![]()

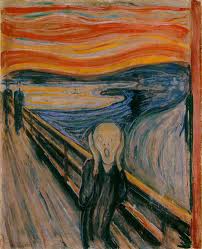

The second half of term, and especially the couple of weeks right after our November reading week (which falls uncomfortably late in the term, as I’ve often complained), always go by in a mad rush. This term has been no different in that respect, except that the mad rush has just been more of the exact same things I’ve been doing since September: staring at the screen, typing, clicking, staring some more, typing, clicking. Because we have the same routines on Saturdays and Sundays as on every other days of the week, too, it really all just blurs into one long sameness, one continuous stretch of staring and typing and clicking, with just our daily walks, our meals, and our evening television as interruptions and diversions.

It hasn’t been all bad, though. I said back in October that given the choice, I’d never teach all online again, and that remains true. But would I never teach online again at all, ever, if it were up to me? I can actually imagine, now, that there might be circumstances in which I would appreciate some features of online teaching, especially if the rest of my life were restored. I don’t miss early morning starts, and once wintry weather arrives I will be glad not to be forced out into it. If I had to – or chose to – be somewhere else for a while, I wouldn’t be so constrained by the implacability of the academic calendar. And it’s not all new to me any more: though I don’t love Brightspace, I know my way around it a lot better than I did in May, for one thing, and when I recorded my concluding lectures for my courses I felt much more comfortable and confident in front of the camera than I did when I made my first videos in August.

It hasn’t been all bad, though. I said back in October that given the choice, I’d never teach all online again, and that remains true. But would I never teach online again at all, ever, if it were up to me? I can actually imagine, now, that there might be circumstances in which I would appreciate some features of online teaching, especially if the rest of my life were restored. I don’t miss early morning starts, and once wintry weather arrives I will be glad not to be forced out into it. If I had to – or chose to – be somewhere else for a while, I wouldn’t be so constrained by the implacability of the academic calendar. And it’s not all new to me any more: though I don’t love Brightspace, I know my way around it a lot better than I did in May, for one thing, and when I recorded my concluding lectures for my courses I felt much more comfortable and confident in front of the camera than I did when I made my first videos in August.

Over the last week or so, in the lull between the incessant weekly tasks of this term’s classes and the arrival of their final essays and exams, I have been finalizing the syllabi and working on the course sites for next term’s classes, and while I certainly don’t think I have got this whole thing figured out, I do feel as if I’ve learned a lot by doing it once that will help me do it better. Right now it seems about 50/50 that we’ll be going back to in-person teaching in Fall 2021: with the roll-out of vaccines beginning even as I write this, it isn’t impossible that by then enough of us will be protected that some semblance of normalcy will have returned, though we are still in such uncharted territory that it would be foolish to assume anything about the future. I would still rather teach online than be back in a classroom hamstrung by necessary safety measures and shadowed by anxiety. Maybe even once classroom teaching is securely the default once again, there will still be times when I will be glad to have acquired this experience and to know that I can do it again if I have to or want to.

So what have I learned? In addition to the technical stuff – Brightspace and Panopto and Collaborate, oh my! – I have learned, as a lot of other people have too, that the best advice and methods for online teaching may not be the best advice and methods for online teaching in these circumstances. “Formative” assessments, scaffolded assignments, regular low-stakes engagement exercises: they may all be (and in fact I believe they are) pedagogically effective, but when we all start doing them all at once with students many of whom are used to more episodic kinds of engagement (essay assignments, midterms, final projects, etc.), the overall effect is overwhelming. I spent a lot of time puzzling over exactly the issue addressed in that linked essay: in my mind, as I planned my courses, if anything I was requiring much less work than usual, as I’d cut back the reading assignments and instead of three class meetings a week students had “just” a couple of short videos to watch and some informal writing to do, plus the usual papers and tests.

So what have I learned? In addition to the technical stuff – Brightspace and Panopto and Collaborate, oh my! – I have learned, as a lot of other people have too, that the best advice and methods for online teaching may not be the best advice and methods for online teaching in these circumstances. “Formative” assessments, scaffolded assignments, regular low-stakes engagement exercises: they may all be (and in fact I believe they are) pedagogically effective, but when we all start doing them all at once with students many of whom are used to more episodic kinds of engagement (essay assignments, midterms, final projects, etc.), the overall effect is overwhelming. I spent a lot of time puzzling over exactly the issue addressed in that linked essay: in my mind, as I planned my courses, if anything I was requiring much less work than usual, as I’d cut back the reading assignments and instead of three class meetings a week students had “just” a couple of short videos to watch and some informal writing to do, plus the usual papers and tests.

What I think I had miscalculated, however, is how little specific accountability there really was in most of those classroom hours: students could do all the reading and come prepared to discuss it, and some certainly did, but others didn’t, or didn’t always, and they could count on that time as useful but passive, a chance to listen in on what the rest of us had to say without having to generate material of their own. The new expectation that they “show up” in writing seemed like a great opportunity to make sure the talkative portion of the class wasn’t the only part that I heard from, and that was a good aspect of it. Even for the students who typically did the readings and did want to talk about them, though, the written alternatives felt harder, I think, and created more pressure, no matter how hard I tried to explain that they were meant to be low key, not high stakes. Plus, again, if every class is asking for a constant stream of input, the logistics alone probably get bewildering.

That said, I’m still going to ask for online discussions in my winter term courses! Expressing your ideas about what you’ve read in words is the fundamental task and method of literary studies, after all. I lessened the requirements in one of my classes this term, once we started to hear reports of students being overwhelmed, and for next term I have (I think!) made the requirements more streamlined, and also explained better what the terms and expectations are. In retrospect I should perhaps have scaled things back in my first-year course, where I was (still am!) doing my first experiment with specifications grading – but I honestly didn’t expect that so many of them would fix on and stay fixed on fulfilling the most demanding bundle. I expected a much larger number to decide that level of effort was a bit much just to cross off their writing requirement: instead, knowing it was achievable with enough persistence seems to have motivated a significant portion of the class to do a lot of regular writing. They will have worked very hard on a whole range of tasks, so I certainly don’t begrudge them their As, though this is something I will think more about when (if) I do specifications grading again – which will have to be the subject of its own post when the term is really and truly over and I have a more complete sense of whether or how the experiment succeeded or failed.

That said, I’m still going to ask for online discussions in my winter term courses! Expressing your ideas about what you’ve read in words is the fundamental task and method of literary studies, after all. I lessened the requirements in one of my classes this term, once we started to hear reports of students being overwhelmed, and for next term I have (I think!) made the requirements more streamlined, and also explained better what the terms and expectations are. In retrospect I should perhaps have scaled things back in my first-year course, where I was (still am!) doing my first experiment with specifications grading – but I honestly didn’t expect that so many of them would fix on and stay fixed on fulfilling the most demanding bundle. I expected a much larger number to decide that level of effort was a bit much just to cross off their writing requirement: instead, knowing it was achievable with enough persistence seems to have motivated a significant portion of the class to do a lot of regular writing. They will have worked very hard on a whole range of tasks, so I certainly don’t begrudge them their As, though this is something I will think more about when (if) I do specifications grading again – which will have to be the subject of its own post when the term is really and truly over and I have a more complete sense of whether or how the experiment succeeded or failed.

Once again I seem to be focused in this teaching post primarily on logistics and methods rather than on the content of my courses: this has been my lament all term, really, because compared with just showing up to class with my book and my notes, offering an online lesson or module is just a whole lot more complicated. Reviewing my recorded lectures as I made up review handouts and final exams, though, I was pleased to see that they are pretty substantial. Within the relatively simple options I chose to deliver them (basically, just narrated PowerPoints, pretty much all under 15 minutes each) they are as interesting and creative as I could manage; thinking of ways to present ideas in this format, especially ideas derived from or modeling close reading, was conceptually challenging. That was my favorite part of each week’s class prep, and I’m actually kind of looking forward to doing more of it next term, especially because I’ll be working with readings that I know really well, which makes the jump from “what’s next?” to “what do I want to say about it?” much easier.

