Reading

It took some effort and some strategic skimming, but I made it to the end of Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads. There’s a lot of it – but that wouldn’t have been a problem if I had felt there was more to it. What was all that accumulated information for, in the end? What comes of it? What are we left thinking about, after wading through so much detail about people who are by and large quite unsympathetic and disappointingly static? I was never exactly bored, but I was also completely unable to get my bearings at anything but the most literal level. But a lot of astute critics loved the novel (that’s one reason I bought it, after not having read anything by Franzen since The Corrections) so as always we are left with the great mystery of reading, the inexplicable idiosyncrasy of it all.

It took some effort and some strategic skimming, but I made it to the end of Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads. There’s a lot of it – but that wouldn’t have been a problem if I had felt there was more to it. What was all that accumulated information for, in the end? What comes of it? What are we left thinking about, after wading through so much detail about people who are by and large quite unsympathetic and disappointingly static? I was never exactly bored, but I was also completely unable to get my bearings at anything but the most literal level. But a lot of astute critics loved the novel (that’s one reason I bought it, after not having read anything by Franzen since The Corrections) so as always we are left with the great mystery of reading, the inexplicable idiosyncrasy of it all.

Now I’m reading Graeme Macrae Burnet’s Case Study. I think it first caught my eye because it was on the Booker longlist. Then I read something else about it somewhere – now I can’t remember exactly what or where (typical of me these days, I’m sorry to say) that sharpened my interest enough that I went ahead and procured it. I’m engaged but not engrossed so far; we’ll see how it goes. I reviewed Burnet’s earlier novel His Bloody Project for Open Letters Monthly a few years ago and concluded it was “not wholly satisfying.” It too was a compilation of purported source documents; my main complaint (besides the voices being insufficiently distinct and exciting) was that it lacked a unifying idea about its elements. Maybe this should have discouraged me from trying another novel by the same author in so similar a vein, but Case Study seems tauter so far. I’ll see. If I can just concentrate on it long enough to read to the end, that in itself will be a mark in its favor.

Update: I did read Case Study to the end, and stayed interested in it the whole time. Success, then! I am not sure I read it in a suspicious enough way: I found the ending curiously anticlimactic and it was only on peering at some reviews that I started to think about more layers of unreliability and thus interpretation than had occurred to me on my own. Curiosity, too, rather than emotional engagement, was my main feeling as I read: I wanted to see how the elements were going to come together, and what they were going to mean, but I wasn’t particularly invested in the outcome otherwise. It’s a clever book, maybe too clever for a reader like me whose first instinct, at some level, is to give myself over to the fiction, rather than to mistrust every move.*

Also on my TBR pile are Ian McEwan’s Lessons, which my book club is doing next and Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land, which a member of my book club talked about in such an interesting way at our last meeting that it inspired me to pick it up. I’m stalled about a third of the way into Andrew Greig’s Rose Nicolson, and keep looking at but not actually starting Nicola Griffith’s Spear. I feel as if I keep picking the wrong books, as if my reading radar is malfunctioning. For this reason I am suppressing my urge to rush out and buy Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, even though everything I’ve heard about it so far makes it sound very tempting. Or maybe my “bandwidth,” as we like to call it nowadays, is just overwhelmed by the combination of work (which of course includes a lot of reading) and grief.

Also on my TBR pile are Ian McEwan’s Lessons, which my book club is doing next and Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land, which a member of my book club talked about in such an interesting way at our last meeting that it inspired me to pick it up. I’m stalled about a third of the way into Andrew Greig’s Rose Nicolson, and keep looking at but not actually starting Nicola Griffith’s Spear. I feel as if I keep picking the wrong books, as if my reading radar is malfunctioning. For this reason I am suppressing my urge to rush out and buy Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, even though everything I’ve heard about it so far makes it sound very tempting. Or maybe my “bandwidth,” as we like to call it nowadays, is just overwhelmed by the combination of work (which of course includes a lot of reading) and grief.

Reflections

Today is exactly one year since Owen moved back in with us, for what was meant to be a restorative stop-gap measure while we sorted out his next steps. The onset of fall weather, with its crisp sunshine and bright colours, has intensified the feeling I’ve talked about before of time coming somehow full circle: the intervening months have been so strange, so foggy and disoriented, and the events of this time last year are still so immediate and vivid in my mind, that it is almost easier to believe I am still there, in November 2021, than here, helplessly reaching back to that hopeful reunion across the unfathomable chasm Owen’s death created in my life and my memories. But I’m not there, of course, but here, and soon there will be other, even harder, markers of the relentless way time puts more and more distance between us. I think often of Denise Riley’s comment that “the dead slip away, as we realize that we have unwillingly left them behind in their timelessness.” Current wisdom is that grief is best treated by finding ways to continue our relationships with those we have lost. It is an ongoing struggle, for me, to understand what that means in practice, although I am learning that it includes grief itself, which for now at least is the truest expression of my ongoing love for my son. Its pain is no less fierce now, but it is at least more familiar.

