I have read some books since Fayne, honest I have! I just haven’t had the bandwidth, as the saying goes, to write them up properly—which is a shame, as some of them have been very good. So here’s a catch-up post, to be sure I don’t let them slip by entirely unremarked.

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place.

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place.

I just loved this novel, which struck me as elegantly balanced between Standish’s individual experience, written with a pitch-perfect blend of comedy and pathos, and parable-like reflections on life and death more generally. Three small samples, just as teasers, from different moments in the book—one from before Standish’s slip and fall, one from his time in the water, and the other from the perspective of one of his shipboard companions:

The whole world was so quiet that Standish felt mystified. The lone ship plowing through the broad sea, the myriad of stars fading out of the wide heavens—these were all elemental things that soothed and troubled Standish. It was as if he were learning for the first time that all the vexatious problems of his life were meaningless and unimportant; and yet he felt ashamed at having had them in the same world that could create such a scene as this.

Not dead yet, Standish thought. And not alive either; before walking away and leaving his inert remains to shift for themselves it would be best to think of life as he had lived it; not of the ordinary events . . . but of the extraordinary things that had happened in his insufficient thirty-five years. And with each thought a pang came to his heart that had shattered, a pang of regret that he could not go on like other men having new extraordinary experiences day after day.

He went down to his favorite spot on the well deck and gazed out at the sea and the materializing stars in the heaven. It defied his imagination. You could not think of this vastness one moment and then the next moment think of a puny bundle of humanity lost in its midst. One was so much bigger than the other; the human mind simply could not cope with the two together.

I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite:

I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite:

The Flaw

The best thing about a hand-made pattern

is the flaw.

Sooner or later in a hand-loomed rug,

among the squares and flattened triangles,

a little red nub might soar above a blue field,

or a purple cross might sneak in between

the neat ochre teeth of the border.

The flaw we live by, the wrong color floss,

now wreathes among the uniform strands

and, because it does not match,

makes a red bird fly,

turning blue field into sky.

It is almost, after long silence, a word

spoken aloud, a hand saying through the flaw,

I’m alive, discovered by your eye.

Peacock talks often in the book about her interest in poetic form; I liked this explanation of its value:

Form does something else vigorously physical: it compresses. Because you have to meet a limit—a line length, a number of syllables, a rhyme—you have to stretch or curl a thought to meet that requirement. Curiously, as the lyrical mind works to answer that demand, the unconscious is freed to experience its most playful and most dangerous feelings. Form is safety, the safe place in which we can be most volatile.

A Friend Sails in on a Poem is not an effusive book, but there’s something uplifting about its record of a friendship between women that is shaped by shared artistic and intellectual interests and not threatened by the differences between them as people and as writers. There’s no melodrama, not even really any narrative tension, around their friendship; the book’s momentum comes solely and, I thought, admirably simply from the movement of the two poets in tandem through time.

I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer.

I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer.

Smith’s story also felt very specific, very particular to me. She remarks in a few instances that she is writing it because perhaps it will become something other people can use, but her care not to extrapolate or generalize, while I suppose appropriate to such a personal kind of memoir, seemed to me to work against that possibility. Others might well disagree, and I can see making the argument that the portable value of her book lies precisely in its modeling of how to be honest and vulnerable about something so intimate. In the spirit of her viral poem “Good Bones,” You Could Make This Place Beautiful (a title which itself comes from that poem), Smith’s book is, ultimately, about repair, about how even a situation that seems like a hopeless ruin can, with some time and a lot of effort, become habitable again:

Something about being at the ocean always reminds me of how small I am, but not in a way that makes me feel insignificant. It’s a smallness that makes me feel a part of the world, not separate from it. I sat down in a lounge chair and opened the magazine to my poem [“Bride”], the thin pages flapping in the wind. IN that moment, I felt like I was where I was meant to be, doing what I was supposed to be doing.

Life, like a poem, is a series of choices.

Something had shifted, maybe just slightly, but perceptibly. I remember feeling the smile on my face the whole walk back to the hotel, hoping it didn’t seem odd to the people around me. I stopped at the drawbridge that lifted so the boats could go under. The whole street lifted up right in front of me. Nothing seemed impossible anymore. Everything was possible.

OK, maybe! The optimism is welcome, and maybe authentic, though (and again, others might disagree) it feels a bit forced to me here, whereas “Good Bones” has a quality of wistfulness to it that I like better.

Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his Slough House books that I’ve read. It was thoroughly entertaining, and I read it at a brisk pace as a result, but by the end it did strike me as a risk that the series’ signature elements, including Lamb’s flatulence and the various other Slow Horses’ quirks, could wear a bit thin.

Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his Slough House books that I’ve read. It was thoroughly entertaining, and I read it at a brisk pace as a result, but by the end it did strike me as a risk that the series’ signature elements, including Lamb’s flatulence and the various other Slow Horses’ quirks, could wear a bit thin.