This term isn’t over yet, though: starting tomorrow I’ll be deep in exams and essays, which is at least par for the course, for this point in the year. Despite the monotonous way one day has blurred into the next, and the difficulty of keeping my spirits up in this surreal, isolated, scary time, I’ve been grateful that my work has continued and has kept me so busy that I can marvel that it’s “already” December. I expect that next term will be much the same – and maybe by the time I look up from my screen and marvel that it’s “already” April the tentative optimism sparked by today’s good news will have turned into genuine hope for the future.

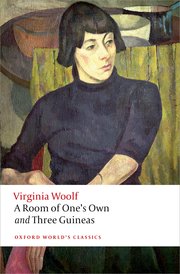

If you’d asked me on March 13 of this year (the last “regular” day before we were all locked down!) whether I ordinarily spent a lot of time working at my computer, I would have said “Yes!” without hesitation. It turns out, however, that I used to greatly underestimate the amount of time I spent away from my computer–at least, relative to the balance (or, rather, imbalance) between these two options in my pandemic life. While preparing for class always involved at least some time typing up notes and preparing handouts, worksheets, slides, and other materials, for example, going to class meant gathering up actual books and papers and markers–and sometimes

If you’d asked me on March 13 of this year (the last “regular” day before we were all locked down!) whether I ordinarily spent a lot of time working at my computer, I would have said “Yes!” without hesitation. It turns out, however, that I used to greatly underestimate the amount of time I spent away from my computer–at least, relative to the balance (or, rather, imbalance) between these two options in my pandemic life. While preparing for class always involved at least some time typing up notes and preparing handouts, worksheets, slides, and other materials, for example, going to class meant gathering up actual books and papers and markers–and sometimes But here I am now, ready once again to take stock of how things are going in my classes. And the disconcerting truth is that a third of the way through this strange term, I still don’t really know, because I have no base line for comparison, no past experience to check this one against. I’m working pretty incessantly on one teaching task or another, but I get very little feedback compared to the ongoing opportunity, in face-to-face teaching, to “read the room”–which could, of course, be discouraging if you could tell they weren’t with you, but at least there was some immediacy to that input and enough flexibility to the whole operation to let you change things up, on the fly or more deliberately. One of the most disorienting things about online teaching so far, in fact, is the time lapse: because a lot of materials need to be ready ahead of time, I’m usually working on next week’s lectures and handouts while the students are working on this week’s. (Yes, that gets very confusing sometimes!) If I sense that something isn’t clicking this week, it can be pretty hard to figure out where or how to adapt.

But here I am now, ready once again to take stock of how things are going in my classes. And the disconcerting truth is that a third of the way through this strange term, I still don’t really know, because I have no base line for comparison, no past experience to check this one against. I’m working pretty incessantly on one teaching task or another, but I get very little feedback compared to the ongoing opportunity, in face-to-face teaching, to “read the room”–which could, of course, be discouraging if you could tell they weren’t with you, but at least there was some immediacy to that input and enough flexibility to the whole operation to let you change things up, on the fly or more deliberately. One of the most disorienting things about online teaching so far, in fact, is the time lapse: because a lot of materials need to be ready ahead of time, I’m usually working on next week’s lectures and handouts while the students are working on this week’s. (Yes, that gets very confusing sometimes!) If I sense that something isn’t clicking this week, it can be pretty hard to figure out where or how to adapt. Certainly some parts of this feel easier now than they did at first. The start of term is always chaotic, and this year it was worse than ever before because communicating by writing is just less efficient than talking to people or showing them things directly. (That said, at least when everything is written down there is less chance of details just getting lost or forgotten: the documents are always there for reference! The sheer quantity of written materials becomes its own kind of burden, but there’s still something to be said for having what amounts to a detailed instruction manual for the entire course.) By and large my classes seem to have settled into a rhythm now, though, and as a result the stress has gone down on both sides and the quality of actual work has gone up. It’s clear that the online model is harder for some students who would almost certainly be better off with more external structure and tangible support–but there are also students who find the move away from in-person pressures congenial. At this point I personally feel that, given the option, I would never teach online again: I have not had the transformative experience I’ve heard about from other instructors who ended up wholly converted to this mode of instruction. But it’s early yet, I suppose, and of course right now I don’t have a choice–and in spite of everything, I’m glad about that, as it’s not as if being in the classroom under current circumstances would be a return to the kind of work I loved. I’m also very grateful to have the job security I do, and that, along with my real desire to do the best I can for my students, keeps me pretty motivated and determined to keep trying to do this as well as I can.

Certainly some parts of this feel easier now than they did at first. The start of term is always chaotic, and this year it was worse than ever before because communicating by writing is just less efficient than talking to people or showing them things directly. (That said, at least when everything is written down there is less chance of details just getting lost or forgotten: the documents are always there for reference! The sheer quantity of written materials becomes its own kind of burden, but there’s still something to be said for having what amounts to a detailed instruction manual for the entire course.) By and large my classes seem to have settled into a rhythm now, though, and as a result the stress has gone down on both sides and the quality of actual work has gone up. It’s clear that the online model is harder for some students who would almost certainly be better off with more external structure and tangible support–but there are also students who find the move away from in-person pressures congenial. At this point I personally feel that, given the option, I would never teach online again: I have not had the transformative experience I’ve heard about from other instructors who ended up wholly converted to this mode of instruction. But it’s early yet, I suppose, and of course right now I don’t have a choice–and in spite of everything, I’m glad about that, as it’s not as if being in the classroom under current circumstances would be a return to the kind of work I loved. I’m also very grateful to have the job security I do, and that, along with my real desire to do the best I can for my students, keeps me pretty motivated and determined to keep trying to do this as well as I can. The best thing I can say about my courses right now is that I do finally feel as if I am paying more attention to content than to logistics–which means that when I post about them, I might start talking more about what we’re actually studying in them, like I used to! A trial run: In my intro class (“Literature: How It Works” – a dull title but a pragmatic focus that actually suits my usual approach to first-year classes) we are wrapping up our work on poetry. This week students get to choose a ‘cluster’ of related poems to discuss, hopefully showing off what they have learned about literary devices and poetic form and interpretation so far; then next week we will turn our attention to short stories. I expect a lot of them will like that change of focus; I just hope I can coach them to keep paying attention to details and form and not relax into plot summary.

