And now, in this low and critical moment, something in Penelope, something which had understood courage and resource and action, though she herself had never been brave or resourceful or active, stirred and shook itself. The pirate woman, Jane Moore, the Aztec girl, Xhalama, the misunderstood Tudor stateswoman and others of their blood, stood by her bed, urging her to save herself . . . and to justify them.

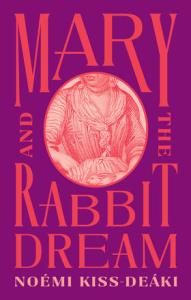

In his excellent ‘Afterword’ to the British Library Women Writers edition of Lady Living Alone, Simon Thomas (known to many of us from his excellent blog Stuck in a Book) highlights the genre trickery that makes this little novel so slyly surprising. Initially it conforms to the tropes, tone, and expectations of “comic, domestic fiction.” It centers on Penelope Shadow, an awkward, unobtrusive, and largely ineffectual woman with an overpowering fear of being alone in the house. One day Penelope buys a typewriter, shuts herself in her room, and rattles away at it day and night until she produces what becomes the first in series of historical novels. “Miss Shadow,” we’re told, “had at last found the job for which she was suited, a job which did not demand regular hours, spurious politeness nor the soul-jarring contact with people; so, through good years and bad, she persevered with it” until one of her books, Mexican Flower, is a big success and makes her enough money to move out of her half-sister’s house into one of her very own.

Hooray! you might well think: she has written her way to independence. But this is where her difficulty with being alone becomes not just a quirky character trait but an obstacle to her contentment. Driving home one night in a snowstorm, Penelope realizes that because the latest in her series of housekeepers is gone, she would have to be alone, so instead she pulls up at the Plantation Guest House. There, during the course of a generally uncomfortable stay, she meets “the boy,” a handsome young man named Terry Munce, who looks after her so readily and ably that she ends up offering him the job as housekeeper.

Terry is a great addition to Penelope’s household and her life: he takes excellent care of her, even giving her massages when she is stiff and tired from typing. Once again things seem to be going well for Penelope, but Terry’s presence kindles gossip. When he confronts her about it, he shocks her by adding “I happen to be terribly in love with you.” He kisses her, “and Penelope was lost.” She agrees that they should marry. Hooray! you might think: our mousy heroine has found love. But before the chapter closes, the novel shifts gears, giving us a glimpse of the real Terry in his “expression of calculating triumph”: “After all, one likes six months of hard labour to bear some result.”

Terry is a great addition to Penelope’s household and her life: he takes excellent care of her, even giving her massages when she is stiff and tired from typing. Once again things seem to be going well for Penelope, but Terry’s presence kindles gossip. When he confronts her about it, he shocks her by adding “I happen to be terribly in love with you.” He kisses her, “and Penelope was lost.” She agrees that they should marry. Hooray! you might think: our mousy heroine has found love. But before the chapter closes, the novel shifts gears, giving us a glimpse of the real Terry in his “expression of calculating triumph”: “After all, one likes six months of hard labour to bear some result.”

Lady Living Alone does not shift immediately from domestic comedy to domestic suspense: the next phase of the novel traces the rifts that emerge in Terry and Penelope’s relationship. He behaves badly, but he is not overtly sinister, and for some time Penelope’s position seems more pathetic than perilous. But then things take a turn, and Penelope has to wonder if it is possible that this young man she has befriended, trusted, and loved might in fact be trying to do away with her . . .

I don’t want to spoil the fun of your finding out for yourself how things turn out. Something I found particularly interesting about the novel’s conclusion that doesn’t bear directly on plot revelations is its connection to Penelope’s writing. It is generally seen as eccentricity by those around her—”If she think you can keep a husband by hitting a typewriter all day and all night,” she overhears one of her servants muttering at one point, “let her find out different for herself”—and no particular merits are ever ascribed to her novels. Her subjects are strong women, though, including Queen Elizabeth. “I know why she never married,” she scribbles in her notebook when she turns back to writing after her marriage:

Oh, she was as certain as though she had been there, that Elizabeth Tudor had never taken Leicester or Essex to her bed. Because if she had done she too, being human, would then have owned a master.

