest I am not really loving. I am not currently reading anything on assignment for a review: I’m not sure if that’s good or bad! (It does mean I’m available, if any editors are reading this…)

That’s all still in the future, though, and in the meantime Maddie has exams to get through and I have a bit more time on my sabbatical to make the best use of that I can. Now that everyone else is also done teaching, being on leave feels a bit less special, but I remind myself that May typically fills up with administrative commitments, so I can still enjoy not being part of that. I will write up a post soon reflecting on my sabbatical so far. Before too much longer, I may also actually finish reading a book, and then I can post about that too! I have three in progress: The Break, which I am rereading for my book club, Lissa Evans’s Old Baggage, which I am enjoying so far, and Lucy Parker’s The Austen Playbook which to be honest I am not really loving. I am not currently reading anything on assignment for a review: I’m not sure if that’s good or bad! (It does mean I’m available, if any editors are reading this…)

I’m not quite ready for my traditional posts about what I’ve read and written in the past year: for one thing, I often read at least one really great book between Christmas and New Year’s, when the holiday bustle has ended and the book-shaped packages under the tree have revealed their secrets! (In fact, I’m currently reading Emily Wilson’s translation of the Odyssey, which seems a likely contender for any “best of 2018” list.) That doesn’t mean, though, that I’m not looking back over 2018 and ahead to 2019, trying to figure out where I’ve been, where I am, and where I’d like to be going.

I’m not quite ready for my traditional posts about what I’ve read and written in the past year: for one thing, I often read at least one really great book between Christmas and New Year’s, when the holiday bustle has ended and the book-shaped packages under the tree have revealed their secrets! (In fact, I’m currently reading Emily Wilson’s translation of the Odyssey, which seems a likely contender for any “best of 2018” list.) That doesn’t mean, though, that I’m not looking back over 2018 and ahead to 2019, trying to figure out where I’ve been, where I am, and where I’d like to be going. I do have a sabbatical plan–you have to submit one as part of your application–and also some existing deadlines I need to meet, so I’m not heading into the new year entirely aimless. Still, the precise form my work on that plan will take is really up to me, and figuring that out will be my first and possibly hardest task. A crucial context for me is what I did on and then after my previous sabbatical, in Winter 2015. Over that winter I threw myself into writing what I hoped (and perhaps still do hope) would become a book of “crossover” essays about George Eliot. I wrote a lot of material, and then towards the end of the term I peeled off two parts that I eventually published as self-contained essays. (I did not really appreciate at that point how bad it might be for the book I was imagining to publish a lot of its intended content first.) By and large I enjoyed doing that writing: I felt very motivated and productive, and across my sabbatical my confidence in my overall portfolio grew–which is why I decided, at its end, that I was ready to apply for promotion. This administrative project, too, was initially exhilarating: I had done so much (I thought), in so many different forms, since my first promotion, and the result was (I thought) a body of work I was rightly proud of, some of it well within the usual academic boundaries, but a lot of the more recent work reaching across them or representing my principled resistance to them.

I do have a sabbatical plan–you have to submit one as part of your application–and also some existing deadlines I need to meet, so I’m not heading into the new year entirely aimless. Still, the precise form my work on that plan will take is really up to me, and figuring that out will be my first and possibly hardest task. A crucial context for me is what I did on and then after my previous sabbatical, in Winter 2015. Over that winter I threw myself into writing what I hoped (and perhaps still do hope) would become a book of “crossover” essays about George Eliot. I wrote a lot of material, and then towards the end of the term I peeled off two parts that I eventually published as self-contained essays. (I did not really appreciate at that point how bad it might be for the book I was imagining to publish a lot of its intended content first.) By and large I enjoyed doing that writing: I felt very motivated and productive, and across my sabbatical my confidence in my overall portfolio grew–which is why I decided, at its end, that I was ready to apply for promotion. This administrative project, too, was initially exhilarating: I had done so much (I thought), in so many different forms, since my first promotion, and the result was (I thought) a body of work I was rightly proud of, some of it well within the usual academic boundaries, but a lot of the more recent work reaching across them or representing my principled resistance to them. In the last couple of years the kind of writing I’ve been doing has, more and more, been

In the last couple of years the kind of writing I’ve been doing has, more and more, been  The other question is whether I want–or in some sense need–to stop working (only) in small increments and re-commit myself to a book project, and if so, of what kind? If an essay collection of the kind I have long been playing around with is a non-starter unless I self-publish it (which I might yet do), is there another kind of book I would feel was worth the long-term single-minded effort to produce? I have long objected to the academic fixation on “a book” as a necessary form. I suspect, now, that there is a similar bias in non-academic publishing, or at any rate that one way to get off the kind of plateau I am on is to publish a book of my own which might (at any rate, it seems to have, for others) give me increased visibility and credibility as a critic. I resist that implicit pressure too: I think it’s a good thing to have practising critics who are one step removed from the immediate business of publishing. How long, I wonder, or in what venues, do you have to write reviews before you are perceived as having any stature as a critic, though? How is that kind of professional credit or reputation earned? Do I care? I guess so, or I wouldn’t be wondering! But should I? Is it possible, even if it might in theory be desirable, not to eventually start thinking about going further, doing more, being more?

The other question is whether I want–or in some sense need–to stop working (only) in small increments and re-commit myself to a book project, and if so, of what kind? If an essay collection of the kind I have long been playing around with is a non-starter unless I self-publish it (which I might yet do), is there another kind of book I would feel was worth the long-term single-minded effort to produce? I have long objected to the academic fixation on “a book” as a necessary form. I suspect, now, that there is a similar bias in non-academic publishing, or at any rate that one way to get off the kind of plateau I am on is to publish a book of my own which might (at any rate, it seems to have, for others) give me increased visibility and credibility as a critic. I resist that implicit pressure too: I think it’s a good thing to have practising critics who are one step removed from the immediate business of publishing. How long, I wonder, or in what venues, do you have to write reviews before you are perceived as having any stature as a critic, though? How is that kind of professional credit or reputation earned? Do I care? I guess so, or I wouldn’t be wondering! But should I? Is it possible, even if it might in theory be desirable, not to eventually start thinking about going further, doing more, being more? Here in Halifax we have been socked in with fog and cloud a lot lately, and the last two days in particular have been relentlessly overcast and muggy. The humidity alone is demoralizing, and the absence of sunlight just compounds the gloom. Happily we’re supposed to see at least some sun later today–but most of the rest of the week is forecast to be pretty grey. This kind of disappointing weather is typical of May and June here, but by July we’re usually enjoying a bit more brightness! As our long-awaited and always too-brief summer slips away, it’s hard not to feel a bit depressed, especially as constant construction noise in our usually tranquil neighborhood has made even the few really nice sunny days harder to enjoy. I have hardly spent any time reading on the deck, which is the one summer activity I really look forward to!

Here in Halifax we have been socked in with fog and cloud a lot lately, and the last two days in particular have been relentlessly overcast and muggy. The humidity alone is demoralizing, and the absence of sunlight just compounds the gloom. Happily we’re supposed to see at least some sun later today–but most of the rest of the week is forecast to be pretty grey. This kind of disappointing weather is typical of May and June here, but by July we’re usually enjoying a bit more brightness! As our long-awaited and always too-brief summer slips away, it’s hard not to feel a bit depressed, especially as constant construction noise in our usually tranquil neighborhood has made even the few really nice sunny days harder to enjoy. I have hardly spent any time reading on the deck, which is the one summer activity I really look forward to! My mopey mood has not been helped by the constant barrage of bad news, or by the ceaseless cascade of angry responses to one thing after another on social media. My twitter feed yesterday was heavily dominated, for example, by people being angry about a terrible “take” on libraries and an ill-conceived hit job on Wuthering Heights. I didn’t disagree with (most of) the complaints: I love libraries as much as the next person in my feed, and though Wuthering Heights is

My mopey mood has not been helped by the constant barrage of bad news, or by the ceaseless cascade of angry responses to one thing after another on social media. My twitter feed yesterday was heavily dominated, for example, by people being angry about a terrible “take” on libraries and an ill-conceived hit job on Wuthering Heights. I didn’t disagree with (most of) the complaints: I love libraries as much as the next person in my feed, and though Wuthering Heights is  On the bright side, I just finished reading a pretty good book, Sarah Moss’s Names for the Sea, which I will write a bit more about here soon. I also really liked Kathy Page’s Dear Evelyn, which I just finished writing up for Quill & Quire, and now I’m focusing on a short essay on Carol Shields’ Unless, a novel that has come to be one of my very favorites. I also feel good about my piece on

On the bright side, I just finished reading a pretty good book, Sarah Moss’s Names for the Sea, which I will write a bit more about here soon. I also really liked Kathy Page’s Dear Evelyn, which I just finished writing up for Quill & Quire, and now I’m focusing on a short essay on Carol Shields’ Unless, a novel that has come to be one of my very favorites. I also feel good about my piece on