Ruth sighs. It takes a great deal of energy, week after week, pressing her one remaining desire. “Try thinking of doneness as an awful illness then, and bound to be terminal. If you can’t even imagine feeling finished, you must think it’s a pretty terrible state to be in. So it’s about accepting what a person—me—regards as the end of the line. My definition of a fatal disease, which isn’t necessarily yours.”

Ruth sighs. It takes a great deal of energy, week after week, pressing her one remaining desire. “Try thinking of doneness as an awful illness then, and bound to be terminal. If you can’t even imagine feeling finished, you must think it’s a pretty terrible state to be in. So it’s about accepting what a person—me—regards as the end of the line. My definition of a fatal disease, which isn’t necessarily yours.”

A cautionary note about the rest of this post. Joan Barfoot’s Exit Lines is about someone planning to end their life. That is a tough topic for most people, I expect; it is certainly a tough one for me, and the novel brought up a lot of painful thoughts about Owen’s death in ways that I talk a bit about here. If you find discussions of suicide distressing, you should probably not read on. Canada now has a Suicide crisis helpline: call 9-8-8 if you need support. The same number also works in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Exit Lines is a brisk, smart, darkly comic novel about four people who move into a retirement community named—in typically euphemistic style for such places—the Idyll Inn. When the novel opens, our protagonists are creeping through the residence’s darkened corridors at 3 am. on a secret mission, the full details—and the outcome—of which we only gradually discover. In the meantime, Barfoot deftly recounts the story of their settling in and making what accommodations they can to their new circumstances—including the loss of autonomy and privacy, the depressingly bland dietary options, the relentless parade of activities that, though well-intentioned, inevitably come across as infantilizing, and the knowledge that the Idyll Inn will be the last place any of them call home.

The novel cuts back and forth between chapters taking us, bit by bit, further down those scary hallways (“Three busy hearts leap and bang. Legs are wobbly, hands a bit shaky, flesh feels fragile. These pajamas, nightgowns, slippers and robes are warm, but the skin beneath is unfairly goosebumpy, shivery”) and chapters that tell us more about Sylvia, Greta, George, and Ruth—including what their lives and families were like before they ended up at the Idyll Inn. They were not all strangers to each other before, but the bond they form at the Inn is a pleasantly bracing surprise. It is particularly important to Ruth, who has determined to control her eventual exit from the Idyll Inn by ending her own life, on her own timeline and in the way that she has figured out will be quickest, least painful, and easiest for those assisting her to cover up. In her new friends she finds (she hopes) allies and co-conspirators, though she waits until she is fairly sure of their loyalty before asking for what she admits is an “enormous” favour, “to be with me come the time. And . . . to help me.”

Ruth’s request understandably shocks the other three:

Friendship is supposed to be companionability, compatibility, trust, empathy, challenge, warmth, goodwill, consolation, and sustenance. Not this. What she’s asking has to be—or is not?—beyond all possible bounds.

What follows is a lot of arguing and and soul searching as each of the characters confronts questions from the pragmatic to the profound:

What do they believe? What are their values, and if any, their faiths? How do these apply to the small figure of Ruth sitting here?

What is compassion, how important is trust? . . .

What exactly is so exceptional about human beings? A single human being? Besides the fact that only human beings can even contemplate such a question.

The single most important question is “Who gets to decide?” Ruth says she does, but Ruth’s friends aren’t so sure, or at least (especially if they are going to help her) they need a better reason than because it’s what she wants (“What Ruth wants: ‘My time, my place, my way'”). “I’m sure I’d have an easier time,” Sylvia finally says, “if you had an awful illness that was going to be fatal.” Ruth’s reasons are not as straightforward as that, and perhaps they are not as good as that—but whose business is that but hers?

The others’ counterarguments are also not that robust. “God crops up,” but none of them is religious, or at least doctrinally secure, enough to insist that her plan is wrong or sinful. They are all in varying stages of physical decline, and the one certainty they share is that they will eventually leave the Idyll Inn the same way other residents have, their bodies whisked away as quickly and quietly as possible so as not to discourage the rest. Still, it’s one thing to die and another to kill yourself, or so they try to convince Ruth (“Those people who struggle to be alive. When we are safe and comfortable here—they feel their lives are precious even when they are so very difficult, but you do not feel your life is?” challenges Greta). Ruth is resolute, however, and finally, one by one, they come around. As Sylvia puts it after her own change of heart, “Whatever anyone says—lawyers, doctors, governments, religions, all those nincompoop moral busybodies that float around like weed seeds—we should be in charge of our own selves.”

The others’ counterarguments are also not that robust. “God crops up,” but none of them is religious, or at least doctrinally secure, enough to insist that her plan is wrong or sinful. They are all in varying stages of physical decline, and the one certainty they share is that they will eventually leave the Idyll Inn the same way other residents have, their bodies whisked away as quickly and quietly as possible so as not to discourage the rest. Still, it’s one thing to die and another to kill yourself, or so they try to convince Ruth (“Those people who struggle to be alive. When we are safe and comfortable here—they feel their lives are precious even when they are so very difficult, but you do not feel your life is?” challenges Greta). Ruth is resolute, however, and finally, one by one, they come around. As Sylvia puts it after her own change of heart, “Whatever anyone says—lawyers, doctors, governments, religions, all those nincompoop moral busybodies that float around like weed seeds—we should be in charge of our own selves.”

