In an era where Mary Cassatt eschewed marriage and a fully adult life to live with her parents in Paris so that she could produce her work, Mary Hiester bounded into an adulthood of painting with a grown-up’s problems of money and sex and logistics . . . Existing with an ambitious man in a socially constricted world for women of which a person today can barely grasp the demeaning dimensions, she lived, by her lights, “cheerfully.” She painted around the obstacles of an artist’s life by employing a woman’s emblem, the rose, and later an emblem of independence, the tree.

In an era where Mary Cassatt eschewed marriage and a fully adult life to live with her parents in Paris so that she could produce her work, Mary Hiester bounded into an adulthood of painting with a grown-up’s problems of money and sex and logistics . . . Existing with an ambitious man in a socially constricted world for women of which a person today can barely grasp the demeaning dimensions, she lived, by her lights, “cheerfully.” She painted around the obstacles of an artist’s life by employing a woman’s emblem, the rose, and later an emblem of independence, the tree.

Molly Peacock’s Flower Diary weaves together three stories—each of which is also, in its own way, more than one kind of story: there’s the biographical account of artist Mary Hiester Reid, including her marriage to and working relationship with her husband George Agnew Reid; there’s the story of Peacock’s second marriage, which is also the story of her second husband’s illness and death; and there’s the story of Mary Evelyn Wrinch, who married George Reid after the first Mary Reid’s death. “The three of them,” Peacock notes, “are even buried together

in Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery, section 18, lot 22. Not side by side, but on top of each other; MHR is the foundational layer. Then George on top of her. Last, Mary Evelyn on top of George.

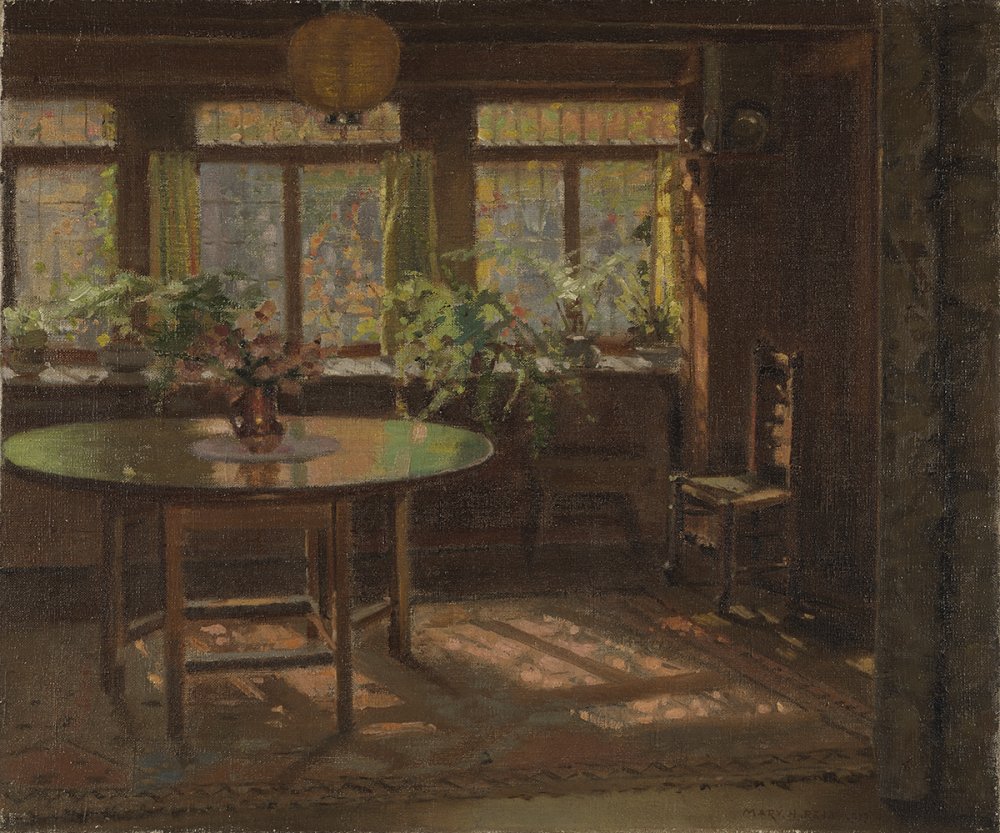

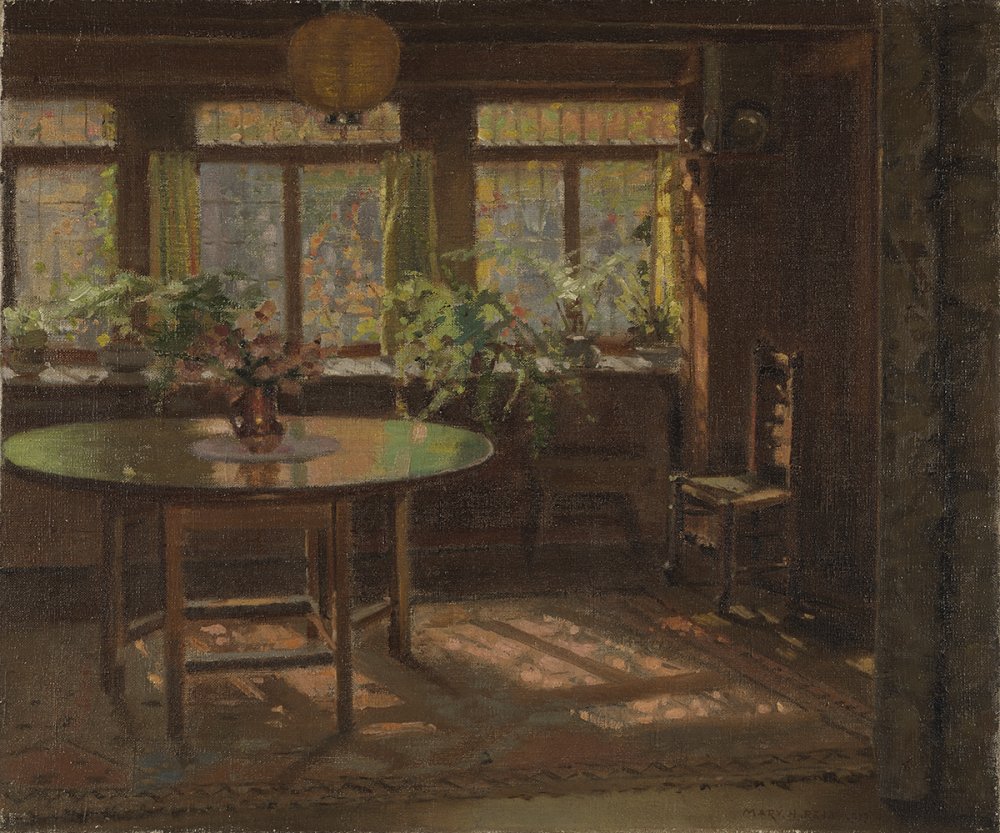

Like Peacock’s earlier, similar work The Paper Garden, the biographical and autobiographical material is interwoven with commentary on art and creativity, especially in this case Mary Hiester Reid’s paintings. For me, these were the best parts of the book. Peacock is a wonderful observer. “A Fireside is rich, warm, and pillowy,” she says of one of Mary’s early paintings:

Like Peacock’s earlier, similar work The Paper Garden, the biographical and autobiographical material is interwoven with commentary on art and creativity, especially in this case Mary Hiester Reid’s paintings. For me, these were the best parts of the book. Peacock is a wonderful observer. “A Fireside is rich, warm, and pillowy,” she says of one of Mary’s early paintings:

It’s full of interest for the beholder’s engagement (books, copper tea kettles, a Japanese print brought back from Paris, George’s copy of a huge Velazquez that Mary admired). To the side of the umber beams bloom paperwhite narcissus bulbs in a ceramic bowl. The sparkler flowers hurl out their scent in swift dashes of white that make you know it must be snowing outside. (Canadians plant them to bloom in January or February, life in the dead of winter.) Painted in 1910 when she was fifty-six, it is of a generous room where MHR lit her own art fire, warmed others, and somehow negotiated the complexities of a spiritual, aesthetic, familiar, and perhaps sexual, quasi-ménage à trois.

“Like the continent’s Depression, or perhaps her own,” she says later, of the still-life “Three Roses,”

Mary’s roses languish, looming from the dark background. One of them even drops two tear-shaped petals onto the table below. Another rose—the youngest?—barely out of the bud, has tightly folded petals. Each one is flushed, the pink of the inside of a mouth. The top flower almost pats the back of the one that has let two weeping petals go. It is a highly emotional scene—roses acting out a romance? The still life has a narrative quality.

Now that she’s described it that way, I can see it: does it make her description any less plausible that it never would have occurred to me to read so much drama into these quietly lovely flowers? I remember having similar questions about her interpretations of some of Mary Delaney’s paper flowers—and about some of the commentary in William Kloss’s ‘Great Course’ on Masterpieces of European Art. “You see, but you do not observe,” Sherlock Holmes famously chides Dr. Watson: it takes a trained eye, a sympathetic eye, perhaps a poetic eye, to see what Peacock sees. Her poet’s words, of course, also make the difference between plain description and illumination.

I found Mary’s paintings really beautiful. (Flower Diary itself is a beautiful object, with heavy, glossy pages and rich, high quality reproductions, a treat for the eyes.) I hadn’t heard of her before. Peacock explains that MHR’s influences were the “tonalists,” painters who “attempt to represent emotions in their paintings through times of day like sunrise, twilight, or sunset, and weather like fog and rain”— a key example is Whistler, whose portrait of Thomas Carlyle was a significant inspiration for MHR’s late composition “A Study in Greys.” MHR, Peacock says, “made [tonalism] her own, with a Realist’s touch”; she had “zero interest in the hard abstraction of modernism.” These labels and abstract explanations mean less to me than Peacock’s insights into the paintings as reminders “that a moment existed, that it flowered fully, that it was fraught and complex, and that a woman in a lace collar holding a palette insisted on its essence.”

Flower Diary follows Mary’s artistic development, integrating it with the story of her personal life—as indeed the two were intricately related in reality. There are lots of parts to both, including the art school Mary and George ran and many trips to Paris and Spain and time spent in an artistic community in Onteora, in the Catskills. Peacock emphasizes Mary’s “persistence” as an artist. Hers was not a bad marriage, or an unsuccessful career: George was a supportive partner, and she was productive and accomplished and recognized. The times were not kind to ambitious women in general, though, or to women artists more particularly. “I don’t know where the assurance and conviction required for Mary’s sort of persistence comes from precisely,” Peacock comments,

Flower Diary follows Mary’s artistic development, integrating it with the story of her personal life—as indeed the two were intricately related in reality. There are lots of parts to both, including the art school Mary and George ran and many trips to Paris and Spain and time spent in an artistic community in Onteora, in the Catskills. Peacock emphasizes Mary’s “persistence” as an artist. Hers was not a bad marriage, or an unsuccessful career: George was a supportive partner, and she was productive and accomplished and recognized. The times were not kind to ambitious women in general, though, or to women artists more particularly. “I don’t know where the assurance and conviction required for Mary’s sort of persistence comes from precisely,” Peacock comments,

but daily circumstances—the vector of a husband’s energy, an active social life, the maintaining of meals, clothes, sleep, friendship, sex, when no one expects you, a weaker vessel, to do what you do—require an internal stamina that must connect to a conviction that something inside of you will perish if you don’t protect your gift. I marvel at the ability to access emotions so thoroughly and to organize an art life, to display rage and to turn toward a canvas with plans. It is consummately adult to hold at once these contradictory responses and urges. “Going cheerfully on with the task” was her method. Eight paintings equaled health, equaled survival, equaled a truly textured life that could have disintegrated if the rage and disappointment she modeled had been enacted.

“Going cheerfully on with the task”: there’s no doubt that this is admirable, and getting on with things rather than enacting one’s rage may indeed by a truly adult—the only possible—adult response to the complexities of life, including married life. There’s ultimately something a bit stolid about the woman we meet in Flower Diary, though, or about Peacock’s characterization of her anyway, and I think that’s why Flower Diary, interesting as it is, and full as it is of beautiful pictures and wonderful bits of writing, was a disappointment to me after the revelation that was The Paper Garden. The story of Mary Delany discovering and fulfilling her own peculiar creative genius late in life was so exhilarating; it seemed to offer so much hope. It is, as I said in my post about it “a subversive, celebratory view of growing older as a woman”: in Peacock’s wonderful phrasing, “Her whole life flowed to the place where she plucked that moment.”

“Going cheerfully on with the task”: there’s no doubt that this is admirable, and getting on with things rather than enacting one’s rage may indeed by a truly adult—the only possible—adult response to the complexities of life, including married life. There’s ultimately something a bit stolid about the woman we meet in Flower Diary, though, or about Peacock’s characterization of her anyway, and I think that’s why Flower Diary, interesting as it is, and full as it is of beautiful pictures and wonderful bits of writing, was a disappointment to me after the revelation that was The Paper Garden. The story of Mary Delany discovering and fulfilling her own peculiar creative genius late in life was so exhilarating; it seemed to offer so much hope. It is, as I said in my post about it “a subversive, celebratory view of growing older as a woman”: in Peacock’s wonderful phrasing, “Her whole life flowed to the place where she plucked that moment.”

When I wrote about The Paper Garden, it resonated with my rising hope that I too might be finding my moment. Now, almost a decade later, I feel less buoyant, more tired and uncertain. It’s not that I don’t recognize myself in MHR: it’s that I do (except maybe the ability to carry on the endless negotiations between life and work, reality and ambition, as “cheerfully” as she apparently could). Where Mary Delany offered inspiration, Mary Hiester Reid represents something more like sensible resignation: do what you can, keep on doing it as well as you can, be satisfied if the work is good. That’s exactly right, of course, and MHR’s work, as Peacock shows it to me, is good indeed. And yet at the same time it seems uncomfortably apt that the culmination of such a life is a study in greys and not an exuberant flowering.

I am trying. I have read my first new book, now: Lauren Groff’s Matrix. It was a good choice—unusual, unworldly, written in prose direct enough that my wavering concentration wasn’t too much of a problem. I might write a proper post about it in a while. I have been doing some work on my sabbatical project—mostly just reviewing the materials I had gathered and the notes and drafts I had begun last summer, to remind myself how interested and even excited I was about my book idea. I still am, I think: there are flickers, and they feel hopeful, if faint. In between these efforts I watch a lot of TV, a lot of it familiar, some of it new but low-key enough, trivial enough, that I don’t have to risk investing in it emotionally. All of this works to muffle the other thoughts, until it doesn’t. The house is so full of reminders; all I have to do is look up and there are the pictures of his joyful little baby face; there’s the piano he played unlike anyone else, the music just flowing out of his fingers; there’s his old desk; there’s his phone, which I saw so often in his hand. My office on campus is no safer, I realized today, stopping in briefly to grab some books (trying to stoke the embers of my research): more memories, more pictures, the mug he had made for me a few years ago for Christmas.

I am trying. I have read my first new book, now: Lauren Groff’s Matrix. It was a good choice—unusual, unworldly, written in prose direct enough that my wavering concentration wasn’t too much of a problem. I might write a proper post about it in a while. I have been doing some work on my sabbatical project—mostly just reviewing the materials I had gathered and the notes and drafts I had begun last summer, to remind myself how interested and even excited I was about my book idea. I still am, I think: there are flickers, and they feel hopeful, if faint. In between these efforts I watch a lot of TV, a lot of it familiar, some of it new but low-key enough, trivial enough, that I don’t have to risk investing in it emotionally. All of this works to muffle the other thoughts, until it doesn’t. The house is so full of reminders; all I have to do is look up and there are the pictures of his joyful little baby face; there’s the piano he played unlike anyone else, the music just flowing out of his fingers; there’s his old desk; there’s his phone, which I saw so often in his hand. My office on campus is no safer, I realized today, stopping in briefly to grab some books (trying to stoke the embers of my research): more memories, more pictures, the mug he had made for me a few years ago for Christmas.