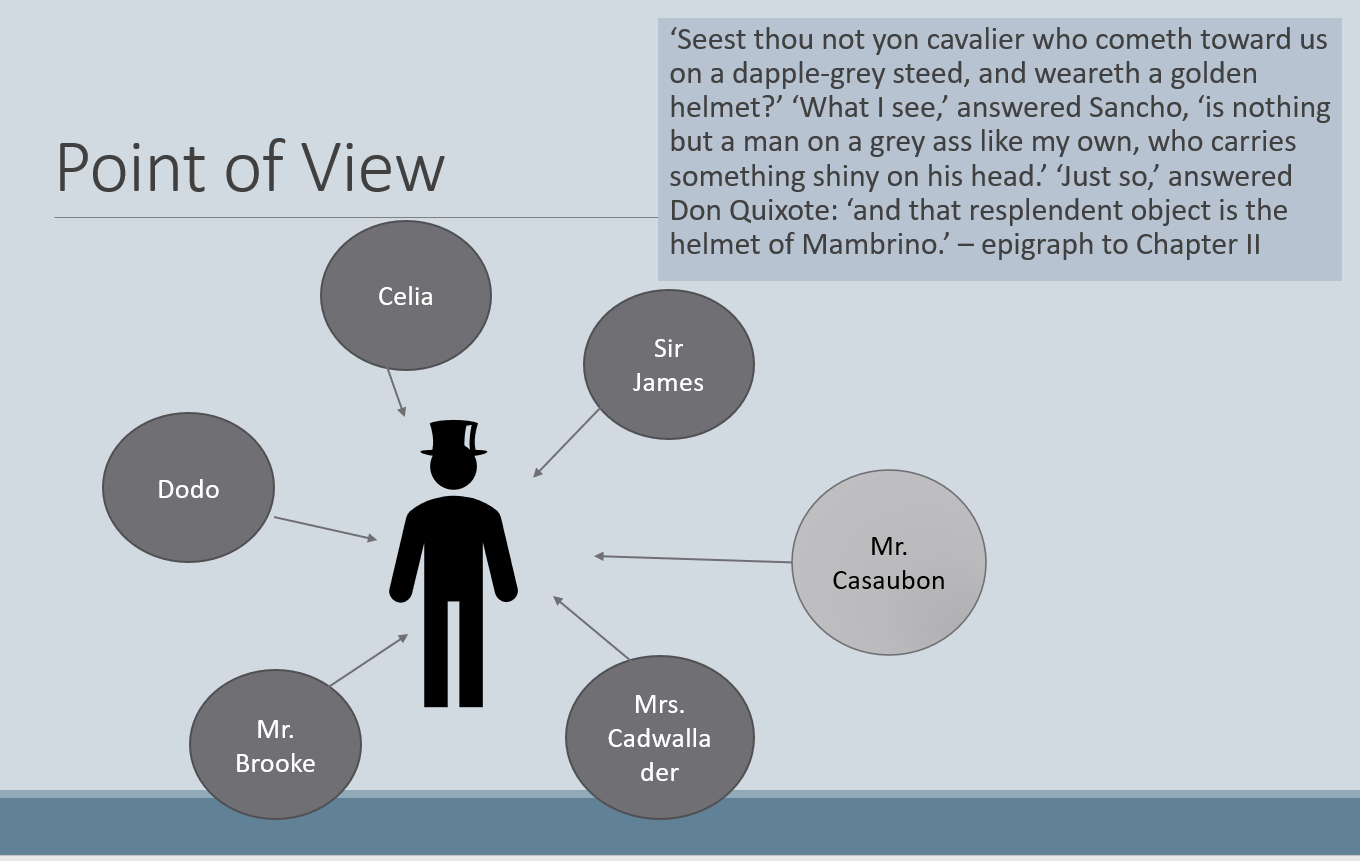

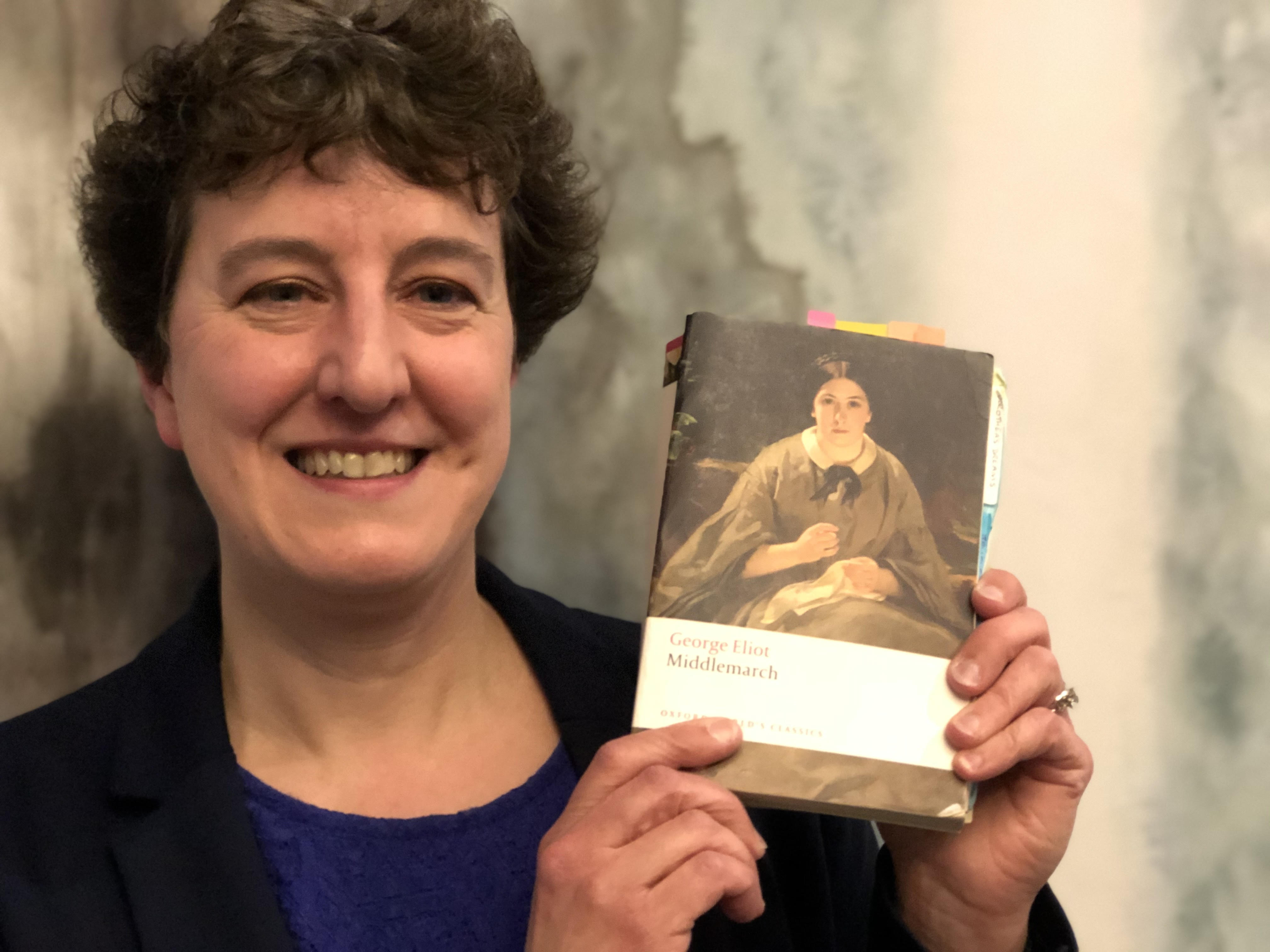

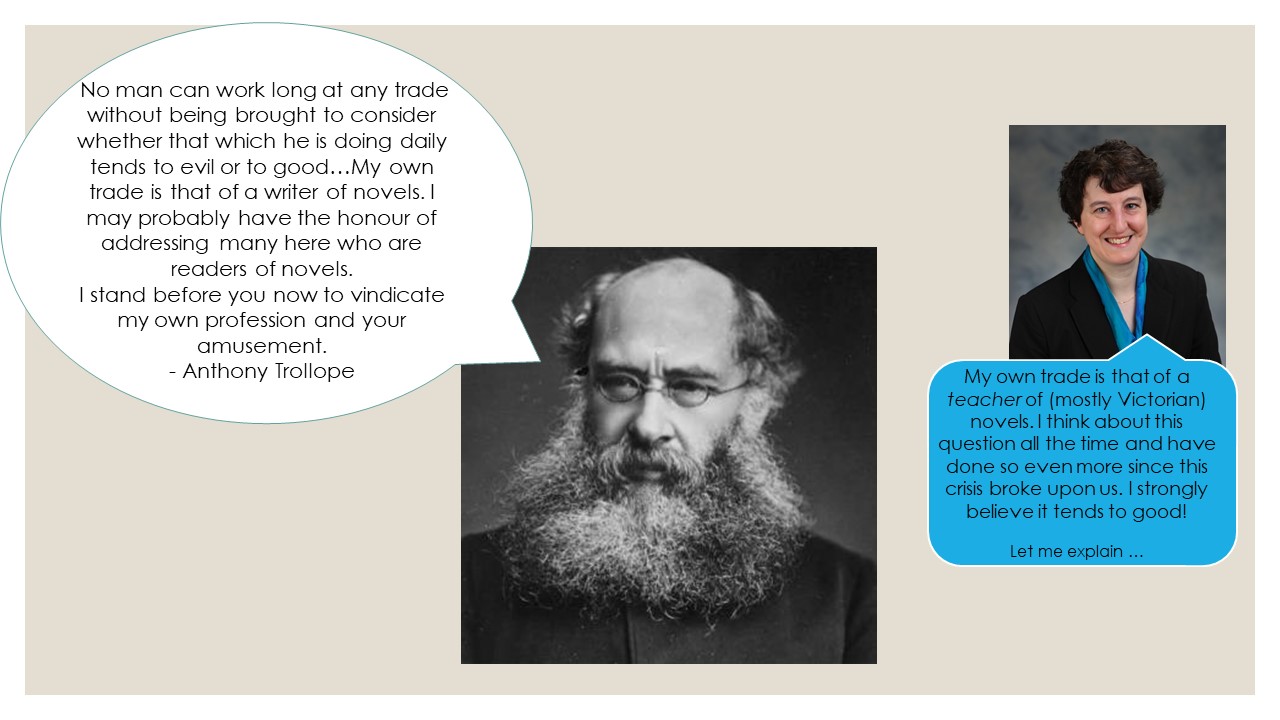

The best thing I can say about my courses right now is that I do finally feel as if I am paying more attention to content than to logistics–which means that when I post about them, I might start talking more about what we’re actually studying in them, like I used to! A trial run: In my intro class (“Literature: How It Works” – a dull title but a pragmatic focus that actually suits my usual approach to first-year classes) we are wrapping up our work on poetry. This week students get to choose a ‘cluster’ of related poems to discuss, hopefully showing off what they have learned about literary devices and poetic form and interpretation so far; then next week we will turn our attention to short stories. I expect a lot of them will like that change of focus; I just hope I can coach them to keep paying attention to details and form and not relax into plot summary. In 19th-Century Fiction we start Middlemarch this week! I, at least, am very excited about this! (Honestly, though: isn’t the cover of the new OWC edition dreadful? They could hardly have made the novel look less fun and inviting. Dorothea is supposed to be blooming, not gloomy!) Rereading the novel and working on my slide presentations to launch our discussions of it has been pretty fun, and also very intellectually challenging, because I have had to make a lot of decisions about how to package the concepts and examples and approaches I would usually lay out over the first few class meetings. While I would certainly do some lecturing in a face-to-face course, I always prefer to draw students towards ideas about how the novel works and what it means through discussion, using a lot of open-ended questions and brainstorming on the white board (where I draw lots of what one of my students [hi, Bea!] recently described as “demented stick figures” 😊). This is hard to reproduce asynchronously!

In 19th-Century Fiction we start Middlemarch this week! I, at least, am very excited about this! (Honestly, though: isn’t the cover of the new OWC edition dreadful? They could hardly have made the novel look less fun and inviting. Dorothea is supposed to be blooming, not gloomy!) Rereading the novel and working on my slide presentations to launch our discussions of it has been pretty fun, and also very intellectually challenging, because I have had to make a lot of decisions about how to package the concepts and examples and approaches I would usually lay out over the first few class meetings. While I would certainly do some lecturing in a face-to-face course, I always prefer to draw students towards ideas about how the novel works and what it means through discussion, using a lot of open-ended questions and brainstorming on the white board (where I draw lots of what one of my students [hi, Bea!] recently described as “demented stick figures” 😊). This is hard to reproduce asynchronously!

I do expect a bit of stuttering as we get going on Middlemarch: my experience of teaching it in the classroom, where I can play ‘cheerleader-in-chief,’ has been that even with me absolutely radiating enthusiasm for it, it can be a hard sell at first, and though I am trying to be as enthusiastic as I can this time too, I have to communicate so much more indirectly that I can’t be sure it will come across, much less be contagious! The stumbling block is usually the amount of exposition, which requires a different kind of attention and patience and can muffle, on a first reading, the sharpness and comedy of the dialogue as well as of the narrator herself. I’m also often surprised by how little students like Dorothea: is idealism so out of fashion these days? But there are always some students who love the book, at first or eventually, and of course my job is not to make them like our readings but to help them learn about them.