I’m reading for work too, of course, most recently The Murder of Roger Ackroyd in Mystery & Detective Fiction and a cluster of works on ‘fallen women’ for my Victorian ‘Woman Question’ seminar—DGR’s “Jenny,” Augusta Webster’s “A Castaway,” and Elizabeth Gaskell’s “Lizzie Leigh,” a story I love (I wrote about it here the last time I taught it in person, which seems a lifetime ago). As always, I am thinking about ways to shake up the reading list for the mystery class, if only to bring in at least one book more recent than the early 1990s, which used to seem very current but of course is not any longer. A student asked today, in the context of our discussion of the moral discomfort possibly created by the “cozy” subgenre, whether we were going to talk about true crime in the course. We aren’t, because no example of it is assigned and because the course is specifically about crime “fiction”, but one idea I’ve been kicking around is Denise Mina’s The Long Drop, which is a novelization of a true crime case. I haven’t read it yet, so that’s obviously what I need to do next, but I listened to a podcast episode with her talking about it and it was really fascinating.

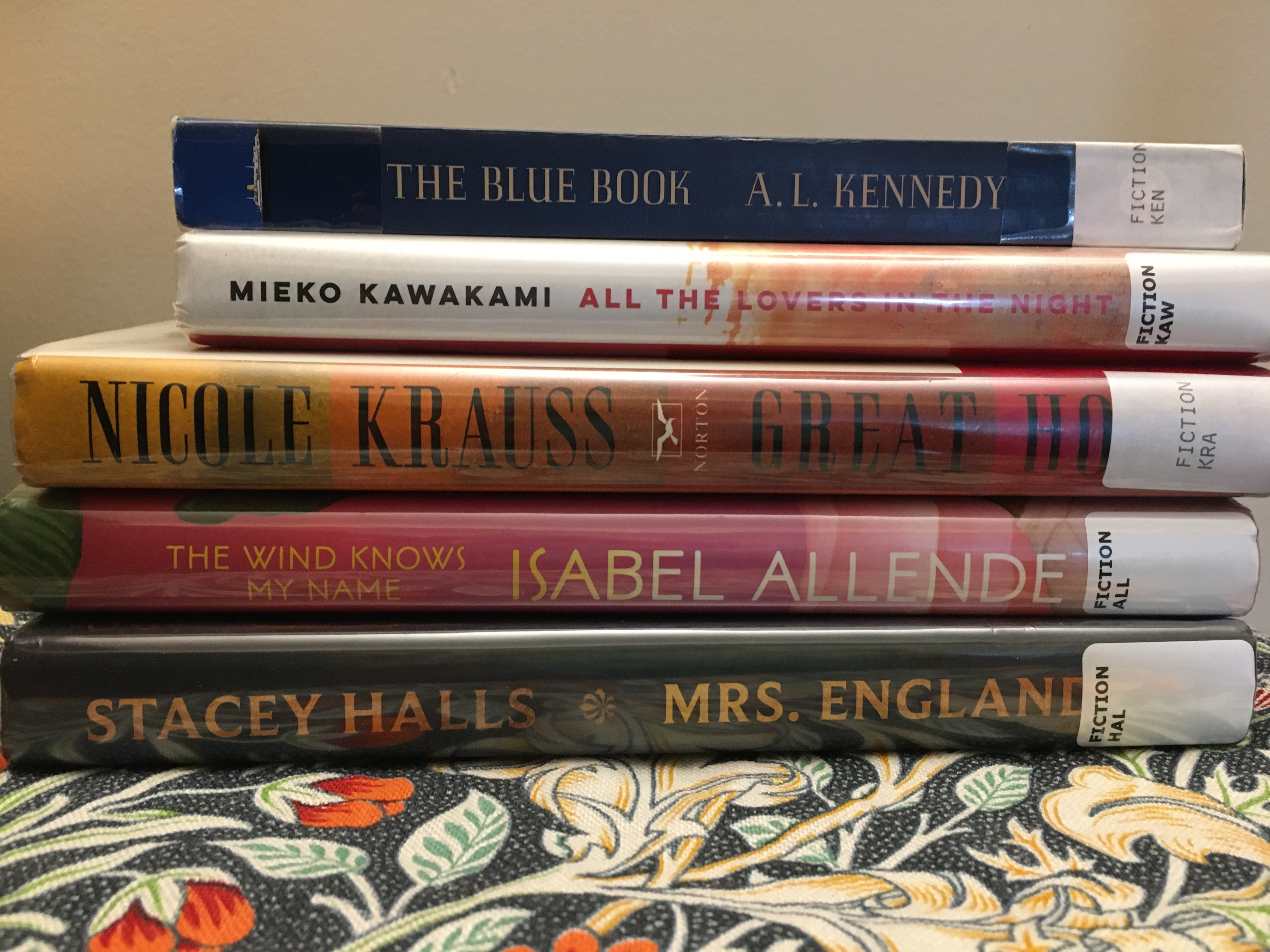

I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir’s Hotel Silence, since I liked Butterflies in November a lot. I hope to get through all the books in that stack before they come due—but I know I’m not the only reader who finds that their aspirations of this kind, and the pace of their library holds, can exceed their capacity!

I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir’s Hotel Silence, since I liked Butterflies in November a lot. I hope to get through all the books in that stack before they come due—but I know I’m not the only reader who finds that their aspirations of this kind, and the pace of their library holds, can exceed their capacity!