It sounds so simple, even inarguable, put like that, but the long journey our characters take to get there reminds us that it isn’t, as does the lived experience of anyone with direct experience of suicide. Details matter, of course. What Ruth is seeking is closest to what here in Canada we have termed “MAiD,” medical assistance in dying, although the help she asks for isn’t strictly speaking medical—but that is precisely because she does not have the kind of “awful illness” Sylvia initially thinks would be the only justification for death on her own terms. Sylvia is thinking of a physical illness, and that generally seems to be the easiest scenario for people to accept. The availability of MAiD to those with illnesses other people can’t so easily see for themselves, specifically mental illnesses, is more controversial. I’ve had several painfully searching conversations about this issue since Owen died: I am fortunate to have people in my life who are deeply thoughtful as well as remarkably kind, and I have been truly grateful to be able to talk with them about what having this option might have meant to Owen, as well as how I expect I would have felt about it as his mother. If I have reached any conclusions, they rest, as Sylvia’s does, on the primacy of autonomy as a right and a value. But there is nothing simple about any of it—the hypotheticals are as terrible for me to contemplate as the reality, if in different ways.

Barfoot simplifies things for her characters by emphasizing Ruth’s clarity of mind and purpose: whether you find her desire to die more or less acceptable as a result is going to depend on your values, but it does, I think, help answer the question “who decides” in her favour. Illnesses like depression affect, perhaps distort, people’s perception of reality: it is harder to defer to their autonomy, then, although perhaps it shouldn’t be, as what makes the most difference to someone’s quality of life is how they experience the world, how they experience life, not what other people insist it is actually like. Of course, we want to believe things will change for them, that they will get better, and most depressed people will. What does that mean about their right to say, as Ruth does, “my time, my place, my way,” or our right to intervene? One of the most insightful discussions I’ve heard about suicide since Owen’s death is an interview Hermione Lee did with Adam Phillips about his book On Giving Up. Phillips argues that we should be “able to acknowledge, not happily, that for some people, their lives are actually unbearable,” that the dogmatic insistence on life as the ultimate unassailable intrinsic good (what he calls “the ‘life is sacred’ line”) “means you are absolutely compelled to suffer whatever it is that’s inflicted on you,” which he rejects as an “intolerable position.” I agree, while recognizing as he does that this does not make any part of such a scenario anything other than heartbreaking, tragic. Phillips notes that the famous psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott never tried to dissuade anyone from suicide: “I just try to make sure they do it for the right reasons,” Winnicott said. I find that a defensible and principled position—but this is a case in which my head and my heart are in profound and perhaps intractable conflict.*

Barfoot simplifies things for her characters by emphasizing Ruth’s clarity of mind and purpose: whether you find her desire to die more or less acceptable as a result is going to depend on your values, but it does, I think, help answer the question “who decides” in her favour. Illnesses like depression affect, perhaps distort, people’s perception of reality: it is harder to defer to their autonomy, then, although perhaps it shouldn’t be, as what makes the most difference to someone’s quality of life is how they experience the world, how they experience life, not what other people insist it is actually like. Of course, we want to believe things will change for them, that they will get better, and most depressed people will. What does that mean about their right to say, as Ruth does, “my time, my place, my way,” or our right to intervene? One of the most insightful discussions I’ve heard about suicide since Owen’s death is an interview Hermione Lee did with Adam Phillips about his book On Giving Up. Phillips argues that we should be “able to acknowledge, not happily, that for some people, their lives are actually unbearable,” that the dogmatic insistence on life as the ultimate unassailable intrinsic good (what he calls “the ‘life is sacred’ line”) “means you are absolutely compelled to suffer whatever it is that’s inflicted on you,” which he rejects as an “intolerable position.” I agree, while recognizing as he does that this does not make any part of such a scenario anything other than heartbreaking, tragic. Phillips notes that the famous psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott never tried to dissuade anyone from suicide: “I just try to make sure they do it for the right reasons,” Winnicott said. I find that a defensible and principled position—but this is a case in which my head and my heart are in profound and perhaps intractable conflict.*

Is Ruth seeking death for the “right reasons”? I think Exit Lines ultimately answers this question in the negative, although I won’t go into spoilers about what exactly happens. I found the novel’s ending disappointing in some ways, because it seemed to falter from its own hard won and, to my mind, justifiable position. On the other hand, Barfoot’s characters do find comfort in the choice Ruth has fought for, in knowing that they do not have to “be helpless,” that “this could be a strong thing, although [they] did not dream of it before.” They feel better knowing that they do not have to drift passively into that good night but can stay in control, so that each day is really their own unless or until they choose otherwise. Planning for this eventuality gives them a long-term project “more riveting than playing bridge, watching TV or turning needles and wool, click, click click.” The tone of the ending, which is uplifting without being saccharine, is well suited to the book as a whole, which I have probably made sound much heavier going than it actually is. I began by describing it as “darkly comic” and it really is quite funny, and exceptionally clear-eyed about people’s weaknesses and hypocrisies and moral compromises. I really appreciated Barfoot’s ability to combine a brisk, entertaining story with such important questions about life and death. The book I read right after it, Elizabeth Berg’s Never Change, tries to do something similar—it is about someone with terminal cancer making decisions about the end of his life—but by comparison it seemed pat, simplistic, and emotionally manipulative.

It was Backlisted that made me go looking for something by Barfoot to read: their conversation about her earlier novel Gaining Ground (aka Abra) was completely convincing about the quality of the novel. Exit Lines is the only one of Barfoot’s novels held at the Halifax Public Libraries, which is why I got to it first, but it turns out the Dalhousie library has a lot of them, several of which I checked out on my last visit to the stacks. I don’t know why I hadn’t already read more of Barfoot’s fiction: I had certainly heard of her, and I think I actually read Dancing in the Dark many years ago, but somehow I had never gotten any further. I plan to make up for that in the next few weeks.

*I am not interested in debating the ethics of suicide here, or in defending either Owen’s choice or our understanding of it. I was recently reminded that this is a subject on which some people feel free to judge and criticize both the person who died and those who grieve them. Comments along those lines will be deleted.

In the clamor, Paula begins to paint, condenses the sum of the stories and the images into a single gesture, a movement sweeping as a lasso and precise as an arrow, since her painting contains at the moment something quite other than itself, gathers up the grazed knees of a five-year-old girl, the danger, an island in the far reaches of the Pacific, the sound of an egg hatching, the vanity of a king, a Portuguese sailor who bites into a rat, the rippling hair of a movie star, a writer gone fishing, the mass of time, and beneath embroidered swaddling clothes, a royal baby asleep, as if in a mythical nest, at the bottom of a shell.

From this point of view, Paula is just one more painter, a point that is particularly emphasized by the final section in which she is hired to help complete a reproduction of the caves at Lascaux. To do this work, and indeed any of the painting she undertakes across the novel, Paula has to submerge herself in other times and places, in materials and processes, a kind of subordination of the self. Maybe this is how the novel asks us to think about decorative painting: instead of the insistent idiosyncrasy of works by the ‘great masters,’ which endlessly and beautifully and vexingly foreground their styles and their selves—their individual preoccupations—Paula and the other graduates of the Institut de Peinture disappear into the wood grain, the marbling, the cracks in the faux stucco. This erasure of the self makes an odd underlay for a book that is structured as a Bildungsroman or a Kunstlerroman, implicitly challenging the way those familiar fictional models drive our sense of what gives a life meaning, or what constitutes greatness or success in art.

From this point of view, Paula is just one more painter, a point that is particularly emphasized by the final section in which she is hired to help complete a reproduction of the caves at Lascaux. To do this work, and indeed any of the painting she undertakes across the novel, Paula has to submerge herself in other times and places, in materials and processes, a kind of subordination of the self. Maybe this is how the novel asks us to think about decorative painting: instead of the insistent idiosyncrasy of works by the ‘great masters,’ which endlessly and beautifully and vexingly foreground their styles and their selves—their individual preoccupations—Paula and the other graduates of the Institut de Peinture disappear into the wood grain, the marbling, the cracks in the faux stucco. This erasure of the self makes an odd underlay for a book that is structured as a Bildungsroman or a Kunstlerroman, implicitly challenging the way those familiar fictional models drive our sense of what gives a life meaning, or what constitutes greatness or success in art. An interesting book, then—but not, for me, a very engrossing one. Still, I enjoyed sections like this, which appeal to my longstanding fascination with ‘neepery’:

An interesting book, then—but not, for me, a very engrossing one. Still, I enjoyed sections like this, which appeal to my longstanding fascination with ‘neepery’: Ruth sighs. It takes a great deal of energy, week after week, pressing her one remaining desire. “Try thinking of doneness as an awful illness then, and bound to be terminal. If you can’t even imagine feeling finished, you must think it’s a pretty terrible state to be in. So it’s about accepting what a person—me—regards as the end of the line. My definition of a fatal disease, which isn’t necessarily yours.”

Ruth sighs. It takes a great deal of energy, week after week, pressing her one remaining desire. “Try thinking of doneness as an awful illness then, and bound to be terminal. If you can’t even imagine feeling finished, you must think it’s a pretty terrible state to be in. So it’s about accepting what a person—me—regards as the end of the line. My definition of a fatal disease, which isn’t necessarily yours.” The others’ counterarguments are also not that robust. “God crops up,” but none of them is religious, or at least doctrinally secure, enough to insist that her plan is wrong or sinful. They are all in varying stages of physical decline, and the one certainty they share is that they will eventually leave the Idyll Inn the same way other residents have, their bodies whisked away as quickly and quietly as possible so as not to discourage the rest. Still, it’s one thing to die and another to kill yourself, or so they try to convince Ruth (“Those people who struggle to be alive. When we are safe and comfortable here—they feel their lives are precious even when they are so very difficult, but you do not feel your life is?” challenges Greta). Ruth is resolute, however, and finally, one by one, they come around. As Sylvia puts it after her own change of heart, “Whatever anyone says—lawyers, doctors, governments, religions, all those nincompoop moral busybodies that float around like weed seeds—we should be in charge of our own selves.”

The others’ counterarguments are also not that robust. “God crops up,” but none of them is religious, or at least doctrinally secure, enough to insist that her plan is wrong or sinful. They are all in varying stages of physical decline, and the one certainty they share is that they will eventually leave the Idyll Inn the same way other residents have, their bodies whisked away as quickly and quietly as possible so as not to discourage the rest. Still, it’s one thing to die and another to kill yourself, or so they try to convince Ruth (“Those people who struggle to be alive. When we are safe and comfortable here—they feel their lives are precious even when they are so very difficult, but you do not feel your life is?” challenges Greta). Ruth is resolute, however, and finally, one by one, they come around. As Sylvia puts it after her own change of heart, “Whatever anyone says—lawyers, doctors, governments, religions, all those nincompoop moral busybodies that float around like weed seeds—we should be in charge of our own selves.” Barfoot simplifies things for her characters by emphasizing Ruth’s clarity of mind and purpose: whether you find her desire to die more or less acceptable as a result is going to depend on your values, but it does, I think, help answer the question “who decides” in her favour. Illnesses like depression affect, perhaps distort, people’s perception of reality: it is harder to defer to their autonomy, then, although perhaps it shouldn’t be, as what makes the most difference to someone’s quality of life is how they experience the world, how they experience life, not what other people insist it is actually like. Of course, we want to believe things will change for them, that they will get better, and most depressed people will. What does that mean about their right to say, as Ruth does, “my time, my place, my way,” or our right to intervene? One of the most insightful discussions I’ve heard about suicide since Owen’s death is

Barfoot simplifies things for her characters by emphasizing Ruth’s clarity of mind and purpose: whether you find her desire to die more or less acceptable as a result is going to depend on your values, but it does, I think, help answer the question “who decides” in her favour. Illnesses like depression affect, perhaps distort, people’s perception of reality: it is harder to defer to their autonomy, then, although perhaps it shouldn’t be, as what makes the most difference to someone’s quality of life is how they experience the world, how they experience life, not what other people insist it is actually like. Of course, we want to believe things will change for them, that they will get better, and most depressed people will. What does that mean about their right to say, as Ruth does, “my time, my place, my way,” or our right to intervene? One of the most insightful discussions I’ve heard about suicide since Owen’s death is

I’m trying to get back in the habit of writing up most (maybe not all) of the books I read so here we go with a quickish update on two novels that I recently finished.

I’m trying to get back in the habit of writing up most (maybe not all) of the books I read so here we go with a quickish update on two novels that I recently finished. In contrast, I had never heard of Jazmina Barrera’s Cross Stitch when I first spotted it in the bookstore a couple of months ago. Its title caught my eye because I do cross stitch myself, though it has been a while since I picked up any of my works in progress. (As my eyes age,

In contrast, I had never heard of Jazmina Barrera’s Cross Stitch when I first spotted it in the bookstore a couple of months ago. Its title caught my eye because I do cross stitch myself, though it has been a while since I picked up any of my works in progress. (As my eyes age,

Ah, those days . . . for many years afterwards their happiness haunted me. Sometimes, listening to music, I drift back and nothing has changed. The long end of summer. Day after day of warm weather, voices calling as night came on and lighted windows pricked the darkness and, at day-break, the murmur of corn and the warm smell of hayfields ripe for harvest. And being young.

Ah, those days . . . for many years afterwards their happiness haunted me. Sometimes, listening to music, I drift back and nothing has changed. The long end of summer. Day after day of warm weather, voices calling as night came on and lighted windows pricked the darkness and, at day-break, the murmur of corn and the warm smell of hayfields ripe for harvest. And being young. Throughout the novel there is a neat but never pat association between the restoration of the mural and Tom’s reconnection with a world full of life and colour—and along the way we get to follow Tom’s growing excitement about the painting itself, which he comes to believe is a true masterpiece:

Throughout the novel there is a neat but never pat association between the restoration of the mural and Tom’s reconnection with a world full of life and colour—and along the way we get to follow Tom’s growing excitement about the painting itself, which he comes to believe is a true masterpiece: June began slowly, as a reading month anyway, as I was in Vancouver for the first 10 days of it and, as is pretty typical on these trips, I was too busy to settle down with a book. I did read about half of John Vaillant’s The Golden Spruce on the plane, and most of Donna Leon’s Drawing Conclusions while I was there (I borrowed it from my parents’ well-stocked mystery shelves but did not manage to finish it before I left). I’m definitely not complaining! It was a cheerful visit, made more so because Maddie was with me and I loved sharing my favorite people and places with her. Because we were also sharing a suitcase, I was also very restrained and did not buy any books while I was there. The only one I acquired was a very cool gift from my mother: a second impression of the first edition of The Waves

June began slowly, as a reading month anyway, as I was in Vancouver for the first 10 days of it and, as is pretty typical on these trips, I was too busy to settle down with a book. I did read about half of John Vaillant’s The Golden Spruce on the plane, and most of Donna Leon’s Drawing Conclusions while I was there (I borrowed it from my parents’ well-stocked mystery shelves but did not manage to finish it before I left). I’m definitely not complaining! It was a cheerful visit, made more so because Maddie was with me and I loved sharing my favorite people and places with her. Because we were also sharing a suitcase, I was also very restrained and did not buy any books while I was there. The only one I acquired was a very cool gift from my mother: a second impression of the first edition of The Waves , from the Hogarth Press.

, from the Hogarth Press.  , that while all of its detail about the history and processes of the lumber industry in BC were interesting enough, the book also gave the impression of a single man’s story elaborated or built up with background and contexts until it made a large enough whole. Sometimes I just wanted to get on with the actual events!

, that while all of its detail about the history and processes of the lumber industry in BC were interesting enough, the book also gave the impression of a single man’s story elaborated or built up with background and contexts until it made a large enough whole. Sometimes I just wanted to get on with the actual events!

On the approach to Richmond, they passed a sign, a large board with a map of the path they were following, the scrawled red line from west coast to east, an arrow two-thirds of the way across labelled ‘You Are Here’.

On the approach to Richmond, they passed a sign, a large board with a map of the path they were following, the scrawled red line from west coast to east, an arrow two-thirds of the way across labelled ‘You Are Here’. The other clever thing about You Are Here is how neatly the walking trip fits the underlying movement of both plot and character: that it’s obvious (in a novel, a literal journey is pretty much always also a metaphorical journey) doesn’t make it dull, and the gradual progress of our protagonists towards tolerance, then interest, then understanding, then liking, then affection as they trudge and clamber and stroll towards each new stopping point is well done. Even though it seemed pretty clear what their final destination was, the route they take to get there is not, unlike the literal journey, mapped out ahead of time, and it was satisfying arrivingthere with them after the requisite Big Misunderstanding.

The other clever thing about You Are Here is how neatly the walking trip fits the underlying movement of both plot and character: that it’s obvious (in a novel, a literal journey is pretty much always also a metaphorical journey) doesn’t make it dull, and the gradual progress of our protagonists towards tolerance, then interest, then understanding, then liking, then affection as they trudge and clamber and stroll towards each new stopping point is well done. Even though it seemed pretty clear what their final destination was, the route they take to get there is not, unlike the literal journey, mapped out ahead of time, and it was satisfying arrivingthere with them after the requisite Big Misunderstanding.

Book blogging was easier, somehow, when I just wrote up every book I read as soon as I finished it. I was so much busier in other respects when I adopted that habit: looking back, I have now idea how I found the time for it. But one plausible theory is that I saved a lot of time not dithering about blogging! Just do it – good advice for so many things, including writing.

Book blogging was easier, somehow, when I just wrote up every book I read as soon as I finished it. I was so much busier in other respects when I adopted that habit: looking back, I have now idea how I found the time for it. But one plausible theory is that I saved a lot of time not dithering about blogging! Just do it – good advice for so many things, including writing. The novel’s non-stop melodrama is in service of a worldview, or an idea about human desires and instincts. I think possibly this sentence is key: “The door of terror opened over the black chasm of sex, love even unto death, destruction for fuller possession.” I hope the One Bright Pod folks (whose fault it is that I read this) will tell me if there is some kind of link to D. H. Lawrence here: it seems so to me, but I don’t know Lawrence well enough to be sure. I also hope they talk about what trains signify and how they are used in the novel. They are clearly (I think) symbols of modernity, but there is a lot more going on with them, especially the engine personified by one of the characters as a woman (“she” is perhaps his most genuinely caring relationship). Once I’d

The novel’s non-stop melodrama is in service of a worldview, or an idea about human desires and instincts. I think possibly this sentence is key: “The door of terror opened over the black chasm of sex, love even unto death, destruction for fuller possession.” I hope the One Bright Pod folks (whose fault it is that I read this) will tell me if there is some kind of link to D. H. Lawrence here: it seems so to me, but I don’t know Lawrence well enough to be sure. I also hope they talk about what trains signify and how they are used in the novel. They are clearly (I think) symbols of modernity, but there is a lot more going on with them, especially the engine personified by one of the characters as a woman (“she” is perhaps his most genuinely caring relationship). Once I’d  The other three books I’ve finished are Mollie Keane’s Good Behaviour (didn’t much like it, though I could see how skillful it is), Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans (found it boring even though I knew he was doing his withholding / unreliable narrator trick again so I knew that if I only understood what lay beneath the boring layer, it would be much more interesting – this is a risk he takes repeatedly, as I discussed in

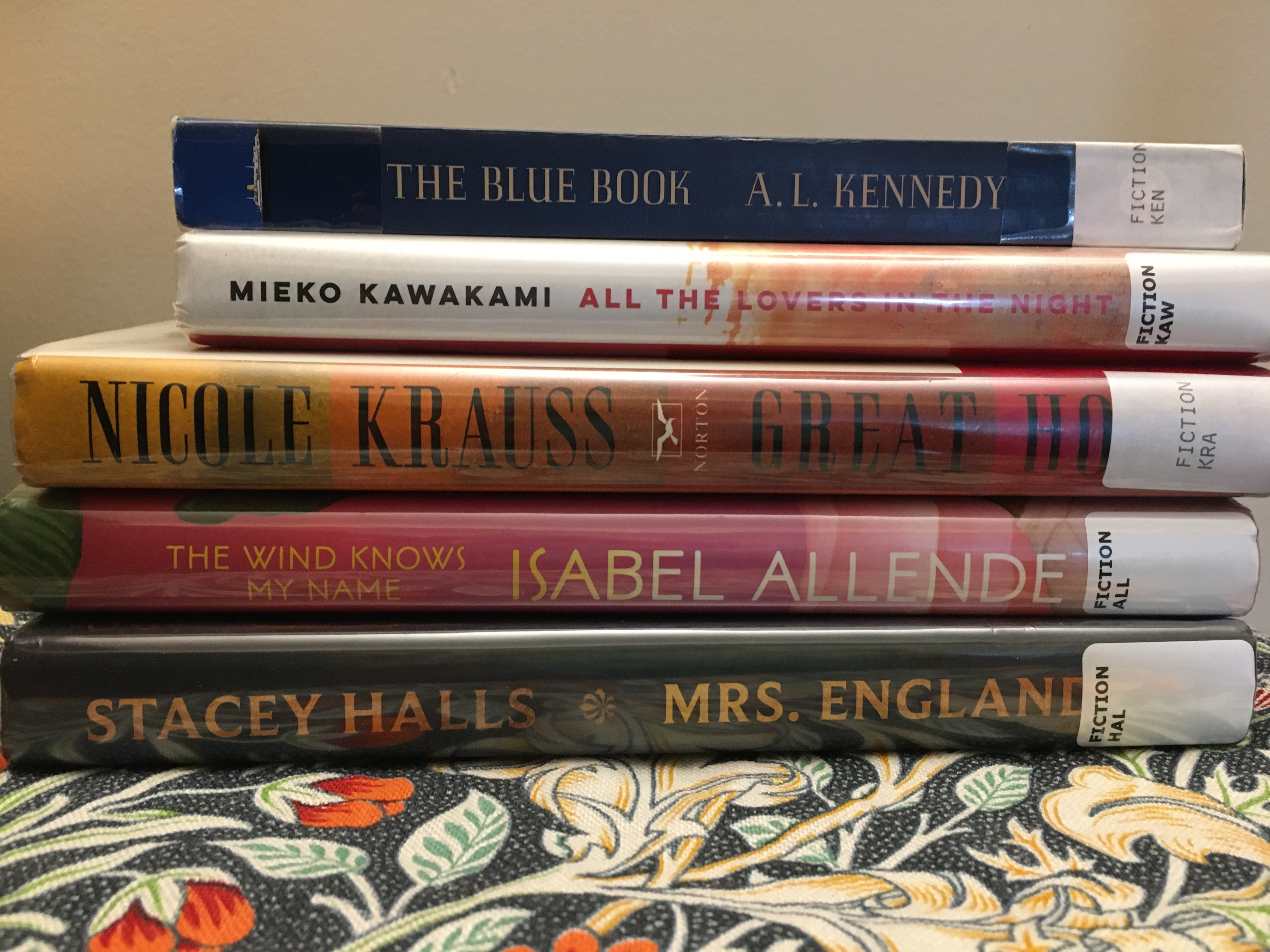

The other three books I’ve finished are Mollie Keane’s Good Behaviour (didn’t much like it, though I could see how skillful it is), Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans (found it boring even though I knew he was doing his withholding / unreliable narrator trick again so I knew that if I only understood what lay beneath the boring layer, it would be much more interesting – this is a risk he takes repeatedly, as I discussed in  What’s next, you wonder? Maybe Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts, which I picked up recently with a birthday gift card (thank you!), or something from my miscellaneous stack of library books. Living so close to the public library has made me pretty casual about taking things out that I may or may not commit to reading: I like having options! (If there’s anything there you think I should definitely try, let me know.) I also have Cold Comfort Farm to hand, which was my ‘Independent Bookstore Day’ treat – but I’m saving it to read on the plane when I go to Vancouver in a couple of weeks.

What’s next, you wonder? Maybe Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts, which I picked up recently with a birthday gift card (thank you!), or something from my miscellaneous stack of library books. Living so close to the public library has made me pretty casual about taking things out that I may or may not commit to reading: I like having options! (If there’s anything there you think I should definitely try, let me know.) I also have Cold Comfort Farm to hand, which was my ‘Independent Bookstore Day’ treat – but I’m saving it to read on the plane when I go to Vancouver in a couple of weeks. April hasn’t been a bad month for reading, overall. I’ve already written up Dorothy B. Hughes’s

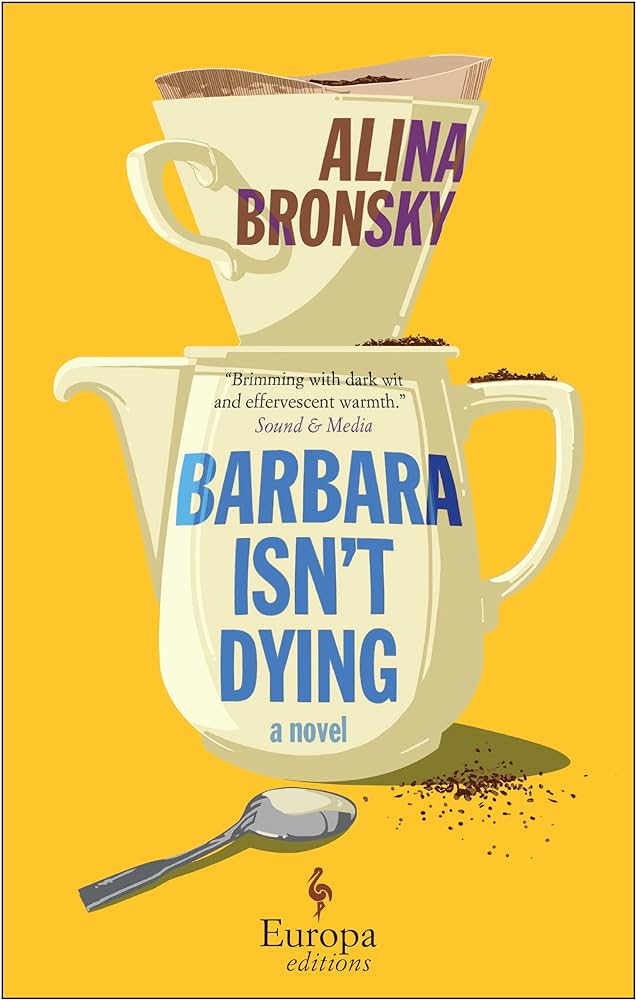

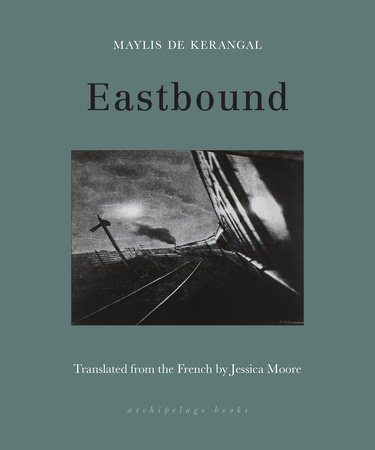

April hasn’t been a bad month for reading, overall. I’ve already written up Dorothy B. Hughes’s  I read Maylis De Kerangal’s Eastbound in one sitting, not just because it’s short but because it’s very suspenseful and I really wanted to find out what happened! I ended up thinking that the novel’s success in this respect worked against the quality of my reading of it, because I didn’t linger over the aspects of the novel that make it more than just a thriller. The story is very simple: a young Russian soldier on a train to Siberia decides to go AWOL and is helped in his attempted escape by another passenger, a young French woman. Will he succeed, or will he be discovered and pay the price? Anxious to know, I paid less attention than I should have to the descriptions of the landscape scrolling past them – though I did appreciate them, I didn’t really think about them, and a reread of the novel would probably show me more metaphorical and historical layers to the characters’ journey. Some other time, maybe, as I had to return my copy to the library! But even my brisk reading showed me why

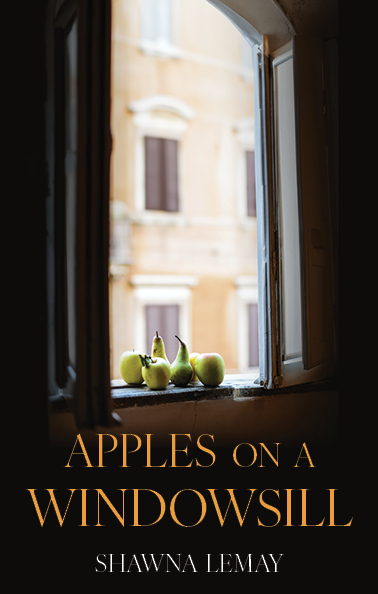

I read Maylis De Kerangal’s Eastbound in one sitting, not just because it’s short but because it’s very suspenseful and I really wanted to find out what happened! I ended up thinking that the novel’s success in this respect worked against the quality of my reading of it, because I didn’t linger over the aspects of the novel that make it more than just a thriller. The story is very simple: a young Russian soldier on a train to Siberia decides to go AWOL and is helped in his attempted escape by another passenger, a young French woman. Will he succeed, or will he be discovered and pay the price? Anxious to know, I paid less attention than I should have to the descriptions of the landscape scrolling past them – though I did appreciate them, I didn’t really think about them, and a reread of the novel would probably show me more metaphorical and historical layers to the characters’ journey. Some other time, maybe, as I had to return my copy to the library! But even my brisk reading showed me why  My current reading is Shawna Lemay’s Apples on a Windowsill, which is (more or less) about still lifes as a genre, but which roams across a range of topics in a thoughtful and often beautifully meditative way. A sample:

My current reading is Shawna Lemay’s Apples on a Windowsill, which is (more or less) about still lifes as a genre, but which roams across a range of topics in a thoughtful and often beautifully meditative way. A sample:

Another car would have come along, a family car for which she had said she was waiting, or even another man, a white man. Most travelers, like most men, were intrinsically decent. The end result for Iris would have been the same, cruelly the same. But he needn’t have been involved. He was the wrong man to have played Samaritan, and he’d known it, known it there on the road and in every irreversible moment since.

Another car would have come along, a family car for which she had said she was waiting, or even another man, a white man. Most travelers, like most men, were intrinsically decent. The end result for Iris would have been the same, cruelly the same. But he needn’t have been involved. He was the wrong man to have played Samaritan, and he’d known it, known it there on the road and in every irreversible moment since. There are many interesting aspects of the investigation that unfolds as Hugh (with painful inevitability) ends up the prime suspect in Iris’s death. I haven’t spent enough time with the novel at this point to be sure what to make of all of them, but one thing I’ll want to think more about is Ellen’s role, which doesn’t fit any of the usual restrictive hard-boiled parts for women to play. It seems tied to the novel’s attention to class, which, as Mosley notes in his Afterword to the NYRB edition, does not protect Hugh the way he hopes it will: his education and career path, his family’s money and social standing—none of it insulates him from hatred or suspicion. But Ellen’s money and connections are sources of strength, as is her prompt and unequivocal commitment to being on Hugh’s side. If Iris can be seen as a version of the damsel-in-distress turned femme fatale (intentionally or not), Ellen is an ally and partner for Hugh, one who refuses to sit on the sidelines while an injustice is perpetrated. There are other details worth considering about who helps Hugh and who doesn’t, too, including the white lawyer whose motives are primarily political, rather than principled.

There are many interesting aspects of the investigation that unfolds as Hugh (with painful inevitability) ends up the prime suspect in Iris’s death. I haven’t spent enough time with the novel at this point to be sure what to make of all of them, but one thing I’ll want to think more about is Ellen’s role, which doesn’t fit any of the usual restrictive hard-boiled parts for women to play. It seems tied to the novel’s attention to class, which, as Mosley notes in his Afterword to the NYRB edition, does not protect Hugh the way he hopes it will: his education and career path, his family’s money and social standing—none of it insulates him from hatred or suspicion. But Ellen’s money and connections are sources of strength, as is her prompt and unequivocal commitment to being on Hugh’s side. If Iris can be seen as a version of the damsel-in-distress turned femme fatale (intentionally or not), Ellen is an ally and partner for Hugh, one who refuses to sit on the sidelines while an injustice is perpetrated. There are other details worth considering about who helps Hugh and who doesn’t, too, including the white lawyer whose motives are primarily political, rather than principled. The thing that does make me hesitate is the oddity (arguably) of assigning a novel that is fundamentally about race, and that is told from the point of view of a Black man—but which is written by a white woman. “A white woman writing of a young black man’s problems with the law was a certain kind of gamble,” Mosley comments in his Afterword—but Mosley himself doesn’t seem to consider it problematic, moving immediately on to remark Hughes’s general interest in writing “from perspectives far from her own.” It is clear from the afterword that Mosley greatly admires Hughes in general and The Expendable Man in particular. What kind of representation is more important, in a class like mine that tries to show the range of uses to which the forms of detective fiction have been put since its emergence as a distinct form? It seems as if Mosley would consider it most important to address “the darker reality” (as he puts it) that lies behind more “glittering versions of American life.” Presumably he thinks the gamble paid off for Hughes because the result was a very good novel.

The thing that does make me hesitate is the oddity (arguably) of assigning a novel that is fundamentally about race, and that is told from the point of view of a Black man—but which is written by a white woman. “A white woman writing of a young black man’s problems with the law was a certain kind of gamble,” Mosley comments in his Afterword—but Mosley himself doesn’t seem to consider it problematic, moving immediately on to remark Hughes’s general interest in writing “from perspectives far from her own.” It is clear from the afterword that Mosley greatly admires Hughes in general and The Expendable Man in particular. What kind of representation is more important, in a class like mine that tries to show the range of uses to which the forms of detective fiction have been put since its emergence as a distinct form? It seems as if Mosley would consider it most important to address “the darker reality” (as he puts it) that lies behind more “glittering versions of American life.” Presumably he thinks the gamble paid off for Hughes because the result was a very good novel.