I’ve been meaning to catch up on my recent reading for weeks now: it has been a month since I wrote up Sarah Moss’s Ripeness, and it isn’t as if I haven’t read anything since then! The problem (for posting, anyway) is that I haven’t read anything that made me want to write about it. I didn’t used to use that as an excuse: I just wrote up everything! And in the process I often found I did have things to say. Let’s see if that happens this time as I go through my recent reading.

I’ve been meaning to catch up on my recent reading for weeks now: it has been a month since I wrote up Sarah Moss’s Ripeness, and it isn’t as if I haven’t read anything since then! The problem (for posting, anyway) is that I haven’t read anything that made me want to write about it. I didn’t used to use that as an excuse: I just wrote up everything! And in the process I often found I did have things to say. Let’s see if that happens this time as I go through my recent reading.

I had put in some holds on some lighter reading options that all seemed to come in at once. The timing wasn’t bad, as I was too distracted by the rush to get the term underway when the lockout ended to dig in to anything very demanding. Even as diversions, though, none of these were particularly satisfying reads: Katherine Center’s The Love-Haters seemed contrived to me; Beth O’Leary’s Swept Away was (as Miss Bates had already warned me in her review) good until it wasn’t; Linda Holmes’s Back After This wasn’t terrible but it also seemed contrived—a reaction that I realize may be less about the books than about my chafing for some reason at the necessary contrivance of romance plots. But I’m rereading Holmes’s Evvie Drake Starts Over now and liking it as much as I did before, so maybe it is at least partly the books’ fault that they seemed so formulaic.

I read Patrick Modiano’s So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighbourhood for my book club, which met to discuss it on Wednesday. It was the first Modiano any of us had read, and we chose it because we wanted to follow up Smilla’s Sense of Snow with something that offered a more literary twist on the mystery genre. So You Don’t Get Lost certainly does that—maybe, we thought, it goes (for our tastes) too far in the other direction: it is so far away from being plot-driven that, as any reader of the novel will know, following the plot is like pushing on a cloud. I think I would have found it annoying if the novel had been longer, but it’s novella-length, and once I realized all the noir premises and promises of the opening were going to remain unfulfilled, I enjoyed just going where it took me. It is wonderfully atmospheric, and Modiano managed to keep me wondering about what had happened while also frustrating my curiosity at almost every turn. “In the end,” his narrator says, “we forget the details of our lives that embarrass us or are too painful. We just lie back and allow ourselves to float along calmly over the deep waters, with our eyes closed” —which is not a bad description of how I decided to read the book. I don’t think I want to read anything else by Modiano, though. For a better-informed commentary, read Tony’s post.

—which is not a bad description of how I decided to read the book. I don’t think I want to read anything else by Modiano, though. For a better-informed commentary, read Tony’s post.

I read Kate Cayley’s Property, which I thought was well written and artfully constructed but (again, for my taste) too much so, too deliberate, never gripping until its final sequence, which then annoyed me by being manipulative and melodramatic. Kerry liked it better than I did. I didn’t dislike it; I just never really wanted to pick it up again when I’d put it down, and I also kept forgetting which character was which, which in a fairly short book with a tight cast of characters seems like it might not be all my fault.

I read Lily King’s Heart the Lover because I’m reviewing it for the TLS, so you’ll have to wait to find out what I think about it! (I’m still figuring that out as I reread it, anyway: I can say that it is a book that has so far elicited a lot of equivocation from me!)

I am currently reading Tove Ditlevsen’s Copenhagen Trilogy. This too I am not eager to pick up again after I put it down, but when I do pick it up, I keep coming across hard-hitting gems of sentences (is that a mixed metaphor?) “Wherever you turn,” says narrator Tove, “you run up against your childhood and hurt yourself because it’s sharp-edged and hard, and stops only when it has torn you completely apart.” On the brink of youth,

Now the last remnants [of childhood] fall away from me like flakes of sun-scorched skin, and beneath looms an awkward, an impossible adult. I read in my poetry album while the night wanders past the window—and, unawares, my childhood falls silently to the bottom of my memory, that library of the soul from which I will draw knowledge and experience for the rest of my life.

