How I hate the word “relatable,” which is so often a shorthand for “like me and thus likeable,” which in turn is both a shallow standard for merit and a lazy way to react to a character. And yet sometimes it’s irresistible as a way to capture the surprise of finding out that someone who otherwise seems so different, elusive, iconic, really can be in some small way just like me—a writer of genius, for example, who reacts to invitations by worrying that she has nothing nice to wear and doesn’t look very good in what she does have. Yes, the period of Woolf’s diary I am reading is one of great intellectual and artistic flourishing, and this makes it all the more touching as well as oddly endearing that she frets so much about “powder & paint, shoes & stockings.” “My own lack of beauty depresses me today,” she writes on March 3, 1926;

How I hate the word “relatable,” which is so often a shorthand for “like me and thus likeable,” which in turn is both a shallow standard for merit and a lazy way to react to a character. And yet sometimes it’s irresistible as a way to capture the surprise of finding out that someone who otherwise seems so different, elusive, iconic, really can be in some small way just like me—a writer of genius, for example, who reacts to invitations by worrying that she has nothing nice to wear and doesn’t look very good in what she does have. Yes, the period of Woolf’s diary I am reading is one of great intellectual and artistic flourishing, and this makes it all the more touching as well as oddly endearing that she frets so much about “powder & paint, shoes & stockings.” “My own lack of beauty depresses me today,” she writes on March 3, 1926;

But how far does the old convention about ‘beauty’ bear looking into? I think of the people I have known. Are they beautiful? This problem I leave unsolved.

On March 20 she remarks “a slight melancholia,”

which comes upon me sometimes now, & makes me think I am old: I am ugly. I am repeating things. Yet, as far as I know, as a writer I am only now writing out my mind.

She loves socializing, thrives on conversation, but dreads dressing up for it: “When I am asked out,” she notes in May, “my first thought is, but I have no clothes to go in.” She undertakes to go to “a dressmaker recommended by Todd [the editor of Vogue]”: “I tremble & shiver all over at the appalling magnitude of the task I have undertaken.” Happily, it goes well:

I went to my dressmaker, Miss Brooke, & found it the most quiet & friendly and even enjoyable of proceedings. I have a great lust for lovely stuffs, & shapes . . . A bold move, this, but now I’m free of the fret of clothes, which is worth paying for, & need not parade Oxford Street.

No sooner is she feeling more at ease, even easy, about how she looks, then stupid Clive Bell has to go and ruin everything:

No sooner is she feeling more at ease, even easy, about how she looks, then stupid Clive Bell has to go and ruin everything:

This is the last day of June [1926] & finds me in black despair because Clive laughed at my new hat, Vita pitied me, & I sank to the depths of gloom. This happened at Clive’s last night after going to the Sitwell’s with Vita. Oh dear I was wearing the hat without thinking whether it was good or bad; & it was all very flashing and easy . . . Come on all of us to Clive’s, I said; & they agreed. Well, it was after they had come & we were all sitting round talking that Clive suddenly said, or bawled rather, what an astonishing hat you’re wearing! Then he asked where I got it. I pretended a mystery, tried to change the talk, was not allowed, & they pulled me down between them like a hare; I never felt more humiliated. Clive said did Mary choose it? No. Todd said Vita. And the dress? Todd of course. After that I was forced to go on as if nothing terrible had happened; but it was very forced & queer & humiliating. So I talked & laughed too much, Duncan prim & acid as ever told me it was utterly impossible to do anything with a hat like that. And I joked about the Squires’ party & Leonard got silent, & I came away deeply chagrined, as unhappy as I have been these ten years; & revolved it in sleep & dreams all night; & today has been ruined.

Thanks a lot, Clive! And you too, Duncan: I bet your hats were all plenty stupid-looking! But seriously, although at the time Woolf really was not “old” (and it is hard for me to think of her as anything but strikingly beautiful), isn’t it hard enough going out in public in this sexist and judgmental world as an aging woman who knows her strengths lie somewhere other than in her looks, without our dearest friends making us wish we’d stayed home?

(I don’t think either of the hats in the photos here is the hat! They are both great hats, but neither of them, surely, is astonishing.)

But this slight depression—what is it? I think I could cure it by crossing the channel, & writing nothing for a week . . . But oh the delicacy & complexity of the soul—for, haven’t I begun to tap her & listen to her breathing after all? A change of house makes me oscillate for days. And thats [sic] life; thats wholesome. Never to quiver is the lot of Mr. Allinson, Mrs. Hawkesford, & Jack Squire. In two or three days, acclimatised, started, reading & writing, no more of this will exist. And if we didn’t live venturously, plucking the wild goat by the beard, & trembling over precipices, we should never be depressed, I’ve no doubt, but already should be faded, fatalistic & aged.

But this slight depression—what is it? I think I could cure it by crossing the channel, & writing nothing for a week . . . But oh the delicacy & complexity of the soul—for, haven’t I begun to tap her & listen to her breathing after all? A change of house makes me oscillate for days. And thats [sic] life; thats wholesome. Never to quiver is the lot of Mr. Allinson, Mrs. Hawkesford, & Jack Squire. In two or three days, acclimatised, started, reading & writing, no more of this will exist. And if we didn’t live venturously, plucking the wild goat by the beard, & trembling over precipices, we should never be depressed, I’ve no doubt, but already should be faded, fatalistic & aged. Winifred Holtby’s chapter on this period of Woolf’s life is called “The Adventure Justified”: “she was more sure now,” Holtby writes, “both of herself and of her public. She dared take greater risks with them, confident that they would not let her down.” It’s a wonderful chapter, rising almost to ecstasy about Woolf’s achievement in To the Lighthouse:

Winifred Holtby’s chapter on this period of Woolf’s life is called “The Adventure Justified”: “she was more sure now,” Holtby writes, “both of herself and of her public. She dared take greater risks with them, confident that they would not let her down.” It’s a wonderful chapter, rising almost to ecstasy about Woolf’s achievement in To the Lighthouse: In my previous post I wondered whether we knew what Woolf’s wishes were for her diary: whether she imagined it as something others would someday read, or thought of it as—and hoped it would remain—a private space. How might these different ideas about what she was writing, or who she was writing for, have affected what she wrote? With these questions still lingering as I read on yesterday, I reached an entry that explicitly addresses what keeping a diary meant to her and what her aspirations were for it, particularly for herself as a writer. It’s a longish passage but I’m going to copy the whole of it here, because I find every bit of it so interesting. It’s part of her entry for Sunday 20 April, 1919.

In my previous post I wondered whether we knew what Woolf’s wishes were for her diary: whether she imagined it as something others would someday read, or thought of it as—and hoped it would remain—a private space. How might these different ideas about what she was writing, or who she was writing for, have affected what she wrote? With these questions still lingering as I read on yesterday, I reached an entry that explicitly addresses what keeping a diary meant to her and what her aspirations were for it, particularly for herself as a writer. It’s a longish passage but I’m going to copy the whole of it here, because I find every bit of it so interesting. It’s part of her entry for Sunday 20 April, 1919. I love that.

I love that. At first I was thinking that not much was really happening in this section, but then it struck me that of course there is a war on, as we are reminded by several passing references to German prisoners working on the nearby farms: “To picnic near Firle,” she reports on August 11, for example, “with Bells &c. Passed German prisoners, cutting wheat with hooks.” Also during this period Leonard is called up to military service, and their efforts to have him excused on medical grounds are repeatedly mentioned. Once they are back at Richmond, they are constantly on edge about air raids: on December 6, she is “wakened by L. to a most instant sense of guns: as if one’s faculties jumped up fully dressed.” They retreat to the kitchen passage then go back to bed when the danger seems passed, only to be once again roused by “guns apparently at Kew.” The raid, the papers tell her the next day, “was the work of 25 Gothas, attacking in 5 squadrons, and 2 were brought down.”

At first I was thinking that not much was really happening in this section, but then it struck me that of course there is a war on, as we are reminded by several passing references to German prisoners working on the nearby farms: “To picnic near Firle,” she reports on August 11, for example, “with Bells &c. Passed German prisoners, cutting wheat with hooks.” Also during this period Leonard is called up to military service, and their efforts to have him excused on medical grounds are repeatedly mentioned. Once they are back at Richmond, they are constantly on edge about air raids: on December 6, she is “wakened by L. to a most instant sense of guns: as if one’s faculties jumped up fully dressed.” They retreat to the kitchen passage then go back to bed when the danger seems passed, only to be once again roused by “guns apparently at Kew.” The raid, the papers tell her the next day, “was the work of 25 Gothas, attacking in 5 squadrons, and 2 were brought down.”

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937)

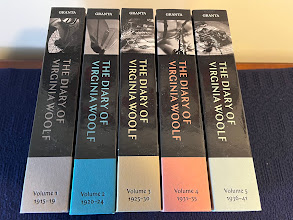

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937) With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

Where Mrs. Browning saw, he smelt; where she wrote, he snuffed.

Where Mrs. Browning saw, he smelt; where she wrote, he snuffed. And this brings me to the other thing I really liked about Flush, which is the clever way Woolf conveys the daring and intensity of the romance between EBB and Robert Browning. Flush is keenly sensitive to changes in his mistress’s mood and the progress of her feelings for Browning – from keen but uncertain interest to expanding confidence to love – is beautifully conveyed through Flush’s peripheral and often peevish point of view:

And this brings me to the other thing I really liked about Flush, which is the clever way Woolf conveys the daring and intensity of the romance between EBB and Robert Browning. Flush is keenly sensitive to changes in his mistress’s mood and the progress of her feelings for Browning – from keen but uncertain interest to expanding confidence to love – is beautifully conveyed through Flush’s peripheral and often peevish point of view:

This is not to say that there is nothing original about Square Haunting; Wade has not just done her homework and synthesized her findings but added details and insights of her own. Still, the most original thing about her book is its concept: grouping these five women together because they (more or less) shared an address. Wade makes the most of this geographical link, discussing the history of Bloomsbury in general and Mecklenburgh Square more specifically to clarify what it meant to choose to live there, especially for women moving away–as all her subjects were–from women’s conventional roles and paths. Having rooms of their own was both a vital practical step towards the independence they wanted and a heavily symbolic one, a point Wade makes (inevitably and rightly) with plenty of allusions to Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own.

This is not to say that there is nothing original about Square Haunting; Wade has not just done her homework and synthesized her findings but added details and insights of her own. Still, the most original thing about her book is its concept: grouping these five women together because they (more or less) shared an address. Wade makes the most of this geographical link, discussing the history of Bloomsbury in general and Mecklenburgh Square more specifically to clarify what it meant to choose to live there, especially for women moving away–as all her subjects were–from women’s conventional roles and paths. Having rooms of their own was both a vital practical step towards the independence they wanted and a heavily symbolic one, a point Wade makes (inevitably and rightly) with plenty of allusions to Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own.