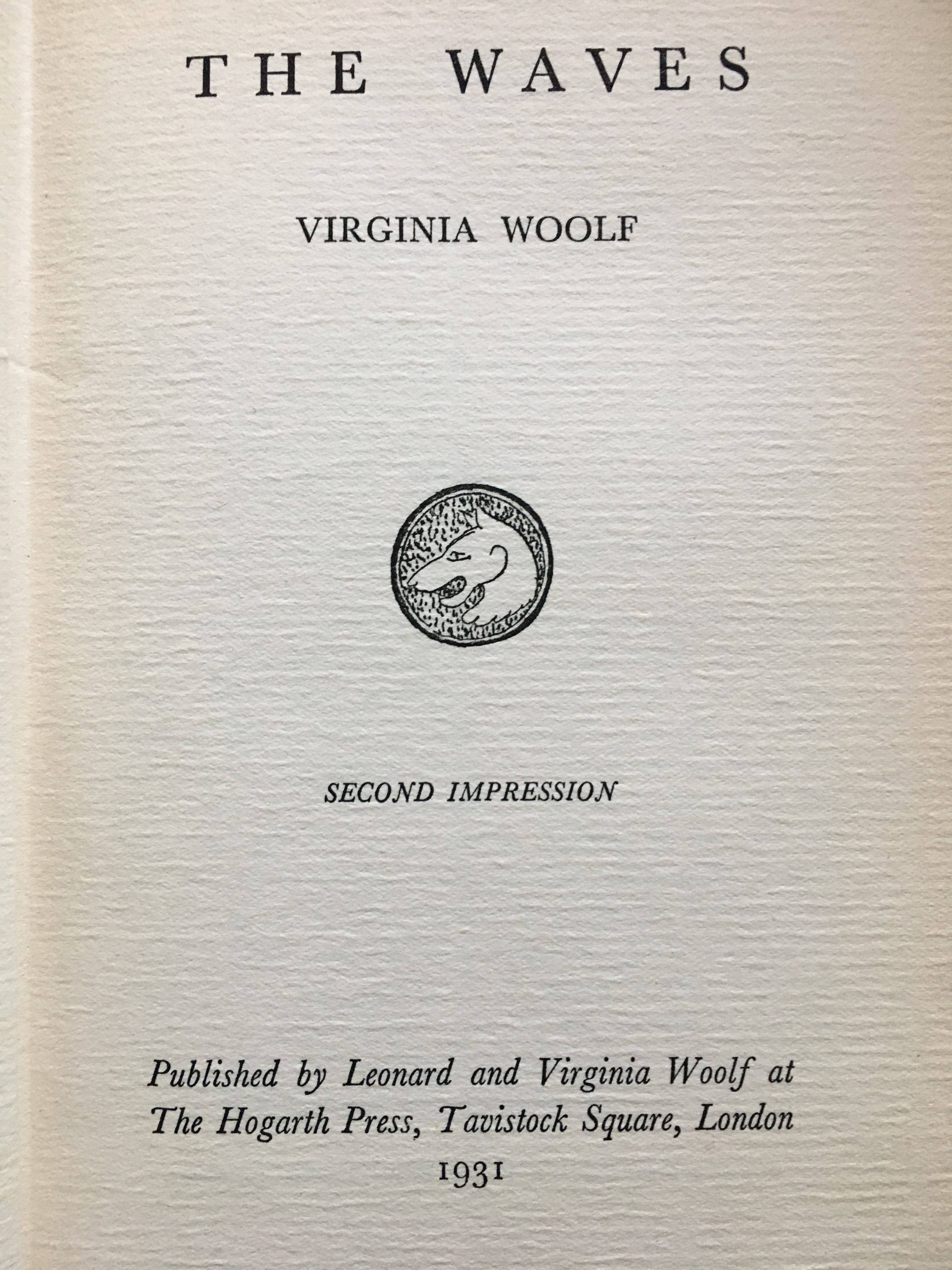

June began slowly, as a reading month anyway, as I was in Vancouver for the first 10 days of it and, as is pretty typical on these trips, I was too busy to settle down with a book. I did read about half of John Vaillant’s The Golden Spruce on the plane, and most of Donna Leon’s Drawing Conclusions while I was there (I borrowed it from my parents’ well-stocked mystery shelves but did not manage to finish it before I left). I’m definitely not complaining! It was a cheerful visit, made more so because Maddie was with me and I loved sharing my favorite people and places with her. Because we were also sharing a suitcase, I was also very restrained and did not buy any books while I was there. The only one I acquired was a very cool gift from my mother: a second impression of the first edition of The Waves

June began slowly, as a reading month anyway, as I was in Vancouver for the first 10 days of it and, as is pretty typical on these trips, I was too busy to settle down with a book. I did read about half of John Vaillant’s The Golden Spruce on the plane, and most of Donna Leon’s Drawing Conclusions while I was there (I borrowed it from my parents’ well-stocked mystery shelves but did not manage to finish it before I left). I’m definitely not complaining! It was a cheerful visit, made more so because Maddie was with me and I loved sharing my favorite people and places with her. Because we were also sharing a suitcase, I was also very restrained and did not buy any books while I was there. The only one I acquired was a very cool gift from my mother: a second impression of the first edition of The Waves , from the Hogarth Press.

, from the Hogarth Press.  , that while all of its detail about the history and processes of the lumber industry in BC were interesting enough, the book also gave the impression of a single man’s story elaborated or built up with background and contexts until it made a large enough whole. Sometimes I just wanted to get on with the actual events!