Today is exactly one year since Owen moved back in with us, for what was meant to be a restorative stop-gap measure while we sorted out his next steps. The onset of fall weather, with its crisp sunshine and bright colours, has intensified the feeling I’ve talked about before of time coming somehow full circle: the intervening months have been so strange, so foggy and disoriented, and the events of this time last year are still so immediate and vivid in my mind, that it is almost easier to believe I am still there, in November 2021, than here, helplessly reaching back to that hopeful reunion across the unfathomable chasm Owen’s death created in my life and my memories. But I’m not there, of course, but here, and soon there will be other, even harder, markers of the relentless way time puts more and more distance between us. I think often of Denise Riley’s comment that “the dead slip away, as we realize that we have unwillingly left them behind in their timelessness.” Current wisdom is that grief is best treated by finding ways to continue our relationships with those we have lost. It is an ongoing struggle, for me, to understand what that means in practice, although I am learning that it includes grief itself, which for now at least is the truest expression of my ongoing love for my son. Its pain is no less fierce now, but it is at least more familiar.

These lines by Philip Larkin capture so well what it feels like to live with sorrow, sometimes sitting quietly with it but sometimes sensing it stir, or stirring it yourself, so that it flares up once more, rending your heart. I know a lot of you live this way too.

If grief could burn out

Like a sunken coal,

The heart would rest quiet,

The unrent soul

Be still as a veil;

But I have watched all night

The fire grow silent,

The grey ash soft:

And I stir the stubborn flint

The flames have left,

And grief stirs, and the deft

Heart lies impotent.

* One of the challenges of a novel like Case Study for me is that, deliberately, we are discouraged from accepting any of it as sincere. And yet in the midst of it, there was a passage – narrated by a character we can’t trust, about someone who by the end of the novel I’m not 100% sure ever actually existed within its fictional space – that hit very hard:

Then something else occurred. One evening, as we sat at supper, I turned to the place Veronica had lately occupied and was about to say something to her, before I checked myself. For the first time, I keenly felt her absence. From that moment, I saw her death in a different light. There was a Veronica-sized void in the world. As well as her physical presence, the contents of her mind were gone. The question I had been about to ask would never be answered. Everything she had learned, the memories she had accumulated, her future thoughts and actions had all been snuffed out. The world was diminished by her non-existence.

In the novel, this moment is either poignant autobiography or strategically affecting fantasy (or, perhaps, sadly troubling delusion). Whichever of these it is meant as, it’s also, in its own way, truthful, as are many of Burnet’s remarks – off-hand though they seem – about suicide and “dark thoughts.”

Comparisons are foolish, I know, but often these days I recoil uncomfortably from cheerful exchanges among my many bookish ‘tweeps’ about what they’ve been reading because they seem to read so much and so enthusiastically—which is great, of course, but because I’m struggling to finish most of the books I pick up, the contrast can make me feel discouraged instead of interested and inspired. Social media has a way of making you feel inadequate or alienated, doesn’t it? And I say this as someone who has long championed Twitter (and would still do so, if challenged) on the grounds that it is very much what you make it. “My” Twitter is full of avid readers and I love that about it. It’s absolutely not their fault that lately it sometimes seems to hurt as much as it helps. I’m trying to think of it as aspirational: one day, I too will feel cheerfully bookish again!

Comparisons are foolish, I know, but often these days I recoil uncomfortably from cheerful exchanges among my many bookish ‘tweeps’ about what they’ve been reading because they seem to read so much and so enthusiastically—which is great, of course, but because I’m struggling to finish most of the books I pick up, the contrast can make me feel discouraged instead of interested and inspired. Social media has a way of making you feel inadequate or alienated, doesn’t it? And I say this as someone who has long championed Twitter (and would still do so, if challenged) on the grounds that it is very much what you make it. “My” Twitter is full of avid readers and I love that about it. It’s absolutely not their fault that lately it sometimes seems to hurt as much as it helps. I’m trying to think of it as aspirational: one day, I too will feel cheerfully bookish again! Earlier this month I read Elizabeth Jane Howard’s The Light Years, the first of her much-admired Cazalet Chronicles. I enjoyed it just fine but wasn’t swept up in it—or swept away by it! The aspect of it that surprised me the most was how much it read like a book written in the 1930s (or perhaps the 1950s) rather than in the 1990s: it felt very much of the time it depicts. As a result, in some ways it seemed like a missed opportunity, artistically speaking: it’s a smart, elegant, readable portrayal but it didn’t seem to have any layers of reflection, or to take advantage of being what it actually is, namely historical fiction. Maybe the idea was to give us the feeling of being transported back, rather than to encourage us to look back and consider gaps and differences. I already had a copy of the second book in the series, Marking Time, and I will probably read it eventually, but I’ve picked it up, read a few pages, and put it down again more than once: I just don’t feel compelled to persist. The last time I tried, I found myself thinking that (deliberately or not) it read like the novel I imagine Woolf was trying not to write when she wrote what ended up as The Years. The problem, she noted, was “how to give ordinary waking Arnold Bennett life the form of art.” Not (we might conclude, following her lead) by just recounting in meticulous detail everything that happens to a large number of people over a long period of time.