I do expect a bit of stuttering as we get going on Middlemarch: my experience of teaching it in the classroom, where I can play ‘cheerleader-in-chief,’ has been that even with me absolutely radiating enthusiasm for it, it can be a hard sell at first, and though I am trying to be as enthusiastic as I can this time too, I have to communicate so much more indirectly that I can’t be sure it will come across, much less be contagious! The stumbling block is usually the amount of exposition, which requires a different kind of attention and patience and can muffle, on a first reading, the sharpness and comedy of the dialogue as well as of the narrator herself. I’m also often surprised by how little students like Dorothea: is idealism so out of fashion these days? But there are always some students who love the book, at first or eventually, and of course my job is not to make them like our readings but to help them learn about them. It has been two weeks since my last post. That sounds almost confessional: forgive me, gentle readers; it has been fourteen days since

It has been two weeks since my last post. That sounds almost confessional: forgive me, gentle readers; it has been fourteen days since  I expressed cautious optimism when the term began and I do still feel some of that, even if at times over the past couple of weeks it has been challenged by fatigue and frustration and sadness. The students are there and most of them are really trying; in my turn, I am doing my level best to demonstrate “instructor presence” and make them feel that I care and am paying attention, not just tracking submissions. I’ve already made a few adjustments to the requirements, too, to reflect what we are all learning about how long all of this takes. Also, although preparing recorded segments is not my favorite thing to do, I find devising topics and shaping them into what seem (to me at least) like engaging little packages intellectually stimulating and even fun sometimes.

I expressed cautious optimism when the term began and I do still feel some of that, even if at times over the past couple of weeks it has been challenged by fatigue and frustration and sadness. The students are there and most of them are really trying; in my turn, I am doing my level best to demonstrate “instructor presence” and make them feel that I care and am paying attention, not just tracking submissions. I’ve already made a few adjustments to the requirements, too, to reflect what we are all learning about how long all of this takes. Also, although preparing recorded segments is not my favorite thing to do, I find devising topics and shaping them into what seem (to me at least) like engaging little packages intellectually stimulating and even fun sometimes.  The readings, too, are as good as they always are, and when I have time to linger over them, that really boosts my morale. I reread the first half of North and South this week (a bit hastily, but still all through) and got excited about the many ways it provokes comparisons with Hard Times, which we are just wrapping up. And in my intro class we are doing Woolf’s “The Death of the Moth,” which was also a tonic to revisit. It’s so beautiful and so sad and so oddly uplifting, in its contemplation of

The readings, too, are as good as they always are, and when I have time to linger over them, that really boosts my morale. I reread the first half of North and South this week (a bit hastily, but still all through) and got excited about the many ways it provokes comparisons with Hard Times, which we are just wrapping up. And in my intro class we are doing Woolf’s “The Death of the Moth,” which was also a tonic to revisit. It’s so beautiful and so sad and so oddly uplifting, in its contemplation of It is hard to know how to begin the 2020-21 iteration of

It is hard to know how to begin the 2020-21 iteration of  So how is it going? One of the oddest things about it, to be honest, is that I really have no idea. The whole past week felt like a massive anti-climax: after months of work, trying to re-train myself and take on board an overwhelming amount of information about “best practices” for online course design and student engagement and teacher presence, after taking a 9-week online course myself to learn about how to do this, after countless hours revising my course outlines and schedules and learning new tools and building my actual Brightspace course sites … all with September 8 as the looming deadline for when the students would “arrive” and the whole experiment would really begin … After all of this, there was no one moment when we were back in class, no online equivalent to that exhilarating and terrifying first face to face session. Instead, because this is how asynchronous online teaching works, students just gradually and on their own timeline started checking in and making their first contributions, while I watched and waited and wondered and tried not to pounce too fast whenever a new notification appeared.

