The books by George Meredith in fine bindings line shelves. In the cupboard in a velvet case lies a drawing from the hand of another young lover, of a beautiful, large-eyed woman smiling a little, demure in her bonnet. Perhaps the artist is saying something that causes her to forget, for a moment, some bitter things she has learned. His enamored pencil does not catch, perhaps, a certain fated expression in here eyes. Kisses, from whomever, have left no imprints on the pretty lips. The young lover sees only his own kisses there. She will die soon. He will grow old. All this is more than a hundred years ago now. “Earthly love speedily becomes unmindful but love from heaven is mindful for ever more,” it was to have said on her tombstone. No one knows where her grave is now.

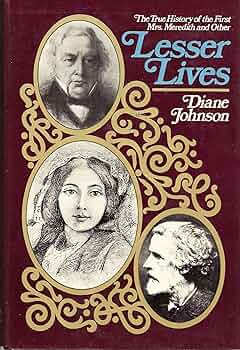

Reading Diane Johnson’s The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith (and Other Lesser Lives) is a disorienting experience. You think you know what you’re getting into when you begin—or I thought so, anyway. It is, after all, a period piece: first published in 1972, it is an exemplary contribution to the second-wave feminist project of literary reclamation, of resistance to the domination of men’s voices and men’s stories. Its tone, a blend of sass, defiance, and earnestness, reflects both the exuberance and the imperfections of that moment and that movement. Johnson’s project, in this context, initially sounds predictable, which is not to say it doesn’t also sound necessary and valuable, precisely as an act of resistance. “The life of Mary Ellen,” Johnson explains in her Preface,

is always treated, in a paragraph or a page, as an episode in the lives of [Thomas Love] Peacock or [George] Meredith. It was treated with a certain reserve in early biographies because it involves adultery and recrimination, and makes all the parties look ugly . . .

Mrs. Meredith’s life can be looked upon, of course, as an episode in the lives of Meredith or Peacock, but it cannot have seemed that way to her.

We are inundated today with stories of just such “lesser lives,” real and fictional, including novels about real but sidelined figures like The Paris Wife or ones like The Silence of the Girls that shift our point of view on “minor” characters in the great classical epics. When the subject is real person, the underlying point is always, as Johnson notes, that it is impossible, or should be, for someone not to be the main character in their own life. The ease with which, even today, we relegate women to secondary status, especially when they are connected in some way to—especially when they are wives of—“great men” continues to be shocking, or it should be. “Must it always be this way for women?” wonder the ghosts of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley early in Johnson’s book; “Here was one they thought might persevere in woman’s name. She had promise. She had courage.”

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says,

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says,

Mary Ellen, when she married George Meredith, had had a past already. Had already fallen in love, had already been married, had given birth to a child—all those life experiences that we normally expect to take place after the close of a Victorian novel, had taken place for Mary Ellen before the story with George began. The real drama of her life may have seemed to her to have nothing to do with George Meredith at all.

Every bit of information Johnson could scrounge up about Mary Ellen (including from a cache of letters she came across fortuitously in a box under a bed in a small house in Purley, Surrey) has gone into her recreation of that “real drama.” There is a lot of it! Mary Ellen’s father, the Romantic writer Thomas Love Peacock (he was a close friend of Shelley) thought girls should be free-spirited and educated and brought her up accordingly (he was in effect a single parent, as Mary Ellen’s mother “suffered from one of those long, household forms of madness, or severe neurosis, to which ladies in those days seemed especially prone). Peacock’s approach sounds delightful, and delightfully progressive:

Mary Ellen learned to read; she was allowed to read widely, pretty much what she wanted . . . unlike John Stuart [Mill], Mary Ellen was given fiction and poetry, to develop the heart as well as the head. And Mary Ellen messed around in boats, like a boy, and learned to row and sail and swim. She grew up to be a fearless horsewoman, so she was probably given a pony early.

And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.”

And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.”

The first “real drama” of Mary Ellen’s life was her first marriage, to a dashing sailor; he drowned, tragically, very soon after the wedding, but not too soon for Mary Ellen to have conceived a child. Then she met and married the aspiring novelist George Meredith, who was a few years her junior: apparently he always said she was 9 years older, but it was actually 6.5; he also called her “mad,” but in Johnson’s telling anyway, there is no supporting evidence for that claim. Things went well for the couple at first: they had literary ambition in common and eventually mutual projects, as well as children, but their happiness did not last. “The Historian cannot capture a process so slow as the death of a marriage,” Johnson (whose most famous novel today is called, as it happens, Le Divorce) remarks pensively:

He would need some other medium than the pen to do it with—perhaps one of those cameras that photograph the growing of a plant and the unfolding of its blossoms. With such a camera we could see the expressions change, telescoping the imperceptible changes of seven years into a few moments. We watch the passionate adoring glances glaze to cordiality, grow expressionless, contract with pain. The once ardent glances are now averted; fingers disentwine and are folded behind the separate backs. Backs are turned.

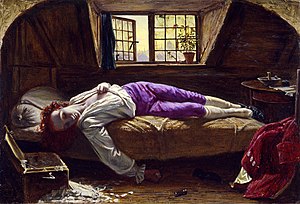

There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later ceramics collector—Henry Wallis. (Wallis’s most famous painting was and is ‘The Death of Chatterton,’ for which Meredith was the model.) They lived together adulterously and had a child; not long after, Mary Ellen died, leaving her still-doting father (and, presumably, her lover, but not her legal husband) bereft. Meredith continued to write novels; he also wrote a sonnet sequence, Modern Love, that chronicles the decay of a marriage much like his own. He achieved the lasting fame he always dreamed of and also made a second marriage with none of the turbulence of the first. Mary Ellen receded into obscurity, except, as Johnson emphasizes, through her pervasive presence in Meredith’s imagination and thus in his fiction.