Earlier this month I read Elizabeth Jane Howard’s The Light Years, the first of her much-admired Cazalet Chronicles. I enjoyed it just fine but wasn’t swept up in it—or swept away by it! The aspect of it that surprised me the most was how much it read like a book written in the 1930s (or perhaps the 1950s) rather than in the 1990s: it felt very much of the time it depicts. As a result, in some ways it seemed like a missed opportunity, artistically speaking: it’s a smart, elegant, readable portrayal but it didn’t seem to have any layers of reflection, or to take advantage of being what it actually is, namely historical fiction. Maybe the idea was to give us the feeling of being transported back, rather than to encourage us to look back and consider gaps and differences. I already had a copy of the second book in the series, Marking Time, and I will probably read it eventually, but I’ve picked it up, read a few pages, and put it down again more than once: I just don’t feel compelled to persist. The last time I tried, I found myself thinking that (deliberately or not) it read like the novel I imagine Woolf was trying not to write when she wrote what ended up as The Years. The problem, she noted, was “how to give ordinary waking Arnold Bennett life the form of art.” Not (we might conclude, following her lead) by just recounting in meticulous detail everything that happens to a large number of people over a long period of time. Also this month I finally got my hands on Sarah Moss’s The Fell. I’m a big admirer of Moss’s fiction (see

Also this month I finally got my hands on Sarah Moss’s The Fell. I’m a big admirer of Moss’s fiction (see  My book club met in the middle of September to talk about Emily St. John Mandel’s

My book club met in the middle of September to talk about Emily St. John Mandel’s  Then I read David Nicholls’s Us, which I happened to have recently downloaded, inspired by having enjoyed the TV adaptation starring Tom Hollander (which I thought was excellent). I wouldn’t say it’s a great novel, or even a particularly good one, at least in the prose: it’s a bit awkward and heavy-handed. I really empathized with its protagonist Douglas, though, and I appreciate that Nicholls refused the simplistic happy ending you might expect from a novel about a man hoping to save his marriage while going on a ‘grand tour’ with his wife and son.

Then I read David Nicholls’s Us, which I happened to have recently downloaded, inspired by having enjoyed the TV adaptation starring Tom Hollander (which I thought was excellent). I wouldn’t say it’s a great novel, or even a particularly good one, at least in the prose: it’s a bit awkward and heavy-handed. I really empathized with its protagonist Douglas, though, and I appreciate that Nicholls refused the simplistic happy ending you might expect from a novel about a man hoping to save his marriage while going on a ‘grand tour’ with his wife and son.

