Something might seem missing by the novel’s end, and that’s a clear sense of what larger narrative Obreht offers us about the genre she is at once using and revising. What story is Inland ultimately telling us about the American West, or about the tropes and limitations of the Western?

Something might seem missing by the novel’s end, and that’s a clear sense of what larger narrative Obreht offers us about the genre she is at once using and revising. What story is Inland ultimately telling us about the American West, or about the tropes and limitations of the Western?

“Camel. Camel. How could anyone have guessed?” thinks Nora Lark, one of the two main characters in Téa Obreht’s Inland. I certainly couldn’t, at first: there’s nothing in the way Lurie, the novel’s other protagonist, speaks to his companion Burke that gives it away; there’s nothing in the conventions of the genre to which Inland more or less belongs, the Western, that prepares us for it. Inland has another surprise for us too, something about Lurie himself that we learn only after his story and Nora’s have finally intersected. In both cases, shock quickly gives way to understanding, and to appreciation of Obreht’s ingenuity. While Inland includes many elements of the classic Western—there are outlaws and sheriffs, heists and hangings, settlers and “Indians”—Obreht persistently subverts our expectations of the stories to be told about them. The result is a panoramic saga at once familiar and strange.

The action of Inland unfolds through two contrasting storylines. In both of them, as in her widely-praised debut novel The Tiger’s Wife, Obreht pushes the boundaries of realism: in her worlds, the lines between fact and fancy, and between the living and the dead, are wavery ones. Lurie’s first-person narrative recounts his misadventures on the rough edges of nineteenth-century American society. His immigrant father Hadziosman Djurić was “mistaken for a Turk so often” he disowned both his name (becoming “Hodgeman Drury” and then “Hodge Lurie”) and his faith. Orphaned as a small boy, Lurie ends up working with a man known as the Coachman, who trades in corpses—some stolen fresh from the graveyard. It is while doing this grim work that Lurie first experiences a “strange feeling at the edges of myself”: from his contact with the dead he takes away a “whorling hunger” to satisfy their unfulfilled desires. “It’s not as cold as you would expect, the touch of the dead,” he later reflects:

The skin prickles like a dreaming limb. It’s not the strangeness of the feeling that terrifies you—it’s their want. It blows you open.

When Lurie and the Coachman are caught, Lurie is sentenced to work as a “hireling” alongside brothers Hobb and Donovan Mattie. When Hobb dies of typhoid, he passes on his “itch for pickpocketing” and Lurie and Donovan turn outlaw, robbing stagecoaches, waystations, and pack trains. One night during a heist Lurie seizes “an overbold New York kid” and beats him to death, and this begins the cat and mouse game between Lurie and Marshal John Berger, who becomes his dogged antagonist.

Hobb’s “want” is also what leads Lurie to Burke. One day in the spring of 1856, while heading down the Texas coast to elude Berger’s pursuit, he climbs aboard a ship docked at Indianola. Scouring the ship trying to appease Hobb’s craving, Lurie comes upon “a crude barn” erected near the stern. There he makes a discovery that changes his life forever:

And there of course—sightless, blundering into a fog of stink and breath, terrified suddenly beyond reason—what should I find but you?

The ship is the U.S.S. Supply and Lurie has chanced upon the Camel Corps, a real but little known military venture overseen by “a brooding, handsome, steadfast Syrian Turk” named Hadji Ali but called—through the same distorting process that rechristened Lurie’s father—Hi Jolly, Jolly for short. Jolly’s charges—“roaring, jostling, belching incredibly, dust-rolling, butting necks along wild laterals”—have been brought thousands of miles to “serve as pack animals for the cavalry” in territory where their legendary ability to cross long distances without water will make them invaluable.

At first just an enthralled observer, Lurie eventually becomes a full-time member of the cameleering troop. He finds himself at home among the men: for once, looking like a “Levantine” lets him blend in rather than stand out. And the camels, with their “profound intolerance and incredible strength,” win his unstinting admiration. “Camels are not for the faint of heart,” he tells us:

They are faster than one might expect, and twice as rattletrap. They are frowzy and irate. Their fur sloughs off and drifts, filling the air with a sweet, malty stench that frenzies mules and horses, who scatter to outrun their own terror.

“Their hearts belong to their riders,” he adds, and thus is born the powerful bond between Lurie and Burke that holds both them and the two strands of Inland together.

