![]() Before this term picks up much steam (today was the first day of classes, so we are still in the warming-up phase, with its illusions of ease), I thought I’d catch up a bit on last term. I had good intentions to post at least more regularly, if not weekly, as I once did. Maybe it’s boldly declaring such intentions that fatally undermines them! Just in case, I won’t make that mistake here.

Before this term picks up much steam (today was the first day of classes, so we are still in the warming-up phase, with its illusions of ease), I thought I’d catch up a bit on last term. I had good intentions to post at least more regularly, if not weekly, as I once did. Maybe it’s boldly declaring such intentions that fatally undermines them! Just in case, I won’t make that mistake here.

Overall, I think last term was a pretty good one. I had my standard assignment of two courses a term, something we “achieved” (if that’s the right word) years ago by increasing class sizes. (Class sizes have gone up pretty steadily since then, and since numbers are the only case we can apparently make any more for our value, that’s a trend that seems likely to continue.) One of them was yet another iteration of “Literature: How It Works,” one of our core first-year writing requirement classes. I initially designed my current version of this course for online teaching in 2020, during the first COVID lockdown term. I put an enormous amount of effort into it, and especially into its specifications grading system. I taught it online three times and then moved to teaching it in person last fall, after a disastrous term in which 1 in 5 of the students in the class ended up in an academic integrity hearing. This was pre-Chat GPT, so it was all the old-fashioned (!!) “cut and pasted from the internet” variety of plagiarism. I admit I’m a bit nostalgic for those days, and even more for the era of “copied something from a book in the library,” when the student was suddenly using terms like “hermeneutics” or “ekphrasis” and then, when challenged, was unable to explain what they meant. At least they had to go to the library to do that! I remember distinctly showing a suspicious essay on Elizabeth Barrett Browning to my former colleague Marjorie Stone, who took one look at it and said “Oh, that’s from so-and-so’s book,” and of course it was.

How much of a shadow did AI cast over my term? It’s actually a bit hard to say. I tried not to be preoccupied with it. I had just two cases of clear use, both evident from their hallucinations. There were many other submissions that made me wonder. I hated that. I don’t want to be suspicious about my students; I certainly don’t want fluency to become grounds for accusations. I’ve seen a lot of professors confidently declaring that they can spot AI usage. Maybe I’m naïve, or maybe I don’t assign tricky enough questions, or maybe my general expectations are too low, but I’m not nearly so confident. I know what they mean when they talk about the vacuity of AI responses and the other (likely) “tells”—previously rare (for students) words like “delve,” everything coming in threes, too-rapid turns to universalizing proclamations. I caught what I considered a whiff of AI from a lot of students’ assignments. But many of these things used to show up before there was Chat GPT, sometimes because of high school teachers who taught them that’s what good writing or literary analysis should look like, or because some students are authentically fluent, even glib, and nobody has pulled them up short before and demanded they say things that have substance, not just style. I honestly don’t really know how to proceed, pedagogically, beyond continuing to make the best case I can for the reasons to do your own reading, writing and thinking. I do know that I wish we could slow the infiltration of AI into all of the tools we and our students routinely use. I also believe that there are many students still conscientiously doing their own work, and they deserve to have teachers who trust them. I try hard to be that teacher unless evidence to the contrary really stares me in the face.