How does that happen, she wonders; “the balance swung so gently that it was not until one scale bumped heavily that you realised that there had been a disturbance.” She too is mastered in her marriage, not so much (at first) through overbearing conduct on Terry’s part but through her own love of him and her desire to be loved herself, to believe in what she thinks they have. When she finally realizes that he is a threat, that she is going to have to defend herself or die, her situation seems hopeless:

A poor little ageing creature, sick, doubting her own sanity, and broken in spirit. A pitiable little object to any observer, had there been one who could see and understand.

But there is more to Penelope Shadow than that: she has “made and known and understood some remarkable, courageous, fiery, indomitable women,” and from them she takes courage —and gets ideas. “If we are part of all we have been,” comments the narrator, “how much more are we part of all we have made?” I loved this moment, which picks up on an idea that has been central to a lot of my own work on women’s writing. “Lives do not serve as models,” Carolyn Heilbrun wrote in Writing A Woman’s Life; “only stories do that.” For Penelope, the stories she has written quite literally empower her—and then it is “over and done with, and Penelope was no more a clever, cunning, ruthless creature, but a gentle little woman with a conscience.”

—and gets ideas. “If we are part of all we have been,” comments the narrator, “how much more are we part of all we have made?” I loved this moment, which picks up on an idea that has been central to a lot of my own work on women’s writing. “Lives do not serve as models,” Carolyn Heilbrun wrote in Writing A Woman’s Life; “only stories do that.” For Penelope, the stories she has written quite literally empower her—and then it is “over and done with, and Penelope was no more a clever, cunning, ruthless creature, but a gentle little woman with a conscience.”

I read some of Norah Lofts’s own historical novels long ago: the one I particularly remember is The Concubine, about Anne Boleyn, though I am sure there were more in our nearby public library, where I used to sign out stacks of Tudor (and Ricardian) fiction every week. It is hard not to read some justification of her own work and heroines in the strength Penelope Shadow gets from hers. Lofts published Lady Living Alone under a pseudonym, Peter Curtis; perhaps she thought the message, that women’s ‘romantic fiction’ was more subversive than it seemed, would be more memorable coming from a ‘man.’

It has been a long time since I worked through Elizabeth Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë with a class. In fact, the last time I did so was the first year I began this blog series, in the

It has been a long time since I worked through Elizabeth Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë with a class. In fact, the last time I did so was the first year I began this blog series, in the

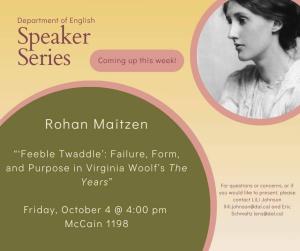

We started with Sherlock Holmes in Mystery & Detective Fiction this week. I’m not the world’s biggest Holmes enthusiast, but as I have documented here often enough over the years, I greatly appreciate The Hound of the Baskervilles, which we will get to on Wednesday. Today was “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” with its famous “interpret everything about a man from his hat” set piece, and “A Scandal in Bohemia,” with Irene Adler (“To Sherlock Holmes, she was always the woman”). These are good ones: I enjoy them. I think the class is going fine so far: it ought to be, considering how often I’ve taught it now! One thing I’m noticing is spotty attendance. It isn’t making me rethink my long-ago decision not to give grades for attendance, but it gives me food for thought in other ways, as this seems to be a trend in this class in recent years. Perhaps it’s because the course is an elective for pretty much everyone taking it, so they give it lower priority than their other obligations? Is it that students who don’t take a lot of English classes assume the pertinent course content is exclusively in the “textbooks” (what we call the “readings”!) and don’t expect our class time to offer much “value added”? I know that in some subjects lectures often do simply reiterate content in that way, but of course I’m not standing there rehearsing the plot of The Moonstone. Anyway, I try not to take it personally but it rather baffles me: what is the point in signing up to “take” a class but then not really “taking” it? Sure, you can read on your own (or, sigh, just search online summaries and call that “keeping up”), but unless all you are after is the course credit, aren’t you skipping the good part, not to mention the part you are actually paying for?