Lurie and Burke travel widely, first carrying out military missions with the Camel Corps and then, when Marshal Berger’s proximity once again puts Lurie on the run, serving in timber camps and on mining expeditions. In an elegiac mood, Lurie reminds Burke of the wonders they have seen:

You have stood on the shores of the mighty Platte, where Red Cloud’s Sioux, gathered for the parley that would be their ruin, had grazed a horseherd two thousand strong, balding the prairie all the way back to the tree line. You have seen the hunchback yuccas pick up their spiny skirts to flee an oncoming duststorm. … You have stood on bluffs planted up with scorched saplings where the ground was pocked with exhalations, with ruts belching white gobs of mud. You have walked the rim of a jaundiced gulch, veined high and low with bands of ore, through which the whitecaps of a nameless river went roaring.

Everywhere they go, the camels arouse wonder, fascination, and fear. “We saw curiously few Indians,” Lurie recalls; “word had got around, as it always did, that we were traveling with monsters.”

In contrast to Lurie’s wide-ranging tale, Nora’s story takes us through just a single eventful day in 1893 on and around her homestead in the Arizona Territory. She lives there with her husband Emmett, once a teacher, now a newspaper man; with her three sons Rob, Dolan, and Toby; with Emmett’s mother Harriet, “immobilized two years ago by a stroke”; and with Josie, “the daughter of Emmett’s cousin Martha,” who unlike Nora has yet to “harden” to their arduous frontier life. It’s not just that Josie is too soft for the work—”ordinary ranch implements confounded her”—but that she is awash in useless and often debilitating beliefs:

Churning around in Josie’s mind was an almanac of tincture remedies, Oriental magic, occult notions, absurd natural histories—especially those detailing the monstrous lizards unearthed by Cope and Marsh—all of which she talked ceaselessly about.

Above all, Josie is plagued by the dead, who, “according to Josie, were everywhere”: “They announced themselves to her in town; on the road; at church. Their sentiments were revealed to her abruptly and ferociously.”

Nora scorns Josie’s “unwelcome eccentricity,” which distracts Josie from the more literal threats that preoccupy Nora, such as, on this key day, their dwindling water supply. But Nora herself has a hidden relationship that also defies reason: she carries on constant silent conversations with the ghost of her baby daughter Evelyn. Evelyn’s death is part of what has transformed Nora from a hopeful, loving woman into a “tough, opinionated, rangy, sweating mule of a thing”: not just the tragedy itself, but Nora’s own role in it, which is one of the threads Obreht unspools for us as this difficult day drags on. It’s a day driven by thirst—for water, but also for information. Emmett has been missing for three days, and now Rob and Dolan too are not to be found. Meanwhile, Josie and sensitive young Toby are overwrought from fear of “the beast” Josie insists she has seen—“a ruffle-boned skeleton with great, folded wings on its back.” “You think I’m telling tales,” Toby complains when Nora is unconvinced by the signs he shows her of its menacing presence. “Mama don’t think the tracks are cloven,” he reports petulantly to Josie when they come back in from their investigation; “They don’t strike her as tracks at all.”

Thanks to Lurie’s tale, readers will guess the beast’s identity well before Nora does. Before that moment of revelation, however, much has yet to transpire, as Nora’s question for her missing husband and sons brings back memories and leads to encounters with her neighbors, the sheriff, and local ‘Cattle King’ Merrion Crace, all of whom are entangled in a controversy over a proposal to move the county seat from Amargo, where Nora and Emmett have settled, to nearby Ash River. Crace wants to shut down the opposition to the move for which Emmett’s paper has provided a forum; his leverage includes what he knows about Evelyn’s death and what he and the Sheriff tell Nora about Emmett’s fate, and about what Rob and Dolan have been up to since they rode off in the night.

Thanks to Lurie’s tale, readers will guess the beast’s identity well before Nora does. Before that moment of revelation, however, much has yet to transpire, as Nora’s question for her missing husband and sons brings back memories and leads to encounters with her neighbors, the sheriff, and local ‘Cattle King’ Merrion Crace, all of whom are entangled in a controversy over a proposal to move the county seat from Amargo, where Nora and Emmett have settled, to nearby Ash River. Crace wants to shut down the opposition to the move for which Emmett’s paper has provided a forum; his leverage includes what he knows about Evelyn’s death and what he and the Sheriff tell Nora about Emmett’s fate, and about what Rob and Dolan have been up to since they rode off in the night.