, that while all of its detail about the history and processes of the lumber industry in BC were interesting enough, the book also gave the impression of a single man’s story elaborated or built up with background and contexts until it made a large enough whole. Sometimes I just wanted to get on with the actual events!

Book blogging was easier, somehow, when I just wrote up every book I read as soon as I finished it. I was so much busier in other respects when I adopted that habit: looking back, I have now idea how I found the time for it. But one plausible theory is that I saved a lot of time not dithering about blogging! Just do it – good advice for so many things, including writing.

Book blogging was easier, somehow, when I just wrote up every book I read as soon as I finished it. I was so much busier in other respects when I adopted that habit: looking back, I have now idea how I found the time for it. But one plausible theory is that I saved a lot of time not dithering about blogging! Just do it – good advice for so many things, including writing. The novel’s non-stop melodrama is in service of a worldview, or an idea about human desires and instincts. I think possibly this sentence is key: “The door of terror opened over the black chasm of sex, love even unto death, destruction for fuller possession.” I hope the One Bright Pod folks (whose fault it is that I read this) will tell me if there is some kind of link to D. H. Lawrence here: it seems so to me, but I don’t know Lawrence well enough to be sure. I also hope they talk about what trains signify and how they are used in the novel. They are clearly (I think) symbols of modernity, but there is a lot more going on with them, especially the engine personified by one of the characters as a woman (“she” is perhaps his most genuinely caring relationship). Once I’d

The novel’s non-stop melodrama is in service of a worldview, or an idea about human desires and instincts. I think possibly this sentence is key: “The door of terror opened over the black chasm of sex, love even unto death, destruction for fuller possession.” I hope the One Bright Pod folks (whose fault it is that I read this) will tell me if there is some kind of link to D. H. Lawrence here: it seems so to me, but I don’t know Lawrence well enough to be sure. I also hope they talk about what trains signify and how they are used in the novel. They are clearly (I think) symbols of modernity, but there is a lot more going on with them, especially the engine personified by one of the characters as a woman (“she” is perhaps his most genuinely caring relationship). Once I’d  The other three books I’ve finished are Mollie Keane’s Good Behaviour (didn’t much like it, though I could see how skillful it is), Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans (found it boring even though I knew he was doing his withholding / unreliable narrator trick again so I knew that if I only understood what lay beneath the boring layer, it would be much more interesting – this is a risk he takes repeatedly, as I discussed in

The other three books I’ve finished are Mollie Keane’s Good Behaviour (didn’t much like it, though I could see how skillful it is), Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans (found it boring even though I knew he was doing his withholding / unreliable narrator trick again so I knew that if I only understood what lay beneath the boring layer, it would be much more interesting – this is a risk he takes repeatedly, as I discussed in  What’s next, you wonder? Maybe Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts, which I picked up recently with a birthday gift card (thank you!), or something from my miscellaneous stack of library books. Living so close to the public library has made me pretty casual about taking things out that I may or may not commit to reading: I like having options! (If there’s anything there you think I should definitely try, let me know.) I also have Cold Comfort Farm to hand, which was my ‘Independent Bookstore Day’ treat – but I’m saving it to read on the plane when I go to Vancouver in a couple of weeks.

What’s next, you wonder? Maybe Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts, which I picked up recently with a birthday gift card (thank you!), or something from my miscellaneous stack of library books. Living so close to the public library has made me pretty casual about taking things out that I may or may not commit to reading: I like having options! (If there’s anything there you think I should definitely try, let me know.) I also have Cold Comfort Farm to hand, which was my ‘Independent Bookstore Day’ treat – but I’m saving it to read on the plane when I go to Vancouver in a couple of weeks. April hasn’t been a bad month for reading, overall. I’ve already written up Dorothy B. Hughes’s

April hasn’t been a bad month for reading, overall. I’ve already written up Dorothy B. Hughes’s  I read Maylis De Kerangal’s Eastbound in one sitting, not just because it’s short but because it’s very suspenseful and I really wanted to find out what happened! I ended up thinking that the novel’s success in this respect worked against the quality of my reading of it, because I didn’t linger over the aspects of the novel that make it more than just a thriller. The story is very simple: a young Russian soldier on a train to Siberia decides to go AWOL and is helped in his attempted escape by another passenger, a young French woman. Will he succeed, or will he be discovered and pay the price? Anxious to know, I paid less attention than I should have to the descriptions of the landscape scrolling past them – though I did appreciate them, I didn’t really think about them, and a reread of the novel would probably show me more metaphorical and historical layers to the characters’ journey. Some other time, maybe, as I had to return my copy to the library! But even my brisk reading showed me why

I read Maylis De Kerangal’s Eastbound in one sitting, not just because it’s short but because it’s very suspenseful and I really wanted to find out what happened! I ended up thinking that the novel’s success in this respect worked against the quality of my reading of it, because I didn’t linger over the aspects of the novel that make it more than just a thriller. The story is very simple: a young Russian soldier on a train to Siberia decides to go AWOL and is helped in his attempted escape by another passenger, a young French woman. Will he succeed, or will he be discovered and pay the price? Anxious to know, I paid less attention than I should have to the descriptions of the landscape scrolling past them – though I did appreciate them, I didn’t really think about them, and a reread of the novel would probably show me more metaphorical and historical layers to the characters’ journey. Some other time, maybe, as I had to return my copy to the library! But even my brisk reading showed me why  My current reading is Shawna Lemay’s Apples on a Windowsill, which is (more or less) about still lifes as a genre, but which roams across a range of topics in a thoughtful and often beautifully meditative way. A sample:

My current reading is Shawna Lemay’s Apples on a Windowsill, which is (more or less) about still lifes as a genre, but which roams across a range of topics in a thoughtful and often beautifully meditative way. A sample:

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place.