We started with Sherlock Holmes in Mystery & Detective Fiction this week. I’m not the world’s biggest Holmes enthusiast, but as I have documented here often enough over the years, I greatly appreciate The Hound of the Baskervilles, which we will get to on Wednesday. Today was “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” with its famous “interpret everything about a man from his hat” set piece, and “A Scandal in Bohemia,” with Irene Adler (“To Sherlock Holmes, she was always the woman”). These are good ones: I enjoy them. I think the class is going fine so far: it ought to be, considering how often I’ve taught it now! One thing I’m noticing is spotty attendance. It isn’t making me rethink my long-ago decision not to give grades for attendance, but it gives me food for thought in other ways, as this seems to be a trend in this class in recent years. Perhaps it’s because the course is an elective for pretty much everyone taking it, so they give it lower priority than their other obligations? Is it that students who don’t take a lot of English classes assume the pertinent course content is exclusively in the “textbooks” (what we call the “readings”!) and don’t expect our class time to offer much “value added”? I know that in some subjects lectures often do simply reiterate content in that way, but of course I’m not standing there rehearsing the plot of The Moonstone. Anyway, I try not to take it personally but it rather baffles me: what is the point in signing up to “take” a class but then not really “taking” it? Sure, you can read on your own (or, sigh, just search online summaries and call that “keeping up”), but unless all you are after is the course credit, aren’t you skipping the good part, not to mention the part you are actually paying for?

I pretended everything would be okay because it seemed impossible to always be saying goodbye. To blueberries. To the ocean. To ravens. To pelicans and plovers. To the cormorants. To the sunlight on the living room wall at four o’clock. To the sound of you in the next room.

I pretended everything would be okay because it seemed impossible to always be saying goodbye. To blueberries. To the ocean. To ravens. To pelicans and plovers. To the cormorants. To the sunlight on the living room wall at four o’clock. To the sound of you in the next room. In my Victorian Women Writers seminar, we are discussing Margaret Oliphant’s Autobiography. When I was drawing up the syllabus for this version of the course, I included this book without much reflection, as it has always been a staple of the reading list. Preparing for class over the past few days has been a bit rough, though, as the last time I had actually read it was

In my Victorian Women Writers seminar, we are discussing Margaret Oliphant’s Autobiography. When I was drawing up the syllabus for this version of the course, I included this book without much reflection, as it has always been a staple of the reading list. Preparing for class over the past few days has been a bit rough, though, as the last time I had actually read it was

In Mystery & Detective Fiction, we have begun our work on The Moonstone. I usually really enjoy teaching this novel as I know it well enough now and am confident enough in my own ideas about it that, while I do always reread it and update my notes, I can lead a fairly fluid discussion without worrying that we won’t get where I want us to go. Tomorrow is mostly “talk about Betteredge” day: I’ll start by just gathering up observations about what kind of fellow he is, considering both the things he explicitly says and how he says them—which is at least as important, given the novel’s emphasis on first-person testimony and the way eye-witnesses see according to their assumptions and prejudices. We can build out from there into a sense of the novel’s setting: what kind of world does Betteredge serve, what are the threats to or problems with that world, who in the novel begins to counter his point of view, and so on, which should lead us into Sergeant Cuff and what he brings to the investigation—and then the sources of his failures to solve the crime.

In Mystery & Detective Fiction, we have begun our work on The Moonstone. I usually really enjoy teaching this novel as I know it well enough now and am confident enough in my own ideas about it that, while I do always reread it and update my notes, I can lead a fairly fluid discussion without worrying that we won’t get where I want us to go. Tomorrow is mostly “talk about Betteredge” day: I’ll start by just gathering up observations about what kind of fellow he is, considering both the things he explicitly says and how he says them—which is at least as important, given the novel’s emphasis on first-person testimony and the way eye-witnesses see according to their assumptions and prejudices. We can build out from there into a sense of the novel’s setting: what kind of world does Betteredge serve, what are the threats to or problems with that world, who in the novel begins to counter his point of view, and so on, which should lead us into Sergeant Cuff and what he brings to the investigation—and then the sources of his failures to solve the crime. I don’t want you to blame yourself for what happened. I know you would have come to get me if you could, but I couldn’t have gone anyway, not with Agnes ill.

