2016 has been a somewhat unusual reading year for me because quite a few of the books I read were ‘assigned’ for reviews — or else were books I chose not entirely because I wanted to read them but because they looked like books I could pitch for reviews. Although at times I ended up feeling a bit stifled as a result, because it felt as if reading obligations were crowding out reading pleasures, at other times it meant a thrill of discovery, as a book or author I wouldn’t otherwise have read turned out to be wonderful. This was also a sign that as a writer I was being pushed in new directions and, as a result, learning new skills and finding (I hope) new strengths — about which, more in my next post on my year in writing!

2016 has been a somewhat unusual reading year for me because quite a few of the books I read were ‘assigned’ for reviews — or else were books I chose not entirely because I wanted to read them but because they looked like books I could pitch for reviews. Although at times I ended up feeling a bit stifled as a result, because it felt as if reading obligations were crowding out reading pleasures, at other times it meant a thrill of discovery, as a book or author I wouldn’t otherwise have read turned out to be wonderful. This was also a sign that as a writer I was being pushed in new directions and, as a result, learning new skills and finding (I hope) new strengths — about which, more in my next post on my year in writing!

Looking back on 2016, here are some of the books that stand out.

Book of the Year: Moby-Dick. Really, how could it not be? I’m not saying I read it particularly well, but hey — it was my first time! And I read it with a great deal more pleasure than I expected, and also a sense of expanding horizons. Yes, it’s about whales, the way War and Peace is about Russia — it’s not only about so much more but it just does so much more that’s surprising and amazing and, yes, occasionally tedious, or just plain baffling. I was just reading an earnest article about the importance of revising and revising and revising to perfect every last word: though I don’t actually know what Melville’s own writing process was, it seems to me that this is the kind of well-intentioned advice for novelists about their “craft” that yields books as impeccable but somehow lifeless as Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena while guaranteeing us no more fearless Moby-Dick-like masterpieces.

Book of the Year: Moby-Dick. Really, how could it not be? I’m not saying I read it particularly well, but hey — it was my first time! And I read it with a great deal more pleasure than I expected, and also a sense of expanding horizons. Yes, it’s about whales, the way War and Peace is about Russia — it’s not only about so much more but it just does so much more that’s surprising and amazing and, yes, occasionally tedious, or just plain baffling. I was just reading an earnest article about the importance of revising and revising and revising to perfect every last word: though I don’t actually know what Melville’s own writing process was, it seems to me that this is the kind of well-intentioned advice for novelists about their “craft” that yields books as impeccable but somehow lifeless as Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena while guaranteeing us no more fearless Moby-Dick-like masterpieces.

Runners-Up:

Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth and Henry James, The Portrait of a Lady. Together with Daniel Deronda, these make a remarkable trilogy of variations on a theme. Each of them features a young woman of great intelligence and high spirits hemmed in on every side by social and personal contexts that deny her suitable outlets for her energy. My love-hate relationship with James’s prose continues; Wharton, on the other hand, proved much more congenial, and I’ve got The Custom of the Country on my list of books to read in 2017.

Other Highlights:

Inspired in part by The Portrait of a Lady, I finally read Colm Tóibín’s The Master — and loved it. I’d put it off because I was so underwhelmed with Brooklyn (an impression that was basically confirmed when, inspired by The Master, I reread it), but The Master is artful and tender and brilliant. I expect it’s even better to a true Jamesian, who would get all the subtle allusions and nuances, but it’s a sign of Tóibín’s skill that even a James-skeptic like myself could become totally absorbed in his character.

Inspired in part by The Portrait of a Lady, I finally read Colm Tóibín’s The Master — and loved it. I’d put it off because I was so underwhelmed with Brooklyn (an impression that was basically confirmed when, inspired by The Master, I reread it), but The Master is artful and tender and brilliant. I expect it’s even better to a true Jamesian, who would get all the subtle allusions and nuances, but it’s a sign of Tóibín’s skill that even a James-skeptic like myself could become totally absorbed in his character.

I loved David Ebershoff’s The Danish Girl. Above all, it is a story about the kind of love and acceptance we all dream of, but it’s also about art and beauty and identity, about how we see ourselves and each other.

A friend recommended Kent Haruf’s Plainsong and I’m so glad she did: I ended up reading three of his novels and being touched and impressed by all of them. I think Plainsong is the best (most complex, most ambitious) of them, but my personal favorite was Our Souls At Night: something about its evocation of loneliness, and the delicacy with which it explores the possibility of overcoming it, really spoke to me.