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place. I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite:

I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite: I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer.

I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer. Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his

Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his  I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps

I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps  My last two reads of this summer were Yiyun Li’s The Book of Goose and Ann Patchett’s Tom Lake. For me, one was a hit, the other a miss.

My last two reads of this summer were Yiyun Li’s The Book of Goose and Ann Patchett’s Tom Lake. For me, one was a hit, the other a miss. Another warning sign should have been how many reviews (including some quoted in the pages of “Praise for The Book of Goose” that lead off my paperback edition) compare it to Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. I am cynical about these tendentious excerpts so I don’t pay very close attention to them when I’m making up my mind about what to read. Maybe I should change my habits! Because the Ferrante comparison occurred to me not too far into Li’s novel, and not for good reasons. (

Another warning sign should have been how many reviews (including some quoted in the pages of “Praise for The Book of Goose” that lead off my paperback edition) compare it to Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. I am cynical about these tendentious excerpts so I don’t pay very close attention to them when I’m making up my mind about what to read. Maybe I should change my habits! Because the Ferrante comparison occurred to me not too far into Li’s novel, and not for good reasons. ( Tom Lake was a much more enjoyable read, although like the other Patchett novels I have read recently, it didn’t seem to me to go particularly deep. Still, there was something really satisfying about it: I liked it a lot more than either

Tom Lake was a much more enjoyable read, although like the other Patchett novels I have read recently, it didn’t seem to me to go particularly deep. Still, there was something really satisfying about it: I liked it a lot more than either  If you’re a friend of mine on social media, it won’t surprise you that Hernan Diaz’s Trust is the first one. It is an inarguably ingenious novel, but I thought (and the other members of my book club agreed) that the payoff for its ingenuity in the second half wasn’t enough to make up for the extraordinary, if self-conscious, dullness of the first half. Even a novel that can only really light up on a second reading can (and, arguably, should) generate some excitement the first time through. For me, a case in point would be

If you’re a friend of mine on social media, it won’t surprise you that Hernan Diaz’s Trust is the first one. It is an inarguably ingenious novel, but I thought (and the other members of my book club agreed) that the payoff for its ingenuity in the second half wasn’t enough to make up for the extraordinary, if self-conscious, dullness of the first half. Even a novel that can only really light up on a second reading can (and, arguably, should) generate some excitement the first time through. For me, a case in point would be  I picked up Daniel Mason’s The Winter Soldier because I’m writing up his latest novel, North Woods, for the TLS and it’s good enough that I wanted to read more by him. The Winter Soldier is quite unlike North Woods, mostly in ways that favor the newer novel—which suggests Mason is getting better at his craft! The Winter Soldier (2018) is a good old-fashioned historical novel. It is packed with concrete details that make the time and place of its action vivid in the way I want historical fiction to be vivid. It takes place mostly in a remote field hospital in the Carpathian mountains during WWI; its protagonist, Lucius Krzelewski, is a medical student rapidly converted to a doctor to serve the desperate needs of the Austro-Hungarian army. His time at the hospital is full of harrowing incidents; through them runs his growing interest in an illness that eludes physical diagnosis and treatment—what today we would call PTSD. There are chaotic battle scenes and idyllic interludes; there’s a love story as well. It’s good! It really immerses you in its world, and (unlike Trust!) makes you care about its characters. I ended it not really sure it was about anything more than that. Novels don’t need to be, of course, though the best ones are. Still, I liked it enough that I will probably also look up Mason’s other novels, starting with The Piano Tuner. North Woods is a lot smarter and more subtle, though. (I am not sure it’s entirely successful: in my review, I will say more about that, when I figure out how to!)