I don’t want you to blame yourself for what happened. I know you would have come to get me if you could, but I couldn’t have gone anyway, not with Agnes ill.

This is very much Kivrin’s experience, and thus ours, as we read both Willis’s conventional narration of Kivrin’s time in 1348 and the more fragmentary bulletins Kivrin records for those back home in her own time, which gradually take on more and more the character of the few remaining testaments of those who actually lived through the plague years, documents which had once seemed to Kivrin melodramatic and implausible. Where the archive is scant, as it must be in such dire circumstances, we rely on our imaginations to fill in the blanks and to fully humanize it. I don’t think anyone could read Doomsday Book and not be overcome with horror and pity for those who faced what they understandably believed was the end of the world.

This is very much Kivrin’s experience, and thus ours, as we read both Willis’s conventional narration of Kivrin’s time in 1348 and the more fragmentary bulletins Kivrin records for those back home in her own time, which gradually take on more and more the character of the few remaining testaments of those who actually lived through the plague years, documents which had once seemed to Kivrin melodramatic and implausible. Where the archive is scant, as it must be in such dire circumstances, we rely on our imaginations to fill in the blanks and to fully humanize it. I don’t think anyone could read Doomsday Book and not be overcome with horror and pity for those who faced what they understandably believed was the end of the world. —until his turn comes as well. It turns out that Father Roche sees Kivrin’s arrival as literally miraculous, her presence among them a kind of gift or grace from God, whose love and mercy he never doubts, in spite of everything he sees and experiences. For Kivrin, fighting against a malicious, invisible enemy, and always thinking of those who care for her and especially of her tutor, Mr. Dunworthy, whom she believes to the very end will come to her rescue, the line between science and religion starts to blur. Who is Mr. Dunworthy to Kivrin, after all, but an unseen presence—the thought of whom gives her hope and strength in her darkest hours—and an audience for her testimony, which is spoken into a recording device which it had seemed so clever to place in her wrist, so that she would appear to be praying? “It’s strange,” she says in one of her final such messages to someone who may or may not ever receive it;

—until his turn comes as well. It turns out that Father Roche sees Kivrin’s arrival as literally miraculous, her presence among them a kind of gift or grace from God, whose love and mercy he never doubts, in spite of everything he sees and experiences. For Kivrin, fighting against a malicious, invisible enemy, and always thinking of those who care for her and especially of her tutor, Mr. Dunworthy, whom she believes to the very end will come to her rescue, the line between science and religion starts to blur. Who is Mr. Dunworthy to Kivrin, after all, but an unseen presence—the thought of whom gives her hope and strength in her darkest hours—and an audience for her testimony, which is spoken into a recording device which it had seemed so clever to place in her wrist, so that she would appear to be praying? “It’s strange,” she says in one of her final such messages to someone who may or may not ever receive it; In summer, and particularly when the wind blows from the south-west across the lawn, the septic tank gives out a strong stench, and guests move uneasily nearer the house. ‘Oh, it is a body,’ the girls say. ‘We have a body in there, no one you know. It decomposes, of course, but so slowly one quite despairs.’

In summer, and particularly when the wind blows from the south-west across the lawn, the septic tank gives out a strong stench, and guests move uneasily nearer the house. ‘Oh, it is a body,’ the girls say. ‘We have a body in there, no one you know. It decomposes, of course, but so slowly one quite despairs.’ How much of a shadow did AI cast over my term? It’s actually a bit hard to say. I tried not to be preoccupied with it. I had just two cases of clear use, both evident from their hallucinations. There were many other submissions that made me wonder. I hated that. I don’t want to be suspicious about my students; I certainly don’t want fluency to become grounds for accusations. I’ve seen a lot of professors confidently declaring that they can spot AI usage. Maybe I’m naïve, or maybe I don’t assign tricky enough questions, or maybe my general expectations are too low, but I’m not nearly so confident. I know what they mean when they talk about the vacuity of AI responses and the other (likely) “tells”—previously rare (for students) words like “delve,” everything coming in threes, too-rapid turns to universalizing proclamations. I caught what I considered a whiff of AI from a lot of students’ assignments. But many of these things used to show up before there was Chat GPT, sometimes because of high school teachers who taught them that’s what good writing or literary analysis should look like, or because some students are authentically fluent, even glib, and nobody has pulled them up short before and demanded they say things that have substance, not just style. I honestly don’t really know how to proceed, pedagogically, beyond continuing to make the best case I can for the reasons to do your own reading, writing and thinking. I do know that I wish we could slow the infiltration of AI into all of the tools we and our students routinely use. I also believe that there are many students still conscientiously doing their own work, and they deserve to have teachers who trust them. I try hard to be that teacher unless evidence to the contrary really stares me in the face.

How much of a shadow did AI cast over my term? It’s actually a bit hard to say. I tried not to be preoccupied with it. I had just two cases of clear use, both evident from their hallucinations. There were many other submissions that made me wonder. I hated that. I don’t want to be suspicious about my students; I certainly don’t want fluency to become grounds for accusations. I’ve seen a lot of professors confidently declaring that they can spot AI usage. Maybe I’m naïve, or maybe I don’t assign tricky enough questions, or maybe my general expectations are too low, but I’m not nearly so confident. I know what they mean when they talk about the vacuity of AI responses and the other (likely) “tells”—previously rare (for students) words like “delve,” everything coming in threes, too-rapid turns to universalizing proclamations. I caught what I considered a whiff of AI from a lot of students’ assignments. But many of these things used to show up before there was Chat GPT, sometimes because of high school teachers who taught them that’s what good writing or literary analysis should look like, or because some students are authentically fluent, even glib, and nobody has pulled them up short before and demanded they say things that have substance, not just style. I honestly don’t really know how to proceed, pedagogically, beyond continuing to make the best case I can for the reasons to do your own reading, writing and thinking. I do know that I wish we could slow the infiltration of AI into all of the tools we and our students routinely use. I also believe that there are many students still conscientiously doing their own work, and they deserve to have teachers who trust them. I try hard to be that teacher unless evidence to the contrary really stares me in the face. Anyway. The first-year course went fine, I thought. I wish it didn’t have to be a lecture class, but with 90 students (next year we will all have 120), there’s really no other option. I always try to get some class discussion going, and we meet in tutorial groups of “only” 30 once a week as well, but the real answer to “what to do about AI” is the same as the answer to most pedagogical problems we have: smaller classes, closer relationships, more individual attention, especially to their writing. I probably won’t be teaching a first-year class next year, for the first time in a long time, because I will have a course release for serving as our undergraduate program coordinator. In part but not just because of AI, I am glad for the chance to give the course a refresh, maybe even a complete redesign. I want to keep using specifications grading but I’d like to reconsider the components and bundles I devised. I want to think about the readings again, too, maybe moving towards more deliberate thematic groupings, or including some full-length novels again. When you teach a course for several years in a row the easiest thing to do is repeat what you just did, because the deadlines for course proposals and timetabling and book orders come earlier and earlier. I’ve done a lot of different first-year classes since I started at Dalhousie in 1995. Who knows: the next version I develop might be my last! And maybe by the time I am offering it, probably in Fall 2026, the AI bubble will have burst. I mean, surely at some point the fact that it is no good—that it spews bullshit and destroys the environment and relies on theft—will matter, right? RIGHT?