“Where can we live but days?”

“Where can we live but days?” A lot of people who know about grief have told us it gets better, though it takes time, but also that the process isn’t simple or linear: it isn’t as straightforward as just getting through more days, each of them easier than the last. Right now the passing days feel too fleeting anyway. “I don’t want it to be four days already,” Maddie said last week, and now it has been too many more days but also far from enough days to understand what this loss means for us. We still feel grateful that we know what it meant for Owen, and there is still comfort in his last words of love. But we are the ones who have to go on now, a family of three where once we were four. He couldn’t tell us how to do that any more than we could tell him not to leave us.

A lot of people who know about grief have told us it gets better, though it takes time, but also that the process isn’t simple or linear: it isn’t as straightforward as just getting through more days, each of them easier than the last. Right now the passing days feel too fleeting anyway. “I don’t want it to be four days already,” Maddie said last week, and now it has been too many more days but also far from enough days to understand what this loss means for us. We still feel grateful that we know what it meant for Owen, and there is still comfort in his last words of love. But we are the ones who have to go on now, a family of three where once we were four. He couldn’t tell us how to do that any more than we could tell him not to leave us.

In an era where Mary Cassatt eschewed marriage and a fully adult life to live with her parents in Paris so that she could produce her work, Mary Hiester bounded into an adulthood of painting with a grown-up’s problems of money and sex and logistics . . . Existing with an ambitious man in a socially constricted world for women of which a person today can barely grasp the demeaning dimensions, she lived, by her lights, “cheerfully.” She painted around the obstacles of an artist’s life by employing a woman’s emblem, the rose, and later an emblem of independence, the tree.

In an era where Mary Cassatt eschewed marriage and a fully adult life to live with her parents in Paris so that she could produce her work, Mary Hiester bounded into an adulthood of painting with a grown-up’s problems of money and sex and logistics . . . Existing with an ambitious man in a socially constricted world for women of which a person today can barely grasp the demeaning dimensions, she lived, by her lights, “cheerfully.” She painted around the obstacles of an artist’s life by employing a woman’s emblem, the rose, and later an emblem of independence, the tree. Like Peacock’s earlier, similar work

Like Peacock’s earlier, similar work

Flower Diary follows Mary’s artistic development, integrating it with the story of her personal life—as indeed the two were intricately related in reality. There are lots of parts to both, including the art school Mary and George ran and many trips to Paris and Spain and time spent in an artistic community in Onteora, in the Catskills. Peacock emphasizes Mary’s “persistence” as an artist. Hers was not a bad marriage, or an unsuccessful career: George was a supportive partner, and she was productive and accomplished and recognized. The times were not kind to ambitious women in general, though, or to women artists more particularly. “I don’t know where the assurance and conviction required for Mary’s sort of persistence comes from precisely,” Peacock comments,

Flower Diary follows Mary’s artistic development, integrating it with the story of her personal life—as indeed the two were intricately related in reality. There are lots of parts to both, including the art school Mary and George ran and many trips to Paris and Spain and time spent in an artistic community in Onteora, in the Catskills. Peacock emphasizes Mary’s “persistence” as an artist. Hers was not a bad marriage, or an unsuccessful career: George was a supportive partner, and she was productive and accomplished and recognized. The times were not kind to ambitious women in general, though, or to women artists more particularly. “I don’t know where the assurance and conviction required for Mary’s sort of persistence comes from precisely,” Peacock comments, “Going cheerfully on with the task”: there’s no doubt that this is admirable, and getting on with things rather than enacting one’s rage may indeed by a truly adult—the only possible—adult response to the complexities of life, including married life. There’s ultimately something a bit stolid about the woman we meet in Flower Diary, though, or about Peacock’s characterization of her anyway, and I think that’s why Flower Diary, interesting as it is, and full as it is of beautiful pictures and wonderful bits of writing, was a disappointment to me after the revelation that was The Paper Garden. The story of Mary Delany discovering and fulfilling her own peculiar creative genius late in life was so exhilarating; it seemed to offer so much hope. It is, as I said in my post about it “a subversive, celebratory view of growing older as a woman”: in Peacock’s wonderful phrasing, “Her whole life flowed to the place where she plucked that moment.”

“Going cheerfully on with the task”: there’s no doubt that this is admirable, and getting on with things rather than enacting one’s rage may indeed by a truly adult—the only possible—adult response to the complexities of life, including married life. There’s ultimately something a bit stolid about the woman we meet in Flower Diary, though, or about Peacock’s characterization of her anyway, and I think that’s why Flower Diary, interesting as it is, and full as it is of beautiful pictures and wonderful bits of writing, was a disappointment to me after the revelation that was The Paper Garden. The story of Mary Delany discovering and fulfilling her own peculiar creative genius late in life was so exhilarating; it seemed to offer so much hope. It is, as I said in my post about it “a subversive, celebratory view of growing older as a woman”: in Peacock’s wonderful phrasing, “Her whole life flowed to the place where she plucked that moment.”

Once several years ago I was waiting for my daughter to come out of a medical appointment. The waiting area was, as is typical, neither particularly comfortable nor particularly cheering, and yet when she came out she stopped and exclaimed “you look so happy!” And I was! Why? Because I had just been reading the part of Georgette Heyer’s Devil’s Cub in which (if you know the novel, you can probably already guess) our heroine Mary accidentally tells the forbidding Duke of Avon all about the troubles she has been having with his renegade son, the Marquis of Vidal, with whom she has, against all propriety and practicality, fallen completely in love. I say “accidentally” because she doesn’t know that the enigmatic man she’s talking to is Vidal’s father–but we do, or at least we suspect it much sooner than she discovers it, and so the whole conversation is just delicious, for reasons you have to read the rest of the novel to fully appreciate.

Once several years ago I was waiting for my daughter to come out of a medical appointment. The waiting area was, as is typical, neither particularly comfortable nor particularly cheering, and yet when she came out she stopped and exclaimed “you look so happy!” And I was! Why? Because I had just been reading the part of Georgette Heyer’s Devil’s Cub in which (if you know the novel, you can probably already guess) our heroine Mary accidentally tells the forbidding Duke of Avon all about the troubles she has been having with his renegade son, the Marquis of Vidal, with whom she has, against all propriety and practicality, fallen completely in love. I say “accidentally” because she doesn’t know that the enigmatic man she’s talking to is Vidal’s father–but we do, or at least we suspect it much sooner than she discovers it, and so the whole conversation is just delicious, for reasons you have to read the rest of the novel to fully appreciate. Last week, because the new books I had been reading weren’t thrilling me, I decided to reread an old favorite, Dorothy Dunnett’s The Ringed Castle. I know this novel so well now that sometimes I skim a bit to get to the parts I particularly love. I read quite a bit of it ‘properly’ this time, because it’s just so good, and it helped reconnect me with my inner bookworm. Near the end, there’s a scene in The Ringed Castle that makes me just as happy as that bit of Devil’s Cub (again, readers of the novel can probably guess which one – in fact, when I mentioned this on Twitter

Last week, because the new books I had been reading weren’t thrilling me, I decided to reread an old favorite, Dorothy Dunnett’s The Ringed Castle. I know this novel so well now that sometimes I skim a bit to get to the parts I particularly love. I read quite a bit of it ‘properly’ this time, because it’s just so good, and it helped reconnect me with my inner bookworm. Near the end, there’s a scene in The Ringed Castle that makes me just as happy as that bit of Devil’s Cub (again, readers of the novel can probably guess which one – in fact, when I mentioned this on Twitter  “You look so happy”: that’s not the only thing reading can do, and it isn’t always what we want from our reading, but it’s a special gift when it happens, isn’t it, especially these days? I can think of only a few other scenes that have this particular effect on me: the bathing scene in A Room with a View, the evidence-collecting walk on the beach in Have His Carcase, the rooftop chase in Checkmate (so, score two for Dunnett), the ending of Pride and Prejudice, several small pieces of Cranford (the cow in flannel pyjamas!). Of course there are many, many other reading moments that I love and enjoy and return to over and over, for all sorts of reasons, but these are the some of the ones that make me feel as if I’ve turned my face to the sun: warmed, uplifted, delighted. The joy they give me depends not just on the words on the page but on my history with those pages, and also, as with all idiosyncratic responses, on my own history more generally, and on that elusive thing we could call my “sensibility” as a reader. In that moment everything, not just reading, feels as good as it gets. What a comfort it always is to know that I can return to that happy place any time, just by picking the book up again.

“You look so happy”: that’s not the only thing reading can do, and it isn’t always what we want from our reading, but it’s a special gift when it happens, isn’t it, especially these days? I can think of only a few other scenes that have this particular effect on me: the bathing scene in A Room with a View, the evidence-collecting walk on the beach in Have His Carcase, the rooftop chase in Checkmate (so, score two for Dunnett), the ending of Pride and Prejudice, several small pieces of Cranford (the cow in flannel pyjamas!). Of course there are many, many other reading moments that I love and enjoy and return to over and over, for all sorts of reasons, but these are the some of the ones that make me feel as if I’ve turned my face to the sun: warmed, uplifted, delighted. The joy they give me depends not just on the words on the page but on my history with those pages, and also, as with all idiosyncratic responses, on my own history more generally, and on that elusive thing we could call my “sensibility” as a reader. In that moment everything, not just reading, feels as good as it gets. What a comfort it always is to know that I can return to that happy place any time, just by picking the book up again.

I can’t post about books I’ve finished this week because I haven’t finished any. I’ve been trying to read–keeping in mind

I can’t post about books I’ve finished this week because I haven’t finished any. I’ve been trying to read–keeping in mind  So, one challenge is aging, and there’s not much to be done about that (and it’s only going to get worse, I know!) The other, though, has been the books I’ve been trying to focus on. Both are ones I have wanted to read for a long time, but neither has proved the right book for this moment, although one of them I am still working on. The first one I started this week was Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, which has been on my reading wish list for years. It looks great! I am sure it is great! But a couple of chapters into it, I just couldn’t bear it: it was making me feel both bored and claustrophobic. I suspect some of that is a deliberate effect, as it seems to be about a stifling world that tries to stifle people’s feelings. Bowen’s sentences didn’t help. I love Olivia Manning’s description of Bowen’s prose as being like someone drinking milk with their legs crossed behind their head: often, it just seems to be making something that’s actually fairly simple much more complicated than it needs to be!

So, one challenge is aging, and there’s not much to be done about that (and it’s only going to get worse, I know!) The other, though, has been the books I’ve been trying to focus on. Both are ones I have wanted to read for a long time, but neither has proved the right book for this moment, although one of them I am still working on. The first one I started this week was Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, which has been on my reading wish list for years. It looks great! I am sure it is great! But a couple of chapters into it, I just couldn’t bear it: it was making me feel both bored and claustrophobic. I suspect some of that is a deliberate effect, as it seems to be about a stifling world that tries to stifle people’s feelings. Bowen’s sentences didn’t help. I love Olivia Manning’s description of Bowen’s prose as being like someone drinking milk with their legs crossed behind their head: often, it just seems to be making something that’s actually fairly simple much more complicated than it needs to be!  The other is John Le Carré’s A Perfect Spy, which I am still working on. I loved

The other is John Le Carré’s A Perfect Spy, which I am still working on. I loved  So that’s where I am this week! I have been thinking a lot about posting more in my once-usual “this week in my classes” series but I can’t seem to get past the twin obstacles of my classes

So that’s where I am this week! I have been thinking a lot about posting more in my once-usual “this week in my classes” series but I can’t seem to get past the twin obstacles of my classes

From Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts:

From Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts: