Content warning: depression and suicide

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937)

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937)

I’ve just finished writing a review of Sina Queyras’s new book Rooms: Women, Writing, Woolf, a book that (among other things) examines the influence Virginia Woolf has had on Queyras as a writer and thinker. Woolf, as Queyras discusses, may actually be uniquely influential:

If you’re a woman who has written in English in the last hundred years, you have come through Woolf and have at least some cursory thoughts on her work—if this year is any indication, you’ve written at least a paragraph about her.

When I write about Woolf myself, I feel the same anxieties Queyras expresses in their book, about taking Woolf as a subject and about adding to what’s already been written about her. It’s hard not to feel both inadequate and superfluous. On the other hand, there are few other writers (for me, there’s really only one other writer) whose work is as rewarding to inhabit and to think about. Most recently, I’ve been working on The Years, which I reread last summer as I began to lay out my plans for my current sabbatical leave.

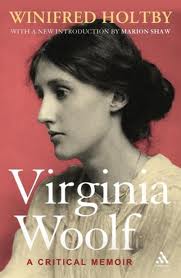

I haven’t written much new about Woolf yet this year (I’ve been focusing on other pieces of my project) but I have thought about her a lot—specifically, I have thought a lot about her suicide. One of my favorite things about Holtby’s Critical Memoir of Woolf is that Holtby died before Woolf did and so no shadow darkens her celebration of Woolf’s capacity for joy. It’s a shame (and I know others, more expert on Woolf than I, who feel this even more strongly) that the popular image of Woolf is so dreary. But she did suffer greatly from depression, and she did ultimately choose not to go on suffering. It’s tragic, of course, but in a way I think the saddest part is not that she died but that she did not wish to go on living, a small distinction, perhaps, but to me a meaningful one. I sometimes feel this about Owen’s death as well: that it’s his life I am mourning—his difficult life, the life he ultimately did not want to live any more—as much as his death. There’s a passage in Meg Mason’s Sorrow and Bliss that captures what I imagine he might have felt:

I haven’t written much new about Woolf yet this year (I’ve been focusing on other pieces of my project) but I have thought about her a lot—specifically, I have thought a lot about her suicide. One of my favorite things about Holtby’s Critical Memoir of Woolf is that Holtby died before Woolf did and so no shadow darkens her celebration of Woolf’s capacity for joy. It’s a shame (and I know others, more expert on Woolf than I, who feel this even more strongly) that the popular image of Woolf is so dreary. But she did suffer greatly from depression, and she did ultimately choose not to go on suffering. It’s tragic, of course, but in a way I think the saddest part is not that she died but that she did not wish to go on living, a small distinction, perhaps, but to me a meaningful one. I sometimes feel this about Owen’s death as well: that it’s his life I am mourning—his difficult life, the life he ultimately did not want to live any more—as much as his death. There’s a passage in Meg Mason’s Sorrow and Bliss that captures what I imagine he might have felt:

Normal people say, I can’t imagine feeling so bad I’d genuinely want to die. I do not try and explain that it isn’t that you want to die. It is that you know you are not supposed to be alive, feeling a tiredness that powders your bones, a tiredness with so much fear. The unnatural fact of living is something you must eventually fix.

How I wish I could have fixed it for him instead, some other way.

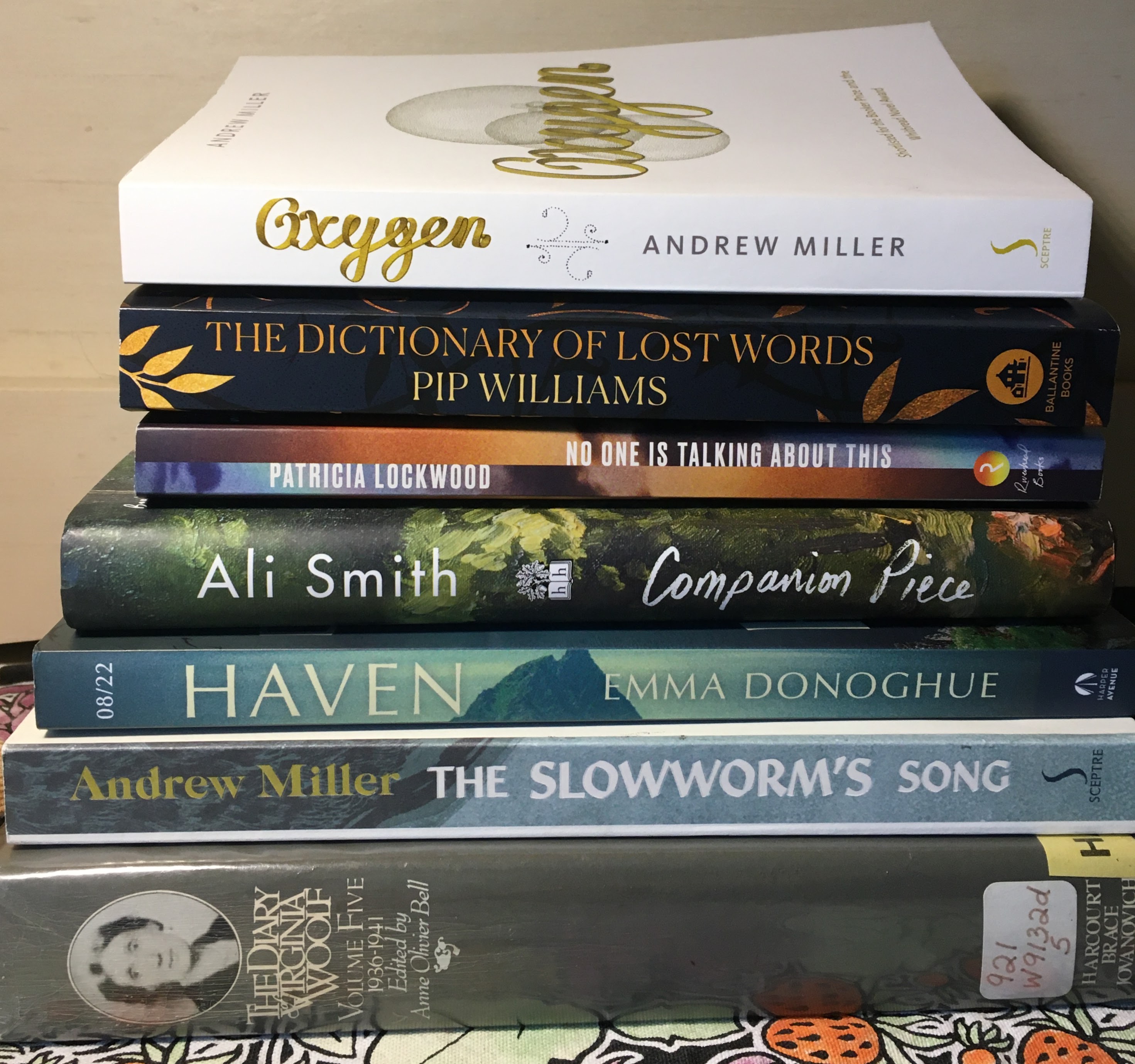

With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

Woolf experienced a lot of painful losses in her life, including her mother and father and her brother Thoby. Julian’s death (in Spain, where he had gone, over his mother’s and aunt’s objections, to drive an ambulance) was another terrible blow. Woolf doesn’t write about it at length, but her grief comes up often over the following months in terms that are now all-too familiar. In the first entry she writes after he dies, she notes how odd it is that “I can hardly bring myself, with all my verbosity . . . to say anything about Julian’s death.” There’s a sense of helplessness, as all she can do is be there for his bereft mother:

Then we came down here [to Monk’s House] last Thursday; & the pressure being removed, one lived; but without much of a future. Thats one of the specific qualities of this death—how it brings close the immense vacancy, & our short little run into inanity.

More than once she resolves to let this renewed consciousness of the brevity of life inspire her to make the most of it: “I will not yield an inch, or a fraction of an inch to nothingness, so long as something remains.” “But how it curtails the future,” she adds, “… a curiously physical sense; as if one had been living in another body, which is removed, & all that living is ended.”

“We don’t talk so freely of Julian,” Woolf remarks a few days later; “We want to make things go on.” After another few days, she writes that Vanessa “looks an old woman”: “How can she ever right herself though?” Woolf herself struggles to focus on her writing projects. “I do not let myself think,” she says; “That is the fact. I cannot face much of the meaning.” “Nessa is alone today,” she notes on August 6; “A very hot day—I add, to escape from the thought of her.” But the thoughts return:

“We don’t talk so freely of Julian,” Woolf remarks a few days later; “We want to make things go on.” After another few days, she writes that Vanessa “looks an old woman”: “How can she ever right herself though?” Woolf herself struggles to focus on her writing projects. “I do not let myself think,” she says; “That is the fact. I cannot face much of the meaning.” “Nessa is alone today,” she notes on August 6; “A very hot day—I add, to escape from the thought of her.” But the thoughts return:

We have the materials for happiness, but no happiness . . . It is an unnatural death, his. I cant make it fit in anywhere. Perhaps because he was killed, violently. I can do nothing with the experience yet. It seems still emptiness: the sight of Nessa bleeding: how we watch: nothing to be done. But whats odd is I cant notice or describe. Of course I have forced myself to drive ahead with the book. But the future without Julian is cut off. lopped: deformed.

“How much do I mind death?” she asks herself in December, concluding that “there is a sense in which the end could be accepted calmly”:

It’s Julian’s death that makes one skeptical of life I suppose. Not that I ever think of him as dead, which is queer. Rather as if he were jerked abruptly out of sight, without rhyme or reason: so violent & absurd that one cant fit his death into any scheme. But here we are . . .

Julian did not choose his death (although presumably he accepted the risk of it, when he chose to go to Spain). That’s a big difference between his “end” (which causes Woolf so much grief) and hers. I have always respected Woolf’s choice (and also Carolyn Heilbrun’s, though her circumstances were very different). I try to respect Owen’s too, to understand it as an expression—the ultimate expression—of his autonomy, his right to decide he had suffered enough. I cannot accept it calmly, though; I feel like Vanessa, “bleeding.” “Here there was no relief,” Woolf says in the immediate aftermath of Julian’s death, watching her sister suffer; “Then I thought the death of a child is childbirth again.”

No, it’s not an elegy, I thought. No parent should write a child’s elegy.

July 2019

July 2019 Since I

Since I

Anyway, this is a pretty roundabout way to get to the point of this post, which is to update the record of my recent reading, if only to shore up my recollections of this period of my life. There’s no way I can write “proper” posts about each of these recently read titles, but I don’t want to forget that I read them, and I also (as part of my larger effort to “reengage with the world”) want to push myself past the sad inertia that at this point is mostly to blame for my losing the habit of writing up my ‘novel readings.’ I remind myself, not for the first time, of my conviction that if something was worth doing before a catastrophe,

Anyway, this is a pretty roundabout way to get to the point of this post, which is to update the record of my recent reading, if only to shore up my recollections of this period of my life. There’s no way I can write “proper” posts about each of these recently read titles, but I don’t want to forget that I read them, and I also (as part of my larger effort to “reengage with the world”) want to push myself past the sad inertia that at this point is mostly to blame for my losing the habit of writing up my ‘novel readings.’ I remind myself, not for the first time, of my conviction that if something was worth doing before a catastrophe,

I have stumbled more in the last couple of weeks, starting and then quitting a lot of titles including Sarah Hall’s Burntcoat and Rachel Cusk’s Second Place, but I did read Monica Ali’s Love Marriage with interest that (with a bit of persistence) grew into appreciation. One book I began with enthusiasm but ultimately decided not to finish was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, which I have read before, long ago (pre-blogging, that’s how long ago!). It was just too religious for me this time: I just don’t see the world as John Ames does, and while as a well-trained and very experienced novel reader I totally understand and agree that I don’t have to in order to engage with his story, this time (with apologies to the people of faith among you) it just felt too much like having to take very seriously someone who believes in

I have stumbled more in the last couple of weeks, starting and then quitting a lot of titles including Sarah Hall’s Burntcoat and Rachel Cusk’s Second Place, but I did read Monica Ali’s Love Marriage with interest that (with a bit of persistence) grew into appreciation. One book I began with enthusiasm but ultimately decided not to finish was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, which I have read before, long ago (pre-blogging, that’s how long ago!). It was just too religious for me this time: I just don’t see the world as John Ames does, and while as a well-trained and very experienced novel reader I totally understand and agree that I don’t have to in order to engage with his story, this time (with apologies to the people of faith among you) it just felt too much like having to take very seriously someone who believes in

The mind is not only its own place, as Milton’s Satan observes, but it can also be a pretty strange place, or mine can anyway, especially these days. Today, for example, it has been six months (six months!) since Owen’s death, and what keeps running through my mind is a mangled version of lines from “The Charge of the Light Brigade”: “half a year, half a year, half a year onward, into the valley of death …” and then nothing comes next, it just starts over, because not only (of course) are these not the poem’s actual words but I don’t know what words of my own should follow to finish the thought.

The mind is not only its own place, as Milton’s Satan observes, but it can also be a pretty strange place, or mine can anyway, especially these days. Today, for example, it has been six months (six months!) since Owen’s death, and what keeps running through my mind is a mangled version of lines from “The Charge of the Light Brigade”: “half a year, half a year, half a year onward, into the valley of death …” and then nothing comes next, it just starts over, because not only (of course) are these not the poem’s actual words but I don’t know what words of my own should follow to finish the thought.

It’s hard to imagine a poem that is less apt, for the occasion or for my feelings about it. (I hate this poem, actually, though I love so much of Tennyson’s poetry.*) I can’t think of any reason for this mental hiccup besides the generally cluttered condition of my mind thanks to two years of COVID isolation and now six months (six months!) of grieving. Six months is half a year—half a year! I have to keep repeating it to make myself believe it, and it’s probably just the repetition and rhythm of that phrase that trips my tired brain over into Tennyson’s too-familiar verse.

Half a year. That stretch of time seemed unfathomably long to me in the first

It’s hard to imagine a poem that is less apt, for the occasion or for my feelings about it. (I hate this poem, actually, though I love so much of Tennyson’s poetry.*) I can’t think of any reason for this mental hiccup besides the generally cluttered condition of my mind thanks to two years of COVID isolation and now six months (six months!) of grieving. Six months is half a year—half a year! I have to keep repeating it to make myself believe it, and it’s probably just the repetition and rhythm of that phrase that trips my tired brain over into Tennyson’s too-familiar verse.

Half a year. That stretch of time seemed unfathomably long to me in the first  How should the thought finish? As I walk through the valley of the shadow of Owen’s death, I have no sure path or comfort. All I know, or hope I know, is that at some point, in some way, I will emerge from it and he will not. Six months ago today, devastated beyond any words of my own, I copied stanzas from Tennyson’s In Memoriam into my journal. It remains the best poem I know about grief, though as it turns towards a resolution not available to me, maybe it’s more accurate to say that it contains the best poetry I know about grief. (For that, I can forgive him the jingoistic tedium of “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”) This has always been my favorite section—it is so powerful in its stark simplicity:

How should the thought finish? As I walk through the valley of the shadow of Owen’s death, I have no sure path or comfort. All I know, or hope I know, is that at some point, in some way, I will emerge from it and he will not. Six months ago today, devastated beyond any words of my own, I copied stanzas from Tennyson’s In Memoriam into my journal. It remains the best poem I know about grief, though as it turns towards a resolution not available to me, maybe it’s more accurate to say that it contains the best poetry I know about grief. (For that, I can forgive him the jingoistic tedium of “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”) This has always been my favorite section—it is so powerful in its stark simplicity:

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937)

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937) I haven’t written much new about Woolf yet this year (I’ve been focusing on other pieces of my project) but I have thought about her a lot—specifically, I have thought a lot about her suicide. One of my favorite things about Holtby’s Critical Memoir of Woolf is that Holtby died before Woolf did and so no shadow darkens her celebration of

I haven’t written much new about Woolf yet this year (I’ve been focusing on other pieces of my project) but I have thought about her a lot—specifically, I have thought a lot about her suicide. One of my favorite things about Holtby’s Critical Memoir of Woolf is that Holtby died before Woolf did and so no shadow darkens her celebration of  With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

The aspect of the novel that I found the most thought-provoking is that the act that precipitates Stephen’s subsequent descent into alcoholism and despair is (relatively speaking) quite a small-scale one. There’s a lot of build-up to it, a lot of manipulative anticipation created. In the lead-up to the revelation, we hear about a range of horrifying atrocities—booby-traps and bombs; gangs kidnapping, torturing, and murdering people; cold-blooded shootings of people pulled from their cars in front of their families—so it’s almost an anti-climax when we find out that what Stephen did (“all” Stephen did) was shoot an unarmed teenager. It happens during a house search, a routine but also very tense operation: everything, we have learned by this point, is unpredictable in Belfast, and being on edge is a way of life for the soldiers on patrol. Stephen is posted in the alley; when the boy comes out of the back door, all Stephen registers is that “his hands were not quite empty.” Afterwards, Stephen is encouraged to dwell on the perceived threat: “if I’d believed my life was in danger then I’d had every right to do as I did.” He does as he’s told, and in the end there are no formal consequences beyond his being relocated out of Ireland.

The aspect of the novel that I found the most thought-provoking is that the act that precipitates Stephen’s subsequent descent into alcoholism and despair is (relatively speaking) quite a small-scale one. There’s a lot of build-up to it, a lot of manipulative anticipation created. In the lead-up to the revelation, we hear about a range of horrifying atrocities—booby-traps and bombs; gangs kidnapping, torturing, and murdering people; cold-blooded shootings of people pulled from their cars in front of their families—so it’s almost an anti-climax when we find out that what Stephen did (“all” Stephen did) was shoot an unarmed teenager. It happens during a house search, a routine but also very tense operation: everything, we have learned by this point, is unpredictable in Belfast, and being on edge is a way of life for the soldiers on patrol. Stephen is posted in the alley; when the boy comes out of the back door, all Stephen registers is that “his hands were not quite empty.” Afterwards, Stephen is encouraged to dwell on the perceived threat: “if I’d believed my life was in danger then I’d had every right to do as I did.” He does as he’s told, and in the end there are no formal consequences beyond his being relocated out of Ireland.

The past few weeks, though still often sad and difficult, have been a bit better for reading. I’m not sure if it’s me or the books—probably a bit of both.

The past few weeks, though still often sad and difficult, have been a bit better for reading. I’m not sure if it’s me or the books—probably a bit of both. I didn’t much like Andrew Sean Greer’s Less. I persisted to the end, but it never engaged me deeply at all. My least favorite quality in a book is archness, and that seemed to me Less‘s primary mood. It will shock some of my Twitter friends when I say that I also didn’t much like Laurie Colwin’s Happy All The Time: it isn’t arch, exactly, but it is crisp and clever and detached to the point that it felt thin, even superficial, and thus unsatisfying. I was interested in the premise of Kate Grenville’s A House Made of Leaves and there are good things about it, but overall the execution felt dry and the messages (about history and gender and colonialism) perfunctory, delivered rather than dramatized.

I didn’t much like Andrew Sean Greer’s Less. I persisted to the end, but it never engaged me deeply at all. My least favorite quality in a book is archness, and that seemed to me Less‘s primary mood. It will shock some of my Twitter friends when I say that I also didn’t much like Laurie Colwin’s Happy All The Time: it isn’t arch, exactly, but it is crisp and clever and detached to the point that it felt thin, even superficial, and thus unsatisfying. I was interested in the premise of Kate Grenville’s A House Made of Leaves and there are good things about it, but overall the execution felt dry and the messages (about history and gender and colonialism) perfunctory, delivered rather than dramatized. I have some promising options in my TBR pile to choose from next, including Nicola Griffith’s Spear (a sequel to

I have some promising options in my TBR pile to choose from next, including Nicola Griffith’s Spear (a sequel to  I’ve assigned Margaret Oliphant’s Autobiography many times over the years in the graduate seminar I’ve offered on Victorian women writers. I read it first myself in a similar seminar offered by Dorothy Mermin at Cornell: I realized later that this was while she was working on her excellent book

I’ve assigned Margaret Oliphant’s Autobiography many times over the years in the graduate seminar I’ve offered on Victorian women writers. I read it first myself in a similar seminar offered by Dorothy Mermin at Cornell: I realized later that this was while she was working on her excellent book

Twenty-one years pass between these painful sections and the next section of the Autobiography, and in that gap is, as she notes, “a little lifetime.” “I have just been rereading it all with tears,” she says, “sorry, very sorry for that poor little soul who has lived through so much since.” Writing those words in 1885, she had no idea how much more sorrow lay ahead. First came the death of her son Cyril in 1890 (“I have been permitted to do everything for him, to wind up his young life, to accept the thousand and thousand disappointments and thoughts of what might have been”), and then in 1894, the death of her son Cecco (“The younger after the elder and on this earth I have no son—I have no child. I am a mother childless”). “What have I left now?” she laments. “My work is over, my house is desolate. I am empty of all things.” In her despair (“It is not in me to take a dose and end it. Oh I wish it were”), her vast literary output brings her no comfort: “nobody thinks that the few books I will leave behind me count for anything.”

Twenty-one years pass between these painful sections and the next section of the Autobiography, and in that gap is, as she notes, “a little lifetime.” “I have just been rereading it all with tears,” she says, “sorry, very sorry for that poor little soul who has lived through so much since.” Writing those words in 1885, she had no idea how much more sorrow lay ahead. First came the death of her son Cyril in 1890 (“I have been permitted to do everything for him, to wind up his young life, to accept the thousand and thousand disappointments and thoughts of what might have been”), and then in 1894, the death of her son Cecco (“The younger after the elder and on this earth I have no son—I have no child. I am a mother childless”). “What have I left now?” she laments. “My work is over, my house is desolate. I am empty of all things.” In her despair (“It is not in me to take a dose and end it. Oh I wish it were”), her vast literary output brings her no comfort: “nobody thinks that the few books I will leave behind me count for anything.” She kept writing, though, not just the Autobiography—which she reconceived somewhat, pragmatically, once it was no longer intended for her children, as something lighter and more anecdotal—but also more fiction, including her excellent ghost story “The Library Window,” recently reprinted by Broadview. It’s not hard to understand the appeal of ghost stories to a mother whose beloved children would have been there but not there every waking minute. I know what that’s like.

She kept writing, though, not just the Autobiography—which she reconceived somewhat, pragmatically, once it was no longer intended for her children, as something lighter and more anecdotal—but also more fiction, including her excellent ghost story “The Library Window,” recently reprinted by Broadview. It’s not hard to understand the appeal of ghost stories to a mother whose beloved children would have been there but not there every waking minute. I know what that’s like. I’ve been thinking about how many times people have expressed their love and sympathy for us by saying “there are no words,” and then about how important it has felt to me, since Owen’s death, to try to find some words for what it feels like to lose him and grieve for him. Writing has helped, even though I have also often felt the truth of Tennyson’s lines:

I’ve been thinking about how many times people have expressed their love and sympathy for us by saying “there are no words,” and then about how important it has felt to me, since Owen’s death, to try to find some words for what it feels like to lose him and grieve for him. Writing has helped, even though I have also often felt the truth of Tennyson’s lines: