What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

Now, about the books I actually read and wrote about in 2024!

My Year in Reading

When Trevor and Paul once again invited me to share my ‘book of the year’ with them for their year-end episode, it took me no time at all to decide on J. L. Carr’s A Month in the Country. I haven’t had any second thoughts about that choice—it is, as I said to them, pretty much a perfect book. But I think there was some recency bias in my selection: going back through my notes and posts, I see two other books that I loved every bit as much. The first of them, Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, was one of the first books I read in 2024 and I thought it was completely marvelous, so I was thrilled to see it go on to win the Booker Prize. The second, Patrick Bringley’s All the Beauty in the World, is a thoughtful and wide-ranging and sensitive and thought-provoking meditation on art and life: I read it in a library copy, but I keep thinking (after all that talk about pruning and purging!) that I’d like to have my own copy so that I can go back to it whenever I want. I do wish there was a fully illustrated edition—it would have to be very expensive, I suppose, but it would be worth it.

There are another dozen or so titles that stand out to me as particularly rich reading experiences. My blogging was a bit fitful in 2024, but usually when a book really excited me (for better or for worse) it got its own post, instead of being included in a hastier round-up, so it wouldn’t be hard to find out which ones they were by just scrolling back through my year’s posts! But I will highlight a few. One absolute delight, which I did not in fact write up individually (but I read it in February, the month I actually moved, so it’s amazing that I wrote anything at all!) was Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard. I can’t recommend this book highly enough. Its premise is so simple (it’s about a man who falls overboard—surprise!) but between his thoughts as he tries to stay afloat and the reactions of those left behind on the ship, the little episode takes on real philosophical, even existential, weight without every becoming ponderous. Another book, in a completely different style, that also takes on Big Issues is Joan Barfoot’s Exit Lines, a darkly comic novel about what makes life worth living, and who has the right to decide what those reasons have run out. Sarah Perry’s Enlightenment, which I reviewed for the TLS, also takes into questions about the meaning of life, but with such delicacy and tenderness; it is my favorite of Perry’s novels to date (although if your tastes are more Gothic, I highly recommend Melmoth, which I thoroughly enjoyed). I suppose it stands to reason that someone whose favorite novelist overall is George Eliot would appreciate novels with a philosophical dimension. The challenge, as Eliot herself noted, is never to “lapse from the picture to the diagram,” and I think each of these novels in its own way invites us to contemplate important questions without becoming programmatic.

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (which did). Bostridge’s book is actually a hybrid of biography and autobiography. It is mostly about the sad life of Adele Hugo, Victor Hugo’s younger daughter, who broke away from her father’s overbearing presence and confining household to follow the soldier she’d fallen in love with all the way to Halifax and then to Jamaica. Unfortunately, he was not in love with her, which makes the whole saga both more dramatic—imagine the daring it took, in the mid 19th century, for a young woman to cross the oceans to get what she wanted—and more tragic. Bostridge weaves into this reflections on his own relationship with his father and his own pursuits of love. It’s a compelling narrative on both counts, and the local colour added to its interest, as Bostridge retraced Adele’s journey to Halifax and explored her haunts here (and had dinner with me, incidentally).

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (which did). Bostridge’s book is actually a hybrid of biography and autobiography. It is mostly about the sad life of Adele Hugo, Victor Hugo’s younger daughter, who broke away from her father’s overbearing presence and confining household to follow the soldier she’d fallen in love with all the way to Halifax and then to Jamaica. Unfortunately, he was not in love with her, which makes the whole saga both more dramatic—imagine the daring it took, in the mid 19th century, for a young woman to cross the oceans to get what she wanted—and more tragic. Bostridge weaves into this reflections on his own relationship with his father and his own pursuits of love. It’s a compelling narrative on both counts, and the local colour added to its interest, as Bostridge retraced Adele’s journey to Halifax and explored her haunts here (and had dinner with me, incidentally).

Ann Schlee’s Rhine Journey has been highlighted by many others in their ‘best of’ lists; I was very impressed by it too, as I was by Dorothy Baker’s Cassandra at the Wedding. Neither of these is exactly a feel-good read! Another book that has consistently had a lot of buzz in my reading circles is Dorothy B. Hughes’s The Expendable Man; I finally read it and yes, it is indeed excellent. I think I consider In a Lonely Place a slightly better novel (more subtle, more artful) but The Expendable Man is so clever and does such important things within its noir-ish form that I couldn’t resist adding it to the reading list for my Mystery & Detective Fiction class this coming term. I was not so enthralled by Claudia Piñeiro’s Time of the Flies, which was the least intelligible and satisfying of her novels for me so far. I got a lot out of reading and thinking about Denise Mina’s The Long Drop, but I’m still not entirely on board with true crime as a genre—although, perhaps inconsistently, I am not  bothered by historical true crime, and along those lines I quite enjoyed my King’s colleague Dean Jobb’s A Gentleman and a Thief, about the jazz-age jewel thief Arthur Barry.

bothered by historical true crime, and along those lines I quite enjoyed my King’s colleague Dean Jobb’s A Gentleman and a Thief, about the jazz-age jewel thief Arthur Barry.