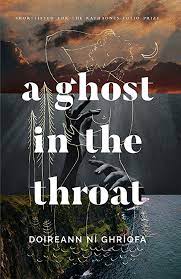

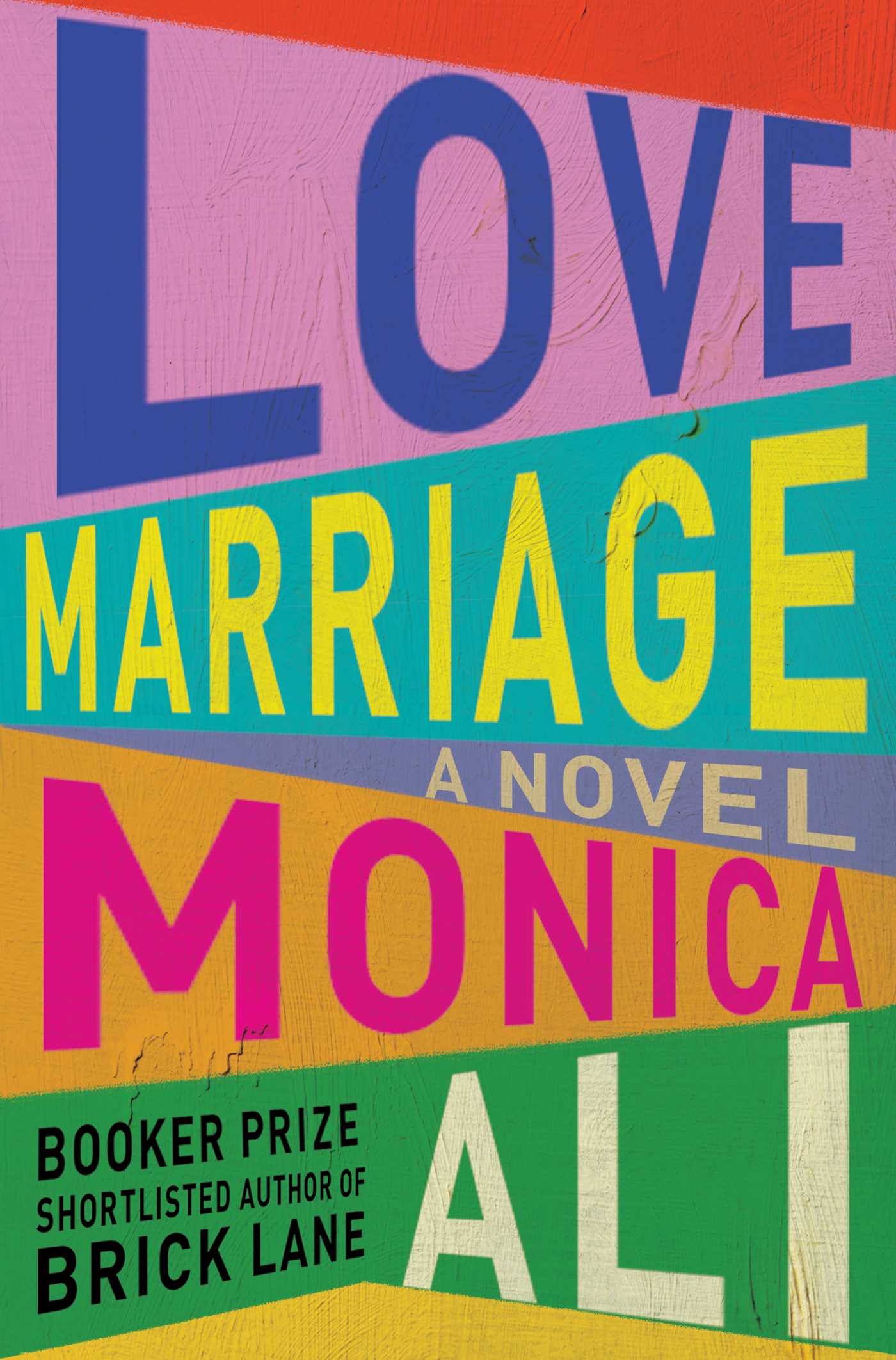

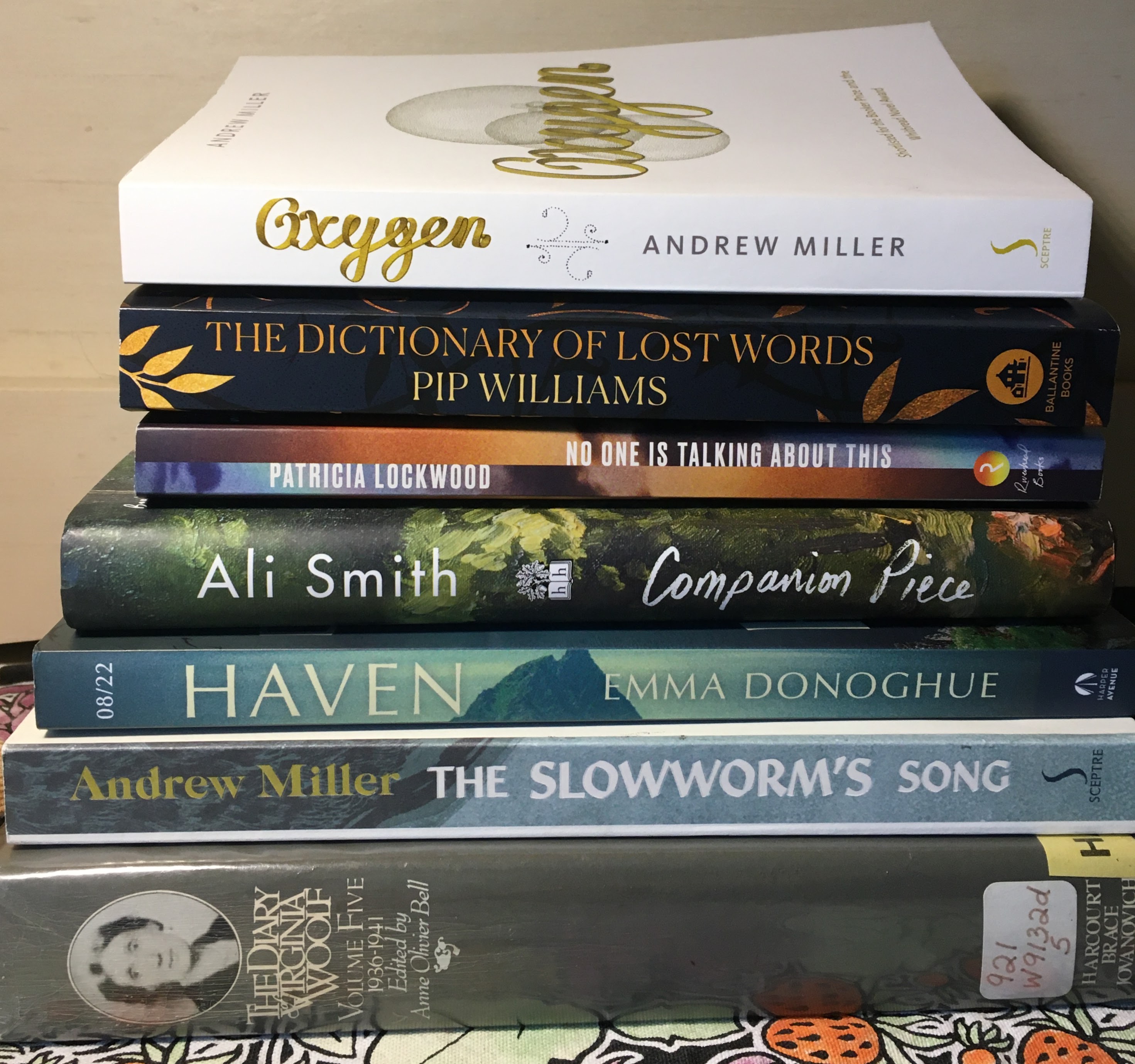

July was not a very good reading month for me. By habit and on principle I usually finish most of the books I start, at least if I have any reason to think they are worth a bit of effort if it’s needed. In July, however, I not only didn’t even start many books (not by my usual standards, anyway) but I set aside almost as many books as I completed—Bloomsbury Girls (which hit all my sweet spots in theory but fell painfully flat in practice), Gilead (a reread I was enthusiastic about at first but just could not persist with), A Ghost in the Throat (which I will try again, as I liked its voice—what I struggled with was its essentialism and its somewhat miscellaneous or wandering structure). I already mentioned Andrew Miller’s Oxygen and Monica Ali’s Love Marriage, both of which I finished and enjoyed,

July was not a very good reading month for me. By habit and on principle I usually finish most of the books I start, at least if I have any reason to think they are worth a bit of effort if it’s needed. In July, however, I not only didn’t even start many books (not by my usual standards, anyway) but I set aside almost as many books as I completed—Bloomsbury Girls (which hit all my sweet spots in theory but fell painfully flat in practice), Gilead (a reread I was enthusiastic about at first but just could not persist with), A Ghost in the Throat (which I will try again, as I liked its voice—what I struggled with was its essentialism and its somewhat miscellaneous or wandering structure). I already mentioned Andrew Miller’s Oxygen and Monica Ali’s Love Marriage, both of which I finished and enjoyed,  Ali Smith’s how to be both was a mixed experience for me. My copy began with the contemporary story (as you may know, two versions were published), and it read easily for me and was quite engaging, in the same way that the

Ali Smith’s how to be both was a mixed experience for me. My copy began with the contemporary story (as you may know, two versions were published), and it read easily for me and was quite engaging, in the same way that the  Another reread for me in July was Yiyun Li’s

Another reread for me in July was Yiyun Li’s  Since I

Since I

Anyway, this is a pretty roundabout way to get to the point of this post, which is to update the record of my recent reading, if only to shore up my recollections of this period of my life. There’s no way I can write “proper” posts about each of these recently read titles, but I don’t want to forget that I read them, and I also (as part of my larger effort to “reengage with the world”) want to push myself past the sad inertia that at this point is mostly to blame for my losing the habit of writing up my ‘novel readings.’ I remind myself, not for the first time, of my conviction that if something was worth doing before a catastrophe,