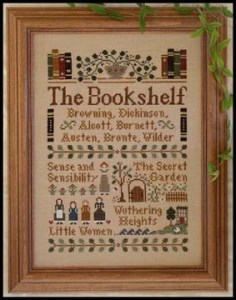

Anyway. The first-year course went fine, I thought. I wish it didn’t have to be a lecture class, but with 90 students (next year we will all have 120), there’s really no other option. I always try to get some class discussion going, and we meet in tutorial groups of “only” 30 once a week as well, but the real answer to “what to do about AI” is the same as the answer to most pedagogical problems we have: smaller classes, closer relationships, more individual attention, especially to their writing. I probably won’t be teaching a first-year class next year, for the first time in a long time, because I will have a course release for serving as our undergraduate program coordinator. In part but not just because of AI, I am glad for the chance to give the course a refresh, maybe even a complete redesign. I want to keep using specifications grading but I’d like to reconsider the components and bundles I devised. I want to think about the readings again, too, maybe moving towards more deliberate thematic groupings, or including some full-length novels again. When you teach a course for several years in a row the easiest thing to do is repeat what you just did, because the deadlines for course proposals and timetabling and book orders come earlier and earlier. I’ve done a lot of different first-year classes since I started at Dalhousie in 1995. Who knows: the next version I develop might be my last! And maybe by the time I am offering it, probably in Fall 2026, the AI bubble will have burst. I mean, surely at some point the fact that it is no good—that it spews bullshit and destroys the environment and relies on theft—will matter, right? RIGHT? My other class was The 19th-Century British Novel from Dickens to Hardy. I enjoyed it so much! The reading list was one I haven’t done since 2017: Bleak House, Adam Bede, Lady Audley’s Secret, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. It was particularly lovely to hear so many students say they had no fears about Bleak House because they had enjoyed David Copperfield so much last year in the Austen to Dickens course. I think I have mentioned before in these posts that in recent years I have been making a conscious effort to wean myself from my teaching notes. I still prepare and bring quite a lot of notes, but I try to let that preparation sit in the background and set up topics and examples for discussion that then proceeds in a looser way. The notes are always there if I think we are losing focus or running out of steam, but I don’t worry about whether I’m following the plan I came with. It was interesting, then, to dip into my notes from that 2017 version, because I realized how much my approach has in fact changed since then. I was very glad to have them to draw on and adapt, but although if you’d asked me in 2017 whether I did much “formal” lecturing I would have said I did not, in fact they show that I did run much more scripted classes than I do now. The things I want to talk about have not changed that much, although of course I do browse recent criticism and introduce new angles or approaches that interest me. Basically, though, I guess my attitude to this class (and the Austen to Dickens one) is “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”: I believe them to be rigorous, stimulating, and fun, and students seem to agree. Unlike the first-year course, then, these ones are likely to stay more or less the same until I retire. More or less, not exactly! They have evolved a lot already, in more ways than my own teaching style, and I will not let them go stale. I wouldn’t want that for my own sake, never mind for my students’.

My other class was The 19th-Century British Novel from Dickens to Hardy. I enjoyed it so much! The reading list was one I haven’t done since 2017: Bleak House, Adam Bede, Lady Audley’s Secret, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. It was particularly lovely to hear so many students say they had no fears about Bleak House because they had enjoyed David Copperfield so much last year in the Austen to Dickens course. I think I have mentioned before in these posts that in recent years I have been making a conscious effort to wean myself from my teaching notes. I still prepare and bring quite a lot of notes, but I try to let that preparation sit in the background and set up topics and examples for discussion that then proceeds in a looser way. The notes are always there if I think we are losing focus or running out of steam, but I don’t worry about whether I’m following the plan I came with. It was interesting, then, to dip into my notes from that 2017 version, because I realized how much my approach has in fact changed since then. I was very glad to have them to draw on and adapt, but although if you’d asked me in 2017 whether I did much “formal” lecturing I would have said I did not, in fact they show that I did run much more scripted classes than I do now. The things I want to talk about have not changed that much, although of course I do browse recent criticism and introduce new angles or approaches that interest me. Basically, though, I guess my attitude to this class (and the Austen to Dickens one) is “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”: I believe them to be rigorous, stimulating, and fun, and students seem to agree. Unlike the first-year course, then, these ones are likely to stay more or less the same until I retire. More or less, not exactly! They have evolved a lot already, in more ways than my own teaching style, and I will not let them go stale. I wouldn’t want that for my own sake, never mind for my students’. This is all very general, without the kind of “here’s what we talked about today” specificity that I used to incorporate when I really did post nearly every week about my classes. (There are 318 posts in that

This is all very general, without the kind of “here’s what we talked about today” specificity that I used to incorporate when I really did post nearly every week about my classes. (There are 318 posts in that  What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

What a nice conversation unfolded under my previous post! I suppose it isn’t surprising that those of us who gather online to share our love of books also share a lot of experiences with books, including making often difficult decisions about what to keep. Acquiring books is the easy part, as we all know, especially because our various social channels are constantly alerting us to tempting new ones. I have really appreciated everyone’s comments.

