Look, I don’t want to pretend everything is fine, in general or in my classes. Last week I was grading take-home midterms for Mystery & Detective Fiction and feeling to my core the truth of what is now a commonplace: AI is pervasive, and not “for better or for worse”—just, unequivocally, for worse. The one consolation I had (and it is, truly, not particularly consoling) is that the results, for the students, are not usually good. This means it doesn’t matter whether I can prove AI use or not: I can just mark the answers on their merits and move on. But it really sucks going through this process and wondering what the point of it even is. I felt demoralized, sad, and frustrated, which is unfortunately how I have often felt about this course this term because attendance has been so poor: on a good day, maybe 60% of the students are present, and there are some who have almost never been to class at all since January. What am I even doing, I have wondered, and how much longer can I keep doing it if it just no longer means to them anything like what it means to me?

Look, I don’t want to pretend everything is fine, in general or in my classes. Last week I was grading take-home midterms for Mystery & Detective Fiction and feeling to my core the truth of what is now a commonplace: AI is pervasive, and not “for better or for worse”—just, unequivocally, for worse. The one consolation I had (and it is, truly, not particularly consoling) is that the results, for the students, are not usually good. This means it doesn’t matter whether I can prove AI use or not: I can just mark the answers on their merits and move on. But it really sucks going through this process and wondering what the point of it even is. I felt demoralized, sad, and frustrated, which is unfortunately how I have often felt about this course this term because attendance has been so poor: on a good day, maybe 60% of the students are present, and there are some who have almost never been to class at all since January. What am I even doing, I have wondered, and how much longer can I keep doing it if it just no longer means to them anything like what it means to me?

BUT.

Here’s the other side of how things have been going in Mystery & Detective Fiction. There is a solid core of students who come every single time (or close enough—it’s perfectly reasonable, of course, to miss a class here and there because you are sick or your bus was late or whatever). I don’t know if they are all reading every page of every book, but enough of them are keeping up that we have pretty good discussions: the ones who speak up seem keen and interested, and they seem to be listening to each other, and they laugh when I try to be funny (which is one way to see if they are paying attention!). We have worked our way through a lot of good, complex, thought-provoking fiction, most recently Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s The Terrorists. (It is a book that seems uncannily relevant to our current moment, with its questions about what happens to citizens when their government is actively indifferent to their needs and politics is the playground of people too corrupt and too wealthy to be held accountable.) Sure, a lot of the midterms I marked had the whiff of ChatGPT (or Copilot, I guess, which is now oh-so-helpfully available via the Microsoft suite the university installs on its computers)—but a lot of them did not, and some of these were really excellent. To answer my own plaintive question, then, what I am doing is showing up, as cheerily as I can, to offer these students the class they deserve. As always, I will also keep puzzling about how to reach the ones who aren’t: AI may be new, but students turn to it for reasons that are not new, reasons I have been trying to find solutions for as long as I have been teaching.