In lighter reading, I loved David Nicholls’s You Are Here—he seems to be a really reliable sort of writer, one whose fiction is accessible without being hasty or flimsy. I still think often about Us, which I read well before my own separation, not because its protagonists are like my own family at all, but because it shows them grappling with changing needs, and just with change, in really perceptive but not melodramatic ways. I discovered (belatedly!) Katherine Center and found much to enjoy in her intelligent romances; I read several of Abby Jimenez’s novels and then decided I’d had enough.

My book club got on a French kick that began with Diane Johnson and took us through de Maupassant, Colette, and Dumas (fils). (I also read Zola’s La Bête Humaine—the One Bright Book people made me do it! Ok, they didn’t make me, but I was inspired to read it so I could properly appreciate their episode. The novel is . . . a lot! And Sarah Turnbull’s astute and lively Almost French was an unanticipated connection between these French books and the other memoirs I read.) We chose Elizabeth von Arnim’s Vera for our last book of the year and it is another I highly recommend, especially if you read and liked Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Vera has a lot in common with Rebecca—the whole plot, really—but the tone is quite different, darker, I would say, because the shadows in Rebecca are Gothic ones and so can be shaken off more easily than the more chillingly realistic menace von Arnim offers up.

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be Noémi Kiss-Deáki’s Mary and the Rabbit Dream, though I’m a bit reluctant to characterize it that way. There is so much that’s interesting about it, and its style (while off-putting to me) does have an idiosyncratic kind of freshness to it: it doesn’t sound like any other book I’ve read, not just in 2024 but maybe ever! Was the author being innovative, taking an artistic risk in writing it this way? or is she just not a very good writer? If you read it, I’d be interested to know what you decided!

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be Noémi Kiss-Deáki’s Mary and the Rabbit Dream, though I’m a bit reluctant to characterize it that way. There is so much that’s interesting about it, and its style (while off-putting to me) does have an idiosyncratic kind of freshness to it: it doesn’t sound like any other book I’ve read, not just in 2024 but maybe ever! Was the author being innovative, taking an artistic risk in writing it this way? or is she just not a very good writer? If you read it, I’d be interested to know what you decided!

These are not all the books I read in 2024, of course, but they’re the ones that stand out when I look over my notes and posts. One other change in my book habits seems worth mentioning: I experimented quite a bit with audiobooks this year, partly because of all those extra hours I’ve found in the day, which have meant more time on things like crafts and puzzles. In the past I have not had much success with listening to books, but some of them were great. I would especially highlight Dan Stevens’s wonderful reading of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None; Naomi Klein’s reading of her own (exceptionally thought-provoking) Doppelganger, which is really worth reading (or listening to) as we head into the second (sigh) Trump presidency; and David Grann’s The Wager, read by Dion Graham, which kept me spellbound.

My Year in Writing

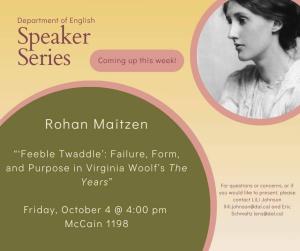

I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s The Gift Child, Jenny Haysom’s Keep, and Ayelet Tsabari’s Songs for the Brokenhearted. And I did my second review for the Literary Review of Canada, this time of Tammy Armstrong’s Pearly Everlasting, about a girl whose brother is a bear. (What is it with CanLit and bears?) I worked quite a bit on my “project” (I hate that word, but what else is there?) on Woolf’s The Years as a failed ‘novel of purpose’; I kept myself motivated by putting myself on the list for our department’s Speaker Series. I think the presentation went fine. As always, the tough questions I anticipated and fretted about greatly beforehand were not the ones asked, and in fact I really enjoyed the Q&A.

I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s The Gift Child, Jenny Haysom’s Keep, and Ayelet Tsabari’s Songs for the Brokenhearted. And I did my second review for the Literary Review of Canada, this time of Tammy Armstrong’s Pearly Everlasting, about a girl whose brother is a bear. (What is it with CanLit and bears?) I worked quite a bit on my “project” (I hate that word, but what else is there?) on Woolf’s The Years as a failed ‘novel of purpose’; I kept myself motivated by putting myself on the list for our department’s Speaker Series. I think the presentation went fine. As always, the tough questions I anticipated and fretted about greatly beforehand were not the ones asked, and in fact I really enjoyed the Q&A.

As we head into 2025, I am thinking about how to “level up” a bit in my writing. I do really like doing reviews that have a limited scope, which I find creatively and intellectually challenging (what can I do in just 700 words?), and also comfortable, in their specificity. But I used to sometimes publish more essayistic pieces too, and I want to give some thought to what else I might do along those lines. I also don’t want all that Woolf work to stop with the presentation version, but at the same time I find it very hard to feel motivated to turn it into an academic article, even though that was my initial plan. I think I need to crack it open and reconsider it as something that might (might!) work for the kind of venue I used to dream of getting into—and did, unsuccessfully, submit to a couple of times—in the past, something like the Hudson Review, maybe. A writer’s reach must exceed her grasp, right?

My previous, somewhat paradoxical, experience has been that writing more means I write more—when I kept up my blog more faithfully, for example, I published a lot more other writing as well. Of course, a lot of other things were different in the past, and I don’t know if 2025 will be the year I get my momentum back. I hope I at least try, because I don’t feel altogether satisfied with my recent output, which is not about “productivity” but more about the kinds of things we were talking about in a more tangible context in the comments on my previous post: what matters, what lasts, what remains.

And on that note—is it sobering or uplifting, aspirational or anxious? all of the above!—I think that’s a wrap on this year-end review. It’s hard to imagine that 2025 can be even a fraction as tumultuous as any of the past three years, personally at any rate (politically, on both sides of the border, it seems likely to be a big old mess). Whatever happens, at least there will always be books, right?

That instant, the memory of a long-lost word rises up in her, cut in half, and she tries to grab hold of it. She had learned that, in times past, there had been a word, a Hanja word . . . by which people had referred to the half-light just after the sun sets and just before it rises. A word that means having to call out in a loud voice, as the person approaching from a distance is too far away to be recognized, to ask who they are . . . This eternally incomplete, eternally unwhole word stirs deep within her, never reaching her throat.

That instant, the memory of a long-lost word rises up in her, cut in half, and she tries to grab hold of it. She had learned that, in times past, there had been a word, a Hanja word . . . by which people had referred to the half-light just after the sun sets and just before it rises. A word that means having to call out in a loud voice, as the person approaching from a distance is too far away to be recognized, to ask who they are . . . This eternally incomplete, eternally unwhole word stirs deep within her, never reaching her throat. And yet overall I was captivated by Greek Lessons, not so much by its particulars as by the melancholy space it created. Ordinarily I prefer some forward momentum in a novel (both cause and effect of my specializing in the 19th-century novel for so long!). What Greek Lessons offers instead, or this is how it felt to me, is a kind of time out, from that fictional drive and also from the busy world that these days overwhelms us with “content” and noise. In the intimacy of the portrayal of these two people, both of whom are retreating from the world partly by choice but mostly from the cruelty of their circumstances, there is some recognition of how hard it is to be ourselves, to be authentic, to see each other. The quiet sparseness of Han Kang’s writing could be seen as an antidote to the pressure to perform who we are and to insist on making space for ourselves out there. (Pressured by her therapist to break her silence, the woman thinks, “she still did not wish to take up more space.”)

And yet overall I was captivated by Greek Lessons, not so much by its particulars as by the melancholy space it created. Ordinarily I prefer some forward momentum in a novel (both cause and effect of my specializing in the 19th-century novel for so long!). What Greek Lessons offers instead, or this is how it felt to me, is a kind of time out, from that fictional drive and also from the busy world that these days overwhelms us with “content” and noise. In the intimacy of the portrayal of these two people, both of whom are retreating from the world partly by choice but mostly from the cruelty of their circumstances, there is some recognition of how hard it is to be ourselves, to be authentic, to see each other. The quiet sparseness of Han Kang’s writing could be seen as an antidote to the pressure to perform who we are and to insist on making space for ourselves out there. (Pressured by her therapist to break her silence, the woman thinks, “she still did not wish to take up more space.”) November wasn’t a bad reading month, considering how busy things were at work—and considering that “work” also means reading a fair amount, this time around including most of both Lady Audley’s Secret and Tess of the d’Urbervilles for 19thC Fiction and an array of short fiction and poetry for my intro class. (I have not managed to get back into a routine of posting about my teaching, but I would like to, so we’ll see what happens next term.)

November wasn’t a bad reading month, considering how busy things were at work—and considering that “work” also means reading a fair amount, this time around including most of both Lady Audley’s Secret and Tess of the d’Urbervilles for 19thC Fiction and an array of short fiction and poetry for my intro class. (I have not managed to get back into a routine of posting about my teaching, but I would like to, so we’ll see what happens next term.)

I felt the need for something cheering in the wake of The Election and landed on Connie Willis’s To Say Nothing of the Dog: it was a great choice, genuinely comic and warm-hearted but also endlessly clever. I had a lot of LOL moments over its characterizations of the Victorian period, and it is chock full of literary allusions, many of which I’m sure I didn’t catch. A lot of them are to Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers: who know that Gaudy Night would be one of its main running references. I liked it enough that I’ve put The Doomsday Book on my Christmas wish list, even though I don’t ordinarily gravitate towards this genre.

I felt the need for something cheering in the wake of The Election and landed on Connie Willis’s To Say Nothing of the Dog: it was a great choice, genuinely comic and warm-hearted but also endlessly clever. I had a lot of LOL moments over its characterizations of the Victorian period, and it is chock full of literary allusions, many of which I’m sure I didn’t catch. A lot of them are to Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers: who know that Gaudy Night would be one of its main running references. I liked it enough that I’ve put The Doomsday Book on my Christmas wish list, even though I don’t ordinarily gravitate towards this genre. Claudia Piñeiro’s Time of the Flies is, like the other novels of hers that I’ve read, a crime novel. Sort of. It is about a convicted murderer, Inés: she killed her husband’s lover, but at the time of the novel is out of prison and making her living running an environmentally friendly pest control business. Then she is approached by one of her clients to provide a deadly pesticide—so that she too can kill “a woman who wants to take my husband the same way yours was taken from you,” or so she tells Inés. Inés, who is not in general a murderous person and who also would very much like not to go back to prison, is tempted only because her friend Manca urgently needs treatment for breast cancer but can’t afford to pay to get it right away. The situation gets more complicated when a connection emerges between the client and the daughter Inés has not seen since her imprisonment.

Claudia Piñeiro’s Time of the Flies is, like the other novels of hers that I’ve read, a crime novel. Sort of. It is about a convicted murderer, Inés: she killed her husband’s lover, but at the time of the novel is out of prison and making her living running an environmentally friendly pest control business. Then she is approached by one of her clients to provide a deadly pesticide—so that she too can kill “a woman who wants to take my husband the same way yours was taken from you,” or so she tells Inés. Inés, who is not in general a murderous person and who also would very much like not to go back to prison, is tempted only because her friend Manca urgently needs treatment for breast cancer but can’t afford to pay to get it right away. The situation gets more complicated when a connection emerges between the client and the daughter Inés has not seen since her imprisonment.

That might be a good explanation for the hybrid nature of Time of the Flies, but it doesn’t necessarily make the book a success. I’d probably have to read it again (and again) to make up my mind about that, which I might do, given that I offer a course called “Women and Detective Fiction.” Last time around I almost assigned Elena Knows for it. Another title I’ve considered for the book list is Jo Baker’s The Body Lies, which is quite unlike Time of the Flies except that it too is a crime novel that turns out to be about crime novels, and especially about the roles and depiction of women in them, the voyeurism of violence against women, the prurient fixation on their wounded or dead bodies, the genre variations that both do and don’t reconfigure women’s relationship to the stories we tell about crime and violence. I thought Baker’s novel was excellent. I certainly didn’t have any trouble finishing it, in contrast to the concerted effort I made to get to the end of Time of the Flies. I really did want to know what happened! But I felt like I had to wade through a lot of other stuff to get there. If I do reread it, maybe that stuff will turn out to be the real substance of the book.

That might be a good explanation for the hybrid nature of Time of the Flies, but it doesn’t necessarily make the book a success. I’d probably have to read it again (and again) to make up my mind about that, which I might do, given that I offer a course called “Women and Detective Fiction.” Last time around I almost assigned Elena Knows for it. Another title I’ve considered for the book list is Jo Baker’s The Body Lies, which is quite unlike Time of the Flies except that it too is a crime novel that turns out to be about crime novels, and especially about the roles and depiction of women in them, the voyeurism of violence against women, the prurient fixation on their wounded or dead bodies, the genre variations that both do and don’t reconfigure women’s relationship to the stories we tell about crime and violence. I thought Baker’s novel was excellent. I certainly didn’t have any trouble finishing it, in contrast to the concerted effort I made to get to the end of Time of the Flies. I really did want to know what happened! But I felt like I had to wade through a lot of other stuff to get there. If I do reread it, maybe that stuff will turn out to be the real substance of the book.