There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later ceramics collector—Henry Wallis. (Wallis’s most famous painting was and is ‘The Death of Chatterton,’ for which Meredith was the model.) They lived together adulterously and had a child; not long after, Mary Ellen died, leaving her still-doting father (and, presumably, her lover, but not her legal husband) bereft. Meredith continued to write novels; he also wrote a sonnet sequence, Modern Love, that chronicles the decay of a marriage much like his own. He achieved the lasting fame he always dreamed of and also made a second marriage with none of the turbulence of the first. Mary Ellen receded into obscurity, except, as Johnson emphasizes, through her pervasive presence in Meredith’s imagination and thus in his fiction.

So far so good, and it is good, though there is possibly something reductive or dated in Johnson’s antagonistic vision of the times and people she writes about. It is hard to engage with the otherness of the past, especially when its values offend one’s own cherished principles; I struggle with this too, in my own thinking and writing and teaching about women in the 19th century, and I caution my students about it, urging them (for one thing) to avoid the anachronistic dichotomies often prompted by our ideas of what is or isn’t “feminist.” Johnson’s book, too, is now a historical document; that it sounds so “seventies” to me is not its fault, and it is overall a good thing that to some extent we can now take for granted the importance of “lesser lives” of all kinds, without insisting on it quite so, well, insistently.

The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write.

The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write.

She is also very interested in the reciprocal influence of genres on each other, especially of fictional conventions on the form of biographies, and of the impossibility in any case of simply recounting facts (even when there is abundant and unequivocal evidence of their outline, as there is not, for much of the story she is telling) without relying on qualities that are not strictly objective:

But what, anyway, are the ‘facts’ of a writer’s life? That George Meredith had an erring wife is a ‘fact,’ but for him, the existence of those fictional heroines Mrs. Mount and Mrs. Lovell is also ‘fact.’ The one is an external, the other an internal fact. The danger for the biographer, or critic, lies in mismatching external and interior equivalents. I suppose there is no safeguard against doing this except, one hopes, common sense and a (no doubt) suspect degree of empathy, especially with the ‘seamy’ side of human nature . . . Which returns me to my point: the biographer must be a historian, but also a novelist and a snoop.

At many points in The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith Johnson the novelist is clearly at work: she has to guess, imagine, speculate, embroider in order to fill in what we otherwise wouldn’t know. Does that mean that her biography (if that’s what it is) of Mary Ellen is not “true,” as the title proclaims it to be? Yes and no, I think she would readily say: it is as true as possible, factually, and where it cannot be true in that way, it is true to what her empathy reveals, or truthful about its status as empathetic guesswork.

The other aspect of The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith that I didn’t expect but really appreciated is pointed to by its subtitle, and Other Lesser Lives. More than just a memoir of Mary Ellen, Johnson’s book is a meditation on the whole concept of a “lesser life.” There is a polemical side to this, as I’ve already noted, a feminist advocacy for equalizing our attention, not looking only at, or caring only about, the great men of history:

Of course there is no way to really know the minds of Lizzie Rossetti, or the first Mrs. Milton, or all those silent Dickens children suffering the mad unkindness, the delirious pleasures of their terrifying father’s company . . . But we know a lesser life does not seem lesser to the person who leads one.

I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas,

I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas,

it is impossible to say. An old solicitor at the firm that always took care of Henry’s business remembers that he was a ‘tall thin man who always appeared to wear a long black cloak.’ Just before his twentieth birthday he entered the Bank of England and there worked with distinction, whatever working with distinction in a bank may involve [ha!], as Manager of the Dividend Department, for more than forty years and received a table service when he retired. He was happier than Papa, or Arthur [Mary Ellen’s son by George Meredith], or so it may be hoped, in that he married a pretty girl named Alice and had two children. Now they are all dead.

That’s an unexpected mic drop moment, there! It doesn’t mean (I feel certain) to suggest that none of what she’s just told us, or none of what these people did or were liked, matters, but it does abruptly remind us that in fact, all life stories end the same way. The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith ends on a similar note, more poignantly but still with a touch of the wit that makes the book such enjoyable reading:

Painters, writers, potters—all are dead. The greater lives along with the lesser. Things remain. Mary Ellen’s pink parasol lies in a trunk in a parlor in Purley [where Johnson found Mary Ellen’s letters]. Henry’s drawings lie in the boxroom upstairs. Henry’s little painting of George as Chatterton hangs in the Tate Gallery, properly humidified. The hair from Shelley’s head that Peacock gave to Henry, hair from the sacred hair of Shelley, Henry had put into a little ring, and people always kept it safe, but thieves broke into the house in Purley a year or two ago and stole it, and who can say where it is now? The turquoise vase from Rakka is safe in the museum; but I don’t know what happened to the majolica platter.

I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by the great discussion of it on Backlisted, which now I will listen to again.) It is that, but I was pleasantly surprised by how much more it is. I hope the others enjoy it as much as I did.

I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by the great discussion of it on Backlisted, which now I will listen to again.) It is that, but I was pleasantly surprised by how much more it is. I hope the others enjoy it as much as I did.