Another author I discovered thanks to a prompt from someone else was David Constantine: Scott Esposito asked me to review The Life-Writer and In Another Country for The Quarterly Conversation, and as he predicted I was really impressed. Constantine is a writer’s writer, meticulous and nuanced, but like Alice Munro he embeds both plot twists and emotional surprises into his understated but beautiful prose.

Another author I discovered thanks to a prompt from someone else was David Constantine: Scott Esposito asked me to review The Life-Writer and In Another Country for The Quarterly Conversation, and as he predicted I was really impressed. Constantine is a writer’s writer, meticulous and nuanced, but like Alice Munro he embeds both plot twists and emotional surprises into his understated but beautiful prose.

I read Andrea Levy’s Small Island soon after the U.S. election, and it turned out to be unexpectedly timely and somewhat comforting in the tenderness with which it shows disparate people doing their best to live together.

With an eye to my upcoming ‘pulp fiction’ class, I dipped into westerns, a genre I previously knew almost nothing about. I sampled quite a few but the only ones I read attentively all the way through were Charles Portis’s True Grit and Elmore Leonard’s Valdez is Coming. I enjoyed them both thoroughly, but I can’t really see myself reading many more westerns for my own pleasure: reading about them will probably do. Lonesome Dove, maybe? And speaking of genre fiction, I read some good new crime novels this year too, including Phonse Jessome’s gritty Halifax noir Disposable Souls and Maurizio de Giovanni’s Bastards of Pizzofalcone books.

Finally, Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals was an absolute tonic as this rather depressing year drew to its close. And one more last-minute success was Danielle Dutton’s Margaret the First, which turned out to be a small, glittering jewel of a novel. (My review will be out in the TLS early in 2017.)

Finally, Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals was an absolute tonic as this rather depressing year drew to its close. And one more last-minute success was Danielle Dutton’s Margaret the First, which turned out to be a small, glittering jewel of a novel. (My review will be out in the TLS early in 2017.)

Low Points:

This is 100% about a failure on my part, and also my own disappointment — with myself, though also (however irrationally) with the novel: I tried and failed to read To the Lighthouse. I did read it, in the sense of turning every page, but I could not seem to find the novel I knew was in there somewhere, waiting to transform me. I will try again, after a decent interval.

Curtis Sittenfeld’s Ineligible made me swear off Austen pastiches forever. And I vehemently disliked Dinitia Smith’s The Honeymoon, which I reviewed for the TLS. I saw another novel about George Eliot in the bookstore not long ago and shuddered away from it: though it would be nice to be pleasantly surprised, I have yet to read a really good example of this particular species.

Ian McEwan’s Nutshell was the worst book I may ever have read by an author I fervently admire.

Not Reading, Exactly, But:

I finished my first full viewing of both Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel this year. I’ve been rewatching both shows intermittently ever since, which tells you a lot about how interested I got in them. It also indicates something that those who’d seen both series before already knew: both reward rewatching (which is a kind of reading, really) more than many television shows: they reveal layers and connections and themes that aren’t always obvious at first when you’re caught up in the immediate drama. Even when I found the particulars absurd, which did occasionally happen (maybe more for me than for people who are more at home in fantasy as a genre), I never stopped caring about the characters, and now that I’ve seen how all the story arcs turn out, I’m finding myself even more emotionally involved with them.

I finished my first full viewing of both Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel this year. I’ve been rewatching both shows intermittently ever since, which tells you a lot about how interested I got in them. It also indicates something that those who’d seen both series before already knew: both reward rewatching (which is a kind of reading, really) more than many television shows: they reveal layers and connections and themes that aren’t always obvious at first when you’re caught up in the immediate drama. Even when I found the particulars absurd, which did occasionally happen (maybe more for me than for people who are more at home in fantasy as a genre), I never stopped caring about the characters, and now that I’ve seen how all the story arcs turn out, I’m finding myself even more emotionally involved with them.

My 2017 TBR List:

There are a lot of books I look forward to reading in 2017, including (as already mentioned), more Edith Wharton. I have David Ebershoff’s The 19th Wife standing by, along with volumes 2 and 3 in Jane Smiley’s “Last 100 Years” trilogy. In the same stack is Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, partly because of my questions about My Name Is Lucy Barton and minimalism in fiction, and partly just because; Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing With Feathers is there too, and Sarah Moss’s Body of Light, and China Mieville’s The City and the City. My success with Moby-Dick has had me wondering if I should stop being scared of Ulysses and give it a try in 2017. Part of what’s exciting about a new year, though, is not knowing yet what great books lie in wait that I haven’t even thought of reading yet!

Lovely as Durrell’s scenery is, he’s at his best (as you’d expect) with animals:

Lovely as Durrell’s scenery is, he’s at his best (as you’d expect) with animals: Perhaps, then, the child’s point of view (though of course the sophistication of the writing subtly belies it) is one reason children have loved this book. Another would be its humor: when things do happen, they are usually very funny. There’s some high drama, as well: the epic battle, for example, between the gecko Geronimo and the giant mantid Cicely:

Perhaps, then, the child’s point of view (though of course the sophistication of the writing subtly belies it) is one reason children have loved this book. Another would be its humor: when things do happen, they are usually very funny. There’s some high drama, as well: the epic battle, for example, between the gecko Geronimo and the giant mantid Cicely: In case you were wondering why it has been so quiet here at Novel Readings, I’ve been grading papers industriously, trying to get through them as efficiently as I could consistent with still paying really close attention. I did well at sticking with it, partly thanks to my students, many of whom wrote really good essays! Not only does that speed things up, but it makes the whole process more enjoyable.

In case you were wondering why it has been so quiet here at Novel Readings, I’ve been grading papers industriously, trying to get through them as efficiently as I could consistent with still paying really close attention. I did well at sticking with it, partly thanks to my students, many of whom wrote really good essays! Not only does that speed things up, but it makes the whole process more enjoyable. Before I put this term completely behind me, though, one question lingers after hours spent poring over student writing: what’s up with apostrophes? Actually, I have two questions, because my follow-up to that one is, should I care about apostrophes?

Before I put this term completely behind me, though, one question lingers after hours spent poring over student writing: what’s up with apostrophes? Actually, I have two questions, because my follow-up to that one is, should I care about apostrophes?

I’ve just finished two Scottish-themed romance novels — Sarah MacLean’s A Scot in the Dark and Tessa Dare’s When a Scot Ties the Knot — and they have enough similarities that the juxtaposition has provoked me to figure out why I enjoyed one so much more than the other, a question that quickly expanded, in my mind, to the more general question of why some romance novels work for me and others just don’t, including novels by the same authors. Of these two, for instance, I much preferred Dare’s, though I really enjoyed The Rogue Not Taken, the previous novel in MacLean’s “Scandal & Scoundrel” series, and I liked but didn’t love Dare’s most recent novel, Do You Want to Start a Scandal.

I’ve just finished two Scottish-themed romance novels — Sarah MacLean’s A Scot in the Dark and Tessa Dare’s When a Scot Ties the Knot — and they have enough similarities that the juxtaposition has provoked me to figure out why I enjoyed one so much more than the other, a question that quickly expanded, in my mind, to the more general question of why some romance novels work for me and others just don’t, including novels by the same authors. Of these two, for instance, I much preferred Dare’s, though I really enjoyed The Rogue Not Taken, the previous novel in MacLean’s “Scandal & Scoundrel” series, and I liked but didn’t love Dare’s most recent novel, Do You Want to Start a Scandal. For instance, I have mentioned before that I don’t always read right to the end of the HEA. This is partly because while I can enjoy the development of a romantic relationship, especially when it involves witty sparring and plenty of sexual tension, I don’t find unmitigated happiness (which is where, of course, romance novels always end up, sooner or later) that dramatically interesting. But it’s also because I don’t really believe marriage itself is necessarily a particularly blissful state. For both of these reasons, the rosier things get for the protagonists, the more disengaged I become from their novel. Thus I usually prefer romances that defer the protagonists’ happiness until the end of the novel, or very nearly. In a lot of Georgette Heyer’s novels, for example, hero and heroine don’t come joyfully together until pretty much the last page. That keeps things interesting! Our attention then is also less on how delightful they find each other and more on their learning about each other, and / or on wondering how they will ever discover how delightful they are to each other, or on how they will overcome the personal or social obstacles keeping them apart.

For instance, I have mentioned before that I don’t always read right to the end of the HEA. This is partly because while I can enjoy the development of a romantic relationship, especially when it involves witty sparring and plenty of sexual tension, I don’t find unmitigated happiness (which is where, of course, romance novels always end up, sooner or later) that dramatically interesting. But it’s also because I don’t really believe marriage itself is necessarily a particularly blissful state. For both of these reasons, the rosier things get for the protagonists, the more disengaged I become from their novel. Thus I usually prefer romances that defer the protagonists’ happiness until the end of the novel, or very nearly. In a lot of Georgette Heyer’s novels, for example, hero and heroine don’t come joyfully together until pretty much the last page. That keeps things interesting! Our attention then is also less on how delightful they find each other and more on their learning about each other, and / or on wondering how they will ever discover how delightful they are to each other, or on how they will overcome the personal or social obstacles keeping them apart. I also often find with more recent romances that the protagonists get intimately sexy too soon and too often for my taste. I don’t think this means I’m prudish! No doubt it’s partly the result of many years spent reading Victorian novels, which are full of erotic undercurrents but have vanishingly few explicitly sexual moments. When feelings (and body parts) are usually kept covered, it’s that much more exciting when you finally get a glimpse! As well, I don’t think lust and love are the same thing, and sometimes — including in A Scot in the Dark — they get too quickly conflated. I suppose this is a variation on my preference for deferring their happiness, and it’s also about the sacrifice of tension involved. (I think there may also be some problems with realism — but I’m really not an expert on sexual mores during the Regency, so I may be quite wrong about what well bred men and young, “respectable,” unmarried women would get up to in their carriages without anxiety, shame, or repercussions.)

I also often find with more recent romances that the protagonists get intimately sexy too soon and too often for my taste. I don’t think this means I’m prudish! No doubt it’s partly the result of many years spent reading Victorian novels, which are full of erotic undercurrents but have vanishingly few explicitly sexual moments. When feelings (and body parts) are usually kept covered, it’s that much more exciting when you finally get a glimpse! As well, I don’t think lust and love are the same thing, and sometimes — including in A Scot in the Dark — they get too quickly conflated. I suppose this is a variation on my preference for deferring their happiness, and it’s also about the sacrifice of tension involved. (I think there may also be some problems with realism — but I’m really not an expert on sexual mores during the Regency, so I may be quite wrong about what well bred men and young, “respectable,” unmarried women would get up to in their carriages without anxiety, shame, or repercussions.) A specific romance-reading preference of mine that I know is about me more than about the novels is that I have a fondness for bluestocking heroines, or at least ones with an intellectual passion, who have a lot more on their minds than romance. I love Dare’s A Week to be Wicked and Courtney Milan’s The Countess Conspiracy for this reason, and of course my favorite romance of all — so far — is Loretta Chase’s Mr. Impossible. Madeline in When a Scot Ties the Knot, with her passion for illustrating natural history, is a good addition to this collection. I also prefer more mature heroines, and I have a fondness for prickly ones, like Claudia Martin in Mary Balogh’s Simply Perfect. I find ingenues annoying and get bored easily by heroines who are too nice. It’s not hard to see that I appreciate romance novels that show women at least somewhat like me as lovable!

A specific romance-reading preference of mine that I know is about me more than about the novels is that I have a fondness for bluestocking heroines, or at least ones with an intellectual passion, who have a lot more on their minds than romance. I love Dare’s A Week to be Wicked and Courtney Milan’s The Countess Conspiracy for this reason, and of course my favorite romance of all — so far — is Loretta Chase’s Mr. Impossible. Madeline in When a Scot Ties the Knot, with her passion for illustrating natural history, is a good addition to this collection. I also prefer more mature heroines, and I have a fondness for prickly ones, like Claudia Martin in Mary Balogh’s Simply Perfect. I find ingenues annoying and get bored easily by heroines who are too nice. It’s not hard to see that I appreciate romance novels that show women at least somewhat like me as lovable! We had our last day of classes yesterday. Owing to a very peculiar scheduling plan devised (of course) by a committee, although yesterday was actually a Tuesday, it was designated an “extra Monday” to make up for “losing” a day of Monday classes to Thanksgiving (so much for the concept of a day off — must everything be weighed and measured?). Anyway, that meant two days of Monday classes in a row to bring us to the end of term. As I am not giving final exams in my courses, I now have a lull in immediately pressing teaching-related activities until the final essays come in, the first batch on Friday, the second on Sunday. Then I have to dig in and get through them all, and then do all the final record keeping so that I can compute and submit final grades.

We had our last day of classes yesterday. Owing to a very peculiar scheduling plan devised (of course) by a committee, although yesterday was actually a Tuesday, it was designated an “extra Monday” to make up for “losing” a day of Monday classes to Thanksgiving (so much for the concept of a day off — must everything be weighed and measured?). Anyway, that meant two days of Monday classes in a row to bring us to the end of term. As I am not giving final exams in my courses, I now have a lull in immediately pressing teaching-related activities until the final essays come in, the first batch on Friday, the second on Sunday. Then I have to dig in and get through them all, and then do all the final record keeping so that I can compute and submit final grades. Though the cessation of classes doesn’t mean there’s not anything else to do at work (just for instance, today I put some time in organizing the Brightspace site and readings for one of next term’s courses), I usually take advantage of any break in the schedule at this time of year to get some holiday shopping done, especially for things I want to mail out west to my family. I was especially motivated to get as much done as I could today because so far (unlike my family out west, in a rare reversal!) we have no snow to deal with yet. Sadly, that can’t last, and everything gets harder once the roads and sidewalks are wintry. So once I’d taken care of some business at the office, out I went, and had a pretty nice time puttering around at the mall and in the rather more interesting shops at the

Though the cessation of classes doesn’t mean there’s not anything else to do at work (just for instance, today I put some time in organizing the Brightspace site and readings for one of next term’s courses), I usually take advantage of any break in the schedule at this time of year to get some holiday shopping done, especially for things I want to mail out west to my family. I was especially motivated to get as much done as I could today because so far (unlike my family out west, in a rare reversal!) we have no snow to deal with yet. Sadly, that can’t last, and everything gets harder once the roads and sidewalks are wintry. So once I’d taken care of some business at the office, out I went, and had a pretty nice time puttering around at the mall and in the rather more interesting shops at the

But in fact it’s not always true that I don’t like “spare” novels. I read three of Kent Haruf’s novels recently, and the sparest of them all,

But in fact it’s not always true that I don’t like “spare” novels. I read three of Kent Haruf’s novels recently, and the sparest of them all,

Marilyn’s mother tries to talk her out of marrying James. “Think about your children,” she urges Marilyn; “Where will you live? You won’t fit in anywhere.” James and Marilyn believe they can — even in the small Ohio town where they settle and where their children Nath, Lydia, and Hannah are born and grow up. The children don’t really fit in, however, though they hide the truth, concealing their isolation and trying to placate the parental unease that, in the guise of loving concern, infects every aspect of their life. The burden of her parents’ hopes falls especially hard on Lydia: nothing is ever proffered that isn’t tainted with expectations that “drifted and settled and crushed you with their weight.” It’s because she loves her parents and wants them to be happy that she accepts, over and over, all the things they want for her that she does not want for herself. Only when it’s too late does Marilyn realize what this acceptance has meant to Lydia, who never told her because she never could.

Marilyn’s mother tries to talk her out of marrying James. “Think about your children,” she urges Marilyn; “Where will you live? You won’t fit in anywhere.” James and Marilyn believe they can — even in the small Ohio town where they settle and where their children Nath, Lydia, and Hannah are born and grow up. The children don’t really fit in, however, though they hide the truth, concealing their isolation and trying to placate the parental unease that, in the guise of loving concern, infects every aspect of their life. The burden of her parents’ hopes falls especially hard on Lydia: nothing is ever proffered that isn’t tainted with expectations that “drifted and settled and crushed you with their weight.” It’s because she loves her parents and wants them to be happy that she accepts, over and over, all the things they want for her that she does not want for herself. Only when it’s too late does Marilyn realize what this acceptance has meant to Lydia, who never told her because she never could. You never know what twists of fate will bring new relevance to the readings you’ve assigned. Teaching A Room of One’s Own soon after the

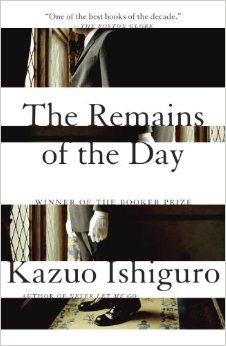

You never know what twists of fate will bring new relevance to the readings you’ve assigned. Teaching A Room of One’s Own soon after the  As much as the specific context of nascent fascism, this indirect approach to it through the internal ruminations of someone well-meaning but ultimately morally compromised, perhaps beyond redemption, seems timely to me. Stevens does not refuse Lord Darlington, for example, when instructed to dismiss two Jewish maids to preserve the “safety and well-being” of his guests. Against Miss Kenton’s passionate rebuke — “if you dismiss my girls tomorrow, it will be wrong, a sin as any sin ever was one” — he sets his own professional standards: “our professional duty is not to our own foibles and sentiments, but to the wishes of our employer.” It might seem a relatively modest act of bigotry to be complicit in, but it’s inexcusable nonetheless, intolerable both in itself (as Miss Kenton rightly notes) and as a concession to the creeping encroachment of worse horrors. Resistance may even mean the most on this personal scale, where you can act before events outsize and overtake you — but in any case the most anyone can do is refuse to cooperate with — or to normalize — what they know to be wrong. From inside Stevens’s head, we feel the appeal of compliance, of pretending that this one thing, or the next thing, doesn’t really matter very much. But against that dangerous ease, as we travel with him to a fuller understanding of what his political passivity has enabled, we can set our own rising horror — at the waste of his life, and at the possibility that

As much as the specific context of nascent fascism, this indirect approach to it through the internal ruminations of someone well-meaning but ultimately morally compromised, perhaps beyond redemption, seems timely to me. Stevens does not refuse Lord Darlington, for example, when instructed to dismiss two Jewish maids to preserve the “safety and well-being” of his guests. Against Miss Kenton’s passionate rebuke — “if you dismiss my girls tomorrow, it will be wrong, a sin as any sin ever was one” — he sets his own professional standards: “our professional duty is not to our own foibles and sentiments, but to the wishes of our employer.” It might seem a relatively modest act of bigotry to be complicit in, but it’s inexcusable nonetheless, intolerable both in itself (as Miss Kenton rightly notes) and as a concession to the creeping encroachment of worse horrors. Resistance may even mean the most on this personal scale, where you can act before events outsize and overtake you — but in any case the most anyone can do is refuse to cooperate with — or to normalize — what they know to be wrong. From inside Stevens’s head, we feel the appeal of compliance, of pretending that this one thing, or the next thing, doesn’t really matter very much. But against that dangerous ease, as we travel with him to a fuller understanding of what his political passivity has enabled, we can set our own rising horror — at the waste of his life, and at the possibility that  After well over a year, my application for promotion to Professor finally concluded last week, with the disappointing news that my appeal of President Florizone’s negative decision was unsuccessful.*

After well over a year, my application for promotion to Professor finally concluded last week, with the disappointing news that my appeal of President Florizone’s negative decision was unsuccessful.* It is tempting, of course, to use this opportunity to lay out my whole case, to rehearse the ups and downs as my application went through its nine (nine!) stages of review, and to air my specific grievances as well as parade my allies and advocates. Militating against that self-indulgent impulse, though, is the conviction that even if it were professionally appropriate to expose all the parties involved in that way, nobody really wants to read that 10,000 word screed. Besides, I’ve done a lot of relitigating of details in the past 16 months. It will do me more good to pull back a bit, to get out of the weeds and try instead to articulate what seems to have been the fundamental problem, which I now think can be aptly summed up as (to borrow a phrase from Middlemarch) “a total missing of each other’s mental track.” I won’t name names or quote at length from any submissions, and I’ll try to avoid special pleading — though I can hardly be expected to hide which side I’m on! It will help me to write about it in this way, I hope: it will exorcise some of the frustration and bitterness I still feel. And then I will be done with it — publicly, at least — and I will do my best to gather up all the energy that has been dispersed among these professional and psychological hindrances for so long and rededicate it to the ongoing task of becoming the kind of literary critic and

It is tempting, of course, to use this opportunity to lay out my whole case, to rehearse the ups and downs as my application went through its nine (nine!) stages of review, and to air my specific grievances as well as parade my allies and advocates. Militating against that self-indulgent impulse, though, is the conviction that even if it were professionally appropriate to expose all the parties involved in that way, nobody really wants to read that 10,000 word screed. Besides, I’ve done a lot of relitigating of details in the past 16 months. It will do me more good to pull back a bit, to get out of the weeds and try instead to articulate what seems to have been the fundamental problem, which I now think can be aptly summed up as (to borrow a phrase from Middlemarch) “a total missing of each other’s mental track.” I won’t name names or quote at length from any submissions, and I’ll try to avoid special pleading — though I can hardly be expected to hide which side I’m on! It will help me to write about it in this way, I hope: it will exorcise some of the frustration and bitterness I still feel. And then I will be done with it — publicly, at least — and I will do my best to gather up all the energy that has been dispersed among these professional and psychological hindrances for so long and rededicate it to the ongoing task of becoming the kind of literary critic and