Anyway, this is a pretty roundabout way to get to the point of this post, which is to update the record of my recent reading, if only to shore up my recollections of this period of my life. There’s no way I can write “proper” posts about each of these recently read titles, but I don’t want to forget that I read them, and I also (as part of my larger effort to “reengage with the world”) want to push myself past the sad inertia that at this point is mostly to blame for my losing the habit of writing up my ‘novel readings.’ I remind myself, not for the first time, of my conviction that if something was worth doing before a catastrophe,

I have stumbled more in the last couple of weeks, starting and then quitting a lot of titles including Sarah Hall’s Burntcoat and Rachel Cusk’s Second Place, but I did read Monica Ali’s Love Marriage with interest that (with a bit of persistence) grew into appreciation. One book I began with enthusiasm but ultimately decided not to finish was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, which I have read before, long ago (pre-blogging, that’s how long ago!). It was just too religious for me this time: I just don’t see the world as John Ames does, and while as a well-trained and very experienced novel reader I totally understand and agree that I don’t have to in order to engage with his story, this time (with apologies to the people of faith among you) it just felt too much like having to take very seriously someone who believes in

I have stumbled more in the last couple of weeks, starting and then quitting a lot of titles including Sarah Hall’s Burntcoat and Rachel Cusk’s Second Place, but I did read Monica Ali’s Love Marriage with interest that (with a bit of persistence) grew into appreciation. One book I began with enthusiasm but ultimately decided not to finish was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, which I have read before, long ago (pre-blogging, that’s how long ago!). It was just too religious for me this time: I just don’t see the world as John Ames does, and while as a well-trained and very experienced novel reader I totally understand and agree that I don’t have to in order to engage with his story, this time (with apologies to the people of faith among you) it just felt too much like having to take very seriously someone who believes in  The past few weeks, though still often sad and difficult, have been a bit better for reading. I’m not sure if it’s me or the books—probably a bit of both.

The past few weeks, though still often sad and difficult, have been a bit better for reading. I’m not sure if it’s me or the books—probably a bit of both. I didn’t much like Andrew Sean Greer’s Less. I persisted to the end, but it never engaged me deeply at all. My least favorite quality in a book is archness, and that seemed to me Less‘s primary mood. It will shock some of my Twitter friends when I say that I also didn’t much like Laurie Colwin’s Happy All The Time: it isn’t arch, exactly, but it is crisp and clever and detached to the point that it felt thin, even superficial, and thus unsatisfying. I was interested in the premise of Kate Grenville’s A House Made of Leaves and there are good things about it, but overall the execution felt dry and the messages (about history and gender and colonialism) perfunctory, delivered rather than dramatized.

I didn’t much like Andrew Sean Greer’s Less. I persisted to the end, but it never engaged me deeply at all. My least favorite quality in a book is archness, and that seemed to me Less‘s primary mood. It will shock some of my Twitter friends when I say that I also didn’t much like Laurie Colwin’s Happy All The Time: it isn’t arch, exactly, but it is crisp and clever and detached to the point that it felt thin, even superficial, and thus unsatisfying. I was interested in the premise of Kate Grenville’s A House Made of Leaves and there are good things about it, but overall the execution felt dry and the messages (about history and gender and colonialism) perfunctory, delivered rather than dramatized. I have some promising options in my TBR pile to choose from next, including Nicola Griffith’s Spear (a sequel to

I have some promising options in my TBR pile to choose from next, including Nicola Griffith’s Spear (a sequel to  The last three months haven’t been very good reading months for me: I have picked up and then put back down a lot more books than I have finished. This is true of new (to me) books, at any rate: since January I have actually reread quite a few books that were easy and comforting, including the first four Anne books (thanks to a dear friend who sent me a lovely box set), several favorite romances and mysteries, and The Beethoven Medal (part of one of

The last three months haven’t been very good reading months for me: I have picked up and then put back down a lot more books than I have finished. This is true of new (to me) books, at any rate: since January I have actually reread quite a few books that were easy and comforting, including the first four Anne books (thanks to a dear friend who sent me a lovely box set), several favorite romances and mysteries, and The Beethoven Medal (part of one of  In January, I read Lauren Groff’s Matrix. I expected to like it more than I did. This is not to say I didn’t like it; the premise was fascinating, and I remember being impressed at how vividly Groff built her world, and how strong, strange, and specific she made Marie as a character. Female agency and empowerment, creativity, desire, spirituality: the book explores them all, with a compelling combination of grittiness and lyricism. For some reason, though, I was disappointed when I learned that this particular work of historical fiction is much more fictional than historical—that almost nothing is actually known about Marie, that Groff’s character and story is all invention. This retroactively took some of the life out of the book for me, which is hardly fair given that I read and love a lot of historical fiction that is mostly made up.