While Lurie is a man in constant motion, Nora is a woman seeking to stay put. After their marriage, the Larks had “followed railroad and rumor” for two years trying to establish a life for themselves on the frontier: “No sooner had Nora warmed to the curtains and mattresses of whatever place boarded them than they were off again.” Finally, in Amargo, bit by painful bit they build a home and a life for themselves and their growing family. “Should the county seat be lost to Ash River,” Nora knows, “all this would have been for nothing.” The pressure of change is inexorable, though, even in remote Amargo:

Hardly a day went by, it seemed, without the newspapers touting some remarkable discovery that had altered the truth or convenience of living … From Atlantic state palaces of learning, educational revues were making their way slowly inland to share the latest scientific advancements: anatomical marvels and wonders of automation. Put together, these all had the effect of drawing things closer to one another, of illuminating that grainy twilight beyond which lay the landscape of a new and truer world.

Emmett (if he ever returned) would, she knows, have no qualms about moving on yet again: “All difficulties in Emmett’s view could be solved by pulling up stakes.” But all Nora can think about is what they might leave behind with this house where “every beam, every mirror, every corner … breathed with the immutable spirit of her daughter. “If I leave here,” she says plaintively to the Evelyn only she can perceive, “will you come with me? Or will you have to stay?”

The strength of the bond between the living and the dead shapes both Lurie’s and Nora’s stories. The novel’s many ghosts might seem to push Inland out of history towards fantasy. As Nora eventually concludes, however, truth is already proving stranger than fiction:

If electromagnetic pulses could fly through the air; if giants with shinbones the length of her entire body had once roamed ancient seas; if the world was plagued by living creatures so miniscule that no living eye could see them, but so vicious that they could lay waste to entire cities—was it not also possible that Josie’s claims … might hold some truth? Might the dead truly inhabit the world alongside the living: laughing, thriving, growing and occupying themselves with the myriad mundanities of afterlife, invisible merely because the mechanism of seeing them had yet to be invented?

Lurie’s story in particular, it turns out, depends on answering “yes” to these rhetorical questions, but Inland as a whole plays with their implications, building a world on “what if” premises that, as Nora’s equivocal skepticism shows, are sometimes easier to dismiss in theory than in practice. More even than Obreht’s nineteenth-century characters, after all, we have learned to live with belief in what we cannot see.

Obreht vividly evokes the sights, sounds, and moods of her frontier setting: Inland conveys both what it is like to travel, fight, and forage across the miles with Lurie and Burke and how it feels to scrabble and fret with Nora and her family on the precarious margins of the modernizing world. For all the pleasures of Obreht’s prose and the originality of her intertwined plots, though, something might seem missing by the novel’s end, and that’s a clear sense of what larger narrative Obreht offers us about the genre she is at once using and revising. What story is Inland ultimately telling us about the American West, or about the tropes and limitations of the Western? Hers is certainly an unconventionally populated saga: both camels and Muslims, though present in reality, are missing in nation-building myth. Inland reminds us that if they seem alien in the landscape she draws it is only because we have not seen it clearly before. The underlying logic of the frontier, however, with its commitment to settler colonialism, is never challenged. While clinging to her home in Amargo, Nora never questions her right to the land; to her, its original inhabitants are the aliens, their proximity filling her with “a plunging dread.”

Yet in the shadows of Nora’s anxious racism, which turns out to have had devastating consequences, we can perhaps glimpse the critique Obreht refrains from spelling out explicitly. One hot day, carrying Evelyn on her front, Nora sees “a dark rider on a spotted horse” on the horizon: “she thought Apache because the word had been growing in her like an illness all her life.” Panicked, she hides in the field for hours, with Evelyn pressed between her body and the ground. It is this act of fear and suspicion that brings on the heatstroke that leads to Evelyn’s death. “There were Indians,” Nora insists ever after; “Five of them. Apaches.” But it wasn’t Indians: it was her neighbor Armando Cortez—“a dark man,” yes, but no more a threat than the Navajo woman (or is she Apache? Nora, revealingly, cannot tell) whose inscrutable visits have exacerbated Nora’s self-destructive paranoia.

Lurie and Nora, then, are linked not just by Burke or by ghosts but also by white Americans’ pervasive fear of “dark” others, though Lurie is a victim of this bias while Nora is one of its perpetrators. Lurie finds unlikely fellowship among the cameleers, his kinship with them symbolized in the glass bead he steals from the ship where he also finds Burke—“deepwater blue, painted up with a dizziness of receding circles … something very like the nazar my father had kept in his pocket.” Much later, the nazar turns up in Nora’s barn, a tangible reminder of the interconnectedness of even the most apparently dissimilar lives. While for Lurie strangeness becomes his freedom, even his happiness, Nora’s fear of it has hemmed her in. By the end of the novel she can at least picture something different, a life more fluid and various. Obreht, in her turn, makes the Western strange to her readers, offering us an account not of how the West was won but of how its real diversity could be reimagined.