I picked up Daniel Mason’s The Winter Soldier because I’m writing up his latest novel, North Woods, for the TLS and it’s good enough that I wanted to read more by him. The Winter Soldier is quite unlike North Woods, mostly in ways that favor the newer novel—which suggests Mason is getting better at his craft! The Winter Soldier (2018) is a good old-fashioned historical novel. It is packed with concrete details that make the time and place of its action vivid in the way I want historical fiction to be vivid. It takes place mostly in a remote field hospital in the Carpathian mountains during WWI; its protagonist, Lucius Krzelewski, is a medical student rapidly converted to a doctor to serve the desperate needs of the Austro-Hungarian army. His time at the hospital is full of harrowing incidents; through them runs his growing interest in an illness that eludes physical diagnosis and treatment—what today we would call PTSD. There are chaotic battle scenes and idyllic interludes; there’s a love story as well. It’s good! It really immerses you in its world, and (unlike Trust!) makes you care about its characters. I ended it not really sure it was about anything more than that. Novels don’t need to be, of course, though the best ones are. Still, I liked it enough that I will probably also look up Mason’s other novels, starting with The Piano Tuner. North Woods is a lot smarter and more subtle, though. (I am not sure it’s entirely successful: in my review, I will say more about that, when I figure out how to!) And then there’s Claudia Piñeiro’s Betty Boo, which I found a really satisfying combination of smart plotting, thoughtful storytelling, and ideas that matter. In some ways it is less ambitious than the other two novels: it is structured more or less conventionally as a crime novel, and there aren’t really any narrative tricks to it, unless you count the sections that are ostensibly written by the protagonist, Nurit Iscar, about its central murder case. Iscar is a crime novelist who has had a professional setback (a crushing review of her foray into romantic fiction) and is currently getting by as a ghost writer. A contact at a major newspaper asks her to write some articles about a murder from a less journalistic and more contemplative perspective; in aid of this mission, she moves into the gated community where the victim lived and died. She ends up collaborating with the reporters on the crime beat as they investigate the death and discover that it is a part of a larger and more sinister operation—about which, of course, I will not give you any details here! Betty Boo is an unusual book: it doesn’t read quite like a “genre” mystery, as it is at least as interested in Nurit’s life and especially her relationships, with her close women friends and her lovers, as it is in its crime story. Also, Betty Boo is about crime, reporting, and fiction as themes, though its attention to these issues is integrated into the storytelling so that it never really feels metafictional—unlike Trust, which is all gimmick and so no substance, Betty Boo seems committed to the value and possibility of substance, even as Piñeiro provokes us to think about the obstacles we face in achieving it, in writing or in life, especially now that the news as a vehicle for both information and storytelling has become so degraded. I appreciated how original Betty Boo felt, and how genuinely interesting it was: I haven’t read another writer who does quite what Piñeiro does, in it or, for that matter, in Elena Knows. Of the three novels I read recently, this is the one I’m most likely to recommend to others, and I’m definitely going to read more of Piñeiro’s fiction, probably starting with A Little Luck, when I can get my hands on it.

And then there’s Claudia Piñeiro’s Betty Boo, which I found a really satisfying combination of smart plotting, thoughtful storytelling, and ideas that matter. In some ways it is less ambitious than the other two novels: it is structured more or less conventionally as a crime novel, and there aren’t really any narrative tricks to it, unless you count the sections that are ostensibly written by the protagonist, Nurit Iscar, about its central murder case. Iscar is a crime novelist who has had a professional setback (a crushing review of her foray into romantic fiction) and is currently getting by as a ghost writer. A contact at a major newspaper asks her to write some articles about a murder from a less journalistic and more contemplative perspective; in aid of this mission, she moves into the gated community where the victim lived and died. She ends up collaborating with the reporters on the crime beat as they investigate the death and discover that it is a part of a larger and more sinister operation—about which, of course, I will not give you any details here! Betty Boo is an unusual book: it doesn’t read quite like a “genre” mystery, as it is at least as interested in Nurit’s life and especially her relationships, with her close women friends and her lovers, as it is in its crime story. Also, Betty Boo is about crime, reporting, and fiction as themes, though its attention to these issues is integrated into the storytelling so that it never really feels metafictional—unlike Trust, which is all gimmick and so no substance, Betty Boo seems committed to the value and possibility of substance, even as Piñeiro provokes us to think about the obstacles we face in achieving it, in writing or in life, especially now that the news as a vehicle for both information and storytelling has become so degraded. I appreciated how original Betty Boo felt, and how genuinely interesting it was: I haven’t read another writer who does quite what Piñeiro does, in it or, for that matter, in Elena Knows. Of the three novels I read recently, this is the one I’m most likely to recommend to others, and I’m definitely going to read more of Piñeiro’s fiction, probably starting with A Little Luck, when I can get my hands on it. April comes and April goes, whether you want her to or not. In the teaching term, it is always a blur of a month—a bit out of control, like rolling down a hill. I used to welcome the feeling—the exhilaration of finishing up, the anticipation of summer—but this year it is just one more reminder of how relentlessly, and how strangely, time passes.

April comes and April goes, whether you want her to or not. In the teaching term, it is always a blur of a month—a bit out of control, like rolling down a hill. I used to welcome the feeling—the exhilaration of finishing up, the anticipation of summer—but this year it is just one more reminder of how relentlessly, and how strangely, time passes.

The other books I read all of in April (I’m assuming I won’t finish another one by Sunday) were Elspeth Barker’s O, Caledonia and Martin Riker’s The Guest Lecture. It’s hard to imagine two books with less in common! I enjoyed O, Caledonia a lot, although it is strange and wild and—I thought—a bit random, almost artless: as I read it, I was often surprised, even confused, by it, uncertain why this was what was happening or this particular detail was in it. Yet it felt unified, nonetheless: maybe that strangeness itself unifies it! Its fierce protagonist Janet takes the “not like other girls” trope to an extreme: she’s equal parts compelling and appalling. It has something of the flavor of We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