In January, I read Lauren Groff’s Matrix. I expected to like it more than I did. This is not to say I didn’t like it; the premise was fascinating, and I remember being impressed at how vividly Groff built her world, and how strong, strange, and specific she made Marie as a character. Female agency and empowerment, creativity, desire, spirituality: the book explores them all, with a compelling combination of grittiness and lyricism. For some reason, though, I was disappointed when I learned that this particular work of historical fiction is much more fictional than historical—that almost nothing is actually known about Marie, that Groff’s character and story is all invention. This retroactively took some of the life out of the book for me, which is hardly fair given that I read and love a lot of historical fiction that is mostly made up. In February, I read through Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet. The sabbatical project I am picking away at has to do with the relationship between fictional form and social or political engagement (or, to put it another way, with fictional form as itself a kind of social or political engagement). With this in mind I was poking around in information about the Orwell Prize and this led me to some articles and interviews about Smith’s win, which in turn made me curious about whether her series might make a good contemporary example for me. I reread Autumn, and then picked up the other three and read them all through. By the end of Spring I was a bit less sure about using this series for my purposes, but some of my hesitation came from feeling unqualified to work on Smith: both her style and her influences, including the explicit invocation of Shakespeare plays, are a bit far afield for me. That doesn’t rule the books out, of course; it would just mean I would have to work hard to figure out how to talk about them, a prospect which is actually kind of appealing, or it would be if my mind didn’t feel so scattered all the time right now.

In February, I read through Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet. The sabbatical project I am picking away at has to do with the relationship between fictional form and social or political engagement (or, to put it another way, with fictional form as itself a kind of social or political engagement). With this in mind I was poking around in information about the Orwell Prize and this led me to some articles and interviews about Smith’s win, which in turn made me curious about whether her series might make a good contemporary example for me. I reread Autumn, and then picked up the other three and read them all through. By the end of Spring I was a bit less sure about using this series for my purposes, but some of my hesitation came from feeling unqualified to work on Smith: both her style and her influences, including the explicit invocation of Shakespeare plays, are a bit far afield for me. That doesn’t rule the books out, of course; it would just mean I would have to work hard to figure out how to talk about them, a prospect which is actually kind of appealing, or it would be if my mind didn’t feel so scattered all the time right now. In March I read Denise Mina’s Rizzio, another historical novel I ended up being a bit disappointed in. There was something awkward (to my reading ear, anyway) about the combination of meticulous historical detail and a too-contemporary idiom, especially in the dialogue. Mina is good at foreboding and action, as you’d expect from a crime novelist. I reread Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont, which I loved all over again, though it is even more melancholy than I’d remembered. Then I read Louise Erdrich’s The Sentence, which went really well at first and then started (I thought) to lose its focus and ended up feeling scattered, full of good bits but not a satisfying whole. I read two recently reissued novels by Rosalind Brackenbury, A Day to Remember to Forget and A Virtual Image, for an upcoming review (I finished a third, Into Egypt, yesterday). My last March book was Katherine Ashenburg’s Her Turn, which I enjoyed a lot. It’s less ambitious than some of my other recent reading, but it seemed to me to do well what it set out to do, including explore the possibilities and implications of both revenge and forgiveness in the context of our most intimate relationships.

In March I read Denise Mina’s Rizzio, another historical novel I ended up being a bit disappointed in. There was something awkward (to my reading ear, anyway) about the combination of meticulous historical detail and a too-contemporary idiom, especially in the dialogue. Mina is good at foreboding and action, as you’d expect from a crime novelist. I reread Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont, which I loved all over again, though it is even more melancholy than I’d remembered. Then I read Louise Erdrich’s The Sentence, which went really well at first and then started (I thought) to lose its focus and ended up feeling scattered, full of good bits but not a satisfying whole. I read two recently reissued novels by Rosalind Brackenbury, A Day to Remember to Forget and A Virtual Image, for an upcoming review (I finished a third, Into Egypt, yesterday). My last March book was Katherine Ashenburg’s Her Turn, which I enjoyed a lot. It’s less ambitious than some of my other recent reading, but it seemed to me to do well what it set out to do, including explore the possibilities and implications of both revenge and forgiveness in the context of our most intimate relationships.

It has been quiet at Novel Readings this week but that’s not because I haven’t been reading! It’s more that there hasn’t seemed to be much to say about the reading I’ve been doing. My recent novel reading has mostly been rereading: Rosy Thornton’s

It has been quiet at Novel Readings this week but that’s not because I haven’t been reading! It’s more that there hasn’t seemed to be much to say about the reading I’ve been doing. My recent novel reading has mostly been rereading: Rosy Thornton’s  Those are the novels I’ve reread for “fun” (though as I’ve said before, it is never 100% clear to me

Those are the novels I’ve reread for “fun” (though as I’ve said before, it is never 100% clear to me  The other reading I’ve been doing pretty steadily is also for research purposes, but with an eye to my teaching rather than my writing: I’m always gathering up references to new or (to me) unfamiliar scholarship in, around, and about “my” field, and at intervals I resolve to dig into it and see what else I could or should be talking about in the classroom, or just thinking about. Since the end of term I’ve been trying to go through 2-3 articles a day from that folder. This exercise tends to be equal parts exhilarating and exhausting: I enjoy feeling as if I’m learning new things or seeing familiar things from fresh angles, but I have long had

The other reading I’ve been doing pretty steadily is also for research purposes, but with an eye to my teaching rather than my writing: I’m always gathering up references to new or (to me) unfamiliar scholarship in, around, and about “my” field, and at intervals I resolve to dig into it and see what else I could or should be talking about in the classroom, or just thinking about. Since the end of term I’ve been trying to go through 2-3 articles a day from that folder. This exercise tends to be equal parts exhilarating and exhausting: I enjoy feeling as if I’m learning new things or seeing familiar things from fresh angles, but I have long had  I’m not sure what I’m going to read next “just” for myself. I bought Lonesome Dove as a summer treat, but I’m saving it for real summer weather: it looks perfect for reading on the deck. My book club’s next choice is Nancy Mitford’s The Blessing (we wanted something light for summer, and this was one of hers that none of us had already read)—but I don’t have it in hand yet. Of course, like everyone likely to read this post I have a number of unread books on my shelf (not as many as some of you have, though, I’m pretty sure!) but none of them look that tempting right now, which is probably why I haven’t read them already … Maybe I’ll reread something else I know I’ll like, if only to keep the temptation to order yet more new books at bay!

I’m not sure what I’m going to read next “just” for myself. I bought Lonesome Dove as a summer treat, but I’m saving it for real summer weather: it looks perfect for reading on the deck. My book club’s next choice is Nancy Mitford’s The Blessing (we wanted something light for summer, and this was one of hers that none of us had already read)—but I don’t have it in hand yet. Of course, like everyone likely to read this post I have a number of unread books on my shelf (not as many as some of you have, though, I’m pretty sure!) but none of them look that tempting right now, which is probably why I haven’t read them already … Maybe I’ll reread something else I know I’ll like, if only to keep the temptation to order yet more new books at bay!

I can’t post about books I’ve finished this week because I haven’t finished any. I’ve been trying to read–keeping in mind

I can’t post about books I’ve finished this week because I haven’t finished any. I’ve been trying to read–keeping in mind  So, one challenge is aging, and there’s not much to be done about that (and it’s only going to get worse, I know!) The other, though, has been the books I’ve been trying to focus on. Both are ones I have wanted to read for a long time, but neither has proved the right book for this moment, although one of them I am still working on. The first one I started this week was Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, which has been on my reading wish list for years. It looks great! I am sure it is great! But a couple of chapters into it, I just couldn’t bear it: it was making me feel both bored and claustrophobic. I suspect some of that is a deliberate effect, as it seems to be about a stifling world that tries to stifle people’s feelings. Bowen’s sentences didn’t help. I love Olivia Manning’s description of Bowen’s prose as being like someone drinking milk with their legs crossed behind their head: often, it just seems to be making something that’s actually fairly simple much more complicated than it needs to be!

So, one challenge is aging, and there’s not much to be done about that (and it’s only going to get worse, I know!) The other, though, has been the books I’ve been trying to focus on. Both are ones I have wanted to read for a long time, but neither has proved the right book for this moment, although one of them I am still working on. The first one I started this week was Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, which has been on my reading wish list for years. It looks great! I am sure it is great! But a couple of chapters into it, I just couldn’t bear it: it was making me feel both bored and claustrophobic. I suspect some of that is a deliberate effect, as it seems to be about a stifling world that tries to stifle people’s feelings. Bowen’s sentences didn’t help. I love Olivia Manning’s description of Bowen’s prose as being like someone drinking milk with their legs crossed behind their head: often, it just seems to be making something that’s actually fairly simple much more complicated than it needs to be!  The other is John Le Carré’s A Perfect Spy, which I am still working on. I loved

The other is John Le Carré’s A Perfect Spy, which I am still working on. I loved  So that’s where I am this week! I have been thinking a lot about posting more in my once-usual “this week in my classes” series but I can’t seem to get past the twin obstacles of my classes

So that’s where I am this week! I have been thinking a lot about posting more in my once-usual “this week in my classes” series but I can’t seem to get past the twin obstacles of my classes