So how is it going? One of the oddest things about it, to be honest, is that I really have no idea. The whole past week felt like a massive anti-climax: after months of work, trying to re-train myself and take on board an overwhelming amount of information about “best practices” for online course design and student engagement and teacher presence, after taking a 9-week online course myself to learn about how to do this, after countless hours revising my course outlines and schedules and learning new tools and building my actual Brightspace course sites … all with September 8 as the looming deadline for when the students would “arrive” and the whole experiment would really begin … After all of this, there was no one moment when we were back in class, no online equivalent to that exhilarating and terrifying first face to face session. Instead, because this is how asynchronous online teaching works, students just gradually and on their own timeline started checking in and making their first contributions, while I watched and waited and wondered and tried not to pounce too fast whenever a new notification appeared.

I’m also genuinely pleased about the contributions that have come in, especially, in both courses, the introductions students have been posting on our “getting to know each other” discussion boards. As I said to them, our first crucial task is to begin building the class into a community, and it has been lovely to see them embrace that goal by telling us a little bit about themselves and then (best of all) responding with great friendliness to each other. I don’t usually solicit individual introductions in all of my F2F classes, only in the smaller seminars, so actually I know more about these groups than I think I ever have this early in the term. While a lot of what I read and practiced this summer was about how to make myself present to my students as a real, if virtual, person, this exercise has been great for making them present to me, not just “students” in the abstract but two really varied and interesting groups of people who bring different perspectives, interests, and needs to our collective enterprise.

I’m also genuinely pleased about the contributions that have come in, especially, in both courses, the introductions students have been posting on our “getting to know each other” discussion boards. As I said to them, our first crucial task is to begin building the class into a community, and it has been lovely to see them embrace that goal by telling us a little bit about themselves and then (best of all) responding with great friendliness to each other. I don’t usually solicit individual introductions in all of my F2F classes, only in the smaller seminars, so actually I know more about these groups than I think I ever have this early in the term. While a lot of what I read and practiced this summer was about how to make myself present to my students as a real, if virtual, person, this exercise has been great for making them present to me, not just “students” in the abstract but two really varied and interesting groups of people who bring different perspectives, interests, and needs to our collective enterprise. Still, I find the spread of the experience out over all hours of the day and all the days of the week disorienting, destabilizing, uncomfortable. Usually my weekly schedule involves regular build-ups to each class meeting: preparing notes and materials and ideas and plans, doing the reading, summoning the energy. Then there’s the live session, which in the moment absorbs all my concentration. When it’s over, I’m drained, even if (especially if!) there has been a really good, lively discussion: being in the moment for that kind of exchange is unlike anything else I do in terms of how focused but also flexible, how attentive to others but also on-task I need to be. I love it, and I really miss it already. I know we can have engaged and intellectually serious exchanges in our online format, but they won’t have the same rhythm, or perhaps any rhythm at all, who knows. Not having to be up and dressed and out the door early in the morning (or ever!) is some compensation, and I expect I will find more of a routine as we settle into the term, but (and I expect I’m going to be saying things like this a lot this term, so sorry for the repetition) it’s a strange new way of being a professor.

Still, I find the spread of the experience out over all hours of the day and all the days of the week disorienting, destabilizing, uncomfortable. Usually my weekly schedule involves regular build-ups to each class meeting: preparing notes and materials and ideas and plans, doing the reading, summoning the energy. Then there’s the live session, which in the moment absorbs all my concentration. When it’s over, I’m drained, even if (especially if!) there has been a really good, lively discussion: being in the moment for that kind of exchange is unlike anything else I do in terms of how focused but also flexible, how attentive to others but also on-task I need to be. I love it, and I really miss it already. I know we can have engaged and intellectually serious exchanges in our online format, but they won’t have the same rhythm, or perhaps any rhythm at all, who knows. Not having to be up and dressed and out the door early in the morning (or ever!) is some compensation, and I expect I will find more of a routine as we settle into the term, but (and I expect I’m going to be saying things like this a lot this term, so sorry for the repetition) it’s a strange new way of being a professor. As for specifics, well, we’re discussing Seamus Heaney’s “Digging” and Adrienne Rich’s “Aunt Jennifer’s Tiger” in my intro class this coming week, and in 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Hard Times (which I assigned this term because we ended up cutting it last term when we ‘pivoted’ to online). These are all texts I like a lot, though in my experience Hard Times is often a hard sell, even to students who otherwise like Dickens (which is never all of them, of course). Will I be able to communicate my enthusiasm and generate the kinds of discussions I aspire to in the classroom without being in the classroom? I guess I’ll find out. I’m trying to create recorded lectures that open up into writing prompts, rather than drawing conclusions, much as I would move in the classroom through laying out some ideas, contexts, or questions and then opening things up to their input. I am actually having some fun with this, though yet one more unknown is how effective my first attempts will be. I have the next two weeks of material nearly completed, so that buys me a bit of time: as I see what works and what doesn’t, and which approach to the lectures they prefer, I can adapt the next round accordingly.

As for specifics, well, we’re discussing Seamus Heaney’s “Digging” and Adrienne Rich’s “Aunt Jennifer’s Tiger” in my intro class this coming week, and in 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Hard Times (which I assigned this term because we ended up cutting it last term when we ‘pivoted’ to online). These are all texts I like a lot, though in my experience Hard Times is often a hard sell, even to students who otherwise like Dickens (which is never all of them, of course). Will I be able to communicate my enthusiasm and generate the kinds of discussions I aspire to in the classroom without being in the classroom? I guess I’ll find out. I’m trying to create recorded lectures that open up into writing prompts, rather than drawing conclusions, much as I would move in the classroom through laying out some ideas, contexts, or questions and then opening things up to their input. I am actually having some fun with this, though yet one more unknown is how effective my first attempts will be. I have the next two weeks of material nearly completed, so that buys me a bit of time: as I see what works and what doesn’t, and which approach to the lectures they prefer, I can adapt the next round accordingly.

Good as she is, James turns out to be a poor choice for binge-reading, and yet a plan is a plan and a deadline is a deadline, so I have been persisting. The endeavor is not without its rewards: again, she’s good– very good, even! It’s just that she’s always good in exactly the same way, sometimes even in the exact same words. I was trying to think of other authors who have stood up better to this kind of determined march through their works. I remember really enjoying myself when I read all of Trollope’s Palliser novels straight through many years ago, and I have always loved rereading the Lymond Chronicles start to finish–but stories accumulate in a different way in those than in most detective series. While we are interested in and generally grow attached to the investigators in a long-running series, if the novels become more about them than about detecting, we’ve probably shifted genres–though having said that, counter-examples immediately occur to me, including Elizabeth George and Tana French, and of course there’s Gaudy Night, which perfectly balances case and character. In James’s novels, in any case, the personal arcs of her recurring cast are always peripheral to the main action, and while that strikes me as a principled decision, formally, it also has constricting effects. By the end of The Lighthouse I was far more interested in Dalgliesh’s relationship with Emma Lavenham than in whodunit–and that too is something my essay will most likely take up.