Now the pressing question is: do I want to read any of Meredith’s novels? or maybe Modern Love, which I read at least some of as a graduate student but haven’t looked at since? Before I read Johnson’s book, all that the name “George Meredith” readily brought to mind is Wilde’s famous quip “Meredith is a prose Browning, and so is Browning.” I love Browning, so maybe that’s a good omen? The Egoist seems to be generally considered Meredith’s best novel, but Johnson’s comments about Diana of the Crossways make it sound like the one I’d most like to try. Any Meredith lovers, or at least readers, out there who’d like to weigh in?

Money, money, money,

Money, money, money, But it matters (to me, at least) what those sentences are about, and also what they are for, and for me and most of the others in my book club, this was really the sticking point. What is it exactly that we are being invited to participate in when we read this novel? How far does “it’s for comic effect” excuse offering up the things Self says and does for our (presumed) entertainment? What kind of implied author (to let Amis himself temporarily off the hook) thinks that we will laugh, not just at how stupid Self is at the opera but at his attempts at rape? that we will be engaged and rewarded by a monologue that (however energetic and rhetorically ingenious) is relentlessly sexist and racist and bigoted? Again, we get it: John Self is an anti-hero, mercilessly exposed in all his vices; the novel is satirical, Rabelaisian, Swiftian, pick your poison. It is poisonous stuff, though, and—to bring Amis back into it—there’s such a sense of gleeful bad boy “look at me” about the whole thing, with all the metafictional cleverness deployed as back-up in case the whole “I’m only joking” excuse isn’t enough. That it is such a popular book among (as far we could tell, only) male readers is disconcerting: it’s as if an uncomfortable number of them enjoy a chance to vicariously indulge the kinds of demeaning, exploitative, offensive attitudes (towards women especially) that they know better than to express in propria persona. As we discussed, we have all had the tediously unpleasant experience, at one point of another, of calling out sexism in conversation with men we know, or in TV or movies we are watching with them, only to be dismissed or shut down or worse—often, again, with “it’s only a joke.” The feminist kill-joy is a role we’d rather not have to play, but the alternative is to shut up and take it. Between us, too, we’ve had enough of the other kinds of bad experiences John Self inflicts on the women in his life not to find his shamelessness about them entertaining. We don’t need any lessons in how bad this kind of s–t is, after all, so what social or moral or other revelation can possibly come our way from approaching them by way of John Self?

But it matters (to me, at least) what those sentences are about, and also what they are for, and for me and most of the others in my book club, this was really the sticking point. What is it exactly that we are being invited to participate in when we read this novel? How far does “it’s for comic effect” excuse offering up the things Self says and does for our (presumed) entertainment? What kind of implied author (to let Amis himself temporarily off the hook) thinks that we will laugh, not just at how stupid Self is at the opera but at his attempts at rape? that we will be engaged and rewarded by a monologue that (however energetic and rhetorically ingenious) is relentlessly sexist and racist and bigoted? Again, we get it: John Self is an anti-hero, mercilessly exposed in all his vices; the novel is satirical, Rabelaisian, Swiftian, pick your poison. It is poisonous stuff, though, and—to bring Amis back into it—there’s such a sense of gleeful bad boy “look at me” about the whole thing, with all the metafictional cleverness deployed as back-up in case the whole “I’m only joking” excuse isn’t enough. That it is such a popular book among (as far we could tell, only) male readers is disconcerting: it’s as if an uncomfortable number of them enjoy a chance to vicariously indulge the kinds of demeaning, exploitative, offensive attitudes (towards women especially) that they know better than to express in propria persona. As we discussed, we have all had the tediously unpleasant experience, at one point of another, of calling out sexism in conversation with men we know, or in TV or movies we are watching with them, only to be dismissed or shut down or worse—often, again, with “it’s only a joke.” The feminist kill-joy is a role we’d rather not have to play, but the alternative is to shut up and take it. Between us, too, we’ve had enough of the other kinds of bad experiences John Self inflicts on the women in his life not to find his shamelessness about them entertaining. We don’t need any lessons in how bad this kind of s–t is, after all, so what social or moral or other revelation can possibly come our way from approaching them by way of John Self? Our discussion wasn’t all negative. One member of the group noted that she felt John Self was a genuinely memorable, even iconic character, and we all grudgingly agreed that, hate him though we did, he was brilliantly executed: his voice (which is what Amis identified as the most important aspect of the novel, and fair enough) is distinctive and unforgettable. That we would like to forget it could, I suppose, be considered our problem, not the novel’s! Money also prompted a lot of discussion about the more general question of how far a novelist can or should go with an offensive character; we also considered why or whether Self is really so much worse than, say, the soulless ensemble of characters in Succession. We thought that Money would not have worked at all from the outside: what interest we took in Self, and any glimmering of sympathy we had for him, was entirely a product of our immersion in his point of view, which in turn became a test for us of Amis’s experiment, of how far he could go without losing us. We did all read to the end (though we mostly admitted having done some strategic skimming when it just got to be too much)—and our conversation was definitely lively. I don’t expect any of us will read anything else by Amis, though. (Years ago, I remembered, we read his father’s Ending Up, which we enjoyed thoroughly.)