The other books I read all of in April (I’m assuming I won’t finish another one by Sunday) were Elspeth Barker’s O, Caledonia and Martin Riker’s The Guest Lecture. It’s hard to imagine two books with less in common! I enjoyed O, Caledonia a lot, although it is strange and wild and—I thought—a bit random, almost artless: as I read it, I was often surprised, even confused, by it, uncertain why this was what was happening or this particular detail was in it. Yet it felt unified, nonetheless: maybe that strangeness itself unifies it! Its fierce protagonist Janet takes the “not like other girls” trope to an extreme: she’s equal parts compelling and appalling. It has something of the flavor of We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

March was a rough month. For one thing, I had more academic integrity hearings stemming from a single assignment than I’ve ever had in one term. It was an exceptionally disheartening experience, especially given the lengths I have gone to in my introductory class to reduce the risk for students of just trying to do the work for themselves: this is the class in which I’m using specifications grading, meaning there is really no risk involved. As I plaintively reminded the class as it became clear just how widespread the problem was, the class is designed to make it safe to be wrong, safe to be confused, safe to be learning. But if you don’t actually do your own writing, you strip the whole process of its meaning. Plus (as I pointed out to many students in the actual hearings), if your uncertainty leads you to copying other people’s writing, you will never build your own skills and your own confidence: you will never find out that you can in fact do the work, and get better at it.

March was a rough month. For one thing, I had more academic integrity hearings stemming from a single assignment than I’ve ever had in one term. It was an exceptionally disheartening experience, especially given the lengths I have gone to in my introductory class to reduce the risk for students of just trying to do the work for themselves: this is the class in which I’m using specifications grading, meaning there is really no risk involved. As I plaintively reminded the class as it became clear just how widespread the problem was, the class is designed to make it safe to be wrong, safe to be confused, safe to be learning. But if you don’t actually do your own writing, you strip the whole process of its meaning. Plus (as I pointed out to many students in the actual hearings), if your uncertainty leads you to copying other people’s writing, you will never build your own skills and your own confidence: you will never find out that you can in fact do the work, and get better at it.

Easily the best novel I read in March was Claudia Piñeiro’s Elena Knows. This was recommended to me last year when I was (as I so often am) casting about for new ideas for my two mystery fiction courses. I started it then but had to abandon it, as a novel about suicide and a mother’s grief was not an experience I could bear. I kept it on my mental TBR, though, and I’m glad I tried again, because it really is exceptional: slight but fierce and complex, with its overlapping interests in disability, ageism, misogyny, and autonomy. I think it would be a really interesting book to read in my course on Women & Detective Fiction, even though in many ways it is not really a mystery. It is certainly about a crime – or, crimes, if you think socially and systemically – and there is an investigation, even if there isn’t a detective, or evidence, or any of the other conventional elements.

Easily the best novel I read in March was Claudia Piñeiro’s Elena Knows. This was recommended to me last year when I was (as I so often am) casting about for new ideas for my two mystery fiction courses. I started it then but had to abandon it, as a novel about suicide and a mother’s grief was not an experience I could bear. I kept it on my mental TBR, though, and I’m glad I tried again, because it really is exceptional: slight but fierce and complex, with its overlapping interests in disability, ageism, misogyny, and autonomy. I think it would be a really interesting book to read in my course on Women & Detective Fiction, even though in many ways it is not really a mystery. It is certainly about a crime – or, crimes, if you think socially and systemically – and there is an investigation, even if there isn’t a detective, or evidence, or any of the other conventional elements.

After I finished Gwendoline Riley’s My Phantoms, I commented on Twitter that I was finding cold, meticulous novels wearing and asked for recommendations of good, recent warm-hearted fiction. Along with the understandable and spot-on nods to writers I already know well (such as Barbara Pym and Anne Tyler), I got a lot of good tips, which I am still working through. Here are the ones I have read so far. I have to say that while they have all been fine, none of them really got much traction with me: I don’t think it is necessarily the case that “warm-hearted” means lightweight, but that’s how these mostly felt. I don’t think I will remember much about them. The exception so far is

After I finished Gwendoline Riley’s My Phantoms, I commented on Twitter that I was finding cold, meticulous novels wearing and asked for recommendations of good, recent warm-hearted fiction. Along with the understandable and spot-on nods to writers I already know well (such as Barbara Pym and Anne Tyler), I got a lot of good tips, which I am still working through. Here are the ones I have read so far. I have to say that while they have all been fine, none of them really got much traction with me: I don’t think it is necessarily the case that “warm-hearted” means lightweight, but that’s how these mostly felt. I don’t think I will remember much about them. The exception so far is

Elizabeth McCracken, The Hero of This Book. I liked this one quite a lot except for the uneasiness it created in me about what kind of book it is, exactly. I realize that is one of the main points of the book, to destabilize assumptions about what constitutes a memoir or a novel or autofiction or whatever. I understood this because McCracken makes rather a lot of noise about it: “What’s the difference between a novel and a memoir?” she asks; “I couldn’t tell you. Permission to lie; permission to cast aside worries about plausibility.” “It’s not a made-up place,” she says about a trip she and her mother make to the theater (or do they?),

Elizabeth McCracken, The Hero of This Book. I liked this one quite a lot except for the uneasiness it created in me about what kind of book it is, exactly. I realize that is one of the main points of the book, to destabilize assumptions about what constitutes a memoir or a novel or autofiction or whatever. I understood this because McCracken makes rather a lot of noise about it: “What’s the difference between a novel and a memoir?” she asks; “I couldn’t tell you. Permission to lie; permission to cast aside worries about plausibility.” “It’s not a made-up place,” she says about a trip she and her mother make to the theater (or do they?),

I read 8.5 new books this month and blogged about . . . none of them? Hmmm. I’m honestly not sure if the fault is mine or theirs. Not one of them lit me up, but that didn’t used to keep me from rambling on about a book! So maybe the problem is what I’m bringing to them as a reader these days—but if so, does that mean my reports on them are unreliable? Who knows? As always, all we can really talk about is our experience of a book.

