I have heard the melody in the heart of the universe and then lost it.

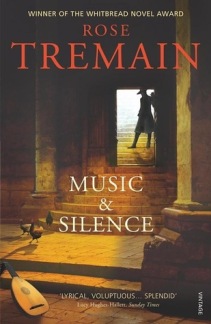

Like Restoration, Rose Tremain’s Music & Silence confounds clichéd expectations about historical fiction. In its own way it has an epic sweep, but there’s nothing of the heroic saga about it. It’s drama under a blanket, a story of kings and queens and true love muffled by darkness and uncertainty. It has the extremity of fairy tales: Kirsten Munk, for instance, consort to King Christian and thus “Almost Queen” of Denmark, is a temperamentally oversized creature of voracious, noisy demands: her first-person portions of the narrative would be wholly comical if they weren’t also so sad, and if she weren’t also so destructive in her relentlessly selfish desires. Kirsten has a near counterpart in Magdalena, the wicked stepmother who forces the Cinderella-like heroine Emilia out of the family and then, insatiably needy, seduces her step-sons.

Like Restoration, Rose Tremain’s Music & Silence confounds clichéd expectations about historical fiction. In its own way it has an epic sweep, but there’s nothing of the heroic saga about it. It’s drama under a blanket, a story of kings and queens and true love muffled by darkness and uncertainty. It has the extremity of fairy tales: Kirsten Munk, for instance, consort to King Christian and thus “Almost Queen” of Denmark, is a temperamentally oversized creature of voracious, noisy demands: her first-person portions of the narrative would be wholly comical if they weren’t also so sad, and if she weren’t also so destructive in her relentlessly selfish desires. Kirsten has a near counterpart in Magdalena, the wicked stepmother who forces the Cinderella-like heroine Emilia out of the family and then, insatiably needy, seduces her step-sons.

In contrast to their hot, vociferous passions, there’s Emilia, quiet, grave, nurturing — and otherworldly, drawn, nearly out of life itself, to her dead mother’s memory. And there’s the beautiful Countess O’Fingal, beautiful, loving, but trapped by her husband’s tragedy, which is like an evil curse disguised as a blessing:

Johnnie O’Fingal had dreamed that he could compose music. In this miraculous reverie, he had gone down to the hall, where resided a pair of virginals . . . and had sat down in front of them and taken up a piece of my father’s cream paper and a newly cut quill. In frantic haste, he had ruled the lines of the treble and bass clef, and begun immediately upon a complicated musical notation, corresponding to sounds and harmonies that flowed effortlessly from his mind onto the page. And when he began to play the music he had written it was a lament of such grace and beauty that he did not think he had ever heard in his life anything to match it.

Urged by his wife to recapture the music of his dreams, he declares prophetically, “what we can achieve in our dreams seldom corresponds to what we are veritably capable of.” He does try, playing “a melody of strange and haunting sweetness,” but goes mad in grief and despair when he is never able to complete it. His desperate quest (and its painfully ironic ending) echoes that of King Christian, who has all the music he desires but is unable to bring order and prosperity to his kingdom, or to find lasting love and comfort for himself.

Yoking their stories together is the figure of Peter Claire, a lutenist so beautiful Christian calls him his angel. It seems as if Peter’s music should be the salvation both other men seek — throughout the novel music is at once the greatest mystery and the greatest joy anyone experiences. Christian tells Peter about a conversation he had with the great musician John Dowland:

He said that man spends days and nights and years of his life asking the question “How may I be brought to the divine?”, yet all musicians instinctively know the answer: they are brought to the divine through their music – for this is its sole purpose. Its sole purpose! What do you say to that, Mr Claire?

But though Peter cherishes the “rich and faultless harmony” he and the rest of King Christian’s orchestra create from their strange subterranean quarters — the King has contrived it so that the sound is carried up into the castle for the pleasure but also mystification of his guests, who cannot detect its source — his own “transcendent state of happiness” comes from his love for Emilia. The novel is in part the story of their romance, fragile, insubstantial, thwarted by Kirsten’s greed and Christian’s need. The interplay of these characters is much more complex than simple antagonism, though: Peter and Emilia are hampered by their kindness and empathy as much as by any external constraints. The price of goodness, in their world, is as likely to be loss as reward.

There are other characters and story-lines in the novel; I found their interweaving equal parts engaging and annoying, as the result is somewhat fragmented but also invites us — as literary juxtapositions always do — to think about connections and comparisons, themes and variations. It isn’t entirely obvious to me what unifies the different elements. In the end I wonder if it’s primarily a mood or an attitude that we’re supposed to take away from our reading — a sense of what the world might be like rather than a coherent idea about what it is or should be like. The atmosphere of the book is slightly surreal, and the tone walks a fine line between being poetic and being portentous, or even pretentious. Tremain’s language falls into rhythmic cadences that shift us from the prosaic to the visionary:

Now, Emilia lies in her old bed in her old room and listens to the old familiar crying of the wind.

By her bed is the clock she found in the forest, with time stopped at ten minutes past seven.

She does not know why Magdalena was locked in the attic.

She does not know why Ingmar was sent to Copenhagen.

She cannot predict what world Marcus will enter now.

What she does know is that time itself has performed a loop and returned her to the one place she thought she had left for ever. It has stopped here and will not let her go. . . . She will grow old in the house of her childhood, without her mother, without her father’s love. She will die here and one of her brothers will bury her in the shadow of the church, and the strawberry plants, which creep further and wider each year, gobbling up the land, even to the church door, will one day cover everything that remains of her, including her name, Emilia.

I wouldn’t want to read a lot of books written this way, or any at all written this way without the other qualities Tremain brings to it: intensely tactile historical specificity, for one thing, and an unswerving commitment to the flawed humanity of even her most grotesque characters. If Music & Silence is a fairy tale in style, I think it is, paradoxically, still a realist novel in spirit. If it has a message for us about music and silence, also, it is not that they are opposites but that (like imagination and reality) they are somehow inextricably linked, two aspects of the same attempt to express something important about life. This is something the characters are always experiencing, one way or another — that the actual sounds they can make do not quite convey the ideas and feelings they have, that their longings and loves and fears and hatreds shape their lives but are hard to give shape to in sound:

As they part, both men reflect on all that might have been said in this recent conversation and yet was not said; and this knowledge of what so often exists in the silences between words both haunts them and makes them marvel at the teasing complexity of all human discourse.

Very interesting review. I think this is a style which is unduly popular as it is very hard to carry off without dissolving into breathless romanticism or soggy lyricism. I have more faith in Rose Tremain than a lot of other authors to get away with it! I like what you say about music and silence. I used to tell my students that they should pay attention to the silence in novels because if a book fell obviously silent, something terrifically important was going on. Or perhaps it’s less gnomic to say that silence in books is where the reader gets to do a lot of imaginative work. I’d like to read this novel – but not right at the moment!

LikeLike

I agree with you about the risks of this — elevated? mannered? conspicuously artful? — style. In the wrong hands it comes across as simply intrusive. The last book I read that I thought pulled it off was Mark Helprin’s In Sunlight and In Shadow (which is in other respects a very different novel).

LikeLike

It’s interesting that of all Tremain’s books this is the one that has stayed with me least and even reading your review hasn’t really brought it back to me as I would have expected. I would like to put it back on the reading pile simply to see what that might be but unfortunately, at the moment, that would cause an avalanche.

LikeLike

Have you read the recent sequel to Restoration? I am tempted, but I did find this one a bit slow going, so I think I’m going to put it off until things quiet down. Maybe I’ll put it on my Christmas wish list… So far these are the only two of hers that I’ve read. Do you have a favorite?

LikeLike