I’m just over half way through the ‘Drawing for Beginners’ class I signed up for, and as some of you may have noticed on Twitter, I have been feeling quite frustrated about the way it is going so far. I am trying to learn lessons from my frustration, but despite how ready a few people have been to suggest this, I honestly don’t think a fair conclusion is that I am receiving some valuable schooling about my own teaching. Rather, my frustrations mostly reinforce my own pedagogical strategies and priorities. They may not be perfect, and I may not implement them perfectly, but as far as they–and I–go, I think I have the right idea. *

I’m just over half way through the ‘Drawing for Beginners’ class I signed up for, and as some of you may have noticed on Twitter, I have been feeling quite frustrated about the way it is going so far. I am trying to learn lessons from my frustration, but despite how ready a few people have been to suggest this, I honestly don’t think a fair conclusion is that I am receiving some valuable schooling about my own teaching. Rather, my frustrations mostly reinforce my own pedagogical strategies and priorities. They may not be perfect, and I may not implement them perfectly, but as far as they–and I–go, I think I have the right idea. *

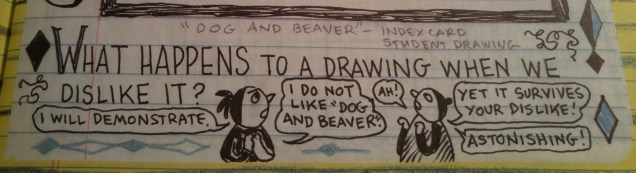

I’m not frustrated that, after just three weeks, I still can’t draw well. I was prepared for it to take a while, and plenty of practice, for me to get any better! I’m frustrated because so far, I don’t much sense of how to improve, except to keep drawing badly until eventually, somehow, I’m drawing better. Although we have done a bit of work on explicit techniques, such as shading, we’ve mostly just been told to draw things, either from life or by copying or finishing other drawings or pictures, and reassured (if that’s the right word) that we’ll get better with practice. To me, that seems more or less the pedagogical equivalent of my putting a poem in front of someone and saying “here, write about this,” without explaining at all what “this” is, or being more specific about what I mean by “write about,” or breaking the task down into its component steps.

Maybe there isn’t an equivalent way to break down the process for learning to draw. Or maybe the direction to “look closely and draw what you see” (including if it’s upside-down) is closer than it feels to my frequent instruction to “read carefully and comment on what you notice.” I recognize that there isn’t really a way to built up a collective sense of how to do the work, the way we do in my classes through discussion of our readings. Our instructor doesn’t demonstrate our tasks for us: I don’t know if it would help if she did. In any case, I do realize that just as ultimately there’s no substitute for actually putting some words in order and seeing what they say, there’s no alternative to making marks with your pencil and seeing what they look like. In a way, what counts as success in drawing is clearer: your picture either looks like its subject or it doesn’t! That sense that there is a “right” result is one of the things I’ve been finding stressful–ironically, perhaps, I know my own students sometimes feel annoyed that there isn’t one right interpretation, or one perfect way to write their essays.

Maybe there isn’t an equivalent way to break down the process for learning to draw. Or maybe the direction to “look closely and draw what you see” (including if it’s upside-down) is closer than it feels to my frequent instruction to “read carefully and comment on what you notice.” I recognize that there isn’t really a way to built up a collective sense of how to do the work, the way we do in my classes through discussion of our readings. Our instructor doesn’t demonstrate our tasks for us: I don’t know if it would help if she did. In any case, I do realize that just as ultimately there’s no substitute for actually putting some words in order and seeing what they say, there’s no alternative to making marks with your pencil and seeing what they look like. In a way, what counts as success in drawing is clearer: your picture either looks like its subject or it doesn’t! That sense that there is a “right” result is one of the things I’ve been finding stressful–ironically, perhaps, I know my own students sometimes feel annoyed that there isn’t one right interpretation, or one perfect way to write their essays.

I’m also frustrated because I haven’t really been enjoying myself. I thought (foolishly, perhaps) that there would be something freeing about this experience. In part, I blame Lynda Barry! You’d never know from Syllabus that drawing can be really hard work: she makes art seem so joyous and self-criticism seem counter-productive. The goal of getting the drawings exactly right has been one of the things stifling my joy. I know that we aren’t in fact expected to get them right yet, of course: we’re just learning. Still, when there’s the shoe right in front of me, and then there’s my deformed rendition of it in my sketchbook, it’s hard to hang on to Barry’s injunction that it’s fine to be bad at things. There was a bit of a mismatch, too, between what I thought I was signing up for and what we discovered on the first day was going to be the emphasis of the class: the flyer did not specify life drawing or portraiture, but that turns out to be what our instructor is focusing on. Faces are really hard! Asking a rank beginner to draw eyes just seems like a recipe for discouragement–especially if the originals belong to Julianna Margulies.

I’m also frustrated because I haven’t really been enjoying myself. I thought (foolishly, perhaps) that there would be something freeing about this experience. In part, I blame Lynda Barry! You’d never know from Syllabus that drawing can be really hard work: she makes art seem so joyous and self-criticism seem counter-productive. The goal of getting the drawings exactly right has been one of the things stifling my joy. I know that we aren’t in fact expected to get them right yet, of course: we’re just learning. Still, when there’s the shoe right in front of me, and then there’s my deformed rendition of it in my sketchbook, it’s hard to hang on to Barry’s injunction that it’s fine to be bad at things. There was a bit of a mismatch, too, between what I thought I was signing up for and what we discovered on the first day was going to be the emphasis of the class: the flyer did not specify life drawing or portraiture, but that turns out to be what our instructor is focusing on. Faces are really hard! Asking a rank beginner to draw eyes just seems like a recipe for discouragement–especially if the originals belong to Julianna Margulies.

Last night, though, I actually had fun for very nearly the first time, because we worked for a while on landscapes. They seem much more forgiving subjects than people, at least if you aren’t trying to incorporate architectural structures or to get every feature precisely accurate. Though my trees look pretty spindly and my mountains are, shall we say, impressionistic, still, it is recognizably a picture of trees and mountains, and it didn’t feel wrong to improvise a bit when I found the original drawing I was copying hard to reproduce. My fantasy about being able to draw has a lot to do with sketching expeditions to picturesque locations in Victorian novels and very little to do with portraiture; working on this picture, for once I could imagine being happily ensconced somewhere picturesque myself, sketchbook and pencils at the ready.

It isn’t that I don’t want to be more skillful, but as a beginner, and an anxious perfectionist beginner at that, I found the experience of drawing more loosely very helpful. I do want to master (or at least improve at) the more technical aspects, and obviously I’ll never do good landscape drawings if I don’t. It was just a relief to do something besides trying and failing to draw perfectly realistic eyes, hands, or shoes–something that allowed for a bit more creativity. It restored my enthusiasm for this experiment!

*Update: It’s actually mystifying to me that anyone would think this is some kind of “gotcha” moment for me: I have written a lot here over the years about my strategies for helping students past their difficulties in my own classes, I’ve never imagined they don’t experience frustration, and I’ve reflected explicitly on the value for me, as a teacher, of being a beginner at something myself–including in the context of my decision to take this drawing class. And yet I have had just that response more than once, including moments after I shared the link to this post.

Jane Austen recommended three or four families in the Country Village as the thing to work on when planning a novel. . . . A few families in a Country Village. A few families in a small, densely populated, parochial, insecure country. Mothers, fathers, aunts, stepchildren, cousins. Where does the story begin and where does it end?