How much of a shadow did AI cast over my term? It’s actually a bit hard to say. I tried not to be preoccupied with it. I had just two cases of clear use, both evident from their hallucinations. There were many other submissions that made me wonder. I hated that. I don’t want to be suspicious about my students; I certainly don’t want fluency to become grounds for accusations. I’ve seen a lot of professors confidently declaring that they can spot AI usage. Maybe I’m naïve, or maybe I don’t assign tricky enough questions, or maybe my general expectations are too low, but I’m not nearly so confident. I know what they mean when they talk about the vacuity of AI responses and the other (likely) “tells”—previously rare (for students) words like “delve,” everything coming in threes, too-rapid turns to universalizing proclamations. I caught what I considered a whiff of AI from a lot of students’ assignments. But many of these things used to show up before there was Chat GPT, sometimes because of high school teachers who taught them that’s what good writing or literary analysis should look like, or because some students are authentically fluent, even glib, and nobody has pulled them up short before and demanded they say things that have substance, not just style. I honestly don’t really know how to proceed, pedagogically, beyond continuing to make the best case I can for the reasons to do your own reading, writing and thinking. I do know that I wish we could slow the infiltration of AI into all of the tools we and our students routinely use. I also believe that there are many students still conscientiously doing their own work, and they deserve to have teachers who trust them. I try hard to be that teacher unless evidence to the contrary really stares me in the face.

Anyway. The first-year course went fine, I thought. I wish it didn’t have to be a lecture class, but with 90 students (next year we will all have 120), there’s really no other option. I always try to get some class discussion going, and we meet in tutorial groups of “only” 30 once a week as well, but the real answer to “what to do about AI” is the same as the answer to most pedagogical problems we have: smaller classes, closer relationships, more individual attention, especially to their writing. I probably won’t be teaching a first-year class next year, for the first time in a long time, because I will have a course release for serving as our undergraduate program coordinator. In part but not just because of AI, I am glad for the chance to give the course a refresh, maybe even a complete redesign. I want to keep using specifications grading but I’d like to reconsider the components and bundles I devised. I want to think about the readings again, too, maybe moving towards more deliberate thematic groupings, or including some full-length novels again. When you teach a course for several years in a row the easiest thing to do is repeat what you just did, because the deadlines for course proposals and timetabling and book orders come earlier and earlier. I’ve done a lot of different first-year classes since I started at Dalhousie in 1995. Who knows: the next version I develop might be my last! And maybe by the time I am offering it, probably in Fall 2026, the AI bubble will have burst. I mean, surely at some point the fact that it is no good—that it spews bullshit and destroys the environment and relies on theft—will matter, right? RIGHT?

Anyway. The first-year course went fine, I thought. I wish it didn’t have to be a lecture class, but with 90 students (next year we will all have 120), there’s really no other option. I always try to get some class discussion going, and we meet in tutorial groups of “only” 30 once a week as well, but the real answer to “what to do about AI” is the same as the answer to most pedagogical problems we have: smaller classes, closer relationships, more individual attention, especially to their writing. I probably won’t be teaching a first-year class next year, for the first time in a long time, because I will have a course release for serving as our undergraduate program coordinator. In part but not just because of AI, I am glad for the chance to give the course a refresh, maybe even a complete redesign. I want to keep using specifications grading but I’d like to reconsider the components and bundles I devised. I want to think about the readings again, too, maybe moving towards more deliberate thematic groupings, or including some full-length novels again. When you teach a course for several years in a row the easiest thing to do is repeat what you just did, because the deadlines for course proposals and timetabling and book orders come earlier and earlier. I’ve done a lot of different first-year classes since I started at Dalhousie in 1995. Who knows: the next version I develop might be my last! And maybe by the time I am offering it, probably in Fall 2026, the AI bubble will have burst. I mean, surely at some point the fact that it is no good—that it spews bullshit and destroys the environment and relies on theft—will matter, right? RIGHT?

My other class was The 19th-Century British Novel from Dickens to Hardy. I enjoyed it so much! The reading list was one I haven’t done since 2017: Bleak House, Adam Bede, Lady Audley’s Secret, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. It was particularly lovely to hear so many students say they had no fears about Bleak House because they had enjoyed David Copperfield so much last year in the Austen to Dickens course. I think I have mentioned before in these posts that in recent years I have been making a conscious effort to wean myself from my teaching notes. I still prepare and bring quite a lot of notes, but I try to let that preparation sit in the background and set up topics and examples for discussion that then proceeds in a looser way. The notes are always there if I think we are losing focus or running out of steam, but I don’t worry about whether I’m following the plan I came with. It was interesting, then, to dip into my notes from that 2017 version, because I realized how much my approach has in fact changed since then. I was very glad to have them to draw on and adapt, but although if you’d asked me in 2017 whether I did much “formal” lecturing I would have said I did not, in fact they show that I did run much more scripted classes than I do now. The things I want to talk about have not changed that much, although of course I do browse recent criticism and introduce new angles or approaches that interest me. Basically, though, I guess my attitude to this class (and the Austen to Dickens one) is “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”: I believe them to be rigorous, stimulating, and fun, and students seem to agree. Unlike the first-year course, then, these ones are likely to stay more or less the same until I retire. More or less, not exactly! They have evolved a lot already, in more ways than my own teaching style, and I will not let them go stale. I wouldn’t want that for my own sake, never mind for my students’.

My other class was The 19th-Century British Novel from Dickens to Hardy. I enjoyed it so much! The reading list was one I haven’t done since 2017: Bleak House, Adam Bede, Lady Audley’s Secret, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. It was particularly lovely to hear so many students say they had no fears about Bleak House because they had enjoyed David Copperfield so much last year in the Austen to Dickens course. I think I have mentioned before in these posts that in recent years I have been making a conscious effort to wean myself from my teaching notes. I still prepare and bring quite a lot of notes, but I try to let that preparation sit in the background and set up topics and examples for discussion that then proceeds in a looser way. The notes are always there if I think we are losing focus or running out of steam, but I don’t worry about whether I’m following the plan I came with. It was interesting, then, to dip into my notes from that 2017 version, because I realized how much my approach has in fact changed since then. I was very glad to have them to draw on and adapt, but although if you’d asked me in 2017 whether I did much “formal” lecturing I would have said I did not, in fact they show that I did run much more scripted classes than I do now. The things I want to talk about have not changed that much, although of course I do browse recent criticism and introduce new angles or approaches that interest me. Basically, though, I guess my attitude to this class (and the Austen to Dickens one) is “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”: I believe them to be rigorous, stimulating, and fun, and students seem to agree. Unlike the first-year course, then, these ones are likely to stay more or less the same until I retire. More or less, not exactly! They have evolved a lot already, in more ways than my own teaching style, and I will not let them go stale. I wouldn’t want that for my own sake, never mind for my students’.

This is all very general, without the kind of “here’s what we talked about today” specificity that I used to incorporate when I really did post nearly every week about my classes. (There are 318 posts in that ‘category,’ can you believe it?!) The best reason I have for wanting to get back to that kind of routine posting is that I miss it: I think, too, that it helped my teaching evolve, that the writing both prompted and supported me as I tried to become a better—more reflective, more responsive, more effective—teacher. So without making a bold pronouncement, a promise I maybe won’t be able to keep, I will say that I would like to post more regularly about teaching in 2025. I said a little while ago that, after the past few very difficult and disruptive years, I wanted to be genuinely and meaningfully present for the last stage of my professional life. Odd as it may seem, blogging about it seems to me one way to live up to that aspiration.

This is all very general, without the kind of “here’s what we talked about today” specificity that I used to incorporate when I really did post nearly every week about my classes. (There are 318 posts in that ‘category,’ can you believe it?!) The best reason I have for wanting to get back to that kind of routine posting is that I miss it: I think, too, that it helped my teaching evolve, that the writing both prompted and supported me as I tried to become a better—more reflective, more responsive, more effective—teacher. So without making a bold pronouncement, a promise I maybe won’t be able to keep, I will say that I would like to post more regularly about teaching in 2025. I said a little while ago that, after the past few very difficult and disruptive years, I wanted to be genuinely and meaningfully present for the last stage of my professional life. Odd as it may seem, blogging about it seems to me one way to live up to that aspiration.

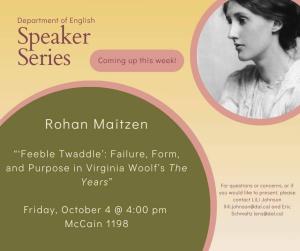

OK, onward! This term I’m teaching a seminar on Victorian women writers and the mystery fiction class. I’m genuinely enthusiastic about both of them. Wednesday is “orientation day,” with overview lectures in both classes. Then on Friday it’s a selection of Victorian writing on women writers in the seminar, including George Eliot’s scathing and hilarious and, perhaps, inspirational “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists” and George Henry Lewes’s “The Lady Novelists” (don’t you wish you could overhear their dinner table conversations about this?); and in the mystery class it’s Poe’s delightfully gruesome “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” . . . and that’s what’s up this week in my classes!

What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be  I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s

I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s

In my

In my  So I started 2024 by clearing out a lot of books. The other change since the separation has been to my reading time. I don’t quite understand why, but there seem to be a lot more hours in the day now that I live alone! I have wasted an awful lot of them watching TV, and many of them idly scrolling online, and plenty also just moping or mourning. I think (though this may be just making excuses) that I should not be too hard on myself about these bad habits, as the past few years have been pretty tough and we are all entitled to our coping strategies. I make intermittent resolutions to do better, to use my time better; I have made some of these for 2025. (Yes, blogging regularly again is one of them. We’ll see.) However! I have had more time for reading, and I have sometimes taken advantage of it. I have especially enjoyed taking time to read in the mornings. For many years—around two decades, really—mornings were my least favorite time of the day, what with all the kid stuff (breakfasts, lunches, getting dressed, remembering backpacks and permission slips and other forms, trying to get out the door on time) on top of bracing for my own work days, with the non-trivial (for me) anxiety of driving in winter weather adding a nice additional layer of stress from November through April. Things were simpler once the kids were older then out of the house, but I never felt like it was a good time for relaxing: I still had to get off to work, for one thing. Now, between habitually waking up early and living easy walking distance to work, even on weekdays I can afford to get in some peaceful reading while I have my tea and toast. We used to end most days in front of the TV; I still do that, especially on days when I’ve read a lot for work, but other days I can settle into my reading chair, put on some quiet music, and there’s nothing and nobody to interrupt me.

So I started 2024 by clearing out a lot of books. The other change since the separation has been to my reading time. I don’t quite understand why, but there seem to be a lot more hours in the day now that I live alone! I have wasted an awful lot of them watching TV, and many of them idly scrolling online, and plenty also just moping or mourning. I think (though this may be just making excuses) that I should not be too hard on myself about these bad habits, as the past few years have been pretty tough and we are all entitled to our coping strategies. I make intermittent resolutions to do better, to use my time better; I have made some of these for 2025. (Yes, blogging regularly again is one of them. We’ll see.) However! I have had more time for reading, and I have sometimes taken advantage of it. I have especially enjoyed taking time to read in the mornings. For many years—around two decades, really—mornings were my least favorite time of the day, what with all the kid stuff (breakfasts, lunches, getting dressed, remembering backpacks and permission slips and other forms, trying to get out the door on time) on top of bracing for my own work days, with the non-trivial (for me) anxiety of driving in winter weather adding a nice additional layer of stress from November through April. Things were simpler once the kids were older then out of the house, but I never felt like it was a good time for relaxing: I still had to get off to work, for one thing. Now, between habitually waking up early and living easy walking distance to work, even on weekdays I can afford to get in some peaceful reading while I have my tea and toast. We used to end most days in front of the TV; I still do that, especially on days when I’ve read a lot for work, but other days I can settle into my reading chair, put on some quiet music, and there’s nothing and nobody to interrupt me.

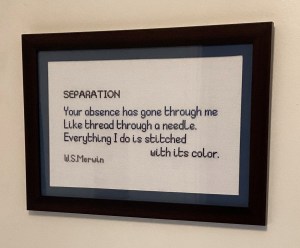

I also remember how angry it made me, in what I now know to call the “acute” phase of grief, to be told “it takes time.” Time for

I also remember how angry it made me, in what I now know to call the “acute” phase of grief, to be told “it takes time.” Time for  Like Riley, whose meditations on grief have been interwoven with my own since almost the beginning, after three years I have nearly stopped writing about it, at least publicly. As I realized long ago, there is a terrible

Like Riley, whose meditations on grief have been interwoven with my own since almost the beginning, after three years I have nearly stopped writing about it, at least publicly. As I realized long ago, there is a terrible

She was surprised to find it more or less possible, most of the time, to follow her meal plan: it seemed that perhaps the battle was over, the endgame complete. She had followed the rules all the way to the end, until it was possible to go no further. She had met the experts’ standards until her heart and liver and kidneys failed in quantifiable and quantified ways, until other experts told her that it was time to stop and now, surely, there must be a period of grade, a little mercy.

She was surprised to find it more or less possible, most of the time, to follow her meal plan: it seemed that perhaps the battle was over, the endgame complete. She had followed the rules all the way to the end, until it was possible to go no further. She had met the experts’ standards until her heart and liver and kidneys failed in quantifiable and quantified ways, until other experts told her that it was time to stop and now, surely, there must be a period of grade, a little mercy. That instant, the memory of a long-lost word rises up in her, cut in half, and she tries to grab hold of it. She had learned that, in times past, there had been a word, a Hanja word . . . by which people had referred to the half-light just after the sun sets and just before it rises. A word that means having to call out in a loud voice, as the person approaching from a distance is too far away to be recognized, to ask who they are . . . This eternally incomplete, eternally unwhole word stirs deep within her, never reaching her throat.

That instant, the memory of a long-lost word rises up in her, cut in half, and she tries to grab hold of it. She had learned that, in times past, there had been a word, a Hanja word . . . by which people had referred to the half-light just after the sun sets and just before it rises. A word that means having to call out in a loud voice, as the person approaching from a distance is too far away to be recognized, to ask who they are . . . This eternally incomplete, eternally unwhole word stirs deep within her, never reaching her throat. And yet overall I was captivated by Greek Lessons, not so much by its particulars as by the melancholy space it created. Ordinarily I prefer some forward momentum in a novel (both cause and effect of my specializing in the 19th-century novel for so long!). What Greek Lessons offers instead, or this is how it felt to me, is a kind of time out, from that fictional drive and also from the busy world that these days overwhelms us with “content” and noise. In the intimacy of the portrayal of these two people, both of whom are retreating from the world partly by choice but mostly from the cruelty of their circumstances, there is some recognition of how hard it is to be ourselves, to be authentic, to see each other. The quiet sparseness of Han Kang’s writing could be seen as an antidote to the pressure to perform who we are and to insist on making space for ourselves out there. (Pressured by her therapist to break her silence, the woman thinks, “she still did not wish to take up more space.”)

And yet overall I was captivated by Greek Lessons, not so much by its particulars as by the melancholy space it created. Ordinarily I prefer some forward momentum in a novel (both cause and effect of my specializing in the 19th-century novel for so long!). What Greek Lessons offers instead, or this is how it felt to me, is a kind of time out, from that fictional drive and also from the busy world that these days overwhelms us with “content” and noise. In the intimacy of the portrayal of these two people, both of whom are retreating from the world partly by choice but mostly from the cruelty of their circumstances, there is some recognition of how hard it is to be ourselves, to be authentic, to see each other. The quiet sparseness of Han Kang’s writing could be seen as an antidote to the pressure to perform who we are and to insist on making space for ourselves out there. (Pressured by her therapist to break her silence, the woman thinks, “she still did not wish to take up more space.”) November wasn’t a bad reading month, considering how busy things were at work—and considering that “work” also means reading a fair amount, this time around including most of both Lady Audley’s Secret and Tess of the d’Urbervilles for 19thC Fiction and an array of short fiction and poetry for my intro class. (I have not managed to get back into a routine of posting about my teaching, but I would like to, so we’ll see what happens next term.)

November wasn’t a bad reading month, considering how busy things were at work—and considering that “work” also means reading a fair amount, this time around including most of both Lady Audley’s Secret and Tess of the d’Urbervilles for 19thC Fiction and an array of short fiction and poetry for my intro class. (I have not managed to get back into a routine of posting about my teaching, but I would like to, so we’ll see what happens next term.)

I felt the need for something cheering in the wake of The Election and landed on Connie Willis’s To Say Nothing of the Dog: it was a great choice, genuinely comic and warm-hearted but also endlessly clever. I had a lot of LOL moments over its characterizations of the Victorian period, and it is chock full of literary allusions, many of which I’m sure I didn’t catch. A lot of them are to Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers: who know that Gaudy Night would be one of its main running references. I liked it enough that I’ve put The Doomsday Book on my Christmas wish list, even though I don’t ordinarily gravitate towards this genre.

I felt the need for something cheering in the wake of The Election and landed on Connie Willis’s To Say Nothing of the Dog: it was a great choice, genuinely comic and warm-hearted but also endlessly clever. I had a lot of LOL moments over its characterizations of the Victorian period, and it is chock full of literary allusions, many of which I’m sure I didn’t catch. A lot of them are to Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers: who know that Gaudy Night would be one of its main running references. I liked it enough that I’ve put The Doomsday Book on my Christmas wish list, even though I don’t ordinarily gravitate towards this genre. I knew I would read Noémi Kiss-Deáki’s Mary and the Rabbit Dream the first time I heard about it. It sounded like exactly my kind of thing: a fresh style of historical fiction, with a strange and subversive story to tell. It was published in the UK by Galley Beggar Press—and maybe that should have been a red flag for me, as they are the publishers and champions of Lucy Ellmann, whose Ducks, Newburyport I have begun three times, never making it more than 30 pages, but more significantly (because I still believe Ducks, Newburyport may be worth yet another try) whose Things Are Against Us I absolutely hated. On the other hand, I didn’t hate After Sappho, which they also published, and I do try, on principle, to push my own reading boundaries. So when Coach House Press here in Canada put out their edition of Mary and the Rabbit Dream, I promptly picked it up and happily began it.

I knew I would read Noémi Kiss-Deáki’s Mary and the Rabbit Dream the first time I heard about it. It sounded like exactly my kind of thing: a fresh style of historical fiction, with a strange and subversive story to tell. It was published in the UK by Galley Beggar Press—and maybe that should have been a red flag for me, as they are the publishers and champions of Lucy Ellmann, whose Ducks, Newburyport I have begun three times, never making it more than 30 pages, but more significantly (because I still believe Ducks, Newburyport may be worth yet another try) whose Things Are Against Us I absolutely hated. On the other hand, I didn’t hate After Sappho, which they also published, and I do try, on principle, to push my own reading boundaries. So when Coach House Press here in Canada put out their edition of Mary and the Rabbit Dream, I promptly picked it up and happily began it. There is a lot that is good and interesting about this novel, especially the way that, while it centers sympathetically on Mary and her experience, it also uses her story as a device to expose the cruelty of misogyny and the punishing self-satisfaction of a certain species of scientific certitude. There is a particularly harrowing scene in which a powerful man, determined to break her and expose her as the fraud he is sure she is, threatens Mary with live vivisection, explaining to her with truly menacing “objectivity” that

There is a lot that is good and interesting about this novel, especially the way that, while it centers sympathetically on Mary and her experience, it also uses her story as a device to expose the cruelty of misogyny and the punishing self-satisfaction of a certain species of scientific certitude. There is a particularly harrowing scene in which a powerful man, determined to break her and expose her as the fraud he is sure she is, threatens Mary with live vivisection, explaining to her with truly menacing “objectivity” that I might have tolerated the long stretches of this kind of stuff better if they hadn’t so often devolved into heavy-handed comments on what is perfectly obvious from the story itself, about how vile and prejudiced and uncaring the men are; or about how unfair the whole system is, especially to Mary (as happens in the example above); or about the symbolic meaning of what is going on. The worst such moment was this one, right after Mary, in excruciating pain and exhausted from relentless examinations, breaks down and begins screaming (“she slips down on the floor, she starts screaming, she screams and screams and screams”):

I might have tolerated the long stretches of this kind of stuff better if they hadn’t so often devolved into heavy-handed comments on what is perfectly obvious from the story itself, about how vile and prejudiced and uncaring the men are; or about how unfair the whole system is, especially to Mary (as happens in the example above); or about the symbolic meaning of what is going on. The worst such moment was this one, right after Mary, in excruciating pain and exhausted from relentless examinations, breaks down and begins screaming (“she slips down on the floor, she starts screaming, she screams and screams and screams”): Claudia Piñeiro’s Time of the Flies is, like the other novels of hers that I’ve read, a crime novel. Sort of. It is about a convicted murderer, Inés: she killed her husband’s lover, but at the time of the novel is out of prison and making her living running an environmentally friendly pest control business. Then she is approached by one of her clients to provide a deadly pesticide—so that she too can kill “a woman who wants to take my husband the same way yours was taken from you,” or so she tells Inés. Inés, who is not in general a murderous person and who also would very much like not to go back to prison, is tempted only because her friend Manca urgently needs treatment for breast cancer but can’t afford to pay to get it right away. The situation gets more complicated when a connection emerges between the client and the daughter Inés has not seen since her imprisonment.

Claudia Piñeiro’s Time of the Flies is, like the other novels of hers that I’ve read, a crime novel. Sort of. It is about a convicted murderer, Inés: she killed her husband’s lover, but at the time of the novel is out of prison and making her living running an environmentally friendly pest control business. Then she is approached by one of her clients to provide a deadly pesticide—so that she too can kill “a woman who wants to take my husband the same way yours was taken from you,” or so she tells Inés. Inés, who is not in general a murderous person and who also would very much like not to go back to prison, is tempted only because her friend Manca urgently needs treatment for breast cancer but can’t afford to pay to get it right away. The situation gets more complicated when a connection emerges between the client and the daughter Inés has not seen since her imprisonment.

That might be a good explanation for the hybrid nature of Time of the Flies, but it doesn’t necessarily make the book a success. I’d probably have to read it again (and again) to make up my mind about that, which I might do, given that I offer a course called “Women and Detective Fiction.” Last time around I almost assigned Elena Knows for it. Another title I’ve considered for the book list is Jo Baker’s The Body Lies, which is quite unlike Time of the Flies except that it too is a crime novel that turns out to be about crime novels, and especially about the roles and depiction of women in them, the voyeurism of violence against women, the prurient fixation on their wounded or dead bodies, the genre variations that both do and don’t reconfigure women’s relationship to the stories we tell about crime and violence. I thought Baker’s novel was excellent. I certainly didn’t have any trouble finishing it, in contrast to the concerted effort I made to get to the end of Time of the Flies. I really did want to know what happened! But I felt like I had to wade through a lot of other stuff to get there. If I do reread it, maybe that stuff will turn out to be the real substance of the book.

That might be a good explanation for the hybrid nature of Time of the Flies, but it doesn’t necessarily make the book a success. I’d probably have to read it again (and again) to make up my mind about that, which I might do, given that I offer a course called “Women and Detective Fiction.” Last time around I almost assigned Elena Knows for it. Another title I’ve considered for the book list is Jo Baker’s The Body Lies, which is quite unlike Time of the Flies except that it too is a crime novel that turns out to be about crime novels, and especially about the roles and depiction of women in them, the voyeurism of violence against women, the prurient fixation on their wounded or dead bodies, the genre variations that both do and don’t reconfigure women’s relationship to the stories we tell about crime and violence. I thought Baker’s novel was excellent. I certainly didn’t have any trouble finishing it, in contrast to the concerted effort I made to get to the end of Time of the Flies. I really did want to know what happened! But I felt like I had to wade through a lot of other stuff to get there. If I do reread it, maybe that stuff will turn out to be the real substance of the book.

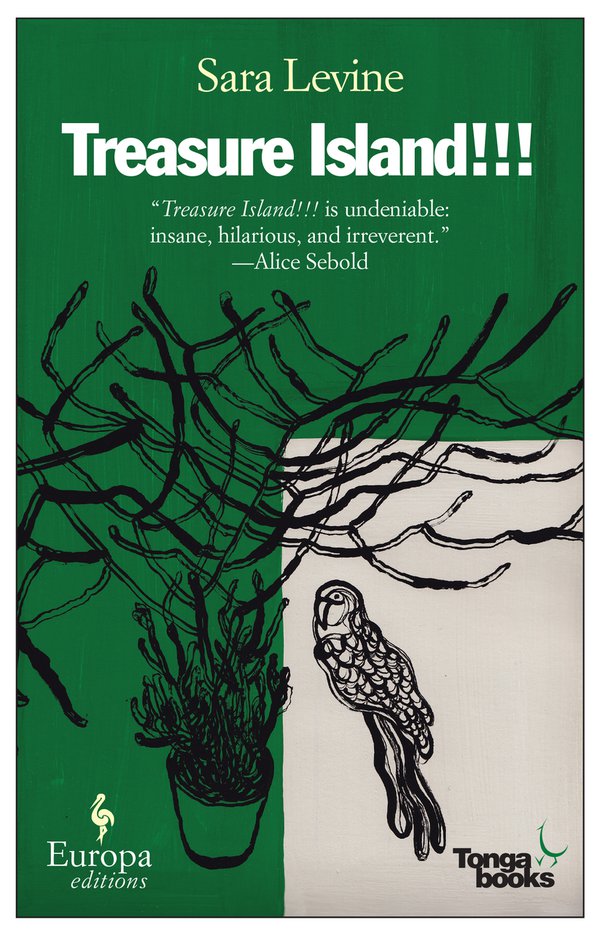

That said, I did quite enjoy Sara Levine’s Treasure Island!!!, which I picked up quite randomly at the library, mostly because it’s a Europa Edition but also because I vaguely recalled hearing good things about it online. It turned out to be a sharp and very funny send-up of the “great literature transformed my life” genre. Its narrator, whose life is in something of a shambles, reads Treasure Island and decides it offers her a template for turning things around. She adopts the novel’s “Core Values”—BOLDNESS, RESOLUTION, INDEPENDENCE, HORN-BLOWING—and applies them to her job (which, improbably and hilariously, is at a “pet hotel,” where clients sign out cats, dogs, rabbits, even goldfish), her boyfriend, and her family, with hilarious if also sometimes weirdly poignant results. I have such a love-hate relationship with books that purport to turn literature into self-help manuals that I relished the premise, but Levine uses it as a launching point for something much zanier than I could possibly have expected or can possibly summarize.

That said, I did quite enjoy Sara Levine’s Treasure Island!!!, which I picked up quite randomly at the library, mostly because it’s a Europa Edition but also because I vaguely recalled hearing good things about it online. It turned out to be a sharp and very funny send-up of the “great literature transformed my life” genre. Its narrator, whose life is in something of a shambles, reads Treasure Island and decides it offers her a template for turning things around. She adopts the novel’s “Core Values”—BOLDNESS, RESOLUTION, INDEPENDENCE, HORN-BLOWING—and applies them to her job (which, improbably and hilariously, is at a “pet hotel,” where clients sign out cats, dogs, rabbits, even goldfish), her boyfriend, and her family, with hilarious if also sometimes weirdly poignant results. I have such a love-hate relationship with books that purport to turn literature into self-help manuals that I relished the premise, but Levine uses it as a launching point for something much zanier than I could possibly have expected or can possibly summarize.