Good as she is, James turns out to be a poor choice for binge-reading, and yet a plan is a plan and a deadline is a deadline, so I have been persisting. The endeavor is not without its rewards: again, she’s good– very good, even! It’s just that she’s always good in exactly the same way, sometimes even in the exact same words. I was trying to think of other authors who have stood up better to this kind of determined march through their works. I remember really enjoying myself when I read all of Trollope’s Palliser novels straight through many years ago, and I have always loved rereading the Lymond Chronicles start to finish–but stories accumulate in a different way in those than in most detective series. While we are interested in and generally grow attached to the investigators in a long-running series, if the novels become more about them than about detecting, we’ve probably shifted genres–though having said that, counter-examples immediately occur to me, including Elizabeth George and Tana French, and of course there’s Gaudy Night, which perfectly balances case and character. In James’s novels, in any case, the personal arcs of her recurring cast are always peripheral to the main action, and while that strikes me as a principled decision, formally, it also has constricting effects. By the end of The Lighthouse I was far more interested in Dalgliesh’s relationship with Emma Lavenham than in whodunit–and that too is something my essay will most likely take up. I have been trying to read other things when I’ve had the energy, which hasn’t been often. I gave up on A Time of Gifts, though, which shames me somewhat to admit but there it is. There was a lot of fine writing but I couldn’t catch any momentum from it, and it turns out not to be as diverting as I’d hoped to read about someone else’s travels while unable to go anywhere myself. I’ve read a handful of romance novels–Christina Lauren’s The Unhoneymooners, Talia Hibbert’s Take a Hint, Dani Brown, and (most of) Jasmine Guillory’s Party of Two–just meh, all of them. I’m a hundred pages or so into Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian and it seems promising; once I finish The Private Patient, I want to settle in and really give it a chance. I’ve also just read Sarah Moss’s forthcoming Summerwater — but I have to save up what I think about that for the review I’ll be writing for the Dublin Review of Books.

I have been trying to read other things when I’ve had the energy, which hasn’t been often. I gave up on A Time of Gifts, though, which shames me somewhat to admit but there it is. There was a lot of fine writing but I couldn’t catch any momentum from it, and it turns out not to be as diverting as I’d hoped to read about someone else’s travels while unable to go anywhere myself. I’ve read a handful of romance novels–Christina Lauren’s The Unhoneymooners, Talia Hibbert’s Take a Hint, Dani Brown, and (most of) Jasmine Guillory’s Party of Two–just meh, all of them. I’m a hundred pages or so into Isabella Hammad’s The Parisian and it seems promising; once I finish The Private Patient, I want to settle in and really give it a chance. I’ve also just read Sarah Moss’s forthcoming Summerwater — but I have to save up what I think about that for the review I’ll be writing for the Dublin Review of Books.

Then, instead of having three distinct conversations about the reading on three separate days (which, again, has always allowed me to pace us, and to model sorting out specific interpretive elements rather than facing everything that’s going on in the novel all at once), we’ll have discussion boards. Presumably, the topics will reflect the same questions I usually set in class, but I’m not sure if I should try to move us through these topics in some kind of sequence across the week, as I would in person, or think of the module as weighted towards reading at the beginning of the week and discussion at the end of the week. Probably the latter–though they might miss getting input and ideas from each other (and from me) earlier in their reading. I don’t want to be micromanaging participation on the discussion boards too much: I’m imagining how strange this all might feel to them, and ideally I’d like it to feel both easy and sort of natural to contribute. Super-rigid requirements (post once by Wednesday, reply once on Thursday, post again on Friday–whatever) really work against that and give me a lot to keep track of.

Then, instead of having three distinct conversations about the reading on three separate days (which, again, has always allowed me to pace us, and to model sorting out specific interpretive elements rather than facing everything that’s going on in the novel all at once), we’ll have discussion boards. Presumably, the topics will reflect the same questions I usually set in class, but I’m not sure if I should try to move us through these topics in some kind of sequence across the week, as I would in person, or think of the module as weighted towards reading at the beginning of the week and discussion at the end of the week. Probably the latter–though they might miss getting input and ideas from each other (and from me) earlier in their reading. I don’t want to be micromanaging participation on the discussion boards too much: I’m imagining how strange this all might feel to them, and ideally I’d like it to feel both easy and sort of natural to contribute. Super-rigid requirements (post once by Wednesday, reply once on Thursday, post again on Friday–whatever) really work against that and give me a lot to keep track of. I think the next step for me is actually to back away from the overwhelming amount of information and advice I’ve been contemplating about online teaching and go back to my actual teaching notes. Looking at the topics I usually cover with a modular redesign in mind will probably help me realize ways in which these bundles would actually work and think in more concrete ways about just how different the online experience needs or doesn’t need to be. Precisely because I’ve been teaching 19th-century fiction in such a similar way for so long, it is the one that feels the strangest to mess with, but it’s also the one where I have the simplest overall goal–to have the best conversations we can about our readings–and the most faith in the books themselves to get us talking, one way or another. Even if I don’t get everything right on my first attempt to do all this online, at least we’ll still be working our way through Middlemarch!

I think the next step for me is actually to back away from the overwhelming amount of information and advice I’ve been contemplating about online teaching and go back to my actual teaching notes. Looking at the topics I usually cover with a modular redesign in mind will probably help me realize ways in which these bundles would actually work and think in more concrete ways about just how different the online experience needs or doesn’t need to be. Precisely because I’ve been teaching 19th-century fiction in such a similar way for so long, it is the one that feels the strangest to mess with, but it’s also the one where I have the simplest overall goal–to have the best conversations we can about our readings–and the most faith in the books themselves to get us talking, one way or another. Even if I don’t get everything right on my first attempt to do all this online, at least we’ll still be working our way through Middlemarch! Well, it’s official:

Well, it’s official:  Having the decision made for me by circumstances hasn’t changed everything about how I feel about teaching online, but it has made a lot of those feelings irrelevant. Also, countering my wistfulness about what we’ll be missing are other, stronger feelings about what we will, happily, be avoiding by staying behind our screens. Every description I’ve seen of ways to make face-to-face teaching more or less safe for everyone involved has involved a level of surveillance, anxiety, and uncertainty that I think would make it nearly impossible to teach or learn with confidence: a lot of what is good about meeting in person would be distorted by the necessary health and safety measures, and even without taking into account the accessibility issues for staff, students, and faculty who would be at higher risk, being in a constant state of vigilance would be exhausting for everyone. Frankly, I’m relieved and grateful that Dalhousie has finally made a clear call that (arguably) errs on the side of caution. Now we can get on with planning for it.

Having the decision made for me by circumstances hasn’t changed everything about how I feel about teaching online, but it has made a lot of those feelings irrelevant. Also, countering my wistfulness about what we’ll be missing are other, stronger feelings about what we will, happily, be avoiding by staying behind our screens. Every description I’ve seen of ways to make face-to-face teaching more or less safe for everyone involved has involved a level of surveillance, anxiety, and uncertainty that I think would make it nearly impossible to teach or learn with confidence: a lot of what is good about meeting in person would be distorted by the necessary health and safety measures, and even without taking into account the accessibility issues for staff, students, and faculty who would be at higher risk, being in a constant state of vigilance would be exhausting for everyone. Frankly, I’m relieved and grateful that Dalhousie has finally made a clear call that (arguably) errs on the side of caution. Now we can get on with planning for it. As my regret about the shift to online has been replaced by determination to make the best of it, I’ve also noticed something I’ve seen experienced online teachers point out before, which is a tendency to idealize face-to-face teaching, as if just being there in person guarantees good pedagogy. It doesn’t, of course. In my own case, I know that what I’ll miss the most is lively in-class discussions. But if I’m being honest, I have to admit that even the liveliest discussion rarely involves everyone in the room. Of course I try hard to engage as many people as possible, using a range of different strategies depending on the class size and purpose and layout: break-out groups, think-pair-share exercises, free writing from discussion prompts, discussion questions circulated ahead of time, handouts with passages to annotate and share, or just the good old-fashioned technique “ask a provocative question and see where it gets us.” Even what feels to me like a very good result, though, might actually involve 10 people out of, say, 40 — or 90, or 120 — speaking up. Others are (hopefully!) engaged in different ways, and there are different ways, too, to ask for and measure participation than counting who speaks up in class. Still, I’d be fooling myself if I pretended that there wasn’t any room for improvement–and what I want to think about as I make plans for the fall is therefore not how to try to duplicate that in-class experience online (ugh, Zoom!), partly because we are supposed to focus on asynchronous methods but also because maybe I can use online tools to get a higher contribution rate, which in turn might make more students feel a part of our collective enterprise. And, not incidentally, if all contributions are written, they will also get more (low-stakes) writing practice, which is always a good thing, and they will be able to think first, and more slowly (if that suits them), and look things up in the text, before having to weigh in.

As my regret about the shift to online has been replaced by determination to make the best of it, I’ve also noticed something I’ve seen experienced online teachers point out before, which is a tendency to idealize face-to-face teaching, as if just being there in person guarantees good pedagogy. It doesn’t, of course. In my own case, I know that what I’ll miss the most is lively in-class discussions. But if I’m being honest, I have to admit that even the liveliest discussion rarely involves everyone in the room. Of course I try hard to engage as many people as possible, using a range of different strategies depending on the class size and purpose and layout: break-out groups, think-pair-share exercises, free writing from discussion prompts, discussion questions circulated ahead of time, handouts with passages to annotate and share, or just the good old-fashioned technique “ask a provocative question and see where it gets us.” Even what feels to me like a very good result, though, might actually involve 10 people out of, say, 40 — or 90, or 120 — speaking up. Others are (hopefully!) engaged in different ways, and there are different ways, too, to ask for and measure participation than counting who speaks up in class. Still, I’d be fooling myself if I pretended that there wasn’t any room for improvement–and what I want to think about as I make plans for the fall is therefore not how to try to duplicate that in-class experience online (ugh, Zoom!), partly because we are supposed to focus on asynchronous methods but also because maybe I can use online tools to get a higher contribution rate, which in turn might make more students feel a part of our collective enterprise. And, not incidentally, if all contributions are written, they will also get more (low-stakes) writing practice, which is always a good thing, and they will be able to think first, and more slowly (if that suits them), and look things up in the text, before having to weigh in. There are other ways in which (and we all know this to be true) face-to-face teaching isn’t perfect, and there are also teachers whose face-to-face teaching does not reflect best practices for that medium. Given these obvious truths, and especially since the shift to online teaching is driven by factors that themselves have nothing to do with pedagogical preferences, I have been getting pretty irritable about professors publicly lamenting these decisions, especially when it’s obvious that they haven’t made the slightest effort to learn anything about online teaching, or to reflect on the limitations of their own usual pedagogy. One prominent academic just published an op-ed in a national paper declaring that online teaching can only ever be a faint shadow of “the real thing”; others have been making snide remarks on Twitter about the obvious worthlessness of a term of “crap zoom lectures” (that’s verbatim) or questioning why students should pay tuition for the equivalent of podcasts. Besides the obvious PR downside of making these sweepingly negative and ill-informed statements when your institutions are turning themselves upside down to find sustainable ways forward, what kind of attitude does that model for our students? The situation is hard, I agree, and sad, and disappointing. But at the end of the day we are professionals and this, right now, is what our job requires. If we value that job–and I don’t mean that in the reductive “it’s what we get paid for” way (though for those of us with tenured positions, that professional obligation is important to acknowledge and live up to) but our commitment to teaching and training and nurturing our students–then, if we can*, I think we need to do our best to get on with it.

There are other ways in which (and we all know this to be true) face-to-face teaching isn’t perfect, and there are also teachers whose face-to-face teaching does not reflect best practices for that medium. Given these obvious truths, and especially since the shift to online teaching is driven by factors that themselves have nothing to do with pedagogical preferences, I have been getting pretty irritable about professors publicly lamenting these decisions, especially when it’s obvious that they haven’t made the slightest effort to learn anything about online teaching, or to reflect on the limitations of their own usual pedagogy. One prominent academic just published an op-ed in a national paper declaring that online teaching can only ever be a faint shadow of “the real thing”; others have been making snide remarks on Twitter about the obvious worthlessness of a term of “crap zoom lectures” (that’s verbatim) or questioning why students should pay tuition for the equivalent of podcasts. Besides the obvious PR downside of making these sweepingly negative and ill-informed statements when your institutions are turning themselves upside down to find sustainable ways forward, what kind of attitude does that model for our students? The situation is hard, I agree, and sad, and disappointing. But at the end of the day we are professionals and this, right now, is what our job requires. If we value that job–and I don’t mean that in the reductive “it’s what we get paid for” way (though for those of us with tenured positions, that professional obligation is important to acknowledge and live up to) but our commitment to teaching and training and nurturing our students–then, if we can*, I think we need to do our best to get on with it. And happily, though most of us are not trained as online teachers, we do have a superpower that should help us out: we are trained researchers! We can look things up, consult experts, examine models, and figure out how to apply what we learn to our own situations, contexts, pedagogical goals, and values. At this point, that’s what I’m working on: learning about online learning. Yes, I had other projects I was interested in pursuing this summer. In fact, I still do, but I have scaled back my expectations for them, because I can’t think of anything that’s more important right now than doing everything I can to make my fall classes good experiences, for my students and also for me. I have the privilege of a full-time continuing position, after all, and my university is making experts and resources available to me–plus there are all kinds of people generously offering guidance and encouragement through Twitter and I have been following up their leads and bookmarking

And happily, though most of us are not trained as online teachers, we do have a superpower that should help us out: we are trained researchers! We can look things up, consult experts, examine models, and figure out how to apply what we learn to our own situations, contexts, pedagogical goals, and values. At this point, that’s what I’m working on: learning about online learning. Yes, I had other projects I was interested in pursuing this summer. In fact, I still do, but I have scaled back my expectations for them, because I can’t think of anything that’s more important right now than doing everything I can to make my fall classes good experiences, for my students and also for me. I have the privilege of a full-time continuing position, after all, and my university is making experts and resources available to me–plus there are all kinds of people generously offering guidance and encouragement through Twitter and I have been following up their leads and bookmarking  In spite of everything, our academic term here is wrapping up on schedule: we are now in the middle of our exam period, final grades are due May 1, and a week or two after that my department will hold a remote version of our annual “

In spite of everything, our academic term here is wrapping up on schedule: we are now in the middle of our exam period, final grades are due May 1, and a week or two after that my department will hold a remote version of our annual “

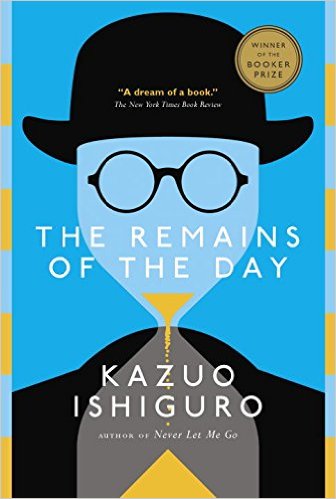

I guess that’s a sort of peroration, isn’t it? Apparently I’m working them in wherever I see an opportunity. Anyway, it’s odd and a bit sad to be wrapping up a term and feel so deflated about it. I think one reason it hits hard is that I spent so much time planning for this one, especially for the Brit Lit survey class–and I was so excited about Three Guineas and about moving from it to The Remains of the Day. Ordinarily at this point I would be throwing myself into choosing the readings for my first-year class in the fall, as instead of doing Pulp Fiction again I am taking on a section of “Literature: How It Works”; I’m finding that hard to focus on, though, both because there’s a lot I still don’t know about what kind or size of class it will be and because I have lost some enthusiasm for advance planning given how much I had to toss out this term. I did put in an order for the books for 19th-Century Fiction from Dickens to Hardy, but for whatever reason, for the first time I can remember it is not filling well (and it’s not, or not obviously, a coronavirus thing, as many of our other courses at that level seem to be filling up just fine) so that’s a bit deflating as well. But there’s time for all of this to get sorted.

I guess that’s a sort of peroration, isn’t it? Apparently I’m working them in wherever I see an opportunity. Anyway, it’s odd and a bit sad to be wrapping up a term and feel so deflated about it. I think one reason it hits hard is that I spent so much time planning for this one, especially for the Brit Lit survey class–and I was so excited about Three Guineas and about moving from it to The Remains of the Day. Ordinarily at this point I would be throwing myself into choosing the readings for my first-year class in the fall, as instead of doing Pulp Fiction again I am taking on a section of “Literature: How It Works”; I’m finding that hard to focus on, though, both because there’s a lot I still don’t know about what kind or size of class it will be and because I have lost some enthusiasm for advance planning given how much I had to toss out this term. I did put in an order for the books for 19th-Century Fiction from Dickens to Hardy, but for whatever reason, for the first time I can remember it is not filling well (and it’s not, or not obviously, a coronavirus thing, as many of our other courses at that level seem to be filling up just fine) so that’s a bit deflating as well. But there’s time for all of this to get sorted. I’m not sure whether I’m surprised that it has already been three weeks since we began extreme social distancing here or surprised that it hasn’t been even longer — normalcy itself seems so distant now! It seems remote in both directions, too: hard as it is to think back on the relative simplicity of ordinary life before, it is even harder to look ahead because there is so much uncertainty about when and how those conditions will return. That’s as good an argument as any for trying to take this massive disruption one day at a time, which is certainly what I have been trying to do. My success varies, as does my ability to get through each day with anything like the (again, relative) equanimity and focus I used to have.

I’m not sure whether I’m surprised that it has already been three weeks since we began extreme social distancing here or surprised that it hasn’t been even longer — normalcy itself seems so distant now! It seems remote in both directions, too: hard as it is to think back on the relative simplicity of ordinary life before, it is even harder to look ahead because there is so much uncertainty about when and how those conditions will return. That’s as good an argument as any for trying to take this massive disruption one day at a time, which is certainly what I have been trying to do. My success varies, as does my ability to get through each day with anything like the (again, relative) equanimity and focus I used to have.

Anyway, it quickly became clear that the right strategy (and, to their credit, the one our administrators have been urging) is not to try to replicate electronically all of our plans for the last few weeks of term, including the final exam period, but to smooth students’ paths to completion as best we can: dropping readings and assignments and giving them options including taking the grade they have earned so far but still also allowing another chance to do better in as painless a way as we can think of. I think the options I came up with for my classes are pretty good, in these respects, but it may be that they don’t go far enough, because this is all turning out to be so much harder than it sounded a week ago–and of course however we might (or might not!) be managing, our students have their own specific circumstances which may make even the most “reasonable” alternatives too much. I have been feeling a lot of regret about the books we won’t get to, especially The Remains of the Day, which I was increasingly excited about as the capstone text for the survey class–what a good book to read right after Three Guineas! As for Three Guineas itself, I was so excited about teaching it for the first time. It’s definitely going back on my syllabus the next time it fits the brief. Sigh.

Anyway, it quickly became clear that the right strategy (and, to their credit, the one our administrators have been urging) is not to try to replicate electronically all of our plans for the last few weeks of term, including the final exam period, but to smooth students’ paths to completion as best we can: dropping readings and assignments and giving them options including taking the grade they have earned so far but still also allowing another chance to do better in as painless a way as we can think of. I think the options I came up with for my classes are pretty good, in these respects, but it may be that they don’t go far enough, because this is all turning out to be so much harder than it sounded a week ago–and of course however we might (or might not!) be managing, our students have their own specific circumstances which may make even the most “reasonable” alternatives too much. I have been feeling a lot of regret about the books we won’t get to, especially The Remains of the Day, which I was increasingly excited about as the capstone text for the survey class–what a good book to read right after Three Guineas! As for Three Guineas itself, I was so excited about teaching it for the first time. It’s definitely going back on my syllabus the next time it fits the brief. Sigh. One of the most emotionally painful parts of all of this has been the abrupt severance of personal relationships, which is what teaching is really all about. I have put course materials together to get us to the end of our current texts, but it is much less rewarding scripting them than it is taking my ideas and questions in to meet them with and seeing what comes of our encounter. Sure, it doesn’t always go swimmingly, but that just means you try again, or try something different. I know there are ways to include more personal and “synchronous” interaction (as we’ve quickly learned to label it!) in online teaching, and of course as someone who spends a lot of time online I already believe that you can cultivate meaningful relationships without meeting face to face. There just isn’t time for that now, though, and also the demands those tools put on everyone to be available and attentive at the same time are all wrong for our immediate circumstances. It isn’t just about finding ways to get through the course material together either: there are students I have been working with for years who it turns out I saw in person for maybe the last time that Friday without even knowing it. I have been thinking about them, and about all of my students, so much since that hectic departure from campus and hoping they know how much I have valued our time together and how much I already miss them!

One of the most emotionally painful parts of all of this has been the abrupt severance of personal relationships, which is what teaching is really all about. I have put course materials together to get us to the end of our current texts, but it is much less rewarding scripting them than it is taking my ideas and questions in to meet them with and seeing what comes of our encounter. Sure, it doesn’t always go swimmingly, but that just means you try again, or try something different. I know there are ways to include more personal and “synchronous” interaction (as we’ve quickly learned to label it!) in online teaching, and of course as someone who spends a lot of time online I already believe that you can cultivate meaningful relationships without meeting face to face. There just isn’t time for that now, though, and also the demands those tools put on everyone to be available and attentive at the same time are all wrong for our immediate circumstances. It isn’t just about finding ways to get through the course material together either: there are students I have been working with for years who it turns out I saw in person for maybe the last time that Friday without even knowing it. I have been thinking about them, and about all of my students, so much since that hectic departure from campus and hoping they know how much I have valued our time together and how much I already miss them! And now, I guess, it’s time to settle in to what people keep euphemistically calling “the new normal.” Here in Halifax we are under strong directions for social distancing; I’ve heard rumors that something more rigorous might be coming, in the hope of really flattening that infamous curve. There are lots of wry jokes and memes about readers or introverts or others whose habits and preferences mean they have been “preparing for this moment our whole lives.” We live a pretty quiet life ourselves, so to some extent this is true of us as well (though not of Maddie, who like many young people is going to be very well served by the various ways she and her friends can stay in touch virtually). It’s pretty different having to stay home, though, and also worrying whenever you go out, even if it’s only for essentials. It’s also not spring yet here–I envy my family in Vancouver the softening weather that makes walks and parks and gardens good options. I am grateful, though, that we are comfortable and together and, so far, healthy. I am also glad I did pick up An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good, because I finished reading it this morning and it is a nice bit of twisted fun…about which more soon, I hope!

And now, I guess, it’s time to settle in to what people keep euphemistically calling “the new normal.” Here in Halifax we are under strong directions for social distancing; I’ve heard rumors that something more rigorous might be coming, in the hope of really flattening that infamous curve. There are lots of wry jokes and memes about readers or introverts or others whose habits and preferences mean they have been “preparing for this moment our whole lives.” We live a pretty quiet life ourselves, so to some extent this is true of us as well (though not of Maddie, who like many young people is going to be very well served by the various ways she and her friends can stay in touch virtually). It’s pretty different having to stay home, though, and also worrying whenever you go out, even if it’s only for essentials. It’s also not spring yet here–I envy my family in Vancouver the softening weather that makes walks and parks and gardens good options. I am grateful, though, that we are comfortable and together and, so far, healthy. I am also glad I did pick up An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good, because I finished reading it this morning and it is a nice bit of twisted fun…about which more soon, I hope!