Jane Austen recommended three or four families in the Country Village as the thing to work on when planning a novel. . . . A few families in a Country Village. A few families in a small, densely populated, parochial, insecure country. Mothers, fathers, aunts, stepchildren, cousins. Where does the story begin and where does it end? As this passage illustrates, The Radiant Way is about the condition of England in the 1980s, and its treatment of that era matches, rather than counters, what it suggests is the spirit of the age: it is (mostly) satirical, snide, cynical, bitter. I wonder if that is why it seemed to me so much more dated than, say, Mary Barton, with its heartfelt appeals to our common experiences and better natures. There is something naive, of course, about Gaskell’s novel, and many of her attitudes are outdated. Maybe I just prefer her kindness and optimism to Drabble’s somewhat ruthless explication of people’s weaknesses and compromises. The extent to which her analysis is still painfully current, too, shows that if anything she was prescient about the corrosion of the welfare state, the devaluation of art and education, and the instability of love as a foundation for happiness. Maybe I just wish it were dated.

As this passage illustrates, The Radiant Way is about the condition of England in the 1980s, and its treatment of that era matches, rather than counters, what it suggests is the spirit of the age: it is (mostly) satirical, snide, cynical, bitter. I wonder if that is why it seemed to me so much more dated than, say, Mary Barton, with its heartfelt appeals to our common experiences and better natures. There is something naive, of course, about Gaskell’s novel, and many of her attitudes are outdated. Maybe I just prefer her kindness and optimism to Drabble’s somewhat ruthless explication of people’s weaknesses and compromises. The extent to which her analysis is still painfully current, too, shows that if anything she was prescient about the corrosion of the welfare state, the devaluation of art and education, and the instability of love as a foundation for happiness. Maybe I just wish it were dated. I read The Radiant Way for my book club (it’s our follow-up to

I read The Radiant Way for my book club (it’s our follow-up to  I’ve been in a bit of a reading slump lately, which has been reflected in the slow pace of my blogging. I’m not sure exactly what is behind it this time, but I think it happens to all of us occasionally, and it always passes eventually. Still, it’s a disheartening phase when it comes, to be picking up books and putting them down again without much caring!

I’ve been in a bit of a reading slump lately, which has been reflected in the slow pace of my blogging. I’m not sure exactly what is behind it this time, but I think it happens to all of us occasionally, and it always passes eventually. Still, it’s a disheartening phase when it comes, to be picking up books and putting them down again without much caring! I also started Lee Child’s Killing Floor, the first of his hugely popular Jack Reacher thrillers. I admit it had never occurred to me to try this series until Stig Abell, the editor of the TLS, sang its praises. I had no particular assumptions about Lee Child, good or bad, it’s just that the books had never stood out to me until Abell said how much he’d enjoyed reading through them all last year–so I picked up a couple at a book sale. I got about half way through Killing Floor before I lost interest. I don’t think there’s anything really wrong with this book any more than there is anything wrong with The Mirror Thief: in fact, I thought Killing Floor seemed quite good of its kind. But for whatever reason I just wasn’t gripped–I wasn’t even slightly curious about how the knotty plot was going to turn out, and so I eventually stopped picking it up again after I put it down. When I started it, it reminded me of Robert B. Parker’s Spenser mysteries, which I love. It is much wordier, and it may be that I wouldn’t enjoy Parker’s books if it took a lot longer for things to happen in them–or if Parker spent as much more time on the really grim bits as Child does here. I also didn’t bond with Reacher. I was intrigued by Child’s introduction, in which he outlines his own motivations for the style of the series as a whole and for Reacher’s character in particular. Reacher is deliberately both arrogant and hard to like, which are not qualities I’m against in principle, in a main character–but again, I don’t imagine I would like Parker’s books if I didn’t find Spenser’s combination of strength and honor so appealing. Maybe I’ll appreciate Reacher more as a character if/when I get to know him better. For now, though, I’ve put him on hold.

I also started Lee Child’s Killing Floor, the first of his hugely popular Jack Reacher thrillers. I admit it had never occurred to me to try this series until Stig Abell, the editor of the TLS, sang its praises. I had no particular assumptions about Lee Child, good or bad, it’s just that the books had never stood out to me until Abell said how much he’d enjoyed reading through them all last year–so I picked up a couple at a book sale. I got about half way through Killing Floor before I lost interest. I don’t think there’s anything really wrong with this book any more than there is anything wrong with The Mirror Thief: in fact, I thought Killing Floor seemed quite good of its kind. But for whatever reason I just wasn’t gripped–I wasn’t even slightly curious about how the knotty plot was going to turn out, and so I eventually stopped picking it up again after I put it down. When I started it, it reminded me of Robert B. Parker’s Spenser mysteries, which I love. It is much wordier, and it may be that I wouldn’t enjoy Parker’s books if it took a lot longer for things to happen in them–or if Parker spent as much more time on the really grim bits as Child does here. I also didn’t bond with Reacher. I was intrigued by Child’s introduction, in which he outlines his own motivations for the style of the series as a whole and for Reacher’s character in particular. Reacher is deliberately both arrogant and hard to like, which are not qualities I’m against in principle, in a main character–but again, I don’t imagine I would like Parker’s books if I didn’t find Spenser’s combination of strength and honor so appealing. Maybe I’ll appreciate Reacher more as a character if/when I get to know him better. For now, though, I’ve put him on hold. It’s not as if I haven’t read any books all the way through since classes ended. One thing that works is coercion! I’ve read two books for reviews, one an interesting study of Agatha Christie, the other a new novel by Canadian writer Merilyn Simonds. (My review of the former has been filed; my review of the latter is underway.) I’m also making good progress on Margaret Drabble’s The Radiant Way, which I need to finish for next weekend’s meeting of my book club. Deadlines are useful things. In the interstices of my days I’ve also reread all three of

It’s not as if I haven’t read any books all the way through since classes ended. One thing that works is coercion! I’ve read two books for reviews, one an interesting study of Agatha Christie, the other a new novel by Canadian writer Merilyn Simonds. (My review of the former has been filed; my review of the latter is underway.) I’m also making good progress on Margaret Drabble’s The Radiant Way, which I need to finish for next weekend’s meeting of my book club. Deadlines are useful things. In the interstices of my days I’ve also reread all three of  Classes have been over for a while now, but the business of the teaching term isn’t quite over. I mentioned before that one unfortunate feature of marking season is academic integrity hearings: I had more this year than I’ve ever had before, which has taken up a lot of my time and also given me a lot to think about. Individual cases are confidential, of course, but at some point I plan to write a separate post about some trends I’ve noticed around plagiarism and some ideas I have about how to address both its causes and its consequences. Some of what I’ve been dealing with and thinking about is addressed in

Classes have been over for a while now, but the business of the teaching term isn’t quite over. I mentioned before that one unfortunate feature of marking season is academic integrity hearings: I had more this year than I’ve ever had before, which has taken up a lot of my time and also given me a lot to think about. Individual cases are confidential, of course, but at some point I plan to write a separate post about some trends I’ve noticed around plagiarism and some ideas I have about how to address both its causes and its consequences. Some of what I’ve been dealing with and thinking about is addressed in  Since classes ended, I’ve been thinking a lot about what seemed to work and what didn’t this term. It’s always hard to know what are actual lessons about pedagogy that you can carry forward and what are idiosyncratic reactions or developments based on the specific and unpredictable population of a particular class. For instance, I thought that overall Pulp Fiction went much better this year than last. What did I do differently? Not much logistically: I used the same readings and course structure, and more or less the same assignments. Class participation was way up, though, and most of the time the atmosphere felt happier: is that because (anxious to avoid whatever went wrong last year) I tried even harder than usual to be positive, friendly, and encouraging? Did we all benefit from my having broken in this material last year and so being more adept with it this time? Or did I just get lucky and have a larger proportion of reasonably talkative students who softened the atmosphere for others to join in and thus helped increase overall engagement?

Since classes ended, I’ve been thinking a lot about what seemed to work and what didn’t this term. It’s always hard to know what are actual lessons about pedagogy that you can carry forward and what are idiosyncratic reactions or developments based on the specific and unpredictable population of a particular class. For instance, I thought that overall Pulp Fiction went much better this year than last. What did I do differently? Not much logistically: I used the same readings and course structure, and more or less the same assignments. Class participation was way up, though, and most of the time the atmosphere felt happier: is that because (anxious to avoid whatever went wrong last year) I tried even harder than usual to be positive, friendly, and encouraging? Did we all benefit from my having broken in this material last year and so being more adept with it this time? Or did I just get lucky and have a larger proportion of reasonably talkative students who softened the atmosphere for others to join in and thus helped increase overall engagement?

I have also concluded that Valdez Is Coming is not a good choice for my representative Western. When I read it on my own,

I have also concluded that Valdez Is Coming is not a good choice for my representative Western. When I read it on my own,  As for Victorian Sensations, I thought it was quite a successful seminar. Participation levels were consistently high and (as important) were of high quality; as I told the class at the end of term, I genuinely looked forward to showing up and talking with them about our readings. The only novel I hadn’t taught before was Cometh Up As A Flower; we found it provocative and sometimes puzzling, and quite a few students chose to include it in their term paper, which is a sign that they were engaged with it. It might be fun to include it in one of my standard Victorian fiction class, where it would fit well with other novels in which passion and duty collide (The Mill on the Floss, for instance), or in which the ‘romance’ of marrying for money is overtly stripped away. One slight surprise for me was that discussion flagged a bit for Fingersmith. Everyone seemed to really enjoy reading it, but it was conspicuously harder to get them to talk about it. This might have been (a bit paradoxically) because they found it fun to read and so their critical faculties shut down in ways they really can’t with a novel like East Lynne (which is pretty hard work to slog through, honestly); it might also have been that we read Fingersmith last, and by the final weeks of term everyone’s tired and overwhelmed with work.

As for Victorian Sensations, I thought it was quite a successful seminar. Participation levels were consistently high and (as important) were of high quality; as I told the class at the end of term, I genuinely looked forward to showing up and talking with them about our readings. The only novel I hadn’t taught before was Cometh Up As A Flower; we found it provocative and sometimes puzzling, and quite a few students chose to include it in their term paper, which is a sign that they were engaged with it. It might be fun to include it in one of my standard Victorian fiction class, where it would fit well with other novels in which passion and duty collide (The Mill on the Floss, for instance), or in which the ‘romance’ of marrying for money is overtly stripped away. One slight surprise for me was that discussion flagged a bit for Fingersmith. Everyone seemed to really enjoy reading it, but it was conspicuously harder to get them to talk about it. This might have been (a bit paradoxically) because they found it fun to read and so their critical faculties shut down in ways they really can’t with a novel like East Lynne (which is pretty hard work to slog through, honestly); it might also have been that we read Fingersmith last, and by the final weeks of term everyone’s tired and overwhelmed with work. Less of a surprise, but still a challenge, was how difficult it was to generate discussion on the classes I’d set aside for “critical approaches” to our novels. After the first of these sessions I realized that I needed to approach them differently, so I ran those classes more overtly than I usually do in a seminar class, adding some contextual information about the history of literary criticism and devising a set of “metacritical” discussion questions to supplement students’ questions on the specific readings. Even so, discussion was halting. I think the main reason was actually closely related to my goals for these readings. In my experience, when students read criticism they are often mining it for usable quotations, which they then drop into their own arguments as if the fact that somebody else said it proves their claim. I wanted to get them to engage with other scholars in a more equal and conversational way, learning how to see what kind of criticism they are reading (by considering its original date of publication, the venue it was published in, the kinds of questions it asks, and the kinds of evidence it considers) and then if they use it in their own work, signaling how and why in a different way. Just saying “As Critic Smartypants argues” instead of “Critic Smartypants argues” is an improvement: it implies “I’ve thought about this and agree,” not “Smartypants said it, so it’s true.”

Less of a surprise, but still a challenge, was how difficult it was to generate discussion on the classes I’d set aside for “critical approaches” to our novels. After the first of these sessions I realized that I needed to approach them differently, so I ran those classes more overtly than I usually do in a seminar class, adding some contextual information about the history of literary criticism and devising a set of “metacritical” discussion questions to supplement students’ questions on the specific readings. Even so, discussion was halting. I think the main reason was actually closely related to my goals for these readings. In my experience, when students read criticism they are often mining it for usable quotations, which they then drop into their own arguments as if the fact that somebody else said it proves their claim. I wanted to get them to engage with other scholars in a more equal and conversational way, learning how to see what kind of criticism they are reading (by considering its original date of publication, the venue it was published in, the kinds of questions it asks, and the kinds of evidence it considers) and then if they use it in their own work, signaling how and why in a different way. Just saying “As Critic Smartypants argues” instead of “Critic Smartypants argues” is an improvement: it implies “I’ve thought about this and agree,” not “Smartypants said it, so it’s true.”

Last week and this week, actually. That’s not quite all I’ve been doing since classes wrapped up on April 10: there has been a spate of committee work, and also (one of the less pleasant features of this time of term) some academic integrity hearings, which take up a fair amount of time. Then on the home front, Maddie was in her high school’s production of The Drowsy Chaperone, which had its four-performance run April 19-21, so in addition to ferrying her to and from rehearsals and doing what I could to mitigate the stress on her schedule in other ways, I’ve also been to two performances–which, on the bright side, was the most fun I’ve had in ages. (In case you know the musical, she played Mrs. Tottendale, with great comic flair. The whole cast was great, actually, as was the production, especially the costumes.)

Last week and this week, actually. That’s not quite all I’ve been doing since classes wrapped up on April 10: there has been a spate of committee work, and also (one of the less pleasant features of this time of term) some academic integrity hearings, which take up a fair amount of time. Then on the home front, Maddie was in her high school’s production of The Drowsy Chaperone, which had its four-performance run April 19-21, so in addition to ferrying her to and from rehearsals and doing what I could to mitigate the stress on her schedule in other ways, I’ve also been to two performances–which, on the bright side, was the most fun I’ve had in ages. (In case you know the musical, she played Mrs. Tottendale, with great comic flair. The whole cast was great, actually, as was the production, especially the costumes.) I’ve been too busy and distracted to settle in for any intense reading, though I did join a few Twitter friends in reading The Warden last weekend. Then I had to take all the books off my mystery bookcase (we needed to move it out of the way temporarily, to do a household project) and in the process of sorting them I was reminded how long it has been since I read most of my P. D. James collection. I’ve put An Unsuitable Job for a Woman back on the reading list for Mystery & Detective Fiction in the fall, so it seemed like a good time to revisit one or two. As a result, I’m happily rereading Death in Holy Orders, which turns out to follow very well on The Warden as it has a number of explicit references in it to Barchester Towers. James herself said she saw the 19th-century novelists as her predecessors more than the Golden Age mystery writers, and in a book like this, that genealogy is clear. There are plenty of murderous moments in Trollope but his world is (mostly) too genial a place, his morality too committed to shades of grey, to allow for outright irremediable violence. (There are exceptions, of course). Like Trollope, James is very good at depicting institutions, with all their intricate politics and emotional dynamics. She’s also exceptionally good at setting, something I emphasize when we discuss Unsuitable Job (where the beauty of Cambridge makes a poignant contrast to the horrors of the novel’s central crime). After reading several hastier or lazier stylists in this genre recently, I am appreciating the leisurely pace of her descriptions, along with the meticulous depth of her characterizations. I don’t like all of her novels equally, but when she is good, she’s very very good.

I’ve been too busy and distracted to settle in for any intense reading, though I did join a few Twitter friends in reading The Warden last weekend. Then I had to take all the books off my mystery bookcase (we needed to move it out of the way temporarily, to do a household project) and in the process of sorting them I was reminded how long it has been since I read most of my P. D. James collection. I’ve put An Unsuitable Job for a Woman back on the reading list for Mystery & Detective Fiction in the fall, so it seemed like a good time to revisit one or two. As a result, I’m happily rereading Death in Holy Orders, which turns out to follow very well on The Warden as it has a number of explicit references in it to Barchester Towers. James herself said she saw the 19th-century novelists as her predecessors more than the Golden Age mystery writers, and in a book like this, that genealogy is clear. There are plenty of murderous moments in Trollope but his world is (mostly) too genial a place, his morality too committed to shades of grey, to allow for outright irremediable violence. (There are exceptions, of course). Like Trollope, James is very good at depicting institutions, with all their intricate politics and emotional dynamics. She’s also exceptionally good at setting, something I emphasize when we discuss Unsuitable Job (where the beauty of Cambridge makes a poignant contrast to the horrors of the novel’s central crime). After reading several hastier or lazier stylists in this genre recently, I am appreciating the leisurely pace of her descriptions, along with the meticulous depth of her characterizations. I don’t like all of her novels equally, but when she is good, she’s very very good.

I am glad, therefore, that one of the tips I got on Twitter (initially from

I am glad, therefore, that one of the tips I got on Twitter (initially from  Still, my curiosity was piqued, so I decided to stop trying to figure the book out (which is a hard habit for an academic and literary critic to break!) and just browse around in it for a while to see what it might have to say to me. It turns out it did speak to me: both to the part of me that wants to, but is afraid to, put pencil to paper and draw something, but also, and perhaps more significantly, to the part of me that writes stuff. This is because Syllabus

Still, my curiosity was piqued, so I decided to stop trying to figure the book out (which is a hard habit for an academic and literary critic to break!) and just browse around in it for a while to see what it might have to say to me. It turns out it did speak to me: both to the part of me that wants to, but is afraid to, put pencil to paper and draw something, but also, and perhaps more significantly, to the part of me that writes stuff. This is because Syllabus

One particular bit from Syllabus that I know I will keep thinking about is the one I chose as my epigraph for this post, about abandoning activities we are bad at. I’ve often thought that one of the best things about advancing through life, and particularly through one’s education, is the freedom you gain to abandon things you dislike and/or aren’t good at. As I’ve often said to my own children, one of the best things about university is that you can finally choose your courses to play to your interests and strengths. It’s not that I don’t think we can get good (or at least better) at things: I wouldn’t be a teacher if I believed that! I believe in program requirements, too, because that’s how we discover what else we might be good at, or want to be good at, or just put a lot of effort into. (

One particular bit from Syllabus that I know I will keep thinking about is the one I chose as my epigraph for this post, about abandoning activities we are bad at. I’ve often thought that one of the best things about advancing through life, and particularly through one’s education, is the freedom you gain to abandon things you dislike and/or aren’t good at. As I’ve often said to my own children, one of the best things about university is that you can finally choose your courses to play to your interests and strengths. It’s not that I don’t think we can get good (or at least better) at things: I wouldn’t be a teacher if I believed that! I believe in program requirements, too, because that’s how we discover what else we might be good at, or want to be good at, or just put a lot of effort into. (

As if things in this term’s classes aren’t busy enough (and about to get busier, as next week I get in both sets of term papers and give the final exam for Pulp Fiction) but book orders for next fall were also due. It’s not a set-in-stone deadline, and quite reasonably a lot of my colleagues put it off until the summer, but I’ve actually been playing around with possible book lists for my Dickens to Hardy class since Austen to Dickens wrapped up last term, so I figured I could at least get that one settled.

As if things in this term’s classes aren’t busy enough (and about to get busier, as next week I get in both sets of term papers and give the final exam for Pulp Fiction) but book orders for next fall were also due. It’s not a set-in-stone deadline, and quite reasonably a lot of my colleagues put it off until the summer, but I’ve actually been playing around with possible book lists for my Dickens to Hardy class since Austen to Dickens wrapped up last term, so I figured I could at least get that one settled. In the end I also submitted my book order for Mystery and Detective Fiction today. If I’d waited I might have made more changes to what has become my ‘standard’ book list for the course, but though I have been considering some more recent Canadian books for inclusion, I wasn’t completely convinced either of them would work well in class (

In the end I also submitted my book order for Mystery and Detective Fiction today. If I’d waited I might have made more changes to what has become my ‘standard’ book list for the course, but though I have been considering some more recent Canadian books for inclusion, I wasn’t completely convinced either of them would work well in class ( Those are my only two courses for the fall and then I’ve got a half-year sabbatical next winter, so that’s it: my book orders for next year are done! For the first time in a long time I’m not teaching a first-year class in 2018-19. I’m glad, not because I don’t enjoy teaching introductory classes but because I want to think carefully about which one I’ll teach next, and especially about whether I’ll put in for Pulp Fiction again. We recently revised

Those are my only two courses for the fall and then I’ve got a half-year sabbatical next winter, so that’s it: my book orders for next year are done! For the first time in a long time I’m not teaching a first-year class in 2018-19. I’m glad, not because I don’t enjoy teaching introductory classes but because I want to think carefully about which one I’ll teach next, and especially about whether I’ll put in for Pulp Fiction again. We recently revised  The Honourable Schoolboy itself is anything but brief, and that turned out–more or less–to be my problem with it. Of course, I am no stranger to long books, and I would never use scale on its own as a measure of literary merit. I’m also very aware that one person’s “too long” is another person’s “wonderfully immersive” or “lavish” or whatever. The question has to be whether, for you as a reader, the pay-off is proportional, or whether the book’s scope (whether broad or narrow) is the appropriate means to its ends. George Eliot said of Middlemarch, “I don’t see how the sort of thing I want to do could have been done briefly”: I have decades of experience now at explaining why I think she’s right about that, not to mention how we can approach Middlemarch so as to appreciate how she uses all the space she claims for it. The conspicuously shorter Silas Marner, in contrast, is pretty much perfect as it is. Being long, or being short, is not in itself either a necessary or a sufficient condition for admiration or pleasure.

The Honourable Schoolboy itself is anything but brief, and that turned out–more or less–to be my problem with it. Of course, I am no stranger to long books, and I would never use scale on its own as a measure of literary merit. I’m also very aware that one person’s “too long” is another person’s “wonderfully immersive” or “lavish” or whatever. The question has to be whether, for you as a reader, the pay-off is proportional, or whether the book’s scope (whether broad or narrow) is the appropriate means to its ends. George Eliot said of Middlemarch, “I don’t see how the sort of thing I want to do could have been done briefly”: I have decades of experience now at explaining why I think she’s right about that, not to mention how we can approach Middlemarch so as to appreciate how she uses all the space she claims for it. The conspicuously shorter Silas Marner, in contrast, is pretty much perfect as it is. Being long, or being short, is not in itself either a necessary or a sufficient condition for admiration or pleasure. I can imagine that having taken these risks to get so much material, a writer would want to make use of it all! But maybe that personal investment also worked against him, making him reluctant to leave anything out, or unable to choose between what he knew and what his story actually needed.

I can imagine that having taken these risks to get so much material, a writer would want to make use of it all! But maybe that personal investment also worked against him, making him reluctant to leave anything out, or unable to choose between what he knew and what his story actually needed. The other thing I really liked about The Honourable Schoolboy is Le Carré’s prose–which might seem contradictory, given my complaints about the novel’s length, but that just goes to show that good writing isn’t everything! Here’s just one example of the kind of sharply evocative description that is over-abundant in the novel:

The other thing I really liked about The Honourable Schoolboy is Le Carré’s prose–which might seem contradictory, given my complaints about the novel’s length, but that just goes to show that good writing isn’t everything! Here’s just one example of the kind of sharply evocative description that is over-abundant in the novel: