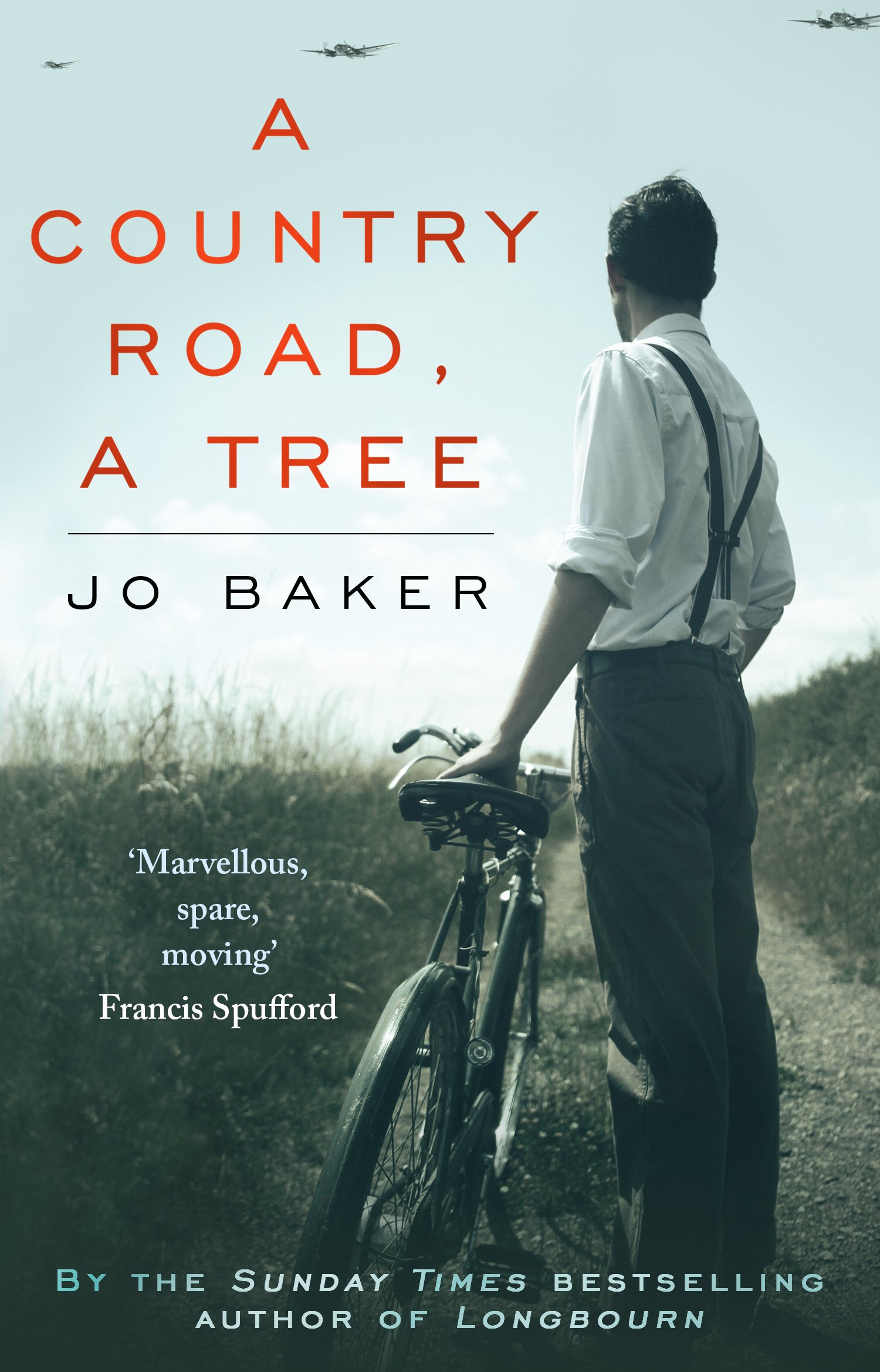

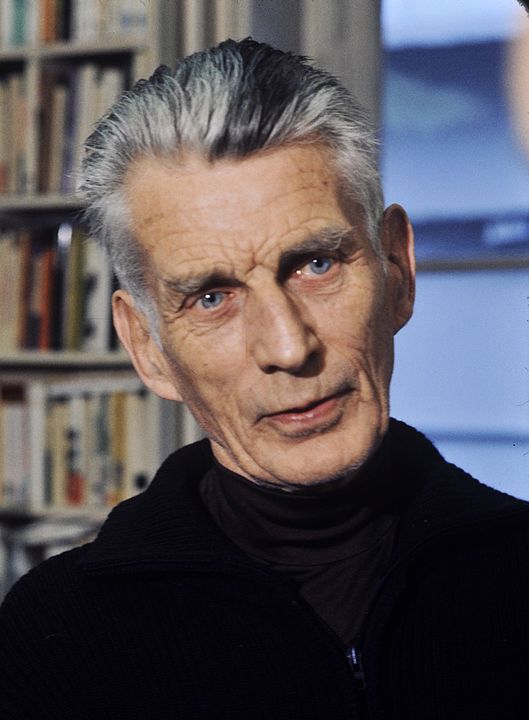

My near total first-hand ignorance of Samuel Beckett’s work would probably be a real advantage to me in David Lodge’s famous game ‘Humiliation.’ Even my second-hand knowledge is pretty limited: I have a casual idea of what Waiting for Godot is like and about, and that’s it. As with all novels steeped in another author’s lives and ideas, Jo Baker’s A Country Road, A Tree is probably better appreciated by someone else, then, someone who can do more than stumble over a reference to an ‘endgame’ and think “hey, that’s probably an allusion!” or who can read Baker’s moving description of Beckett’s epiphany about his own writing and really understand what it meant in practice:

My near total first-hand ignorance of Samuel Beckett’s work would probably be a real advantage to me in David Lodge’s famous game ‘Humiliation.’ Even my second-hand knowledge is pretty limited: I have a casual idea of what Waiting for Godot is like and about, and that’s it. As with all novels steeped in another author’s lives and ideas, Jo Baker’s A Country Road, A Tree is probably better appreciated by someone else, then, someone who can do more than stumble over a reference to an ‘endgame’ and think “hey, that’s probably an allusion!” or who can read Baker’s moving description of Beckett’s epiphany about his own writing and really understand what it meant in practice:

There is nothing grand about it; no waves, no wind, no briny spray. The world is not and never was in sympathy with him, nor with anybody else. But this is the moment when everything changes, the moment when the wide chaotic chatter and stink of it, all that wild Shem-beloved hubbub, falls away, and his eyes are trained on darkness and his ears on silence. On that stark figure, framed there on the threshold, unknowable, and his.

By this point in Baker’s novel, though, I did at least know enough about Beckett (or, about her version of Beckett) to recognize the importance of this moment as a break away from the brooding and now posthumous influence of James Joyce (“Shem”), whom Beckett assisted and idolized. “Oh you poor thing,” his friend Anna Beamish exclaims when he tells her that he helped Joyce with Finnegans Wake; “Being friends with a genius.”

Throughout A Country Road, A Tree Beckett is trying—wracked with self-doubt and haunted by the oddity of writing at all in the midst of calamity and danger—to figure out how to write his way:

He stares now at the three words he has written. They are ridiculous. Writing is ridiculous. A sentence, any sentence, is absurd. Just the idea of it: jam one word up against another, shoulder-to-shoulder, jaw-to-jaw; hem them in with punctuation so they can’t move an inch. And then hand that over to someone else to peer at, and expect something to be communicated, something understood. It’s not just pointless. It is ethically suspect.

When it’s possible, writing is an escape for him, a source of clarity and comfort, but when the spell breaks, the results bring him little satisfaction:

even to have written this little is an excess, it is an overflowing, an excretion. Too many words. There are just too many words. Nobody wants them, nobody needs them. And still they keep on, keep on, keep on coming.

This revulsion against excess is what underlies that later moment of revelation, which Baker explains further in her Author’s Note:

[The wartime years] marked the start of his paring away at language: a stripping-back of Joycean wordplay and polyphonic extravagance, towards bare bones, and silence.

Baker’s own prose in this novel strikes me as cautiously influenced by that model of “paring away,” though in that respect A Country Road, A Tree isn’t really different from a lot of conspicuously well-crafted recent novels. It is not quite as spare as Normal People, and Baker is particularly good at scene setting with concrete details and vivid imagery: the novel definitely invites the over-used term “atmospheric.” But there is little exposition; the action and dialogue do most of the work.

The specific scenes that need setting are those of Beckett’s years in occupied France, during which he played a part (a small part, he insisted) in the French Resistance. I didn’t know that this was part of Beckett’s story. Anyone’s experience of this kind would make a compelling novel (and of course there have been many other books of one kind or another about this period), and Baker does a really good job conveying the anxiety of it all: it’s an extremely tense narrative, especially from the first moment Beckett joins in with the resistance efforts. The vicarious pressure of living in constant fear of exposure or betrayal, and then with the immediate hazards of escape and living in hiding, was almost too much to add to my own currently high levels of anxiety as the third COVID wave hits Halifax and once again everyday activities feel fraught with risk. In fact, a lot about A Country Road, A Tree felt timely, as something Baker’s Beckett is particularly attuned to is the disorientation induced by the ways crisis defamiliarizes even our most routine activities and intimate spaces.

The specific scenes that need setting are those of Beckett’s years in occupied France, during which he played a part (a small part, he insisted) in the French Resistance. I didn’t know that this was part of Beckett’s story. Anyone’s experience of this kind would make a compelling novel (and of course there have been many other books of one kind or another about this period), and Baker does a really good job conveying the anxiety of it all: it’s an extremely tense narrative, especially from the first moment Beckett joins in with the resistance efforts. The vicarious pressure of living in constant fear of exposure or betrayal, and then with the immediate hazards of escape and living in hiding, was almost too much to add to my own currently high levels of anxiety as the third COVID wave hits Halifax and once again everyday activities feel fraught with risk. In fact, a lot about A Country Road, A Tree felt timely, as something Baker’s Beckett is particularly attuned to is the disorientation induced by the ways crisis defamiliarizes even our most routine activities and intimate spaces.

Following Beckett’s own lead, Baker never glamorizes Beckett’s resistance work; she doesn’t even treat it as particularly heroic. It’s true that, in retrospect at least, he came through it all pretty well, better than many of his collaborators in these efforts not to mention many, many other people. In the end what’s interesting and important about this particular story about that time and that work is what it meant to Beckett as a writer: that’s really what A Country Road, A Tree is about. Does that trivialize the war, the resistance, the deaths and suffering? I don’t think so. Beckett did more than many of us would to push back against evil, but that wasn’t his chosen work, and it seems right to pay attention to what he made of that experience, or what that experience meant to him, when its imperatives lifted and he was once again able to create unimpeded–or, at any rate, unimpeded by quite the same array of external crises. We shouldn’t let war (or COVID) convince us that things not obviously or directly related to them are not important, that the right response is to marginalize or pare away things we genuinely value. Apparently Churchill’s line about preserving the arts (“then what are we fighting for?”) is apocryphal, something he never said, but the sentiment it expresses is surely true, or at least a lot of us agree with it. To think that Beckett’s writing is less important than his efforts against the Nazis is, in a way, to lose the war. (I have questions like this about what really matters during a crisis in mind because it’s part of what I decided to write about in the essay I’ve been working on about The Balkan Trilogy—out soon, I hope.)

Following Beckett’s own lead, Baker never glamorizes Beckett’s resistance work; she doesn’t even treat it as particularly heroic. It’s true that, in retrospect at least, he came through it all pretty well, better than many of his collaborators in these efforts not to mention many, many other people. In the end what’s interesting and important about this particular story about that time and that work is what it meant to Beckett as a writer: that’s really what A Country Road, A Tree is about. Does that trivialize the war, the resistance, the deaths and suffering? I don’t think so. Beckett did more than many of us would to push back against evil, but that wasn’t his chosen work, and it seems right to pay attention to what he made of that experience, or what that experience meant to him, when its imperatives lifted and he was once again able to create unimpeded–or, at any rate, unimpeded by quite the same array of external crises. We shouldn’t let war (or COVID) convince us that things not obviously or directly related to them are not important, that the right response is to marginalize or pare away things we genuinely value. Apparently Churchill’s line about preserving the arts (“then what are we fighting for?”) is apocryphal, something he never said, but the sentiment it expresses is surely true, or at least a lot of us agree with it. To think that Beckett’s writing is less important than his efforts against the Nazis is, in a way, to lose the war. (I have questions like this about what really matters during a crisis in mind because it’s part of what I decided to write about in the essay I’ve been working on about The Balkan Trilogy—out soon, I hope.)  And it is probably in this case best, anyway, not to consider these things as in opposition. Writers’ experiences become their art, and that’s what Baker is primarily exploring: how being alone and afraid and constantly confronted with irrationality and violence and threats both literal and existential brought Beckett to an understanding of what he wanted to write and how.

And it is probably in this case best, anyway, not to consider these things as in opposition. Writers’ experiences become their art, and that’s what Baker is primarily exploring: how being alone and afraid and constantly confronted with irrationality and violence and threats both literal and existential brought Beckett to an understanding of what he wanted to write and how.

I think one reason I hadn’t pursued any further information about or experience of Beckett was that what I (vaguely) thought I knew about Waiting for Godot made me think I’d find his work both confusing and kind of depressing. Baker’s novel showed me something more appealing—not easy answers about “the meaning of life” or uplifting stories of courage under fire, but reasons for the kind of quiet optimism that depends on just doing the best we can:

Things are getting better. Things are becoming sound. There’s asphalt on the roads and on the paths. There’s glass, or something like glass, in all the windows. There’s lino on the labour-room floor—since there is breeding still, even now, even in this devastation. There are curtains round the beds, and clean sheets and warm blankets neatly tucked in. . . There is tea and there are biscuits and there is bread-and-jam when it is required, and it is often required. There’s kindness here. There’s decency among the ruins. It is something to behold.

I gazed up at the sky and let my eyes flicker from one constellation to another to another, jumping between stepping-stones. I thought of the heavenly bodies throwing down their narrow ropes of light to hook us.

I gazed up at the sky and let my eyes flicker from one constellation to another to another, jumping between stepping-stones. I thought of the heavenly bodies throwing down their narrow ropes of light to hook us. Unfortunately, The Pull of the Stars is the least fine of the ones I’ve read: though I was gripped by it at first, by the end I found it quite disappointing. The ingredients are excellent, Donoghue’s research was obviously meticulous, and some moments are really memorable, but as a whole, it just doesn’t work very well. The premise is simple and promising: the novel covers three intense days in a Dublin maternity ward during the 1918 flu pandemic. It follows the grueling and often heroic exertions of Nurse Julia Power, her feisty volunteer assistant Bridie Sweeney, and Dr. Kathleen Lynn, an actual historical person who (among other things) was active in Sinn Féin and a fierce advocate for “nutrition, housing, and sanitation for her fellow citizens” (from Donoghue’s Author’s Note). The graphic descriptions of medical crises and procedures–whether for symptoms of influenza or for childbirth–make for grim reading that’s often really absorbing, in a documentary sort of way. Here’s a representative sample:

Unfortunately, The Pull of the Stars is the least fine of the ones I’ve read: though I was gripped by it at first, by the end I found it quite disappointing. The ingredients are excellent, Donoghue’s research was obviously meticulous, and some moments are really memorable, but as a whole, it just doesn’t work very well. The premise is simple and promising: the novel covers three intense days in a Dublin maternity ward during the 1918 flu pandemic. It follows the grueling and often heroic exertions of Nurse Julia Power, her feisty volunteer assistant Bridie Sweeney, and Dr. Kathleen Lynn, an actual historical person who (among other things) was active in Sinn Féin and a fierce advocate for “nutrition, housing, and sanitation for her fellow citizens” (from Donoghue’s Author’s Note). The graphic descriptions of medical crises and procedures–whether for symptoms of influenza or for childbirth–make for grim reading that’s often really absorbing, in a documentary sort of way. Here’s a representative sample: Assuming you have the stomach for this kind of stuff, and also assuming you have the emotional fortitude to persist with a novel about a pandemic while in the midst of one (that was a close call for me)–if neither of those aspects of The Pull of the Stars puts you off, then what’s not to like? Well, of course you might like it just fine! My complaint is that for most of the book, there’s almost no story, no plot: it’s just a sequence of events. The only shape the narrative has is linear: things happen, one after another, and our small cast of characters reacts, but moving on to the next thing is not the same as going anywhere. Maybe that was a deliberate formal choice, as Julia herself resists the idea that people’s lives have direction or meaning, but for me it made the first three quarters of the novel feel aimless, with no sense that its parts were turning into anything. Then the novel became a love story, a development which seemed so abrupt it felt like an afterthought: there was no groundwork laid for it, no anticipation of it, no thematic reason for it. And then, just as abruptly, the love story [SPOILER ALERT] turns to tragedy, and while we know by then that the influenza can progress with appalling speed, still, it felt unfortunately pat as a way to wrap things up.

Assuming you have the stomach for this kind of stuff, and also assuming you have the emotional fortitude to persist with a novel about a pandemic while in the midst of one (that was a close call for me)–if neither of those aspects of The Pull of the Stars puts you off, then what’s not to like? Well, of course you might like it just fine! My complaint is that for most of the book, there’s almost no story, no plot: it’s just a sequence of events. The only shape the narrative has is linear: things happen, one after another, and our small cast of characters reacts, but moving on to the next thing is not the same as going anywhere. Maybe that was a deliberate formal choice, as Julia herself resists the idea that people’s lives have direction or meaning, but for me it made the first three quarters of the novel feel aimless, with no sense that its parts were turning into anything. Then the novel became a love story, a development which seemed so abrupt it felt like an afterthought: there was no groundwork laid for it, no anticipation of it, no thematic reason for it. And then, just as abruptly, the love story [SPOILER ALERT] turns to tragedy, and while we know by then that the influenza can progress with appalling speed, still, it felt unfortunately pat as a way to wrap things up. There are some other threads of interest in the novel, including scathing critiques of the nuns and the abusive girls’ “homes” they run, and Dr. Lynn provides occasions for some bits of political back and forth. Again, these are good ingredients (especially Dr. Lynn, whose biography Kathleen Lynn: Irishwoman, Patriot, Doctor sounds well worth reading), but I like a novel to feel, by the end, like something significantly more than the sum of its parts, and I don’t think The Pull of the Stars pulled that off, even though Donoghue joins all the dots neatly enough. If for some reason you are actually in the mood for a novel about the plague, I would recommend reading

There are some other threads of interest in the novel, including scathing critiques of the nuns and the abusive girls’ “homes” they run, and Dr. Lynn provides occasions for some bits of political back and forth. Again, these are good ingredients (especially Dr. Lynn, whose biography Kathleen Lynn: Irishwoman, Patriot, Doctor sounds well worth reading), but I like a novel to feel, by the end, like something significantly more than the sum of its parts, and I don’t think The Pull of the Stars pulled that off, even though Donoghue joins all the dots neatly enough. If for some reason you are actually in the mood for a novel about the plague, I would recommend reading

The result is delightful but (perhaps inevitably) also sort of silly. The incongruity of dragons behaving exactly like Trollope characters is sometimes hilarious and sometimes (for me at least) too much: references to their swirling eyes and burnished scales and “beds” of gold coins made it hard for me to engage with them as characters with the usual kinds of motives and feelings. But there’s also something slyly thought-provoking in Walton’s literalization of the inequalities and hang-ups of the period – or, probably more accurately, of the novels of the period. One clever aspect of Tooth and Claw, for example, is that the female dragons “pink up” when in love – though they may also, and this proves problematic, pink up when approached too closely even by a male they don’t love, and that can have serious consequences for their reputations. It is both appropriate and necessary for female dragons to react this way to their potential spouse – and once married they turn increasingly rosy, a sign of their sexual maturity. Any reader of Victorian novels is familiar with the novelists’ trick of having heroines blush as a delicate sign of sexual attraction or arousal, and also with the impossible trick these heroines are supposed to perform of never desiring except where and when it’s acceptable, staying ignorant and virtuous until the switch is flipped and they go from innocent girl to bride, wife, and mother (and thus, implicitly but by definition sexually active). Navigating this terrain is treacherous for both the heroines themselves and their authors; reconciling sexuality and propriety or principle is a key theme of 19th-century novelists from Austen to Hardy and Gissing. Walton’s spin on this doesn’t tell us anything about it that her Victorian predecessors haven’t explored already, but it’s still ingenious and amusing to follow.

The result is delightful but (perhaps inevitably) also sort of silly. The incongruity of dragons behaving exactly like Trollope characters is sometimes hilarious and sometimes (for me at least) too much: references to their swirling eyes and burnished scales and “beds” of gold coins made it hard for me to engage with them as characters with the usual kinds of motives and feelings. But there’s also something slyly thought-provoking in Walton’s literalization of the inequalities and hang-ups of the period – or, probably more accurately, of the novels of the period. One clever aspect of Tooth and Claw, for example, is that the female dragons “pink up” when in love – though they may also, and this proves problematic, pink up when approached too closely even by a male they don’t love, and that can have serious consequences for their reputations. It is both appropriate and necessary for female dragons to react this way to their potential spouse – and once married they turn increasingly rosy, a sign of their sexual maturity. Any reader of Victorian novels is familiar with the novelists’ trick of having heroines blush as a delicate sign of sexual attraction or arousal, and also with the impossible trick these heroines are supposed to perform of never desiring except where and when it’s acceptable, staying ignorant and virtuous until the switch is flipped and they go from innocent girl to bride, wife, and mother (and thus, implicitly but by definition sexually active). Navigating this terrain is treacherous for both the heroines themselves and their authors; reconciling sexuality and propriety or principle is a key theme of 19th-century novelists from Austen to Hardy and Gissing. Walton’s spin on this doesn’t tell us anything about it that her Victorian predecessors haven’t explored already, but it’s still ingenious and amusing to follow. Another smart aspect of Tooth and Claw is its attention to the ways wealth is hoarded and shared (or not shared), so that the powerful elite not only maintain their status but expand it, while the weaker and more vulnerable compete (quite literally) for the scraps. When a dragon dies, for instance, its heirs eat it, their shares apportioned by custom and privilege. Eating a dragon makes the consuming dragon bigger and stronger: thus the laws of inheritance perpetuate inequality. Weakling members of families are also eaten, thus guaranteeing the greater size and strength of the survivors (hello, Darwin); servants who have outlived their usefulness are eaten – and so too, sometimes, are servants who disobey or betray the family they serve. Legal disputes can be settled by combat, with the loser getting eaten – which would certainly have had implications for Jarndyce v. Jarndyce! Again, it’s ingenious, a dynamic of competition and entitlement familiar to readers of Trollope but shown up as more ruthless than Trollope’s gentle satire typically acknowledges.

Another smart aspect of Tooth and Claw is its attention to the ways wealth is hoarded and shared (or not shared), so that the powerful elite not only maintain their status but expand it, while the weaker and more vulnerable compete (quite literally) for the scraps. When a dragon dies, for instance, its heirs eat it, their shares apportioned by custom and privilege. Eating a dragon makes the consuming dragon bigger and stronger: thus the laws of inheritance perpetuate inequality. Weakling members of families are also eaten, thus guaranteeing the greater size and strength of the survivors (hello, Darwin); servants who have outlived their usefulness are eaten – and so too, sometimes, are servants who disobey or betray the family they serve. Legal disputes can be settled by combat, with the loser getting eaten – which would certainly have had implications for Jarndyce v. Jarndyce! Again, it’s ingenious, a dynamic of competition and entitlement familiar to readers of Trollope but shown up as more ruthless than Trollope’s gentle satire typically acknowledges. I don’t think Tooth and Claw is more revealing or insightful, or more critical, about Victorian society than the actual Victorian novelists I know best, but Walton’s novel is a lot of fun to read: it is satisfying in the way that watching any highly original concept be executed well is satisfying. I found it thoroughly entertaining. Her dragons are fearsome but also pretty lovable; she finds a way to make “mellow music” with them. Unlike one of the reviewers quoted on the cover, I didn’t finish it “wishing it were twice as long,” but Framley Parsonage is twice as long and more, and Tooth and Claw did make me think it might be time to reread it.

I don’t think Tooth and Claw is more revealing or insightful, or more critical, about Victorian society than the actual Victorian novelists I know best, but Walton’s novel is a lot of fun to read: it is satisfying in the way that watching any highly original concept be executed well is satisfying. I found it thoroughly entertaining. Her dragons are fearsome but also pretty lovable; she finds a way to make “mellow music” with them. Unlike one of the reviewers quoted on the cover, I didn’t finish it “wishing it were twice as long,” but Framley Parsonage is twice as long and more, and Tooth and Claw did make me think it might be time to reread it. At the moment the only topic she could discuss was herself. And everyone, she felt, had heard enough about her. They believed it was time that she stop brooding and think of other things. But there were no other things. There was only what had happened. It was as though she lived underwater and had given up on the struggle to swim towards air. It would be too much. Being released into the world of others seemed impossible; it was something she did not even want.

At the moment the only topic she could discuss was herself. And everyone, she felt, had heard enough about her. They believed it was time that she stop brooding and think of other things. But there were no other things. There was only what had happened. It was as though she lived underwater and had given up on the struggle to swim towards air. It would be too much. Being released into the world of others seemed impossible; it was something she did not even want. More than that, it felt to me that Nora Webster uses that characteristic stillness of Tóibín’s in a meaningful way: to reflect Nora’s own emotional state, her feeling that she is both unable and unwilling to rise to the surface and meet the demands and expectations of those around her. It’s her situation that is the cause of her repression, not her character (as is the case in Brooklyn), and so there is more tension behind Tóibín’s precise prose because we see signs of her potential for fierceness even before she begins to recover and show more of it herself. Waiting to see when and how she would break through was interesting in a way that (for me) Brooklyn was not. As the novel went on, I was rooting for Nora to be more and do more, to allow herself to feel; I enjoyed her displays of strength, which made clear that it’s her grief, not Nora herself, that is the problem.

More than that, it felt to me that Nora Webster uses that characteristic stillness of Tóibín’s in a meaningful way: to reflect Nora’s own emotional state, her feeling that she is both unable and unwilling to rise to the surface and meet the demands and expectations of those around her. It’s her situation that is the cause of her repression, not her character (as is the case in Brooklyn), and so there is more tension behind Tóibín’s precise prose because we see signs of her potential for fierceness even before she begins to recover and show more of it herself. Waiting to see when and how she would break through was interesting in a way that (for me) Brooklyn was not. As the novel went on, I was rooting for Nora to be more and do more, to allow herself to feel; I enjoyed her displays of strength, which made clear that it’s her grief, not Nora herself, that is the problem.  I particularly liked the way the novel used music as Nora’s way back. It’s hard to write well about music. I think Lynn Sharon Schwartz does it wonderfully in

I particularly liked the way the novel used music as Nora’s way back. It’s hard to write well about music. I think Lynn Sharon Schwartz does it wonderfully in  Once several years ago I was waiting for my daughter to come out of a medical appointment. The waiting area was, as is typical, neither particularly comfortable nor particularly cheering, and yet when she came out she stopped and exclaimed “you look so happy!” And I was! Why? Because I had just been reading the part of Georgette Heyer’s Devil’s Cub in which (if you know the novel, you can probably already guess) our heroine Mary accidentally tells the forbidding Duke of Avon all about the troubles she has been having with his renegade son, the Marquis of Vidal, with whom she has, against all propriety and practicality, fallen completely in love. I say “accidentally” because she doesn’t know that the enigmatic man she’s talking to is Vidal’s father–but we do, or at least we suspect it much sooner than she discovers it, and so the whole conversation is just delicious, for reasons you have to read the rest of the novel to fully appreciate.

Once several years ago I was waiting for my daughter to come out of a medical appointment. The waiting area was, as is typical, neither particularly comfortable nor particularly cheering, and yet when she came out she stopped and exclaimed “you look so happy!” And I was! Why? Because I had just been reading the part of Georgette Heyer’s Devil’s Cub in which (if you know the novel, you can probably already guess) our heroine Mary accidentally tells the forbidding Duke of Avon all about the troubles she has been having with his renegade son, the Marquis of Vidal, with whom she has, against all propriety and practicality, fallen completely in love. I say “accidentally” because she doesn’t know that the enigmatic man she’s talking to is Vidal’s father–but we do, or at least we suspect it much sooner than she discovers it, and so the whole conversation is just delicious, for reasons you have to read the rest of the novel to fully appreciate. Last week, because the new books I had been reading weren’t thrilling me, I decided to reread an old favorite, Dorothy Dunnett’s The Ringed Castle. I know this novel so well now that sometimes I skim a bit to get to the parts I particularly love. I read quite a bit of it ‘properly’ this time, because it’s just so good, and it helped reconnect me with my inner bookworm. Near the end, there’s a scene in The Ringed Castle that makes me just as happy as that bit of Devil’s Cub (again, readers of the novel can probably guess which one – in fact, when I mentioned this on Twitter

Last week, because the new books I had been reading weren’t thrilling me, I decided to reread an old favorite, Dorothy Dunnett’s The Ringed Castle. I know this novel so well now that sometimes I skim a bit to get to the parts I particularly love. I read quite a bit of it ‘properly’ this time, because it’s just so good, and it helped reconnect me with my inner bookworm. Near the end, there’s a scene in The Ringed Castle that makes me just as happy as that bit of Devil’s Cub (again, readers of the novel can probably guess which one – in fact, when I mentioned this on Twitter  “You look so happy”: that’s not the only thing reading can do, and it isn’t always what we want from our reading, but it’s a special gift when it happens, isn’t it, especially these days? I can think of only a few other scenes that have this particular effect on me: the bathing scene in A Room with a View, the evidence-collecting walk on the beach in Have His Carcase, the rooftop chase in Checkmate (so, score two for Dunnett), the ending of Pride and Prejudice, several small pieces of Cranford (the cow in flannel pyjamas!). Of course there are many, many other reading moments that I love and enjoy and return to over and over, for all sorts of reasons, but these are the some of the ones that make me feel as if I’ve turned my face to the sun: warmed, uplifted, delighted. The joy they give me depends not just on the words on the page but on my history with those pages, and also, as with all idiosyncratic responses, on my own history more generally, and on that elusive thing we could call my “sensibility” as a reader. In that moment everything, not just reading, feels as good as it gets. What a comfort it always is to know that I can return to that happy place any time, just by picking the book up again.

“You look so happy”: that’s not the only thing reading can do, and it isn’t always what we want from our reading, but it’s a special gift when it happens, isn’t it, especially these days? I can think of only a few other scenes that have this particular effect on me: the bathing scene in A Room with a View, the evidence-collecting walk on the beach in Have His Carcase, the rooftop chase in Checkmate (so, score two for Dunnett), the ending of Pride and Prejudice, several small pieces of Cranford (the cow in flannel pyjamas!). Of course there are many, many other reading moments that I love and enjoy and return to over and over, for all sorts of reasons, but these are the some of the ones that make me feel as if I’ve turned my face to the sun: warmed, uplifted, delighted. The joy they give me depends not just on the words on the page but on my history with those pages, and also, as with all idiosyncratic responses, on my own history more generally, and on that elusive thing we could call my “sensibility” as a reader. In that moment everything, not just reading, feels as good as it gets. What a comfort it always is to know that I can return to that happy place any time, just by picking the book up again.

I can’t post about books I’ve finished this week because I haven’t finished any. I’ve been trying to read–keeping in mind

I can’t post about books I’ve finished this week because I haven’t finished any. I’ve been trying to read–keeping in mind  So, one challenge is aging, and there’s not much to be done about that (and it’s only going to get worse, I know!) The other, though, has been the books I’ve been trying to focus on. Both are ones I have wanted to read for a long time, but neither has proved the right book for this moment, although one of them I am still working on. The first one I started this week was Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, which has been on my reading wish list for years. It looks great! I am sure it is great! But a couple of chapters into it, I just couldn’t bear it: it was making me feel both bored and claustrophobic. I suspect some of that is a deliberate effect, as it seems to be about a stifling world that tries to stifle people’s feelings. Bowen’s sentences didn’t help. I love Olivia Manning’s description of Bowen’s prose as being like someone drinking milk with their legs crossed behind their head: often, it just seems to be making something that’s actually fairly simple much more complicated than it needs to be!

So, one challenge is aging, and there’s not much to be done about that (and it’s only going to get worse, I know!) The other, though, has been the books I’ve been trying to focus on. Both are ones I have wanted to read for a long time, but neither has proved the right book for this moment, although one of them I am still working on. The first one I started this week was Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, which has been on my reading wish list for years. It looks great! I am sure it is great! But a couple of chapters into it, I just couldn’t bear it: it was making me feel both bored and claustrophobic. I suspect some of that is a deliberate effect, as it seems to be about a stifling world that tries to stifle people’s feelings. Bowen’s sentences didn’t help. I love Olivia Manning’s description of Bowen’s prose as being like someone drinking milk with their legs crossed behind their head: often, it just seems to be making something that’s actually fairly simple much more complicated than it needs to be!  The other is John Le Carré’s A Perfect Spy, which I am still working on. I loved

The other is John Le Carré’s A Perfect Spy, which I am still working on. I loved  So that’s where I am this week! I have been thinking a lot about posting more in my once-usual “this week in my classes” series but I can’t seem to get past the twin obstacles of my classes

So that’s where I am this week! I have been thinking a lot about posting more in my once-usual “this week in my classes” series but I can’t seem to get past the twin obstacles of my classes  I continued trying harder this week to do better reading, choosing books that I hoped would bring more or different rewards than my recent rather desultory choices of mysteries and romances. I had mixed success in terms of immediate satisfaction–I didn’t have a lot of fun reading either of the novels I finished this week, but both were thoughtful books that led to thought-provoking experiences.

I continued trying harder this week to do better reading, choosing books that I hoped would bring more or different rewards than my recent rather desultory choices of mysteries and romances. I had mixed success in terms of immediate satisfaction–I didn’t have a lot of fun reading either of the novels I finished this week, but both were thoughtful books that led to thought-provoking experiences. This is something I would never say in a lecture or a presentation or, God forbid, a paper, but, at a certain point, science fails. Questions become guesses become philosophical ideas about how something should probably, maybe, be. I grew up around people who were distrustful of science, who thought of it as a cunning trick to rob them of their faith, and I have been educated around scientists and laypeople alike who talk about religion as though it were a comfort blanket for the dumb and the weak, a way to extol the virtues of a God more improbable than our own human existence. But this tension, this idea that one must necessarily choose between science and religion, is false. I used to see the world through a God lens, and when that lens clouded, I turned to science. Both became, for me, valuable ways of seeing, but ultimately both have failed to fully satisfy in their aim: to make clear, to make meaning.

This is something I would never say in a lecture or a presentation or, God forbid, a paper, but, at a certain point, science fails. Questions become guesses become philosophical ideas about how something should probably, maybe, be. I grew up around people who were distrustful of science, who thought of it as a cunning trick to rob them of their faith, and I have been educated around scientists and laypeople alike who talk about religion as though it were a comfort blanket for the dumb and the weak, a way to extol the virtues of a God more improbable than our own human existence. But this tension, this idea that one must necessarily choose between science and religion, is false. I used to see the world through a God lens, and when that lens clouded, I turned to science. Both became, for me, valuable ways of seeing, but ultimately both have failed to fully satisfy in their aim: to make clear, to make meaning. The other novel I read this week was Sally Rooney’s Normal People, after finishing the extraordinarily intimate and touching series. I have thought a lot about how watching the adaptation first (something I rarely do) affected my reading of the novel. The most important thing is that it inspired me to read the novel at all: after giving up part way through

The other novel I read this week was Sally Rooney’s Normal People, after finishing the extraordinarily intimate and touching series. I have thought a lot about how watching the adaptation first (something I rarely do) affected my reading of the novel. The most important thing is that it inspired me to read the novel at all: after giving up part way through

Maybe it had something to do with my footwear, but this time it was fireworks, what A. S. Byatt calls “the kick galvanic.” It reminded me that all of art rests in the gap between that which is aesthetically pleasing and that which truly captivates you. And that the tiniest thing can make the difference.

Maybe it had something to do with my footwear, but this time it was fireworks, what A. S. Byatt calls “the kick galvanic.” It reminded me that all of art rests in the gap between that which is aesthetically pleasing and that which truly captivates you. And that the tiniest thing can make the difference. What I didn’t like: Optic Nerve felt really miscellaneous. Its unifying force is Gainza herself, or the narrating version of her, I suppose, but I often found myself puzzled over what else bound together the specific elements she included in each chapter. Sometimes I could see it, or sense it (the chapter about her brother and El Greco, for instance, which turned on ideas about religion, and – I think – on tensions between ascetism and sensuality), but most of the time it seemed random. Was I not reading or thinking hard enough, or was that fragmentation deliberate? Maybe the idea was precisely to scatter our focus, or to reflect the ways our lives are not in fact neatly organized around common themes–or to match her commentary on art, which emphasizes that we should, or always do, feel first and think later. I would have liked a bit of guidance about this from the book itself.

What I didn’t like: Optic Nerve felt really miscellaneous. Its unifying force is Gainza herself, or the narrating version of her, I suppose, but I often found myself puzzled over what else bound together the specific elements she included in each chapter. Sometimes I could see it, or sense it (the chapter about her brother and El Greco, for instance, which turned on ideas about religion, and – I think – on tensions between ascetism and sensuality), but most of the time it seemed random. Was I not reading or thinking hard enough, or was that fragmentation deliberate? Maybe the idea was precisely to scatter our focus, or to reflect the ways our lives are not in fact neatly organized around common themes–or to match her commentary on art, which emphasizes that we should, or always do, feel first and think later. I would have liked a bit of guidance about this from the book itself.

It’s not that I haven’t been reading. In fact, in the last couple of weeks I reread all three novels in Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy, which is, cumulatively, over 900 pages. This is because I’m going to be writing up something about them for the TLS to mark the nice new reissues by Windmill Books. What exactly I’m going to say is something I’m still working out: the problem is not too few ideas but too many, given what strange and fascinating and provoking books these are. But because I have a formal writing project to do about them, I won’t be adding anything about them here. (I

It’s not that I haven’t been reading. In fact, in the last couple of weeks I reread all three novels in Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy, which is, cumulatively, over 900 pages. This is because I’m going to be writing up something about them for the TLS to mark the nice new reissues by Windmill Books. What exactly I’m going to say is something I’m still working out: the problem is not too few ideas but too many, given what strange and fascinating and provoking books these are. But because I have a formal writing project to do about them, I won’t be adding anything about them here. (I  soon: the tl;dr version (though it’s actually quite a short review anyway!) is that they are good and have real historical and moral depth behind the genre-fiction surface, especially through the way their stories reach back to Hungary’s fascist and Soviet-dominated past. My mother kindly just shipped me her copy of Porter’s memoir The Storyteller, apparently out of print now, which I am looking forward to reading.

soon: the tl;dr version (though it’s actually quite a short review anyway!) is that they are good and have real historical and moral depth behind the genre-fiction surface, especially through the way their stories reach back to Hungary’s fascist and Soviet-dominated past. My mother kindly just shipped me her copy of Porter’s memoir The Storyteller, apparently out of print now, which I am looking forward to reading. I’ve done some other reading “just” for myself and it’s really here that I’ve felt that things are not going so smoothly. The books have been fine. Well, two of them have been fine: Jo Baker’s The Body Lies and Kate Clayborn’s Love At First. Baker’s is the next one we’ll be discussing in my book club: because we are all tired, stressed, and distracted, people wanted something plotty, and I took on the job of rounding up some crime fiction options that looked like they would also be “literary” enough for us to have something to talk about. I think we chose reasonably well with The Body Lies: it purports to be a novel about both violence against women and about how that violence is treated in so much crime fiction, meaning it has a metafictional aspect that adds interest beyond the novel’s own story. I finished it quickly, because I found it quite engrossing, so that’s a good sign in a way–but I also finished it unconvinced that it had avoided the trap of reproducing the things it aims to critique. I read it too soon, as we won’t be meeting up for a while, so I’ll have to reread at least part of it before our discussion to refresh my grasp of the particulars: I’ll come to that rereading with this question top of mind.

I’ve done some other reading “just” for myself and it’s really here that I’ve felt that things are not going so smoothly. The books have been fine. Well, two of them have been fine: Jo Baker’s The Body Lies and Kate Clayborn’s Love At First. Baker’s is the next one we’ll be discussing in my book club: because we are all tired, stressed, and distracted, people wanted something plotty, and I took on the job of rounding up some crime fiction options that looked like they would also be “literary” enough for us to have something to talk about. I think we chose reasonably well with The Body Lies: it purports to be a novel about both violence against women and about how that violence is treated in so much crime fiction, meaning it has a metafictional aspect that adds interest beyond the novel’s own story. I finished it quickly, because I found it quite engrossing, so that’s a good sign in a way–but I also finished it unconvinced that it had avoided the trap of reproducing the things it aims to critique. I read it too soon, as we won’t be meeting up for a while, so I’ll have to reread at least part of it before our discussion to refresh my grasp of the particulars: I’ll come to that rereading with this question top of mind. I was really excited for the release of Love At First because I am a big fan of Clayborn’s previous novels: they are in the relatively small cluster of romance novels that I have appreciated more the more often I reread them (which in this case has been quite frequently), because she packs a lot into them. That complexity, which can make them seem a bit cluttered at first, turns out (for me at least) to give them more layers and more interest than I often find in recent examples of the genre, which are either too thin and formulaic to sustain my interest or try too obviously to check off too many boxes, making them read like they were designed by focus groups, rather than emerging in any way organically. I really enjoy the intense specificity of her characters and their lives, including their work, which she pays a lot of attention to (yay, neepery). I feel a bit deflated by Love At First, because it seemed – while both very sweet and very competently written and structured – a lot less interesting and a lot less intense than the others. For the first time reading Clayborn, I felt I was reading something almost generic: the story goes through the motions rather than jumping off the page. I’ll reread it eventually: maybe I will find more in it then. I did like it! But I had hoped to really love it, and I didn’t–at least not at first. 🙂

I was really excited for the release of Love At First because I am a big fan of Clayborn’s previous novels: they are in the relatively small cluster of romance novels that I have appreciated more the more often I reread them (which in this case has been quite frequently), because she packs a lot into them. That complexity, which can make them seem a bit cluttered at first, turns out (for me at least) to give them more layers and more interest than I often find in recent examples of the genre, which are either too thin and formulaic to sustain my interest or try too obviously to check off too many boxes, making them read like they were designed by focus groups, rather than emerging in any way organically. I really enjoy the intense specificity of her characters and their lives, including their work, which she pays a lot of attention to (yay, neepery). I feel a bit deflated by Love At First, because it seemed – while both very sweet and very competently written and structured – a lot less interesting and a lot less intense than the others. For the first time reading Clayborn, I felt I was reading something almost generic: the story goes through the motions rather than jumping off the page. I’ll reread it eventually: maybe I will find more in it then. I did like it! But I had hoped to really love it, and I didn’t–at least not at first. 🙂 And speaking of books I don’t love, I have stalled half way through Kate Weinberg’s The Truants. It showed up on my radar around the same time I was looking into The Body Lies and they seemed so well paired that I ordered them both at the same time. Now I wonder what got into me: I started, hated, and quickly abandoned Donna Tartt’s The Secret History and everything about The Truants (including many of the blurbs!) signals that it is in the same vein. There’s nothing wrong with it qua book; it seems deft and clever and (like The Body Lies, but in a different way) it is also aiming at something metafictional through its engagement with Agatha Christie and ideas about how crime fiction works. But I can’t stand academic stories that turn on cults of personality around professors, which are creepy and and antithetical to everything I believe about teaching, not to mention about student-teacher relationships (hello, Dead Poets Society, which once upon a time I found enthralling but now consider kind of appalling). Also, while I try not to hold academic settings up to reductive standards of realism — and I’m also aware that I don’t understand the British system being portrayed very well, so I can’t actually be sure if I’m right when my reaction is “but this isn’t what we do!” — it gets distracting when the scenarios seem too far off. I have not so far managed to get genuinely interested in any of the characters, which means I keep not picking the book up to read further, which in turn means I’m also not picking up anything else because I feel as if I should finish it first. That’s a foolish “should,” I know, though I am by habit and on principle someone who does mostly try to finish the books I start, in case they get better or I figure out how to read them, both things that have happened often enough to make me hesitant to toss things aside. I’m not going to toss this one aside, or at any rate I’m not going to put it in my malingering “donate” stack (how I wish the book sale was once again able to accept donations, as this stack is getting kind of large!). Instead, I’m going to put it back on my Mysteries shelf and try it again another time.

And speaking of books I don’t love, I have stalled half way through Kate Weinberg’s The Truants. It showed up on my radar around the same time I was looking into The Body Lies and they seemed so well paired that I ordered them both at the same time. Now I wonder what got into me: I started, hated, and quickly abandoned Donna Tartt’s The Secret History and everything about The Truants (including many of the blurbs!) signals that it is in the same vein. There’s nothing wrong with it qua book; it seems deft and clever and (like The Body Lies, but in a different way) it is also aiming at something metafictional through its engagement with Agatha Christie and ideas about how crime fiction works. But I can’t stand academic stories that turn on cults of personality around professors, which are creepy and and antithetical to everything I believe about teaching, not to mention about student-teacher relationships (hello, Dead Poets Society, which once upon a time I found enthralling but now consider kind of appalling). Also, while I try not to hold academic settings up to reductive standards of realism — and I’m also aware that I don’t understand the British system being portrayed very well, so I can’t actually be sure if I’m right when my reaction is “but this isn’t what we do!” — it gets distracting when the scenarios seem too far off. I have not so far managed to get genuinely interested in any of the characters, which means I keep not picking the book up to read further, which in turn means I’m also not picking up anything else because I feel as if I should finish it first. That’s a foolish “should,” I know, though I am by habit and on principle someone who does mostly try to finish the books I start, in case they get better or I figure out how to read them, both things that have happened often enough to make me hesitant to toss things aside. I’m not going to toss this one aside, or at any rate I’m not going to put it in my malingering “donate” stack (how I wish the book sale was once again able to accept donations, as this stack is getting kind of large!). Instead, I’m going to put it back on my Mysteries shelf and try it again another time. I think I need to read something richer and more challenging to turn things around — and to do that I need to stop making excuses about distractions or poor concentration. Reading, including reading well, is a decision we can make, I honestly think, and it’s not just that I feel disappointed in myself when I’m not doing it; it’s also that my life overall feels worse without it. One of my favorite quotations is from Carol Shields’ wonderful novel Unless: “This is why I read novels: so I can escape my own unrelenting monologue.” My current unrelenting monologue (like most people’s these days, I expect) is not a particularly sustaining one: I need reading to give me other stories to think about. I need blogging for the same reason, I find: it is still the only writing I do that feels genuinely my own. This is not by way of making some kind of bold resolution about either reading or blogging, but it actually helps just putting into words why I hope I will be doing more of both.

I think I need to read something richer and more challenging to turn things around — and to do that I need to stop making excuses about distractions or poor concentration. Reading, including reading well, is a decision we can make, I honestly think, and it’s not just that I feel disappointed in myself when I’m not doing it; it’s also that my life overall feels worse without it. One of my favorite quotations is from Carol Shields’ wonderful novel Unless: “This is why I read novels: so I can escape my own unrelenting monologue.” My current unrelenting monologue (like most people’s these days, I expect) is not a particularly sustaining one: I need reading to give me other stories to think about. I need blogging for the same reason, I find: it is still the only writing I do that feels genuinely my own. This is not by way of making some kind of bold resolution about either reading or blogging, but it actually helps just putting into words why I hope I will be doing more of both.