Our discussion wasn’t all negative. One member of the group noted that she felt John Self was a genuinely memorable, even iconic character, and we all grudgingly agreed that, hate him though we did, he was brilliantly executed: his voice (which is what Amis identified as the most important aspect of the novel, and fair enough) is distinctive and unforgettable. That we would like to forget it could, I suppose, be considered our problem, not the novel’s! Money also prompted a lot of discussion about the more general question of how far a novelist can or should go with an offensive character; we also considered why or whether Self is really so much worse than, say, the soulless ensemble of characters in Succession. We thought that Money would not have worked at all from the outside: what interest we took in Self, and any glimmering of sympathy we had for him, was entirely a product of our immersion in his point of view, which in turn became a test for us of Amis’s experiment, of how far he could go without losing us. We did all read to the end (though we mostly admitted having done some strategic skimming when it just got to be too much)—and our conversation was definitely lively. I don’t expect any of us will read anything else by Amis, though. (Years ago, I remembered, we read his father’s Ending Up, which we enjoyed thoroughly.)

If my book club hadn’t settled on Sea of Tranquility for our next read, I don’t think I would have read it, not because I haven’t liked the other novels I’ve read by Emily St. John Mandel, because I’ve liked them just fine (

If my book club hadn’t settled on Sea of Tranquility for our next read, I don’t think I would have read it, not because I haven’t liked the other novels I’ve read by Emily St. John Mandel, because I’ve liked them just fine ( There’s real cleverness to the novel’s time-travel plot (though I don’t think these can ever be completely convincing), and a poignancy to the human story threaded through it, and the ongoing theme of pandemics created both menace in the moment and resonance for our moment.

There’s real cleverness to the novel’s time-travel plot (though I don’t think these can ever be completely convincing), and a poignancy to the human story threaded through it, and the ongoing theme of pandemics created both menace in the moment and resonance for our moment.  The other key idea in Sea of Tranquility seems to be “if you have the chance to save someone’s life, you should do it, rules or consequences be damned.” This hardly seems like a big idea—in fact, it seems trite, a point hardly worth making, a choice so obvious it hardly counts as heroism . . . except that for Gaspery, the rules are made by vast and powerful institutions and the consequences are literally historic. Does that make the “right” choice any less obvious? A different novelist, or a different kind of novel, would have made more of this, of how we weigh the kindness to others that defines our humanity against our own needs and vulnerabilities, and also against larger goals and values that might be incompatible with it and yet still, possibly, worth serving. “We should be kind,”

The other key idea in Sea of Tranquility seems to be “if you have the chance to save someone’s life, you should do it, rules or consequences be damned.” This hardly seems like a big idea—in fact, it seems trite, a point hardly worth making, a choice so obvious it hardly counts as heroism . . . except that for Gaspery, the rules are made by vast and powerful institutions and the consequences are literally historic. Does that make the “right” choice any less obvious? A different novelist, or a different kind of novel, would have made more of this, of how we weigh the kindness to others that defines our humanity against our own needs and vulnerabilities, and also against larger goals and values that might be incompatible with it and yet still, possibly, worth serving. “We should be kind,”