There’s an almost stately simplicity to the novel’s unfolding after this precipitating crisis, which launches its characters into a strange state of limbo. Lucy’s parents, unaware of developments back in Lahardane, roam Europe, exiled from home and happiness by their grief and guilt; Lucy, shamed by what she has done, pays penance for it with a life of near total isolation, even refusing love, when it is offered, as something she cannot accept “until she felt forgiven.” When a reunion finally comes, it is almost too late to repair the damage they have collectively wrought or to make up for the time spent apart, mourning and waiting. There is redemption in the story, though, and it comes from what the nuns who visit Lucy late in her life call her “gift of mercy.” Lucy herself sees nothing extraordinary in what she has done, nothing that needs the kind of explanation others wish they could command: “for what does it matter, really, why people visit one another or walk behind a coffin, only that they do?”

There’s an almost stately simplicity to the novel’s unfolding after this precipitating crisis, which launches its characters into a strange state of limbo. Lucy’s parents, unaware of developments back in Lahardane, roam Europe, exiled from home and happiness by their grief and guilt; Lucy, shamed by what she has done, pays penance for it with a life of near total isolation, even refusing love, when it is offered, as something she cannot accept “until she felt forgiven.” When a reunion finally comes, it is almost too late to repair the damage they have collectively wrought or to make up for the time spent apart, mourning and waiting. There is redemption in the story, though, and it comes from what the nuns who visit Lucy late in her life call her “gift of mercy.” Lucy herself sees nothing extraordinary in what she has done, nothing that needs the kind of explanation others wish they could command: “for what does it matter, really, why people visit one another or walk behind a coffin, only that they do?” Is the story of Lucy Gault a tragic one? I don’t think so. It is a sad one, certainly, but for all its heartbreak the novel conveys the same sense of peace that draws the visiting nuns to Lucy’s home:

Is the story of Lucy Gault a tragic one? I don’t think so. It is a sad one, certainly, but for all its heartbreak the novel conveys the same sense of peace that draws the visiting nuns to Lucy’s home: “We had a limit known as the Whipple line, below which we would not sink. Dorothy Whipple was a popular novelist of the 1930s and 1940s whose prose and content absolutely defeated us. A considerable body of women novelists, who wrote like the very devil, bit the Virago dust when Alexandra, Lynn and I exchanged books and reports, on which I would scrawl a brief rejection: ‘Below the Whipple line.'” —

“We had a limit known as the Whipple line, below which we would not sink. Dorothy Whipple was a popular novelist of the 1930s and 1940s whose prose and content absolutely defeated us. A considerable body of women novelists, who wrote like the very devil, bit the Virago dust when Alexandra, Lynn and I exchanged books and reports, on which I would scrawl a brief rejection: ‘Below the Whipple line.'” —

But. It really doesn’t do more than tell this story. There aren’t any layers to it. The characters are fairly two dimensional, especially the French temptress Louise, who to me was the novel’s weakest element. She’s a selfish narcissist who takes what she wants for her own gratification. The whole catastrophe, in fact, is the result of her resentment at an old lover in her home town in France, himself blithely ignorant “that he, at such a distance, could have had anything to do with the breaking up of that family” or with the rift that opens up between Louise and her own parents. Her unmitigated nastiness sapped the novel of any chance of a real moral or emotional dilemma at its center: Avery is wrong to get involved with her and that’s that. Whipple plays out the moves on the board she has set up, but there’s nothing in it for us to think about: we just follow it all through to the end. And that is just not a terribly interesting exercise: Ellen is a bit of a limp noodle, and the solution that unfolds to her problem of finding her own place in the world is too pat, too easy.

But. It really doesn’t do more than tell this story. There aren’t any layers to it. The characters are fairly two dimensional, especially the French temptress Louise, who to me was the novel’s weakest element. She’s a selfish narcissist who takes what she wants for her own gratification. The whole catastrophe, in fact, is the result of her resentment at an old lover in her home town in France, himself blithely ignorant “that he, at such a distance, could have had anything to do with the breaking up of that family” or with the rift that opens up between Louise and her own parents. Her unmitigated nastiness sapped the novel of any chance of a real moral or emotional dilemma at its center: Avery is wrong to get involved with her and that’s that. Whipple plays out the moves on the board she has set up, but there’s nothing in it for us to think about: we just follow it all through to the end. And that is just not a terribly interesting exercise: Ellen is a bit of a limp noodle, and the solution that unfolds to her problem of finding her own place in the world is too pat, too easy. I did enjoy Someone At A Distance in the moment, but I also found myself comparing it unfavorably to another much better book (in my opinion) about an affair, Joanna Trollope’s Marrying the Mistress. In Trollope’s novel the “mistress” is a genuinely sympathetic character; the relationship that develops creates a genuine tension for the husband and then, eventually, for his children, who can’t help but like his new partner in spite of their loyalty to their mother; and the marriage that ends, while not a bad one, has weak spots that made it vulnerable—indeed, that maybe even made its end, while painful, a change worth bringing about. Yet even though her mistress is not an evil temptress, Trollope is less sentimental about love, and less blandly optimistic about fixing what has been broken. Someone At A Distance ends with the promise of restoration, but why? Knowing what she now knows about her husband, what is that promise worth to Ellen? I didn’t really care, though: by that point I was ready to be finished with her.

I did enjoy Someone At A Distance in the moment, but I also found myself comparing it unfavorably to another much better book (in my opinion) about an affair, Joanna Trollope’s Marrying the Mistress. In Trollope’s novel the “mistress” is a genuinely sympathetic character; the relationship that develops creates a genuine tension for the husband and then, eventually, for his children, who can’t help but like his new partner in spite of their loyalty to their mother; and the marriage that ends, while not a bad one, has weak spots that made it vulnerable—indeed, that maybe even made its end, while painful, a change worth bringing about. Yet even though her mistress is not an evil temptress, Trollope is less sentimental about love, and less blandly optimistic about fixing what has been broken. Someone At A Distance ends with the promise of restoration, but why? Knowing what she now knows about her husband, what is that promise worth to Ellen? I didn’t really care, though: by that point I was ready to be finished with her. We all have our crosses to bear, our own personal sorrows. Mine is that the people who should be dearest to me, my own children, my sisters, consider me a bad woman. The grandchildren have been taught to be wary. I think I’m a disgrace to them, really. After the war when the newsreel film was shown of what had gone on in Germany and Poland, those places, the horrors . . . It all got tangled up in their minds, as if we’d stood for such barbarism.

We all have our crosses to bear, our own personal sorrows. Mine is that the people who should be dearest to me, my own children, my sisters, consider me a bad woman. The grandchildren have been taught to be wary. I think I’m a disgrace to them, really. After the war when the newsreel film was shown of what had gone on in Germany and Poland, those places, the horrors . . . It all got tangled up in their minds, as if we’d stood for such barbarism. Even after her long imprisonment Phyllis remains indignant that her commitment to Mosley’s cause has cost her anything at all and especially that it has led to people concluding she is not a good person. It would be at once pathetic and laughable if it weren’t also plausible and unhappily timely: Phyllis insists that she and her fascist friends were very fine people. The novel approaches them with sly delicacy, never presenting them as outright villains but allowing the us to experience their moral corruption through the lens of Phyllis’s own self-justifications. It also focuses on the personal relationships that naturalize and sanitize the fascist cause for those directly involved, keeping the political context just vague enough that the reader almost has to shake herself to remember that what they stand for is not acceptable, that fascism isn’t just one reasonable choice among many no matter how elegantly its proponents are dressed or how preoccupied they are with their families, lovers, and friends.

Even after her long imprisonment Phyllis remains indignant that her commitment to Mosley’s cause has cost her anything at all and especially that it has led to people concluding she is not a good person. It would be at once pathetic and laughable if it weren’t also plausible and unhappily timely: Phyllis insists that she and her fascist friends were very fine people. The novel approaches them with sly delicacy, never presenting them as outright villains but allowing the us to experience their moral corruption through the lens of Phyllis’s own self-justifications. It also focuses on the personal relationships that naturalize and sanitize the fascist cause for those directly involved, keeping the political context just vague enough that the reader almost has to shake herself to remember that what they stand for is not acceptable, that fascism isn’t just one reasonable choice among many no matter how elegantly its proponents are dressed or how preoccupied they are with their families, lovers, and friends. My

My  I thought it might help to write for some places that do run longer pieces, so I wrote a review “on spec” for one such venue but they didn’t want it–in the end it maybe wasn’t a great fit with the place I sent it, although the book I chose (

I thought it might help to write for some places that do run longer pieces, so I wrote a review “on spec” for one such venue but they didn’t want it–in the end it maybe wasn’t a great fit with the place I sent it, although the book I chose ( This is why I keep returning to class prep! It’s so straightforward, and after all, it does have to get done. Maybe I should think of it this way: the better prepared I am for the term, the more likely it is that I can keep working on some kind of writing project even after classes start. My colleagues and I often talk about the way teaching expands to fill however much time you can (or are willing to) give it: this is something we advise TAs and junior colleagues to guard against. Good, detailed course planning is part of a strategy for achieving better balance between my various professional obligations; it’s not just a diversionary tactic when your other commitments are getting you down. Right? RIGHT?!

This is why I keep returning to class prep! It’s so straightforward, and after all, it does have to get done. Maybe I should think of it this way: the better prepared I am for the term, the more likely it is that I can keep working on some kind of writing project even after classes start. My colleagues and I often talk about the way teaching expands to fill however much time you can (or are willing to) give it: this is something we advise TAs and junior colleagues to guard against. Good, detailed course planning is part of a strategy for achieving better balance between my various professional obligations; it’s not just a diversionary tactic when your other commitments are getting you down. Right? RIGHT?!

Thanks to Lurie’s tale, readers will guess the beast’s identity well before Nora does. Before that moment of revelation, however, much has yet to transpire, as Nora’s question for her missing husband and sons brings back memories and leads to encounters with her neighbors, the sheriff, and local ‘Cattle King’ Merrion Crace, all of whom are entangled in a controversy over a proposal to move the county seat from Amargo, where Nora and Emmett have settled, to nearby Ash River. Crace wants to shut down the opposition to the move for which Emmett’s paper has provided a forum; his leverage includes what he knows about Evelyn’s death and what he and the Sheriff tell Nora about Emmett’s fate, and about what Rob and Dolan have been up to since they rode off in the night.

Thanks to Lurie’s tale, readers will guess the beast’s identity well before Nora does. Before that moment of revelation, however, much has yet to transpire, as Nora’s question for her missing husband and sons brings back memories and leads to encounters with her neighbors, the sheriff, and local ‘Cattle King’ Merrion Crace, all of whom are entangled in a controversy over a proposal to move the county seat from Amargo, where Nora and Emmett have settled, to nearby Ash River. Crace wants to shut down the opposition to the move for which Emmett’s paper has provided a forum; his leverage includes what he knows about Evelyn’s death and what he and the Sheriff tell Nora about Emmett’s fate, and about what Rob and Dolan have been up to since they rode off in the night.

I have read a handful of books recently that I haven’t written up properly here; I thought I would say at least a little bit about them before my impressions fade away.

I have read a handful of books recently that I haven’t written up properly here; I thought I would say at least a little bit about them before my impressions fade away.

At a block party recently I mentioned to a neighbor that I was curious about Michael Ondaatje’s Warlight, so she kindly lent me her copy. I read it with interest at first but found my attention flagging. It too, in its own way, is a very atmospheric novel, but there didn’t seem to be much more to the novel than atmosphere: not much happens, even in the retrospective spy story that sounds as if it should be suspenseful and, if not action packed, at least eventful. There are events, but they always seemed strangely at a distance; I found Ondaatje’s style portentous, always promising but deferring some deeper meaning that I didn’t think was ever actually delivered. I read The English Patient years ago and I remember liking it, but that was in the dark days Before Blogging, so I can’t go back to an old post to see what I liked about it. A bit of Twitter discussion suggests Ondaatje is a divisive writer. I can see why, given how self-conscious his style is. I liked a lot of moments. One near the end suggested to me the principle the novel itself may be built on:

At a block party recently I mentioned to a neighbor that I was curious about Michael Ondaatje’s Warlight, so she kindly lent me her copy. I read it with interest at first but found my attention flagging. It too, in its own way, is a very atmospheric novel, but there didn’t seem to be much more to the novel than atmosphere: not much happens, even in the retrospective spy story that sounds as if it should be suspenseful and, if not action packed, at least eventful. There are events, but they always seemed strangely at a distance; I found Ondaatje’s style portentous, always promising but deferring some deeper meaning that I didn’t think was ever actually delivered. I read The English Patient years ago and I remember liking it, but that was in the dark days Before Blogging, so I can’t go back to an old post to see what I liked about it. A bit of Twitter discussion suggests Ondaatje is a divisive writer. I can see why, given how self-conscious his style is. I liked a lot of moments. One near the end suggested to me the principle the novel itself may be built on: Finally, I just finished reading Joy Kogawa’s Obasan for my book club. This novel is, of course, a Canadian classic, and I think I must have read it before, though I did not have any specific memory of it. It is a very powerful novel, and a very artful one as well. It is also a depressingly timely one: so much of the racism and anger directed at Japanese Canadians, vilified and scapegoated in the 1940s, is echoed in current anti-immigrant rhetoric, especially but certainly not exclusively in the United States right now. “Which year should we choose for our healing?” Naomi asks, reading through her aunt’s archive of documents about “Canadians of Japanese origin who were expelled from British Columbia in 1941 and are still debarred from returning to their homes.” “Restrictions against us are removed on April Fool’s Day, 1949,” she notes,