It seems unfair to characterize as a “reading slump” a period that includes both this and (in its very different register) the Modiano, and yet that is how the past few weeks have felt. Good thing that today in class we began what will be nearly a month of work on David Copperfield! Dickens has rescued me before and already, six chapters in, I can tell that whether or not I read any other books in the next little while that excite me, he’s going to show me all over again what a great reading experience is like.

It seems unfair to characterize as a “reading slump” a period that includes both this and (in its very different register) the Modiano, and yet that is how the past few weeks have felt. Good thing that today in class we began what will be nearly a month of work on David Copperfield! Dickens has rescued me before and already, six chapters in, I can tell that whether or not I read any other books in the next little while that excite me, he’s going to show me all over again what a great reading experience is like.

I thought I had done very little reading in July, and I was prepared to defend myself: “

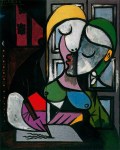

I thought I had done very little reading in July, and I was prepared to defend myself: “ The unexpected highlight was a very last minute choice: an interesting conversation with my lovely mom about A. S. Byatt convinced me I should reread the ‘Frederica quartet,’ but I felt too lackadaisical that night to jump right in so I plucked Byatt’s The Matisse Stories off the shelf on July 30 and finished it July 31. I’ve owned it for ages (I think it was a book sale find) but hadn’t gotten around to it. It turns out to be a really fascinating trio of stories all related (surprise! 🙂 ) in some way to paintings by Matisse, though in unpredictable ways. In the first one, a middle-aged woman reaches a breaking point at the salon and ends up absolutely trashing the place: I would never do such a thing to my nice stylist or the pleasant salon she co-owns, but there was something profoundly understandable about this woman’s rage. In the second, a self-absorbed, pretentious artist endlessly catered to (if silently criticized) by his deferential wife gets an unexpected come-uppance when it turns out their cleaning lady is the one whose wild artistic creations get noticed. The third turns on an accusation against a professor by a student who is clearly unwell; there’s a lot of thought-provoking discussion in it about art and standards, but what will stay with me is a stark moment of acknowledgment between two people who, it becomes clear, have both considered ending their lives:

The unexpected highlight was a very last minute choice: an interesting conversation with my lovely mom about A. S. Byatt convinced me I should reread the ‘Frederica quartet,’ but I felt too lackadaisical that night to jump right in so I plucked Byatt’s The Matisse Stories off the shelf on July 30 and finished it July 31. I’ve owned it for ages (I think it was a book sale find) but hadn’t gotten around to it. It turns out to be a really fascinating trio of stories all related (surprise! 🙂 ) in some way to paintings by Matisse, though in unpredictable ways. In the first one, a middle-aged woman reaches a breaking point at the salon and ends up absolutely trashing the place: I would never do such a thing to my nice stylist or the pleasant salon she co-owns, but there was something profoundly understandable about this woman’s rage. In the second, a self-absorbed, pretentious artist endlessly catered to (if silently criticized) by his deferential wife gets an unexpected come-uppance when it turns out their cleaning lady is the one whose wild artistic creations get noticed. The third turns on an accusation against a professor by a student who is clearly unwell; there’s a lot of thought-provoking discussion in it about art and standards, but what will stay with me is a stark moment of acknowledgment between two people who, it becomes clear, have both considered ending their lives: Nothing else I read made me think or feel as much as this little volume. I quite liked Ian Rankin’s Midnight and Blue; it has been especially fun watching Rankin push Rebus along through the years rather than preserving him in eternal crime-fighting youth. I also liked Kate Atkinson’s Death at the Sign of the Rook. I read Peter Hoeg’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow for my book club (I’m not considering this a re-read as it had been more than 30 years since my first go at it!). It starts out so strong! It goes so awry! It ends . . . with a parasitic worm? Really? Katerina Bivald’s The Murders in Great Diddling was mildly entertaining. Martha Wells’s All Systems Red—which I listened to as an audio book—was very entertaining and very short. Felix Francis’s The Syndicate was not very good: he took over his dad’s franchise and some of the results have been fine, but this one read like someone ticking off boxes.