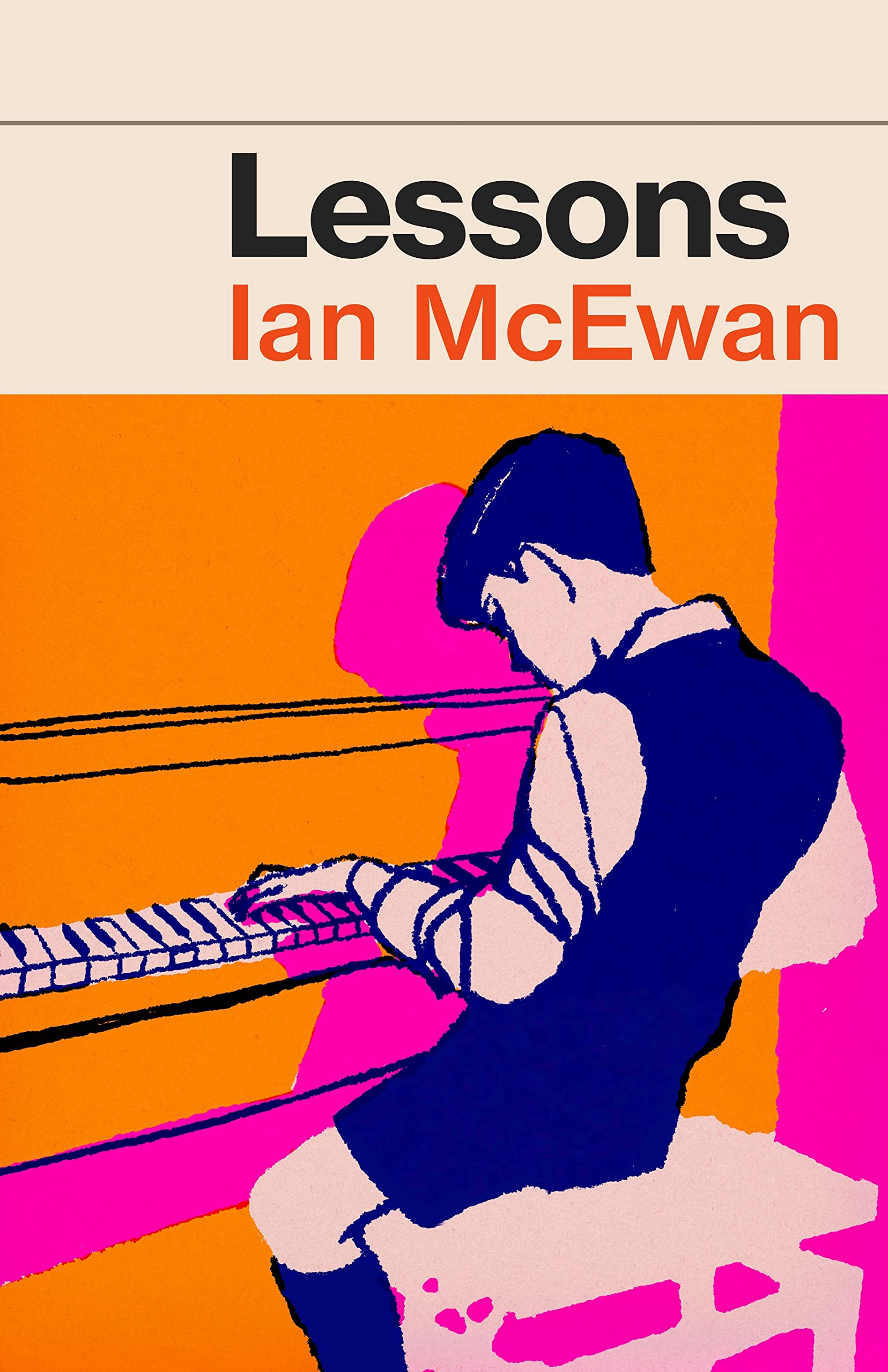

The aspect of the novel that I found the most thought-provoking is that the act that precipitates Stephen’s subsequent descent into alcoholism and despair is (relatively speaking) quite a small-scale one. There’s a lot of build-up to it, a lot of manipulative anticipation created. In the lead-up to the revelation, we hear about a range of horrifying atrocities—booby-traps and bombs; gangs kidnapping, torturing, and murdering people; cold-blooded shootings of people pulled from their cars in front of their families—so it’s almost an anti-climax when we find out that what Stephen did (“all” Stephen did) was shoot an unarmed teenager. It happens during a house search, a routine but also very tense operation: everything, we have learned by this point, is unpredictable in Belfast, and being on edge is a way of life for the soldiers on patrol. Stephen is posted in the alley; when the boy comes out of the back door, all Stephen registers is that “his hands were not quite empty.” Afterwards, Stephen is encouraged to dwell on the perceived threat: “if I’d believed my life was in danger then I’d had every right to do as I did.” He does as he’s told, and in the end there are no formal consequences beyond his being relocated out of Ireland.

The aspect of the novel that I found the most thought-provoking is that the act that precipitates Stephen’s subsequent descent into alcoholism and despair is (relatively speaking) quite a small-scale one. There’s a lot of build-up to it, a lot of manipulative anticipation created. In the lead-up to the revelation, we hear about a range of horrifying atrocities—booby-traps and bombs; gangs kidnapping, torturing, and murdering people; cold-blooded shootings of people pulled from their cars in front of their families—so it’s almost an anti-climax when we find out that what Stephen did (“all” Stephen did) was shoot an unarmed teenager. It happens during a house search, a routine but also very tense operation: everything, we have learned by this point, is unpredictable in Belfast, and being on edge is a way of life for the soldiers on patrol. Stephen is posted in the alley; when the boy comes out of the back door, all Stephen registers is that “his hands were not quite empty.” Afterwards, Stephen is encouraged to dwell on the perceived threat: “if I’d believed my life was in danger then I’d had every right to do as I did.” He does as he’s told, and in the end there are no formal consequences beyond his being relocated out of Ireland.

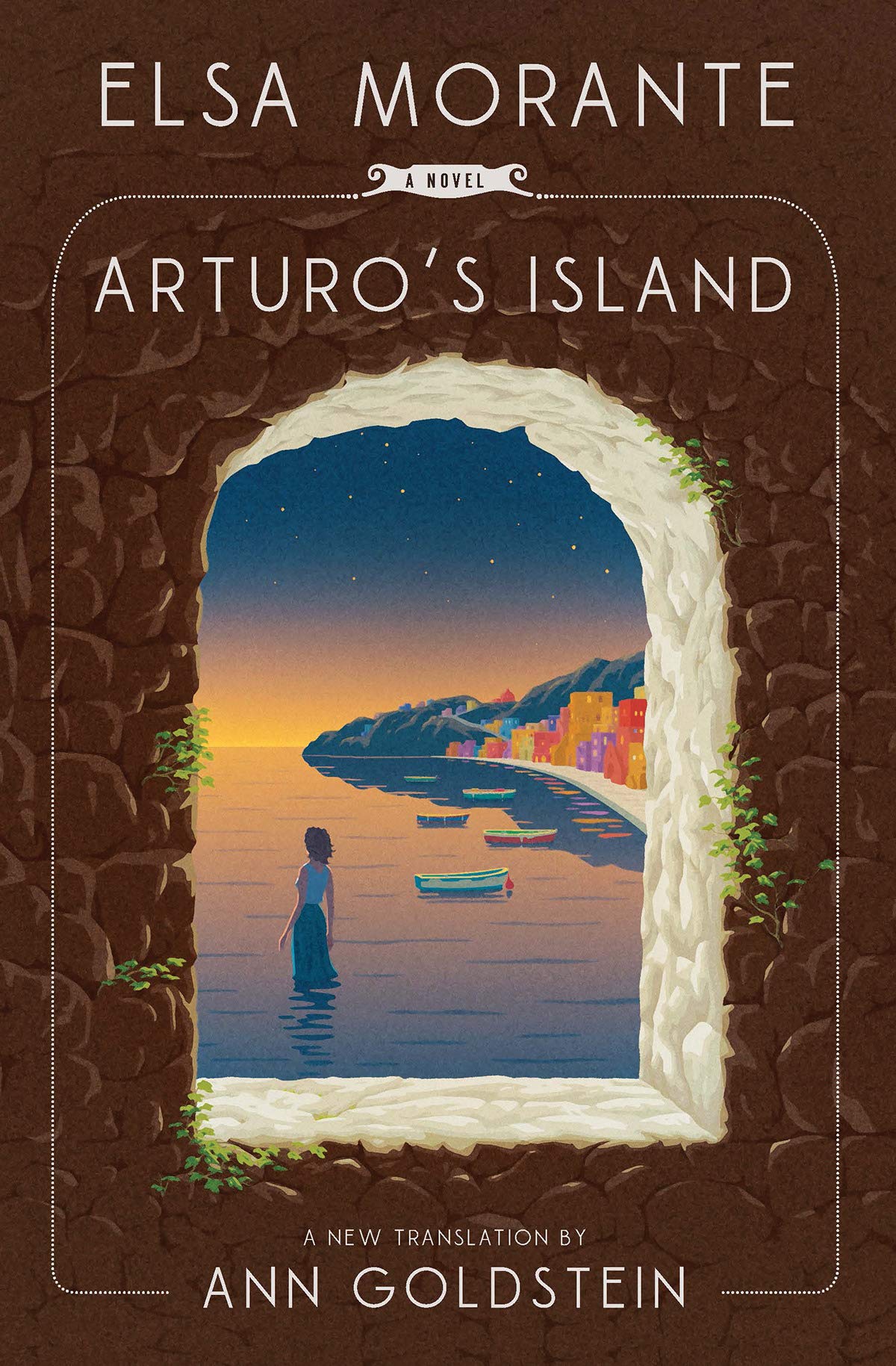

We thought that absence of solace or redemption had to be deliberate: that Morante had to be setting us up to see how wrong Arturo is, and to infer explanations and justifications (perhaps) for his wrongness, without ever letting us escape from it. Assuming the goal was immersion, emotion, and discomfort (with a significant tincture of pity, because Arturo really has a pretty deprived and distorted life) it’s a novel that is very good by the Lewes Standard (matching means to ends, a measure of greatness I derive from GHL’s assertion that Austen was “the greatest artist that has ever written, using the term to signify the most perfect mastery over the means to her end”). There are some other good things about the novel, too. The descriptions of the island are full of vivid details, and you really get a strong sense of Arturo’s strange life there, running wild and shaping his own strange identity from his father’s books. It’s also (and again, we thought maybe this was purposeful) a powerful antidote to sentimental or picturesque notions of Italy: it makes sense to me that the novel as Elena Ferrante’s endorsement, as her novels too (IMHO etc.) are ugly and unsentimental and driven by raw emotion–and, as Arturo’s Island is (at least implicitly), highly critica of certain strains of macho Italian masculinity. No flowery Tuscan hills here; no operatic gorgeousness; no above all, no love.

We thought that absence of solace or redemption had to be deliberate: that Morante had to be setting us up to see how wrong Arturo is, and to infer explanations and justifications (perhaps) for his wrongness, without ever letting us escape from it. Assuming the goal was immersion, emotion, and discomfort (with a significant tincture of pity, because Arturo really has a pretty deprived and distorted life) it’s a novel that is very good by the Lewes Standard (matching means to ends, a measure of greatness I derive from GHL’s assertion that Austen was “the greatest artist that has ever written, using the term to signify the most perfect mastery over the means to her end”). There are some other good things about the novel, too. The descriptions of the island are full of vivid details, and you really get a strong sense of Arturo’s strange life there, running wild and shaping his own strange identity from his father’s books. It’s also (and again, we thought maybe this was purposeful) a powerful antidote to sentimental or picturesque notions of Italy: it makes sense to me that the novel as Elena Ferrante’s endorsement, as her novels too (IMHO etc.) are ugly and unsentimental and driven by raw emotion–and, as Arturo’s Island is (at least implicitly), highly critica of certain strains of macho Italian masculinity. No flowery Tuscan hills here; no operatic gorgeousness; no above all, no love. Slowly she set off in the direction of the Rosenlund Canal. In order to make herself look a little shorter and older, she stooped over her walker. She had pulled on a white fabric sunhat with a wide brim, which hid her hair and part of her face. No one took any notice of the elderly lady. . . . The best thing was that none of the people bustling about took any notice of her. An elderly lady out and about in the lovely weather didn’t attract much attention.

Slowly she set off in the direction of the Rosenlund Canal. In order to make herself look a little shorter and older, she stooped over her walker. She had pulled on a white fabric sunhat with a wide brim, which hid her hair and part of her face. No one took any notice of the elderly lady. . . . The best thing was that none of the people bustling about took any notice of her. An elderly lady out and about in the lovely weather didn’t attract much attention. I suppose Maud’s ability to get away with her petty crime spree is a cautionary tale about the dangers of ageism and sexism, which contribute to obscuring the truth about people. But compared to the moral and psychological layers that emerge from Janina’s murders in

I suppose Maud’s ability to get away with her petty crime spree is a cautionary tale about the dangers of ageism and sexism, which contribute to obscuring the truth about people. But compared to the moral and psychological layers that emerge from Janina’s murders in

Is it true that Eunice Parchman–and her accomplice, the same friend the unknowing Coverdales tried to keep away from their home–killed this hapless family “because she could not read or write”? Rendell’s striking opening is as much provocation as declaration, I think. It is certainly true that Eunice’s illiteracy haunts, shames, and distorts her life. It is easy to imagine a version of her story in which, as a result, we pity her and direct our antipathy at a society that repeatedly fails her–fails to educate her, fails to support her, fails to make it safe for her to overcome this debilitating disadvantage–while she retreats into the safety of suspicious solitude:

Is it true that Eunice Parchman–and her accomplice, the same friend the unknowing Coverdales tried to keep away from their home–killed this hapless family “because she could not read or write”? Rendell’s striking opening is as much provocation as declaration, I think. It is certainly true that Eunice’s illiteracy haunts, shames, and distorts her life. It is easy to imagine a version of her story in which, as a result, we pity her and direct our antipathy at a society that repeatedly fails her–fails to educate her, fails to support her, fails to make it safe for her to overcome this debilitating disadvantage–while she retreats into the safety of suspicious solitude: Rendell’s opening line is thus a bit of a feint, I think: it seems to set up a novel about the consequences of social and educational failures, but unlike, say, Dickens’s account of Magwitch’s history in Great Expectations, she doesn’t really account for Eunice’s criminality on those terms alone, leaving us to point the finger at ourselves for creating an uncaring system that generates criminals where there should have been (and still could be) a caring human being. Eunice seems irredeemable; Rendell doesn’t make a convincing case that she would have been a different person–and the Coverdales would have lived–if only she could read the printed word. It’s hard to be sure, though, and maybe that’s the question Rendell means to leave with her readers.

Rendell’s opening line is thus a bit of a feint, I think: it seems to set up a novel about the consequences of social and educational failures, but unlike, say, Dickens’s account of Magwitch’s history in Great Expectations, she doesn’t really account for Eunice’s criminality on those terms alone, leaving us to point the finger at ourselves for creating an uncaring system that generates criminals where there should have been (and still could be) a caring human being. Eunice seems irredeemable; Rendell doesn’t make a convincing case that she would have been a different person–and the Coverdales would have lived–if only she could read the printed word. It’s hard to be sure, though, and maybe that’s the question Rendell means to leave with her readers.

I didn’t start enjoying the novel more just because the plot became more engrossing, though it did–or because the prose became more pleasurable, because it really didn’t. The other thing that happened was I got used to the slow pace and came to appreciate all the cultural context I was getting through what initially seemed like digressions. It’s true that all the many (many!) descriptions of meals aren’t strictly necessary to the plot, but they certainly added to my sense of what life in Shanghai in the 1990s was like, as did the meticulous accounts of where and how people live:

I didn’t start enjoying the novel more just because the plot became more engrossing, though it did–or because the prose became more pleasurable, because it really didn’t. The other thing that happened was I got used to the slow pace and came to appreciate all the cultural context I was getting through what initially seemed like digressions. It’s true that all the many (many!) descriptions of meals aren’t strictly necessary to the plot, but they certainly added to my sense of what life in Shanghai in the 1990s was like, as did the meticulous accounts of where and how people live: I also really enjoyed the role of Chen’s poetry in his life and in his case–and in the case against him. The idea that his elusive (and allusive) verses harbor subversive messages at once works with the intense suspicion shown by loyal Party members towards anything suggestive of a “Western bourgeois decadent lifestyle” and seemed to me a sly play on the literary difficulty of modernist poetry and the challenge of figuring out what it means. Poring over Chen’s poem “Night Talk,” Zhang wonders if the phrase “mind’s square” is a reference to Tiananmen Square:

I also really enjoyed the role of Chen’s poetry in his life and in his case–and in the case against him. The idea that his elusive (and allusive) verses harbor subversive messages at once works with the intense suspicion shown by loyal Party members towards anything suggestive of a “Western bourgeois decadent lifestyle” and seemed to me a sly play on the literary difficulty of modernist poetry and the challenge of figuring out what it means. Poring over Chen’s poem “Night Talk,” Zhang wonders if the phrase “mind’s square” is a reference to Tiananmen Square: It certainly is easy to fall out of the habit of blogging–and this in spite of the fact that the most fun I’ve had in the last little while was writing my two previous posts. I enjoyed doing them so much! I felt more engaged and productive than I had in a long time, not because I was fulfilling any external obligation but because I was sorting out my ideas and putting them into words. To be honest, though, in both cases I was also a bit disappointed that the posts didn’t spark more discussion in the comments, and that set me back a bit, as it made me wonder what exactly I thought I was doing here–not a new question, and one every blogger comes back to at intervals, I’m sure. I appreciate the comments I did get, of course, and there was some Twitter discussion around the Odyssey post, which as I know has been remarked before is a common pattern now–though I can’t help but notice that there are other blogs that routinely do still get a steady flow of comments. Anyway, for a while I felt somewhat deflated about blogging and that sapped my motivation for posting. I know, I know: it’s about the intrinsic value of the writing itself, which my experience of actually writing the Woolf and Homer posts more than proved–except it isn’t quite, because if that was all, we’d write offline, right?

It certainly is easy to fall out of the habit of blogging–and this in spite of the fact that the most fun I’ve had in the last little while was writing my two previous posts. I enjoyed doing them so much! I felt more engaged and productive than I had in a long time, not because I was fulfilling any external obligation but because I was sorting out my ideas and putting them into words. To be honest, though, in both cases I was also a bit disappointed that the posts didn’t spark more discussion in the comments, and that set me back a bit, as it made me wonder what exactly I thought I was doing here–not a new question, and one every blogger comes back to at intervals, I’m sure. I appreciate the comments I did get, of course, and there was some Twitter discussion around the Odyssey post, which as I know has been remarked before is a common pattern now–though I can’t help but notice that there are other blogs that routinely do still get a steady flow of comments. Anyway, for a while I felt somewhat deflated about blogging and that sapped my motivation for posting. I know, I know: it’s about the intrinsic value of the writing itself, which my experience of actually writing the Woolf and Homer posts more than proved–except it isn’t quite, because if that was all, we’d write offline, right? It hasn’t helped my blogging motivation that not much has been going on that seems very interesting. I certainly haven’t read anything since the Odyssey that was particularly memorable. I’ve puttered through some romance novels that proved entertaining enough but aren’t likely candidates for my “Frequent Rereads” club. Two were by Helena Hunting, a new-to-me author–Meet Cute and Lucky Charm, both of which were pretty good; one was Olivia Dade’s Teach Me, which had good ingredients but seemed just too careful to me, too self-consciously aware of hitting all the ‘right’ notes; and finally Christina Lauren’s Roomies, which was diverting enough until the heroine breaks out of her career funk by writing her first (ever!) feature essay, submitting it (not pitching it, submitting it) to the New Yorker, and learning in THREE WEEKS that it has been accepted. I’m not sure which struck me as more clearly a fantasy: the acceptance itself or the timeline.

It hasn’t helped my blogging motivation that not much has been going on that seems very interesting. I certainly haven’t read anything since the Odyssey that was particularly memorable. I’ve puttered through some romance novels that proved entertaining enough but aren’t likely candidates for my “Frequent Rereads” club. Two were by Helena Hunting, a new-to-me author–Meet Cute and Lucky Charm, both of which were pretty good; one was Olivia Dade’s Teach Me, which had good ingredients but seemed just too careful to me, too self-consciously aware of hitting all the ‘right’ notes; and finally Christina Lauren’s Roomies, which was diverting enough until the heroine breaks out of her career funk by writing her first (ever!) feature essay, submitting it (not pitching it, submitting it) to the New Yorker, and learning in THREE WEEKS that it has been accepted. I’m not sure which struck me as more clearly a fantasy: the acceptance itself or the timeline. The other book I finished recently is Wayson Choy’s The Jade Peony, for my book club. I wanted to like this one more than I did. It certainly illuminates a lot about the Chinese community in Vancouver in the time it is set (the 1930s and 1940s): one thing our discussion made me appreciate more than I did at first is how deftly telling the story from the children’s perspectives lets Choy handle the historical and political contexts, as they often don’t quite understand what is happening and so our main focus is on the young characters’ emotional experiences in the midst of them. The book reads more like linked short stories than a novel, and for me it lacked both momentum and continuity as a result (that’s not my favorite genre), but many of the specific scenes have a lot of intensity and I think they will linger with me more than I initially thought.

The other book I finished recently is Wayson Choy’s The Jade Peony, for my book club. I wanted to like this one more than I did. It certainly illuminates a lot about the Chinese community in Vancouver in the time it is set (the 1930s and 1940s): one thing our discussion made me appreciate more than I did at first is how deftly telling the story from the children’s perspectives lets Choy handle the historical and political contexts, as they often don’t quite understand what is happening and so our main focus is on the young characters’ emotional experiences in the midst of them. The book reads more like linked short stories than a novel, and for me it lacked both momentum and continuity as a result (that’s not my favorite genre), but many of the specific scenes have a lot of intensity and I think they will linger with me more than I initially thought. We chose Joy Kogawa’s Obasan for our next read. I’ve been trying to sort out why I’m not entirely happy about this. It makes perfect sense given our policy of following threads from one book to the next, and also Obasan is widely considered a CanLit classic, so it’s not that I don’t expect it to be a good book. I was mildly frustrated, though, that one of the arguments made in its favor was that The Jade Peony was very educational (about a time and place and culture not well-known to the group members) and Obasan would be more of the same. It will be, I’m sure, and in some ways this is an excellent reason for us to read and discuss it. But at the same time this “literature as beneficent medicine for well-intentioned consumers” approach is what turns me off

We chose Joy Kogawa’s Obasan for our next read. I’ve been trying to sort out why I’m not entirely happy about this. It makes perfect sense given our policy of following threads from one book to the next, and also Obasan is widely considered a CanLit classic, so it’s not that I don’t expect it to be a good book. I was mildly frustrated, though, that one of the arguments made in its favor was that The Jade Peony was very educational (about a time and place and culture not well-known to the group members) and Obasan would be more of the same. It will be, I’m sure, and in some ways this is an excellent reason for us to read and discuss it. But at the same time this “literature as beneficent medicine for well-intentioned consumers” approach is what turns me off  My recent viewing has actually been more engrossing than my recent reading: we just finished watching Rectify, which I thought was superb–it is intense, thoughtful, and full of turns that surprise without seeming like cheap twists. It is very much character- rather than plot-driven, and it works because every performance is entirely believable. I hadn’t even heard of Rectify before I noticed it on a list of ‘best TV dramas’ and decided we should give it a try. It is not at all what I expected from the premise (a man is released after 19 years on death row): it is much more about how he and his family and community deal with this unthinkable change in circumstances then about the case and his guilt or innocence–though what they do with that question is also very interesting.

My recent viewing has actually been more engrossing than my recent reading: we just finished watching Rectify, which I thought was superb–it is intense, thoughtful, and full of turns that surprise without seeming like cheap twists. It is very much character- rather than plot-driven, and it works because every performance is entirely believable. I hadn’t even heard of Rectify before I noticed it on a list of ‘best TV dramas’ and decided we should give it a try. It is not at all what I expected from the premise (a man is released after 19 years on death row): it is much more about how he and his family and community deal with this unthinkable change in circumstances then about the case and his guilt or innocence–though what they do with that question is also very interesting.