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (

I read two fabulous memoirs in 2024: Mark Bostridge’s In Pursuit of Love (which deserved but did not get its own post) and Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolf (

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be

If I had to identify a low point of my reading year, it would probably be  I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s

I’m a bit disappointed in how much (or, I should say, how little) writing I got done in 2024. It was my slowest year yet for reviews at the TLS, with just two, of Perry’s Enlightenment and, “in brief,” Sara Maitland’s True North. (I am working now on a review of Anne Tyler’s Three Days in June, so they haven’t quite forgotten me!) I reviewed three novels for Quill and Quire in 2024: Elaine McCluskey’s

In my

In my  So I started 2024 by clearing out a lot of books. The other change since the separation has been to my reading time. I don’t quite understand why, but there seem to be a lot more hours in the day now that I live alone! I have wasted an awful lot of them watching TV, and many of them idly scrolling online, and plenty also just moping or mourning. I think (though this may be just making excuses) that I should not be too hard on myself about these bad habits, as the past few years have been pretty tough and we are all entitled to our coping strategies. I make intermittent resolutions to do better, to use my time better; I have made some of these for 2025. (Yes, blogging regularly again is one of them. We’ll see.) However! I have had more time for reading, and I have sometimes taken advantage of it. I have especially enjoyed taking time to read in the mornings. For many years—around two decades, really—mornings were my least favorite time of the day, what with all the kid stuff (breakfasts, lunches, getting dressed, remembering backpacks and permission slips and other forms, trying to get out the door on time) on top of bracing for my own work days, with the non-trivial (for me) anxiety of driving in winter weather adding a nice additional layer of stress from November through April. Things were simpler once the kids were older then out of the house, but I never felt like it was a good time for relaxing: I still had to get off to work, for one thing. Now, between habitually waking up early and living easy walking distance to work, even on weekdays I can afford to get in some peaceful reading while I have my tea and toast. We used to end most days in front of the TV; I still do that, especially on days when I’ve read a lot for work, but other days I can settle into my reading chair, put on some quiet music, and there’s nothing and nobody to interrupt me.

So I started 2024 by clearing out a lot of books. The other change since the separation has been to my reading time. I don’t quite understand why, but there seem to be a lot more hours in the day now that I live alone! I have wasted an awful lot of them watching TV, and many of them idly scrolling online, and plenty also just moping or mourning. I think (though this may be just making excuses) that I should not be too hard on myself about these bad habits, as the past few years have been pretty tough and we are all entitled to our coping strategies. I make intermittent resolutions to do better, to use my time better; I have made some of these for 2025. (Yes, blogging regularly again is one of them. We’ll see.) However! I have had more time for reading, and I have sometimes taken advantage of it. I have especially enjoyed taking time to read in the mornings. For many years—around two decades, really—mornings were my least favorite time of the day, what with all the kid stuff (breakfasts, lunches, getting dressed, remembering backpacks and permission slips and other forms, trying to get out the door on time) on top of bracing for my own work days, with the non-trivial (for me) anxiety of driving in winter weather adding a nice additional layer of stress from November through April. Things were simpler once the kids were older then out of the house, but I never felt like it was a good time for relaxing: I still had to get off to work, for one thing. Now, between habitually waking up early and living easy walking distance to work, even on weekdays I can afford to get in some peaceful reading while I have my tea and toast. We used to end most days in front of the TV; I still do that, especially on days when I’ve read a lot for work, but other days I can settle into my reading chair, put on some quiet music, and there’s nothing and nobody to interrupt me.