I read 8.5 new books this month and blogged about . . . none of them? Hmmm. I’m honestly not sure if the fault is mine or theirs. Not one of them lit me up, but that didn’t used to keep me from rambling on about a book! So maybe the problem is what I’m bringing to them as a reader these days—but if so, does that mean my reports on them are unreliable? Who knows? As always, all we can really talk about is our experience of a book.

Kate Clayborn, Georgie All Along. The long-awaited (well, for at least a year anyway) new romance novel from my favorite contemporary romance author—that is, my favorite author of contemporary romances. I enjoyed it fine but it seemed too much like her other novels and not as good as the earliest ones. They are packed full (almost too full) of details, especially of the kind I learned to call “neepery” (whether it’s metallurgy or home restoration or photography, Clayborn is good at conveying the texture and fascination of people’s interests); they are also quite emotionally intense. This one included some of the same kind of stuff but in a less engrossing way; the characters also seemed too conspicuously constructed, like concepts that didn’t 100% come to life. But I might change my mind on rereading: I had a similar reaction to her previous one, Love At First, but liked it quite a bit more when I went back to it more recently.

Kate Clayborn, Georgie All Along. The long-awaited (well, for at least a year anyway) new romance novel from my favorite contemporary romance author—that is, my favorite author of contemporary romances. I enjoyed it fine but it seemed too much like her other novels and not as good as the earliest ones. They are packed full (almost too full) of details, especially of the kind I learned to call “neepery” (whether it’s metallurgy or home restoration or photography, Clayborn is good at conveying the texture and fascination of people’s interests); they are also quite emotionally intense. This one included some of the same kind of stuff but in a less engrossing way; the characters also seemed too conspicuously constructed, like concepts that didn’t 100% come to life. But I might change my mind on rereading: I had a similar reaction to her previous one, Love At First, but liked it quite a bit more when I went back to it more recently. Sarah Winman, When God Was a Rabbit. I happened across this one at a thrift store and grabbed it because I liked Still Life so much. It is not as good as Still Life but it kept my interest from start to finish, which these days is saying something. The narrator’s voice in particular is effective, and I also appreciated the novel’s journey across key events in recent decades, landing on them as events in specific people’s lives. This includes 9/11; I learned from the author’s note that this was a controversial aspect of the novel, which didn’t really make any sense to me.

Sarah Winman, When God Was a Rabbit. I happened across this one at a thrift store and grabbed it because I liked Still Life so much. It is not as good as Still Life but it kept my interest from start to finish, which these days is saying something. The narrator’s voice in particular is effective, and I also appreciated the novel’s journey across key events in recent decades, landing on them as events in specific people’s lives. This includes 9/11; I learned from the author’s note that this was a controversial aspect of the novel, which didn’t really make any sense to me. Gwendoline Riley, My Phantoms. I didn’t enjoy this at all. I could tell it was “well written,” meaning it has crisp, often resonant sentences and is constructed with conspicuous care. The narrator is unpleasant; the relationship she has with her mother is worse than that. I wasn’t sure what the point of the exercise was supposed to be: it takes about 2 pages to get the gist of how uncomfortable it is all going to be and then it’s just discomfort and nastiness, with a bit of pathos thrown in, for another 150 pages. OK, I exaggerate slightly, but I want this post to serve as a cautionary tale for me: beware Twitter enthusiasm! I have learned not to rush off after whatever mid-century middle European novel from NYRB Classics is currently getting all the buzz, because it will probably just sit unread on my shelves along with Sybille Bedford’s A Legacy. For people who like these kinds of things, these kinds of things are great! (And it’s true that sometimes, a bit to my own surprise, I like them too.) But cold, clinical, forensically observant narrators are not my thing. Gorgeous cover on this edition, though!

Gwendoline Riley, My Phantoms. I didn’t enjoy this at all. I could tell it was “well written,” meaning it has crisp, often resonant sentences and is constructed with conspicuous care. The narrator is unpleasant; the relationship she has with her mother is worse than that. I wasn’t sure what the point of the exercise was supposed to be: it takes about 2 pages to get the gist of how uncomfortable it is all going to be and then it’s just discomfort and nastiness, with a bit of pathos thrown in, for another 150 pages. OK, I exaggerate slightly, but I want this post to serve as a cautionary tale for me: beware Twitter enthusiasm! I have learned not to rush off after whatever mid-century middle European novel from NYRB Classics is currently getting all the buzz, because it will probably just sit unread on my shelves along with Sybille Bedford’s A Legacy. For people who like these kinds of things, these kinds of things are great! (And it’s true that sometimes, a bit to my own surprise, I like them too.) But cold, clinical, forensically observant narrators are not my thing. Gorgeous cover on this edition, though!