Finally, I just finished reading Joy Kogawa’s Obasan for my book club. This novel is, of course, a Canadian classic, and I think I must have read it before, though I did not have any specific memory of it. It is a very powerful novel, and a very artful one as well. It is also a depressingly timely one: so much of the racism and anger directed at Japanese Canadians, vilified and scapegoated in the 1940s, is echoed in current anti-immigrant rhetoric, especially but certainly not exclusively in the United States right now. “Which year should we choose for our healing?” Naomi asks, reading through her aunt’s archive of documents about “Canadians of Japanese origin who were expelled from British Columbia in 1941 and are still debarred from returning to their homes.” “Restrictions against us are removed on April Fool’s Day, 1949,” she notes, Elizabeth Jenkins’s The Tortoise and the Hare is a small gem of a novel–not a sparkly diamond, but something a bit overcast and somber despite its polish, like a black pearl. It is a wry small-scale tragedy, or possibly, if you feel less sympathetic towards its main characters, a bleak domestic comedy. As fa as its plot goes, it is modest and almost painfully intimate: it tells the superficially simple story of a marriage coming apart. The explicit cause of its collapse is an affair, but as self-help books often suggest, adultery can be a symptom of a faltering relationship as much as an explanation for it, and that is certainly true for the characters in The Tortoise and the Hare.

Elizabeth Jenkins’s The Tortoise and the Hare is a small gem of a novel–not a sparkly diamond, but something a bit overcast and somber despite its polish, like a black pearl. It is a wry small-scale tragedy, or possibly, if you feel less sympathetic towards its main characters, a bleak domestic comedy. As fa as its plot goes, it is modest and almost painfully intimate: it tells the superficially simple story of a marriage coming apart. The explicit cause of its collapse is an affair, but as self-help books often suggest, adultery can be a symptom of a faltering relationship as much as an explanation for it, and that is certainly true for the characters in The Tortoise and the Hare. Imogen (as her name implies) has all the qualities of a conventional romantic heroine of the English rose variety, the kind of woman who should win the game. That’s certainly what she thinks, and her very expectation of success is, one of her friends eventually suggests, what defeats her:

Imogen (as her name implies) has all the qualities of a conventional romantic heroine of the English rose variety, the kind of woman who should win the game. That’s certainly what she thinks, and her very expectation of success is, one of her friends eventually suggests, what defeats her: The Tortoise and the Hare is not that book, though, any more than it is a wholly sympathetic picture of Imogen’s plaintive suffering. Still, all the affect of the novel–its emotional texture–is on Imogen’s side: I actually found it quite stressful being immersed in her anxious uncertainty as she watched Evelyn’s relationship with Blanche reach further and further into the corners of her own life, including her awkward relationship with her son Gavin (who is, in his turn, an unattractive reiteration of his father’s least sensitive aspects). Once the truth is impossible to deny or ignore, her indecision is painful but completely understandable. “You did use to have very liberal ideas about these matters,” Evelyn says when finally confronted. “But I did not ever imagine quite this sort of thing,” says Imogen: “so domestic, like a wife already.” She thought she could cope with “an ornament, an addition,” but instead she has found herself displaced, redundant, in the one role she knows how to fill.

The Tortoise and the Hare is not that book, though, any more than it is a wholly sympathetic picture of Imogen’s plaintive suffering. Still, all the affect of the novel–its emotional texture–is on Imogen’s side: I actually found it quite stressful being immersed in her anxious uncertainty as she watched Evelyn’s relationship with Blanche reach further and further into the corners of her own life, including her awkward relationship with her son Gavin (who is, in his turn, an unattractive reiteration of his father’s least sensitive aspects). Once the truth is impossible to deny or ignore, her indecision is painful but completely understandable. “You did use to have very liberal ideas about these matters,” Evelyn says when finally confronted. “But I did not ever imagine quite this sort of thing,” says Imogen: “so domestic, like a wife already.” She thought she could cope with “an ornament, an addition,” but instead she has found herself displaced, redundant, in the one role she knows how to fill. The

The

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

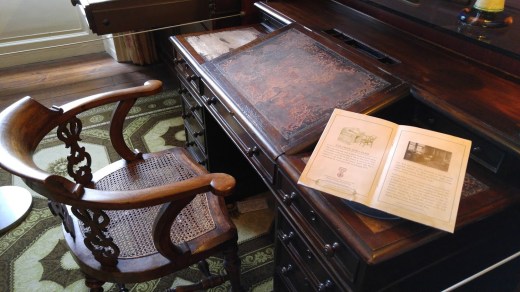

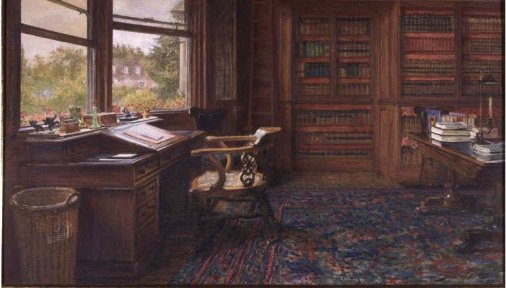

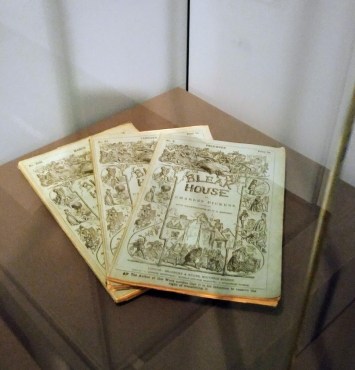

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon.

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon. Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

Although Ernest’s murder and the subsequent trial are the novel’s central plot points, however, or at least its most dramatic ones, it’s interesting how easily subsumed their effects are in the novel’s quieter undercurrents. Surely an act as significant as murder should turn the novel itself into melodrama, should in some way transform our perspective on its characters. How can a woman dubbed “the weedkiller killer” by the tabloids seem so harmless–seem almost, even more provocatively, like a victim herself? Ernest, though abhorrent, is surely not so evil that he deserves his fate, and Elsie and Rene are hardly heroic figures of resistance, to patriarchy or to anything else. Yet all they ever wanted was to live quietly and honestly, and together, and as the lawyers and journalists gather and gawk, Ernest starts to seem in retrospect like a graceless embodiment of all the social forces that try to make something strange and ugly out of their intimacy. The glare of publicity exposes them to all the prurience the novel itself scrupulously avoids:

Although Ernest’s murder and the subsequent trial are the novel’s central plot points, however, or at least its most dramatic ones, it’s interesting how easily subsumed their effects are in the novel’s quieter undercurrents. Surely an act as significant as murder should turn the novel itself into melodrama, should in some way transform our perspective on its characters. How can a woman dubbed “the weedkiller killer” by the tabloids seem so harmless–seem almost, even more provocatively, like a victim herself? Ernest, though abhorrent, is surely not so evil that he deserves his fate, and Elsie and Rene are hardly heroic figures of resistance, to patriarchy or to anything else. Yet all they ever wanted was to live quietly and honestly, and together, and as the lawyers and journalists gather and gawk, Ernest starts to seem in retrospect like a graceless embodiment of all the social forces that try to make something strange and ugly out of their intimacy. The glare of publicity exposes them to all the prurience the novel itself scrupulously avoids: In retrospect, I’m glad my pitch for a article reporting back on the George Eliot Bicentenary Conference was rejected: the cognitive dissonance I struggled with during the conference was strong enough that I have been puzzling over how or whether to write about it even here, in relative obscurity and without being answerable to anyone else for whatever it is that I come up with to say.

In retrospect, I’m glad my pitch for a article reporting back on the George Eliot Bicentenary Conference was rejected: the cognitive dissonance I struggled with during the conference was strong enough that I have been puzzling over how or whether to write about it even here, in relative obscurity and without being answerable to anyone else for whatever it is that I come up with to say.

Each of the presenters on our panel addressed quite a different “application” for George Eliot. I spoke about what I see as reasons for but also the difficulties with “pitching” her work to the kind of bookish public I have been trying to write for–at left is my design for a George Eliot tote bag meant to illustrate the case I made that her books are not, as too often assumed,

Each of the presenters on our panel addressed quite a different “application” for George Eliot. I spoke about what I see as reasons for but also the difficulties with “pitching” her work to the kind of bookish public I have been trying to write for–at left is my design for a George Eliot tote bag meant to illustrate the case I made that her books are not, as too often assumed,

It isn’t exactly that I want no part of it, though. As I hope I have also made clear here over the years, my own intellectual life has been shaped and enriched by many kinds of academic scholarship (though

It isn’t exactly that I want no part of it, though. As I hope I have also made clear here over the years, my own intellectual life has been shaped and enriched by many kinds of academic scholarship (though