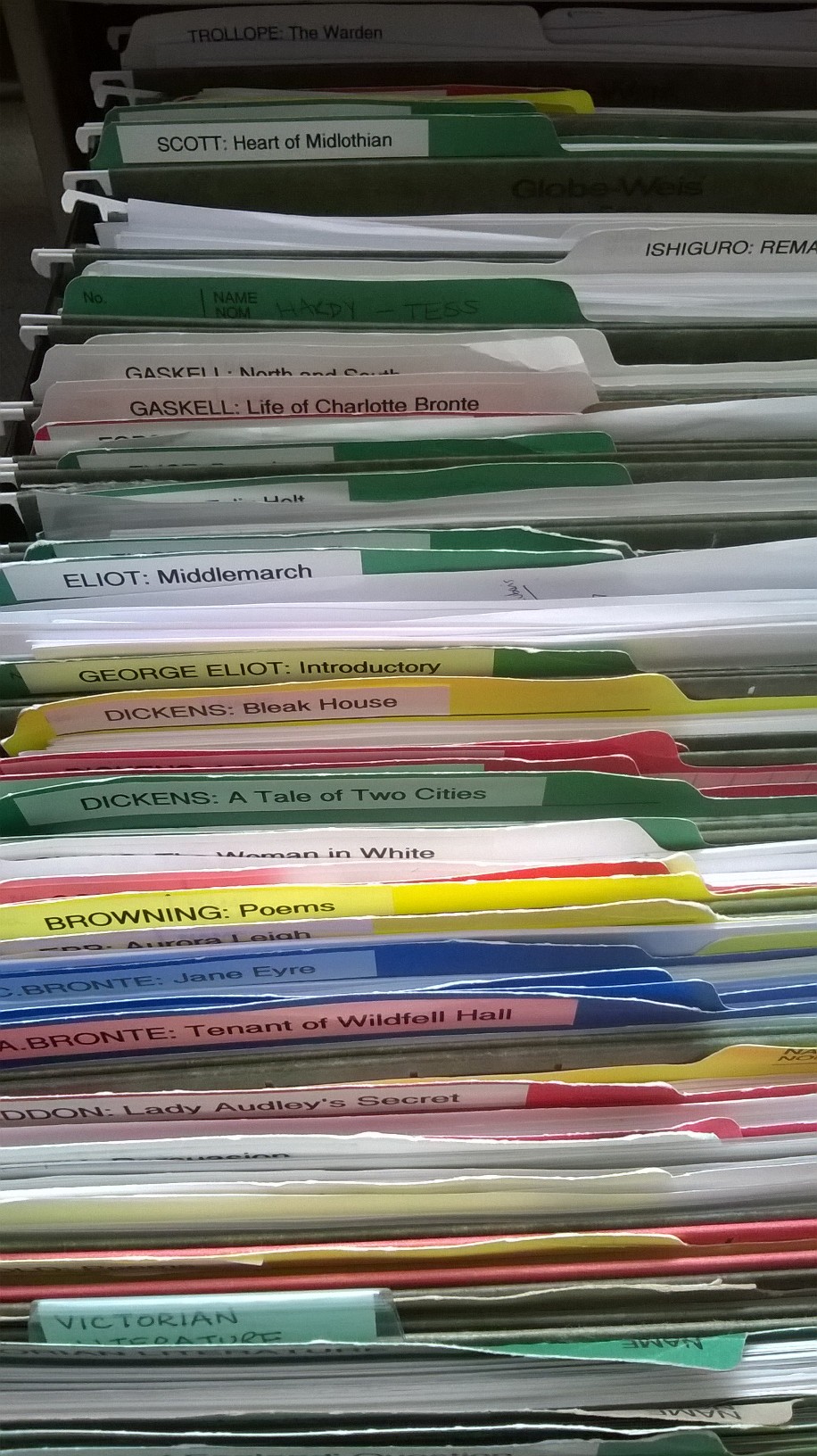

Even to myself this positive spin, if that’s what it is, does not sound completely convincing. Yes, something is different now. I’m just not sure it’s as bad as this gloomy article says it is. Maybe I’m kidding myself. A few years back, one of my best students let slip that a lot of students in my 19thC fiction class were basing their contributions on what they’d read in SparkNotes, not the assigned novels themselves. I wished she hadn’t said that! Was it true? Is it still true? It doesn’t feel true in these classes! I want to believe! But also, even if it is true about some students, it is definitely not true of all students. I just get too much evidence to the contrary, often from conversations with students outside of class, like the one who came to my office hours recently to talk about her term paper ideas but also to ask for recommendations for more Victorian novels to read after she graduates. Guess which novel she’d studied with me had most won her heart: David Copperfield! (It is truly heartwarming how many students who were in the Austen to Dickens class last year have told me they loved David Copperfield. A lot of them signed up for Dickens to Hardy this year and I have never had a group dig in to Bleak House with so much enthusiasm!) Twice this term, students who had already graduated from Dalhousie asked to sit in on my Victorian Women Writers seminar just to hear some of our discussions of Middlemarch. The current students who are actually taking that seminar seem genuinely caught up in the novel—some of them so much so that they will be writing on it. Those who aren’t will be writing on Villette, or on North and South.

These are long, complex, demanding books! So when the author of that essay declares that “our average graduate literally could not read a serious adult novel cover-to-cover and understand what they read,” that students “are impatient to get through whatever burden of reading they have to, and move their eyes over the words just to get it done,” I have to wonder: are my students really so exceptional? I mean, I do think they are lovely and wonderful; I genuinely look forward to every class. It’s true they are English students, and mostly Honours English students at that, with some graduate students as well, so definitely, when it comes to reading, both an elite and a self-selecting group. Still, when we tell stories about higher ed today, shouldn’t we talk about them too?

These are long, complex, demanding books! So when the author of that essay declares that “our average graduate literally could not read a serious adult novel cover-to-cover and understand what they read,” that students “are impatient to get through whatever burden of reading they have to, and move their eyes over the words just to get it done,” I have to wonder: are my students really so exceptional? I mean, I do think they are lovely and wonderful; I genuinely look forward to every class. It’s true they are English students, and mostly Honours English students at that, with some graduate students as well, so definitely, when it comes to reading, both an elite and a self-selecting group. Still, when we tell stories about higher ed today, shouldn’t we talk about them too?

It’s not just about choosing between glass half empty and glass half full perspectives: I think it really matters that we not turn our grimmest anecdata into the dominant narrative. If things are really as bad as all that, after all, what are we all doing, and how much longer should we keep doing it? It is important that alongside our laments about the “stunning level of student disconnection” we acknowledge the students who do care, who choose engagement, who want to read and think and write and don’t want their education to be stripped of its humanity (and the humanities). Here in Nova Scotia our provincial government has proposed a bill that would give them the power to interfere with universities that aren’t doing what they consider a good enough job serving “provincial priorities.” Giving these students the education they want and deserve should be one of those priorities—though I am morally certain that is not the kind of thing our leaders have in mind, even though, as we have explained over and over, studying literature actually is excellent preparation for a whole range of careers, if that’s what you think is the point of an education. (Do you think if I dropped off copies of Hard Times at Province House they would see themselves in Gradgrind and M’Choakumchild and be ashamed?)

Anyway. I am as guilty as the next tired professor of occasionally giving in to cynicism and anger and venting some of it on social media. Many of us believe, or at least hope, that AI will go the way of MOOCs (remember when they were going to revolutionize education?). In the meantime it is definitely making things harder for us, and (despite the edtech industry’s promises) no better for the students, unless “ubiquitous” and “seems easier than doing the work myself” is all that counts. The antidote to despair is not AI detectors or in-class tests, though: it’s the students themselves. Just as I thought we should stand up to the Srigleys of the world when they declared our classrooms “contentless” and said we were leaving our students’ “real intellectual and and moral needs unmet,” so too I think we should counter the “it’s all over” doomsayers with some positivity. I am a Victorianist, after all! Optimism comes with the territory.

I’ve been ordering next year’s books — not because I’m that ahead of the game in general but because early ordering enables the bookstore to retain leftover copies from this year’s stock and students to get cash back at the end of term if they have books we’re using again. I’m teaching a couple of the same classes again in 2023-24 (my first-year writing class and Mystery & Detective Fiction) and so it isn’t too hard to get those orders sorted out. While I was at it, I thought I’d also make my mind up about which novels I’d assign for the Austen to Dickens course (this year I’m doing Dickens to Hardy — once upon a time I taught them both every year, but now I do them in alternate years) . . . and this has had me thinking about how my reading lists have changed over the past twenty years.

I’ve been ordering next year’s books — not because I’m that ahead of the game in general but because early ordering enables the bookstore to retain leftover copies from this year’s stock and students to get cash back at the end of term if they have books we’re using again. I’m teaching a couple of the same classes again in 2023-24 (my first-year writing class and Mystery & Detective Fiction) and so it isn’t too hard to get those orders sorted out. While I was at it, I thought I’d also make my mind up about which novels I’d assign for the Austen to Dickens course (this year I’m doing Dickens to Hardy — once upon a time I taught them both every year, but now I do them in alternate years) . . . and this has had me thinking about how my reading lists have changed over the past twenty years. When I came back to in-person teaching last term, I was wary about going back to pre-pandemic norms. Things in general didn’t really seem normal, after all. So once again I assigned just four novels. OK, one of them was Middlemarch! (But again, I used to assign Middlemarch routinely as one of five or even six.) My impression was that for many of the students, this reduced reading load was a lot — overwhelming, even, for some of them — and so I have ordered just four novels again for next year (although one of them is David Copperfield).

When I came back to in-person teaching last term, I was wary about going back to pre-pandemic norms. Things in general didn’t really seem normal, after all. So once again I assigned just four novels. OK, one of them was Middlemarch! (But again, I used to assign Middlemarch routinely as one of five or even six.) My impression was that for many of the students, this reduced reading load was a lot — overwhelming, even, for some of them — and so I have ordered just four novels again for next year (although one of them is David Copperfield).

I could still add a fifth book to next year’s list if I want to. So far, I’m committed to Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and The Warden. In 2017 I assigned Persuasion, Vanity Fair, Jane Eyre, North and South, and Great Expectations for the same course; in 2013 the list was Persuasion, Waverley, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and North and South (I remember that year distinctly, because it was the year of the

I could still add a fifth book to next year’s list if I want to. So far, I’m committed to Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and The Warden. In 2017 I assigned Persuasion, Vanity Fair, Jane Eyre, North and South, and Great Expectations for the same course; in 2013 the list was Persuasion, Waverley, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and North and South (I remember that year distinctly, because it was the year of the  As if converting my courses to online versions wasn’t challenging enough, I also used specifications grading for the first time this fall, for my first-year class “Literature: How It Works.” This is an experiment I had been thinking a lot about before the pandemic struck: in fact, on March 13, the last day we were all on campus, I actually had a meeting with our Associate Dean to discuss how to make sure doing so wouldn’t conflict with any of the university’s or faculty’s policies. Though I did have some second thoughts after the “pivot” to online teaching, it seemed to me that many features of specifications grading were well suited to Brightspace-based delivery, so I decided to persist with the plan, and I spent a great deal of time and thought over the summer figuring out my version of it.

As if converting my courses to online versions wasn’t challenging enough, I also used specifications grading for the first time this fall, for my first-year class “Literature: How It Works.” This is an experiment I had been thinking a lot about before the pandemic struck: in fact, on March 13, the last day we were all on campus, I actually had a meeting with our Associate Dean to discuss how to make sure doing so wouldn’t conflict with any of the university’s or faculty’s policies. Though I did have some second thoughts after the “pivot” to online teaching, it seemed to me that many features of specifications grading were well suited to Brightspace-based delivery, so I decided to persist with the plan, and I spent a great deal of time and thought over the summer figuring out my version of it. I won’t go into every detail of the plan I finally came up with (though if anyone is really keen to see the extensive documentation, I’d be happy to share it by email). Basically, I made a list of the kinds of work I wanted students to do in service of the course’s multiple objectives: reading journals, discussion posts and replies, writing worksheets, quizzes, and essays. Then I worked out what seemed to me reasonable quantities of each component for bundles I called PASS, CORE, MORE, and MOST. These bundles corresponded to D, C, B, and A grades at the end of term; students’ grades on the final exam determined if they got a + or – added to their letter grade. I also (and in many ways this is the most important part of the whole system!) drew up the specifications for what would count as satisfactory work of each kind: completing a bundle didn’t mean just turning in enough components but turning in enough that met the specifications. Following the lead of others who have used this kind of system, I tried to make the specifications equivalent to something more like a typical B than a bare pass.

I won’t go into every detail of the plan I finally came up with (though if anyone is really keen to see the extensive documentation, I’d be happy to share it by email). Basically, I made a list of the kinds of work I wanted students to do in service of the course’s multiple objectives: reading journals, discussion posts and replies, writing worksheets, quizzes, and essays. Then I worked out what seemed to me reasonable quantities of each component for bundles I called PASS, CORE, MORE, and MOST. These bundles corresponded to D, C, B, and A grades at the end of term; students’ grades on the final exam determined if they got a + or – added to their letter grade. I also (and in many ways this is the most important part of the whole system!) drew up the specifications for what would count as satisfactory work of each kind: completing a bundle didn’t mean just turning in enough components but turning in enough that met the specifications. Following the lead of others who have used this kind of system, I tried to make the specifications equivalent to something more like a typical B than a bare pass. To start with, then, what seemed to go well? First, especially when it came time to assess the students’ longer essays, I really appreciated being freed from assigning them letter grades. Almost every single essay submitted (so, nearly 180 assignments over the term) clearly met the specifications for the assignment, so our focus could be on giving feedback, not (consciously or unconsciously) trying to justify minute gradations in our assessments. I hadn’t realized just how much it weighed on me needing to make artificially precise distinctions between, say, B- and C+ papers, or trying to decide if an unsuccessful attempt at a more ambitious or original argument should really get the same grade as an immaculately polished version of one that mostly reiterated my lectures. Once I’d read through a submission to see if it met the specifications, I could go back and reread with an eye to engaging with it honestly and constructively. This is what I thought I did already, but if you haven’t ever tried grading essays without actually grading them, you too may be surprised at how liberating it feels to let go of that awareness that when you’re done, you have to put a particular pin in it.

To start with, then, what seemed to go well? First, especially when it came time to assess the students’ longer essays, I really appreciated being freed from assigning them letter grades. Almost every single essay submitted (so, nearly 180 assignments over the term) clearly met the specifications for the assignment, so our focus could be on giving feedback, not (consciously or unconsciously) trying to justify minute gradations in our assessments. I hadn’t realized just how much it weighed on me needing to make artificially precise distinctions between, say, B- and C+ papers, or trying to decide if an unsuccessful attempt at a more ambitious or original argument should really get the same grade as an immaculately polished version of one that mostly reiterated my lectures. Once I’d read through a submission to see if it met the specifications, I could go back and reread with an eye to engaging with it honestly and constructively. This is what I thought I did already, but if you haven’t ever tried grading essays without actually grading them, you too may be surprised at how liberating it feels to let go of that awareness that when you’re done, you have to put a particular pin in it. On a related note, something else that I think was good (though it was a bit hard for me to tell without having a chance to talk it over with the class in person) was that the system gave students a fair amount of control over their final grade for the course. Instead of trying to meet some standard that–no matter how carefully you explain and model it–often seems obscure to students, especially in first-year (“what do you want?” is an ordinarily all-too-frequent question about their essay assignments) they could keep a tally of their satisfactory course components and know exactly what else they needed to do to complete a particular bundle and thus earn a particular grade. That didn’t mean it was an automatic process; again, to be rated satisfactory, the work had to meet the specifications I set. I tried to make the specifications concrete, though: they didn’t include any abstract qualitative standards (like “excellence” or “thoughtful”). The core standards were things like “on time,” “on topic,” “within the word limit,” and, most important, to my mind, “shows a good faith effort” to do the task at hand. I suppose that last one is open to interpretation, but I think it sends the right message to students trying to learn how to do something unfamiliar: if they actually try to do it, that counts. When my TA and I debated the occasional submission that had arguably missed the mark in some other way, we used “good faith effort” as the deciding factor for whether they earned the credit: we used it generously, rather than punitively.