Nothing else I read made me think or feel as much as this little volume. I quite liked Ian Rankin’s Midnight and Blue; it has been especially fun watching Rankin push Rebus along through the years rather than preserving him in eternal crime-fighting youth. I also liked Kate Atkinson’s Death at the Sign of the Rook. I read Peter Hoeg’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow for my book club (I’m not considering this a re-read as it had been more than 30 years since my first go at it!). It starts out so strong! It goes so awry! It ends . . . with a parasitic worm? Really? Katerina Bivald’s The Murders in Great Diddling was mildly entertaining. Martha Wells’s All Systems Red—which I listened to as an audio book—was very entertaining and very short. Felix Francis’s The Syndicate was not very good: he took over his dad’s franchise and some of the results have been fine, but this one read like someone ticking off boxes. The 0.5 is Ali Smith’s Gliff. I lost traction on it about half way through. Smith is a hit-or-miss author for me: I think she’s brilliant and absolutely love listening to her talk about her fiction, but the Seasonal Quartet are the only novels of hers that I have gotten along with well at all.

The 0.5 is Ali Smith’s Gliff. I lost traction on it about half way through. Smith is a hit-or-miss author for me: I think she’s brilliant and absolutely love listening to her talk about her fiction, but the Seasonal Quartet are the only novels of hers that I have gotten along with well at all. One of these was Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time, which I got interested in because Bradley was a brilliant guest on Backlisted. She was talking about Monkey King: Journey to the West—this was

One of these was Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time, which I got interested in because Bradley was a brilliant guest on Backlisted. She was talking about Monkey King: Journey to the West—this was

Anders Lustgarten’s Three Burials is also quite violent and action-driven, but underlying it is a less cynical or discouraging vision than I felt was at the core of A Line in the Sand. Its Thelma and Louise-style plot (a connection made explicit in the novel itself) focuses on Cherry, a nurse who happens upon the body of a murdered refugee (we already know him as Omar) on a British beach. Cherry is carrying a lot of grief and trauma, including her wrenching memories of the worst of the COVID pandemic (people currently downplaying the severity of the crisis and restricting access to the vaccines that have helped us get to a better place would benefit from the terse but powerful treatment it gets here). She is also grieving her son’s death by suicide, and the resemblance of the dead man to her son adds to her determination to somehow get his body to the young woman whose photo he was clutching when he died.

Anders Lustgarten’s Three Burials is also quite violent and action-driven, but underlying it is a less cynical or discouraging vision than I felt was at the core of A Line in the Sand. Its Thelma and Louise-style plot (a connection made explicit in the novel itself) focuses on Cherry, a nurse who happens upon the body of a murdered refugee (we already know him as Omar) on a British beach. Cherry is carrying a lot of grief and trauma, including her wrenching memories of the worst of the COVID pandemic (people currently downplaying the severity of the crisis and restricting access to the vaccines that have helped us get to a better place would benefit from the terse but powerful treatment it gets here). She is also grieving her son’s death by suicide, and the resemblance of the dead man to her son adds to her determination to somehow get his body to the young woman whose photo he was clutching when he died. My recent reading has not been particularly exhilarating, but most of it has been just fine: no duds, just no thrills.

My recent reading has not been particularly exhilarating, but most of it has been just fine: no duds, just no thrills. novel to spend the amount of time on it that I’d need to coax the students through its 450+ pages (more than two weeks, most likely). This is the conundrum of

novel to spend the amount of time on it that I’d need to coax the students through its 450+ pages (more than two weeks, most likely). This is the conundrum of  I got Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing from the library as soon as I had agreed to review her forthcoming novel The Book of Records, on the theory that it was probably a good idea to know something about the earlier one in case there were connections. It turns out there is one possibly important one, though I’m still figuring out exactly what it means: throughout Do Not Say We Have Nothing the characters are reading and writing and revising a narrative called the Book of Records! I actually owned a copy of Do Not Say We Have Nothing for years and put it in the donate pile eventually because for whatever reason I still hadn’t read it. I assigned a story by Thien in my first-year class this year that I thought was really good, so this had already piqued my interest in looking it up again. I had mixed feelings about it. I found it a bit rough or stilted stylistically and never really fell into it with full absorption, but it is packed with memorable elements and also with ideas. It tells harrowing stories about the Cultural Revolution in China and focuses through its musician characters on how or whether it is possible to hold on to whatever it is exactly that music and art mean in the face of such an onslaught on individuality and creativity. It invites us to think about storytelling as a means of survival, literal but also (in the broadest sense) cultural—this is where its Book of Records comes in, as the notebooks are cherished and preserved, often at great risk. I’m not very far into Thien’s new novel yet but it seems even more a novel of ideas, perhaps (we’ll see) too much so.

I got Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing from the library as soon as I had agreed to review her forthcoming novel The Book of Records, on the theory that it was probably a good idea to know something about the earlier one in case there were connections. It turns out there is one possibly important one, though I’m still figuring out exactly what it means: throughout Do Not Say We Have Nothing the characters are reading and writing and revising a narrative called the Book of Records! I actually owned a copy of Do Not Say We Have Nothing for years and put it in the donate pile eventually because for whatever reason I still hadn’t read it. I assigned a story by Thien in my first-year class this year that I thought was really good, so this had already piqued my interest in looking it up again. I had mixed feelings about it. I found it a bit rough or stilted stylistically and never really fell into it with full absorption, but it is packed with memorable elements and also with ideas. It tells harrowing stories about the Cultural Revolution in China and focuses through its musician characters on how or whether it is possible to hold on to whatever it is exactly that music and art mean in the face of such an onslaught on individuality and creativity. It invites us to think about storytelling as a means of survival, literal but also (in the broadest sense) cultural—this is where its Book of Records comes in, as the notebooks are cherished and preserved, often at great risk. I’m not very far into Thien’s new novel yet but it seems even more a novel of ideas, perhaps (we’ll see) too much so.

Last week in my classes it was Reading Week, a.k.a. the February “study break.” Although overall this term has not been nearly as hectic as last term, I was still grateful for the chance to ease up. Work is tiring. Winter is tiring. Grieving is tiring (yes, still). It doesn’t help that I continue to wake up a lot at night with shoulder pain, something I have been trying to fix for years now. (I am getting closer, I think! I am working with an orthopedist who seems pretty confident about what needs doing, although we are waiting for an ultrasound to confirm that the issue is my rotator cuff.)

Last week in my classes it was Reading Week, a.k.a. the February “study break.” Although overall this term has not been nearly as hectic as last term, I was still grateful for the chance to ease up. Work is tiring. Winter is tiring. Grieving is tiring (yes, still). It doesn’t help that I continue to wake up a lot at night with shoulder pain, something I have been trying to fix for years now. (I am getting closer, I think! I am working with an orthopedist who seems pretty confident about what needs doing, although we are waiting for an ultrasound to confirm that the issue is my rotator cuff.)

The one other book I got all the way through last week was actually an audiobook: my hold on Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain came in, and it proved truly gripping, surprisingly so given that I knew a fair amount about the whole story from various other sources (including the harrowing series Dopesick). I was so caught up in it that I spent longer hours than usual working on my current jigsaw puzzle—which I think contributed to my shoulder pain somehow, so that was a weird confluence as it had me thinking a lot about how tempting the promise of relief would be even for chronic pain as relatively mild as mine. Of course the whole story is also infuriating and outrageous and horrific, and perhaps it would have been more calming to stick to my usual, more benign, program of literary podcasts!

The one other book I got all the way through last week was actually an audiobook: my hold on Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain came in, and it proved truly gripping, surprisingly so given that I knew a fair amount about the whole story from various other sources (including the harrowing series Dopesick). I was so caught up in it that I spent longer hours than usual working on my current jigsaw puzzle—which I think contributed to my shoulder pain somehow, so that was a weird confluence as it had me thinking a lot about how tempting the promise of relief would be even for chronic pain as relatively mild as mine. Of course the whole story is also infuriating and outrageous and horrific, and perhaps it would have been more calming to stick to my usual, more benign, program of literary podcasts! and that timing may well have been the real reason for my middling reaction to it. So far I am enjoying it just fine; we’ll see if when I get to the end this time I feel like reading on in the series.

and that timing may well have been the real reason for my middling reaction to it. So far I am enjoying it just fine; we’ll see if when I get to the end this time I feel like reading on in the series. November wasn’t a bad reading month, considering how busy things were at work—and considering that “work” also means reading a fair amount, this time around including most of both Lady Audley’s Secret and Tess of the d’Urbervilles for 19thC Fiction and an array of short fiction and poetry for my intro class. (I have not managed to get back into a routine of posting about my teaching, but I would like to, so we’ll see what happens next term.)

November wasn’t a bad reading month, considering how busy things were at work—and considering that “work” also means reading a fair amount, this time around including most of both Lady Audley’s Secret and Tess of the d’Urbervilles for 19thC Fiction and an array of short fiction and poetry for my intro class. (I have not managed to get back into a routine of posting about my teaching, but I would like to, so we’ll see what happens next term.)

I felt the need for something cheering in the wake of The Election and landed on Connie Willis’s To Say Nothing of the Dog: it was a great choice, genuinely comic and warm-hearted but also endlessly clever. I had a lot of LOL moments over its characterizations of the Victorian period, and it is chock full of literary allusions, many of which I’m sure I didn’t catch. A lot of them are to Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers: who know that Gaudy Night would be one of its main running references. I liked it enough that I’ve put The Doomsday Book on my Christmas wish list, even though I don’t ordinarily gravitate towards this genre.

I felt the need for something cheering in the wake of The Election and landed on Connie Willis’s To Say Nothing of the Dog: it was a great choice, genuinely comic and warm-hearted but also endlessly clever. I had a lot of LOL moments over its characterizations of the Victorian period, and it is chock full of literary allusions, many of which I’m sure I didn’t catch. A lot of them are to Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers: who know that Gaudy Night would be one of its main running references. I liked it enough that I’ve put The Doomsday Book on my Christmas wish list, even though I don’t ordinarily gravitate towards this genre.

That said, I did quite enjoy Sara Levine’s Treasure Island!!!, which I picked up quite randomly at the library, mostly because it’s a Europa Edition but also because I vaguely recalled hearing good things about it online. It turned out to be a sharp and very funny send-up of the “great literature transformed my life” genre. Its narrator, whose life is in something of a shambles, reads Treasure Island and decides it offers her a template for turning things around. She adopts the novel’s “Core Values”—BOLDNESS, RESOLUTION, INDEPENDENCE, HORN-BLOWING—and applies them to her job (which, improbably and hilariously, is at a “pet hotel,” where clients sign out cats, dogs, rabbits, even goldfish), her boyfriend, and her family, with hilarious if also sometimes weirdly poignant results. I have such a love-hate relationship with books that purport to turn literature into self-help manuals that I relished the premise, but Levine uses it as a launching point for something much zanier than I could possibly have expected or can possibly summarize.

That said, I did quite enjoy Sara Levine’s Treasure Island!!!, which I picked up quite randomly at the library, mostly because it’s a Europa Edition but also because I vaguely recalled hearing good things about it online. It turned out to be a sharp and very funny send-up of the “great literature transformed my life” genre. Its narrator, whose life is in something of a shambles, reads Treasure Island and decides it offers her a template for turning things around. She adopts the novel’s “Core Values”—BOLDNESS, RESOLUTION, INDEPENDENCE, HORN-BLOWING—and applies them to her job (which, improbably and hilariously, is at a “pet hotel,” where clients sign out cats, dogs, rabbits, even goldfish), her boyfriend, and her family, with hilarious if also sometimes weirdly poignant results. I have such a love-hate relationship with books that purport to turn literature into self-help manuals that I relished the premise, but Levine uses it as a launching point for something much zanier than I could possibly have expected or can possibly summarize.

I’m trying to get back in the habit of writing up most (maybe not all) of the books I read so here we go with a quickish update on two novels that I recently finished.

I’m trying to get back in the habit of writing up most (maybe not all) of the books I read so here we go with a quickish update on two novels that I recently finished. In contrast, I had never heard of Jazmina Barrera’s Cross Stitch when I first spotted it in the bookstore a couple of months ago. Its title caught my eye because I do cross stitch myself, though it has been a while since I picked up any of my works in progress. (As my eyes age,

In contrast, I had never heard of Jazmina Barrera’s Cross Stitch when I first spotted it in the bookstore a couple of months ago. Its title caught my eye because I do cross stitch myself, though it has been a while since I picked up any of my works in progress. (As my eyes age,