On a related note, something else that I think was good (though it was a bit hard for me to tell without having a chance to talk it over with the class in person) was that the system gave students a fair amount of control over their final grade for the course. Instead of trying to meet some standard that–no matter how carefully you explain and model it–often seems obscure to students, especially in first-year (“what do you want?” is an ordinarily all-too-frequent question about their essay assignments) they could keep a tally of their satisfactory course components and know exactly what else they needed to do to complete a particular bundle and thus earn a particular grade. That didn’t mean it was an automatic process; again, to be rated satisfactory, the work had to meet the specifications I set. I tried to make the specifications concrete, though: they didn’t include any abstract qualitative standards (like “excellence” or “thoughtful”). The core standards were things like “on time,” “on topic,” “within the word limit,” and, most important, to my mind, “shows a good faith effort” to do the task at hand. I suppose that last one is open to interpretation, but I think it sends the right message to students trying to learn how to do something unfamiliar: if they actually try to do it, that counts. When my TA and I debated the occasional submission that had arguably missed the mark in some other way, we used “good faith effort” as the deciding factor for whether they earned the credit: we used it generously, rather than punitively. One other way I consider the experiment a success was that it seemed to me that the students’ quantity of work–their consistent effort over time–did ultimately lead to improvements in the quality of their work. The skepticism I faced from some colleagues when I mentioned this plan tended to focus on concerns about rewarding quantity over quality, or about not sufficiently recognizing and rewarding exceptional quality. Over the term I did sometimes worry about this myself: much as I liked being freed from grading individual assignments, I didn’t always like giving the same assessment of ‘satisfactory’ to assignments that ranged from perfunctory or barely passable at one end of the scale to impressively articulate and insightful at the other. You can signal the difference through your feedback, though, and that’s the big shift specifications grading requires. The other key point is that most people really do get better at writing if they practice (and get feedback, and engage with lots of examples of other people’s writing) and so making it a requirement for a good grade that you had to write a lot had the side-effect (or, met the course objective!) of helping a lot of students improve as writers. Between reading journals and discussion posts and replies, there was no way to get an A in this version of the course without writing a few hundred words every week, which is a lot more than students necessarily have to do in my face-to-face versions of intro classes. Especially in their final batch of essays, I think that practice showed.

One other way I consider the experiment a success was that it seemed to me that the students’ quantity of work–their consistent effort over time–did ultimately lead to improvements in the quality of their work. The skepticism I faced from some colleagues when I mentioned this plan tended to focus on concerns about rewarding quantity over quality, or about not sufficiently recognizing and rewarding exceptional quality. Over the term I did sometimes worry about this myself: much as I liked being freed from grading individual assignments, I didn’t always like giving the same assessment of ‘satisfactory’ to assignments that ranged from perfunctory or barely passable at one end of the scale to impressively articulate and insightful at the other. You can signal the difference through your feedback, though, and that’s the big shift specifications grading requires. The other key point is that most people really do get better at writing if they practice (and get feedback, and engage with lots of examples of other people’s writing) and so making it a requirement for a good grade that you had to write a lot had the side-effect (or, met the course objective!) of helping a lot of students improve as writers. Between reading journals and discussion posts and replies, there was no way to get an A in this version of the course without writing a few hundred words every week, which is a lot more than students necessarily have to do in my face-to-face versions of intro classes. Especially in their final batch of essays, I think that practice showed. It hasn’t been all bad, though.

It hasn’t been all bad, though.  So what have I learned? In addition to the technical stuff – Brightspace and Panopto and Collaborate, oh my! – I have learned, as a lot of other people have too, that the best advice and methods for online teaching

So what have I learned? In addition to the technical stuff – Brightspace and Panopto and Collaborate, oh my! – I have learned, as a lot of other people have too, that the best advice and methods for online teaching

Like everyone else in the world (and how odd for that not to be hyperbole, though our timelines have differed) I have spent the past week adjusting to the unprecedented risks and disruptions created by the spread of COVID-19. Friday March 13 began as a more or less ordinary day of classes: the cloud was looming on the horizon, reports were coming in of the first university closures in Canada, and we had been instructed to start making contingency plans in case Dalhousie followed suit. But my schedule that day was normal almost to the end: I had a meeting with our Associate Dean Academic to discuss my interest in trying contract grading in my first-year writing class; I taught the second of four planned classes on Three Guineas in the Brit Lit survey class and of four planned classes on Mary Barton in 19th-Century British Fiction. The only real break from routine was a brisk walk down to Spring Garden Road at lunch time to pick up a couple of items I thought it might be nice to have secured, just in case: Helene Tursten’s An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good for my book club, which I knew had just come in at Bookmark, and a bottle of my favorite Body Shop shower gel (

Like everyone else in the world (and how odd for that not to be hyperbole, though our timelines have differed) I have spent the past week adjusting to the unprecedented risks and disruptions created by the spread of COVID-19. Friday March 13 began as a more or less ordinary day of classes: the cloud was looming on the horizon, reports were coming in of the first university closures in Canada, and we had been instructed to start making contingency plans in case Dalhousie followed suit. But my schedule that day was normal almost to the end: I had a meeting with our Associate Dean Academic to discuss my interest in trying contract grading in my first-year writing class; I taught the second of four planned classes on Three Guineas in the Brit Lit survey class and of four planned classes on Mary Barton in 19th-Century British Fiction. The only real break from routine was a brisk walk down to Spring Garden Road at lunch time to pick up a couple of items I thought it might be nice to have secured, just in case: Helene Tursten’s An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good for my book club, which I knew had just come in at Bookmark, and a bottle of my favorite Body Shop shower gel (

Anyway, it quickly became clear that the right strategy (and, to their credit, the one our administrators have been urging) is not to try to replicate electronically all of our plans for the last few weeks of term, including the final exam period, but to smooth students’ paths to completion as best we can: dropping readings and assignments and giving them options including taking the grade they have earned so far but still also allowing another chance to do better in as painless a way as we can think of. I think the options I came up with for my classes are pretty good, in these respects, but it may be that they don’t go far enough, because this is all turning out to be so much harder than it sounded a week ago–and of course however we might (or might not!) be managing, our students have their own specific circumstances which may make even the most “reasonable” alternatives too much. I have been feeling a lot of regret about the books we won’t get to, especially The Remains of the Day, which I was increasingly excited about as the capstone text for the survey class–what a good book to read right after Three Guineas! As for Three Guineas itself, I was so excited about teaching it for the first time. It’s definitely going back on my syllabus the next time it fits the brief. Sigh.

Anyway, it quickly became clear that the right strategy (and, to their credit, the one our administrators have been urging) is not to try to replicate electronically all of our plans for the last few weeks of term, including the final exam period, but to smooth students’ paths to completion as best we can: dropping readings and assignments and giving them options including taking the grade they have earned so far but still also allowing another chance to do better in as painless a way as we can think of. I think the options I came up with for my classes are pretty good, in these respects, but it may be that they don’t go far enough, because this is all turning out to be so much harder than it sounded a week ago–and of course however we might (or might not!) be managing, our students have their own specific circumstances which may make even the most “reasonable” alternatives too much. I have been feeling a lot of regret about the books we won’t get to, especially The Remains of the Day, which I was increasingly excited about as the capstone text for the survey class–what a good book to read right after Three Guineas! As for Three Guineas itself, I was so excited about teaching it for the first time. It’s definitely going back on my syllabus the next time it fits the brief. Sigh. One of the most emotionally painful parts of all of this has been the abrupt severance of personal relationships, which is what teaching is really all about. I have put course materials together to get us to the end of our current texts, but it is much less rewarding scripting them than it is taking my ideas and questions in to meet them with and seeing what comes of our encounter. Sure, it doesn’t always go swimmingly, but that just means you try again, or try something different. I know there are ways to include more personal and “synchronous” interaction (as we’ve quickly learned to label it!) in online teaching, and of course as someone who spends a lot of time online I already believe that you can cultivate meaningful relationships without meeting face to face. There just isn’t time for that now, though, and also the demands those tools put on everyone to be available and attentive at the same time are all wrong for our immediate circumstances. It isn’t just about finding ways to get through the course material together either: there are students I have been working with for years who it turns out I saw in person for maybe the last time that Friday without even knowing it. I have been thinking about them, and about all of my students, so much since that hectic departure from campus and hoping they know how much I have valued our time together and how much I already miss them!

One of the most emotionally painful parts of all of this has been the abrupt severance of personal relationships, which is what teaching is really all about. I have put course materials together to get us to the end of our current texts, but it is much less rewarding scripting them than it is taking my ideas and questions in to meet them with and seeing what comes of our encounter. Sure, it doesn’t always go swimmingly, but that just means you try again, or try something different. I know there are ways to include more personal and “synchronous” interaction (as we’ve quickly learned to label it!) in online teaching, and of course as someone who spends a lot of time online I already believe that you can cultivate meaningful relationships without meeting face to face. There just isn’t time for that now, though, and also the demands those tools put on everyone to be available and attentive at the same time are all wrong for our immediate circumstances. It isn’t just about finding ways to get through the course material together either: there are students I have been working with for years who it turns out I saw in person for maybe the last time that Friday without even knowing it. I have been thinking about them, and about all of my students, so much since that hectic departure from campus and hoping they know how much I have valued our time together and how much I already miss them! And now, I guess, it’s time to settle in to what people keep euphemistically calling “the new normal.” Here in Halifax we are under strong directions for social distancing; I’ve heard rumors that something more rigorous might be coming, in the hope of really flattening that infamous curve. There are lots of wry jokes and memes about readers or introverts or others whose habits and preferences mean they have been “preparing for this moment our whole lives.” We live a pretty quiet life ourselves, so to some extent this is true of us as well (though not of Maddie, who like many young people is going to be very well served by the various ways she and her friends can stay in touch virtually). It’s pretty different having to stay home, though, and also worrying whenever you go out, even if it’s only for essentials. It’s also not spring yet here–I envy my family in Vancouver the softening weather that makes walks and parks and gardens good options. I am grateful, though, that we are comfortable and together and, so far, healthy. I am also glad I did pick up An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good, because I finished reading it this morning and it is a nice bit of twisted fun…about which more soon, I hope!

And now, I guess, it’s time to settle in to what people keep euphemistically calling “the new normal.” Here in Halifax we are under strong directions for social distancing; I’ve heard rumors that something more rigorous might be coming, in the hope of really flattening that infamous curve. There are lots of wry jokes and memes about readers or introverts or others whose habits and preferences mean they have been “preparing for this moment our whole lives.” We live a pretty quiet life ourselves, so to some extent this is true of us as well (though not of Maddie, who like many young people is going to be very well served by the various ways she and her friends can stay in touch virtually). It’s pretty different having to stay home, though, and also worrying whenever you go out, even if it’s only for essentials. It’s also not spring yet here–I envy my family in Vancouver the softening weather that makes walks and parks and gardens good options. I am grateful, though, that we are comfortable and together and, so far, healthy. I am also glad I did pick up An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good, because I finished reading it this morning and it is a nice bit of twisted fun…about which more soon, I hope! Given the cyclical nature of the academic life as well as the recurrence of texts and topics in the classes I teach most often, there are lots of things I might be saying “Not again!” about! This week, however, the particularly irksome repetition is the disruption to the start of term thanks to a big storm–not

Given the cyclical nature of the academic life as well as the recurrence of texts and topics in the classes I teach most often, there are lots of things I might be saying “Not again!” about! This week, however, the particularly irksome repetition is the disruption to the start of term thanks to a big storm–not  So what, besides calming my nerves (and perhaps theirs as well), is on the agenda for our remaining classes this week? Well, in British Literature After 1800 Friday will be our (deferred) Wordsworth day. In my opening lecture on Monday I emphasized the arbitrariness of literary periods and the challenges of telling coherent stories based on chronology, the way a survey course is set up to do. But I also stressed the value of knowing when things were written, both because putting them in order is useful for understanding the way literary conversations and influences unfold, with writers often responding or reacting to or resisting each other, and because historical contexts can be crucial to recognizing meaning. My illustrative text for this point was Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud,” which (as I told them) is the first poem I ever memorized, as a child. It was perfectly intelligible to me then, and it is still a charming and accessible poem to readers who know nothing at all about what we now call ‘Romanticism.’ Without historical context, it seems anything but radical–and yet Wordsworth in his day (at least, in his early days) was considered literally revolutionary. His poetry “is one of the innovations of the time,” William Hazlitt wrote in “The Spirit of the Age”;

So what, besides calming my nerves (and perhaps theirs as well), is on the agenda for our remaining classes this week? Well, in British Literature After 1800 Friday will be our (deferred) Wordsworth day. In my opening lecture on Monday I emphasized the arbitrariness of literary periods and the challenges of telling coherent stories based on chronology, the way a survey course is set up to do. But I also stressed the value of knowing when things were written, both because putting them in order is useful for understanding the way literary conversations and influences unfold, with writers often responding or reacting to or resisting each other, and because historical contexts can be crucial to recognizing meaning. My illustrative text for this point was Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud,” which (as I told them) is the first poem I ever memorized, as a child. It was perfectly intelligible to me then, and it is still a charming and accessible poem to readers who know nothing at all about what we now call ‘Romanticism.’ Without historical context, it seems anything but radical–and yet Wordsworth in his day (at least, in his early days) was considered literally revolutionary. His poetry “is one of the innovations of the time,” William Hazlitt wrote in “The Spirit of the Age”; In 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Pride and Prejudice, though I’ll start with an abbreviated version of the lecture I would have given on Wednesday on the history of the 19th-century novel. It has been several years since I’ve taught Pride and Prejudice (

In 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Pride and Prejudice, though I’ll start with an abbreviated version of the lecture I would have given on Wednesday on the history of the 19th-century novel. It has been several years since I’ve taught Pride and Prejudice ( There’s no doubt that if I were teaching Mansfield Park these questions would be a big part of our discussion, as they are when I teach The Moonstone. I haven’t so far arrived at any ideas about how — or, to some extent, why — we would take up this specific line of inquiry in our work on Pride and Prejudice. Perhaps I am too prone to let the novels I assign set their own terms for our analysis–to rely on their overt topical engagements more than what they leave out or obscure–but this particular novel doesn’t seem to be about race and empire, even though its characters live in a world where these things (while never, I think, explicitly mentioned) matter a lot. Beyond acknowledging that fact,

There’s no doubt that if I were teaching Mansfield Park these questions would be a big part of our discussion, as they are when I teach The Moonstone. I haven’t so far arrived at any ideas about how — or, to some extent, why — we would take up this specific line of inquiry in our work on Pride and Prejudice. Perhaps I am too prone to let the novels I assign set their own terms for our analysis–to rely on their overt topical engagements more than what they leave out or obscure–but this particular novel doesn’t seem to be about race and empire, even though its characters live in a world where these things (while never, I think, explicitly mentioned) matter a lot. Beyond acknowledging that fact,  In retrospect, I’m glad my pitch for a article reporting back on the George Eliot Bicentenary Conference was rejected: the cognitive dissonance I struggled with during the conference was strong enough that I have been puzzling over how or whether to write about it even here, in relative obscurity and without being answerable to anyone else for whatever it is that I come up with to say.

In retrospect, I’m glad my pitch for a article reporting back on the George Eliot Bicentenary Conference was rejected: the cognitive dissonance I struggled with during the conference was strong enough that I have been puzzling over how or whether to write about it even here, in relative obscurity and without being answerable to anyone else for whatever it is that I come up with to say.

Each of the presenters on our panel addressed quite a different “application” for George Eliot. I spoke about what I see as reasons for but also the difficulties with “pitching” her work to the kind of bookish public I have been trying to write for–at left is my design for a George Eliot tote bag meant to illustrate the case I made that her books are not, as too often assumed,

Each of the presenters on our panel addressed quite a different “application” for George Eliot. I spoke about what I see as reasons for but also the difficulties with “pitching” her work to the kind of bookish public I have been trying to write for–at left is my design for a George Eliot tote bag meant to illustrate the case I made that her books are not, as too often assumed,

It isn’t exactly that I want no part of it, though. As I hope I have also made clear here over the years, my own intellectual life has been shaped and enriched by many kinds of academic scholarship (though

It isn’t exactly that I want no part of it, though. As I hope I have also made clear here over the years, my own intellectual life has been shaped and enriched by many kinds of academic scholarship (though  I have been very glad to see eloquent and well-informed responses to Ron Srigley’s screed “Pass, Fail” in The Walrus (which largely reiterates his screed in the Los Angeles Review of Books). I was disappointed in both venues, frankly: it seems to me to show poor editorial judgment to publish rants of this kind without checking their intemperate anecdata and wild generalizations against at least a broader sampling of facts and opinions about the very complex business that is higher education. I would have expected both journals to think better of themselves and their readers. Both

I have been very glad to see eloquent and well-informed responses to Ron Srigley’s screed “Pass, Fail” in The Walrus (which largely reiterates his screed in the Los Angeles Review of Books). I was disappointed in both venues, frankly: it seems to me to show poor editorial judgment to publish rants of this kind without checking their intemperate anecdata and wild generalizations against at least a broader sampling of facts and opinions about the very complex business that is higher education. I would have expected both journals to think better of themselves and their readers. Both  But then I realized that I have said so, that I have made my argument — over and over, for almost 10 years. Here at Novel Readings I have posted regularly about my teaching, for instance, since 2007, when I began my series on

But then I realized that I have said so, that I have made my argument — over and over, for almost 10 years. Here at Novel Readings I have posted regularly about my teaching, for instance, since 2007, when I began my series on

My

My

My first-year students are beginners in some obvious ways. All term I have been trying to work with them in a way that recognizes that for most of them, not just the readings but the kind of writing they’re being asked for is more or less unfamiliar, and I’ve tried hard to provide steps and supports and suggestions that will help them get better at it all. This careful scaffolding comes with the territory for introductory classes. What I hadn’t quite anticipated, or thought as much about, is that in some ways my graduate students are also beginners. For instance, most of them have read very little, if any, George Eliot before. I’m finding this situation trickier to address pedagogically, because the strategies I would usually use to lead undergraduate students towards greater expertise seem out of place (not just more lecturing but also things like worksheets, exercises, or tests). Even for readers who are already quite sophisticated, four George Eliot novels in a relatively short time is a lot to wrap your head around, and the specialized academic articles we’re reading alongside the novels are not that helpful for just getting oriented. I feel rather as if I threw them right in the deep end, and though they are staying afloat, that is almost as much as I ought to expect from them. (I’m not sure how to finish that thought using the same metaphor – they won’t be doing any fancy diving? they’re not about to swim laps?) This is a criticism of me and my preparations for the class, not of my students. When (if) I teach another graduate seminar, I may structure it somewhat differently — though at this point I’m not really sure how. This time around, all I can do is be as explicit and helpful as possible. I will be their flotation device! (I can’t help it: “We all of us … get our thoughts entangled in metaphors, and act fatally on the strength of them.”)

My first-year students are beginners in some obvious ways. All term I have been trying to work with them in a way that recognizes that for most of them, not just the readings but the kind of writing they’re being asked for is more or less unfamiliar, and I’ve tried hard to provide steps and supports and suggestions that will help them get better at it all. This careful scaffolding comes with the territory for introductory classes. What I hadn’t quite anticipated, or thought as much about, is that in some ways my graduate students are also beginners. For instance, most of them have read very little, if any, George Eliot before. I’m finding this situation trickier to address pedagogically, because the strategies I would usually use to lead undergraduate students towards greater expertise seem out of place (not just more lecturing but also things like worksheets, exercises, or tests). Even for readers who are already quite sophisticated, four George Eliot novels in a relatively short time is a lot to wrap your head around, and the specialized academic articles we’re reading alongside the novels are not that helpful for just getting oriented. I feel rather as if I threw them right in the deep end, and though they are staying afloat, that is almost as much as I ought to expect from them. (I’m not sure how to finish that thought using the same metaphor – they won’t be doing any fancy diving? they’re not about to swim laps?) This is a criticism of me and my preparations for the class, not of my students. When (if) I teach another graduate seminar, I may structure it somewhat differently — though at this point I’m not really sure how. This time around, all I can do is be as explicit and helpful as possible. I will be their flotation device! (I can’t help it: “We all of us … get our thoughts entangled in metaphors, and act fatally on the strength of them.”)