Billie puts her mug of coffee down too, then goes round to place the vase on the windowsill. The flowers seem almost to glow in the spring light. All these little things, these kindnesses that Billie does for her: it’s an odd reversal, being looked after like this. Madeline catches the scent of ginger and lemon, and the flowers’ sharp musk, and beneath that the warm oiliness of her daughter’s coffee, and then under it all the rank whiff of wool from the rug over her knees, and it makes her stomach churn. She swallows, raises her face to the breeze from the window. She feels a wash of love and gratitude, and after it an undertow of grief. Deep in her flesh, she knows what’s coming. What she’s going to put Billie through.

The Undertow is the kind of book that can sound like—and often is—a soggy cliché: a multigenerational saga, the story of a family across a turbulent century that sees three of its sons go off to war and all of its mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, pass through dramatic changes of morals, mores, and fashions … you know the type! And it is exactly that kind of novel structurally; it’s just that Baker is a good enough writer to use this conventional framework in a fresh and often moving way. In fact, The Undertow may be my favorite Jo Baker novel so far.

The Undertow follows four generations of the Hastings family: William, his son Billy, his son Will, and his daughter Billie. “The lot of you,” Billie says, “like a set of Russian dolls … Chips off the old block, the lot of you.” Then, seeing that she has made her father Will uneasy, she qualifies her observation: “Same block, maybe, different chips.” Will’s discomfort reflects his fraught relationship with Billy, whose harsh moodiness (though Will does not know this) reflects his difficulty accepting what, in his mind, was the price he paid for the life Will would go on to lead: his killing of a young German sniper during the D-Day invasion. It’s an episode told without flamboyance—Baker’s style here, as in the other novels of hers that I’ve read, is concrete and descriptive, not minimalist but powerfully concise:

The day is muffled; there’s a high-pitched hum in Billy’s ears. Nothing happens. The body slips a little further over to one side. Grass, and headstones, and the blistered paint on the railings Nothing happens. The bird starts to sing again … Billy comes up to the foot of the grave and looks the body over. He can’t see where he hit him. He reaches round the kerbed edge of the grave, and crouches down, and reaches out and takes hold of the jaw to turn the face towards him. The skin is particularly smooth. It is still warm. It is a child. His greenish eyes are vague and dead.

Contemplating Will, born (as Billy sees it) imperfect, with Perthes disease—which will pain Will throughout his life—Billy thinks,

Contemplating Will, born (as Billy sees it) imperfect, with Perthes disease—which will pain Will throughout his life—Billy thinks,

The boy will turn out fine, better than fine. Billy insists on it. Anything less than this is unacceptable. This is his second chance. He’s paid for it. That boy’s death in Normandy was the down payment. The drip drip drip of guilt, that’s just the interest.

Billy’s unexpressed shame, rage, and grief drag are a weight that he is never really able to overcome. It’s hard for us to judge Billy too harshly, though, as his own father died at Gallipoli before Billy was even born, leaving his young wife to grieve and Billy ever-conscious of the absence, the emotional abyss, in their lives. We also know about the dreams Billy had and gave up, of a kind of glory that had nothing to do with war. Will in his turn is both suffering and deeply flawed; when his daughter Billie runs away to her beloved grandparents (Billy better able to show her the tenderness he couldn’t extend to Will), it’s easy to understand why she wants to get away but also, as she eventually discovers, to believe that it is possible and necessary to forgive.

I liked the ebb and flow in our sympathies across the novel: Baker creates people who seem genuinely complicated. She’s also clever about how she presents their stories, overlapping them as we move through the generations so that the protagonists of one phase take up new roles in the next, their children claiming centrality and then yielding it in their turn. Across the novel this becomes part of the larger story: the pathos of aging, the inevitable shift and change of the passing years. The boy who learned to ride a bike to make deliveries becomes the young man who wins races, then the soldier who rides into occupied France; then he’s a father and finally a grandfather, his bicycle hung up then given away as his son grows up and then grows old—meanwhile his daughter moves into position. We all take our turns at life, the novel reminds us; only to ourselves are we ever or always the main character.

Baker deftly creates unity across her storylines beyond the family relationships. The postcards William sends back from the front in WWI, for instance, cherished by his wife, are saved through the years and finally examined with care by Billie, remnants of a lost love and a vanished life that tell her that “even in the depths of war” he had found beauty as well as suffering in the world. She’s right, we know, because we were with William in 1915. We were with him when he saw Caravaggio’s The Beheading of St. John the Baptist in Malta, before his ship continued on to Gallipoli—and then we see it again in Malta with Billie when she takes up an artist’s residency on the island, neatly closing the loop. The painting makes both William and Billie reflect on the violence they know or fear in their world, as well as the paradox that great horrors can make great art. I think that’s something Baker is experimenting with too: her novel emphasizes both the literal devastation of war and terrorism and their less tangible but equally lasting legacies. This sense of pain and beauty coexisting is, I think, one facet of the “undertow” of the title. On a more domestic level, the tug downward comes from the ever-present knowledge that death is “what’s coming,” that our turns come and then are over. The epigraph from Ecclesiastes draws these things together: “One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh. All the rivers run to the sea and yet the sea is not full.” Overall, then, it’s a melancholy book, though there are certainly moments of uplift which, by and large, come from the little things in life:

Baker deftly creates unity across her storylines beyond the family relationships. The postcards William sends back from the front in WWI, for instance, cherished by his wife, are saved through the years and finally examined with care by Billie, remnants of a lost love and a vanished life that tell her that “even in the depths of war” he had found beauty as well as suffering in the world. She’s right, we know, because we were with William in 1915. We were with him when he saw Caravaggio’s The Beheading of St. John the Baptist in Malta, before his ship continued on to Gallipoli—and then we see it again in Malta with Billie when she takes up an artist’s residency on the island, neatly closing the loop. The painting makes both William and Billie reflect on the violence they know or fear in their world, as well as the paradox that great horrors can make great art. I think that’s something Baker is experimenting with too: her novel emphasizes both the literal devastation of war and terrorism and their less tangible but equally lasting legacies. This sense of pain and beauty coexisting is, I think, one facet of the “undertow” of the title. On a more domestic level, the tug downward comes from the ever-present knowledge that death is “what’s coming,” that our turns come and then are over. The epigraph from Ecclesiastes draws these things together: “One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh. All the rivers run to the sea and yet the sea is not full.” Overall, then, it’s a melancholy book, though there are certainly moments of uplift which, by and large, come from the little things in life:

But for now, the blackbird still sings outside the window. Now there is just the kiss, and the taste of coffee, and the clear strong knowledge that this, however brief, is happiness.

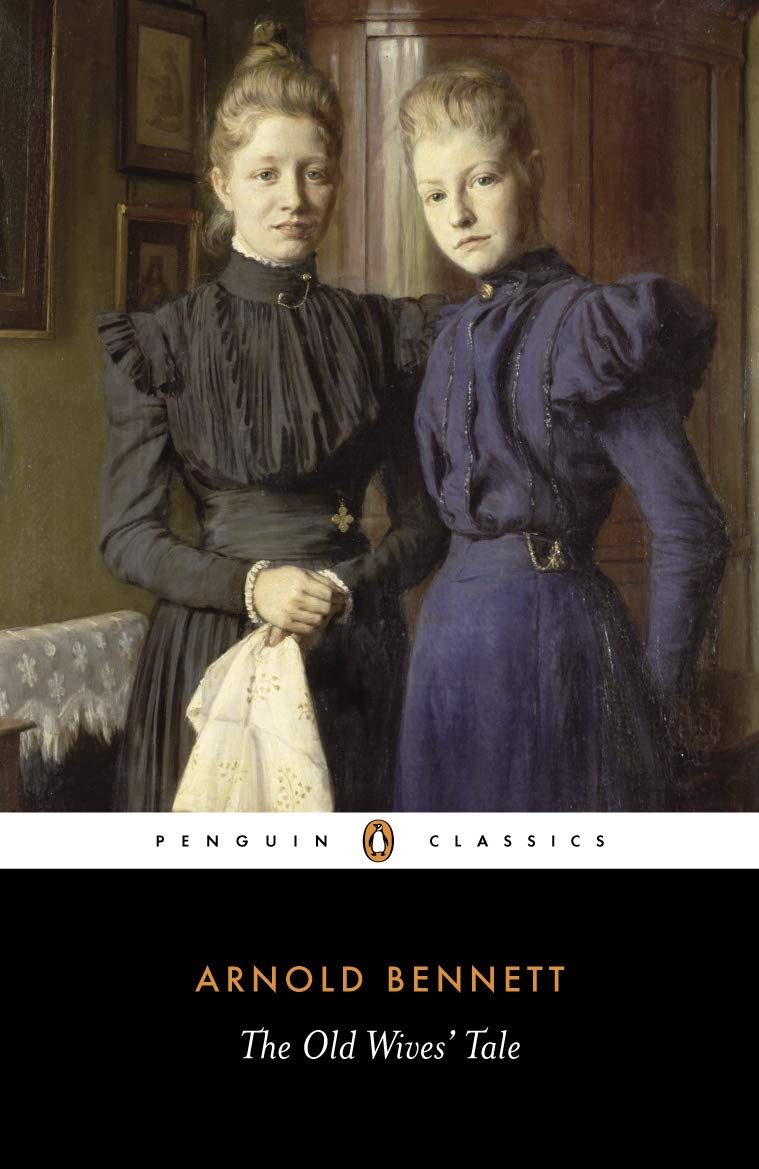

You cannot drink tea out of a teacup without the aid of the Five Towns; … you cannot eat a meal in decency without the aid of the Five Towns … All the everyday crockery used in the kingdom is made in the Five Towns—all, and much besides.

You cannot drink tea out of a teacup without the aid of the Five Towns; … you cannot eat a meal in decency without the aid of the Five Towns … All the everyday crockery used in the kingdom is made in the Five Towns—all, and much besides. Exhibit A here, for me, is the tooth pulling. The whole story of Mr. Povey’s toothache and his (highly relatable!) anxiety about going to the dentist is brilliant. “He seemed to be trying ineffectually to flee from his tooth as a murderer tries to flee from his conscience”: that’s a great line, capturing both the man and the mood perfectly. I loved Constance and Sophia’s trepidation as they prepare the laudanum (“Constance took the bottle as she might have taken a loaded revolver … Must this fearsome stuff, whose very name was a name of fear, be introduced in spite of printed warnings into Mr. Povey’s mouth? The responsibility was terrifying”)—and then the rise in both their courage and their impudence as they feel their power over their “patient.” But I did not expect the climax of this scene to be Sophia going at the unconscious Mr. Povey with a pair of pliers (“This was the crown of Sophia’s career as a perpetrator of the unutterable”); I didn’t anticipate her getting the wrong tooth after all, or her wanting to keep the tooth (eww?)—or its becoming the occasion for a terrible breach between the sisters, when Constance violates the sacrosanct privacy of Sophia’s work-box to seize “the fragment of Mr. Povey” and throw it out the window. The whole sequence is hilarious and graphic (that long description of the loose tooth in “the singular landscape” of Mr. Povey’s open mouth!) and, well,

Exhibit A here, for me, is the tooth pulling. The whole story of Mr. Povey’s toothache and his (highly relatable!) anxiety about going to the dentist is brilliant. “He seemed to be trying ineffectually to flee from his tooth as a murderer tries to flee from his conscience”: that’s a great line, capturing both the man and the mood perfectly. I loved Constance and Sophia’s trepidation as they prepare the laudanum (“Constance took the bottle as she might have taken a loaded revolver … Must this fearsome stuff, whose very name was a name of fear, be introduced in spite of printed warnings into Mr. Povey’s mouth? The responsibility was terrifying”)—and then the rise in both their courage and their impudence as they feel their power over their “patient.” But I did not expect the climax of this scene to be Sophia going at the unconscious Mr. Povey with a pair of pliers (“This was the crown of Sophia’s career as a perpetrator of the unutterable”); I didn’t anticipate her getting the wrong tooth after all, or her wanting to keep the tooth (eww?)—or its becoming the occasion for a terrible breach between the sisters, when Constance violates the sacrosanct privacy of Sophia’s work-box to seize “the fragment of Mr. Povey” and throw it out the window. The whole sequence is hilarious and graphic (that long description of the loose tooth in “the singular landscape” of Mr. Povey’s open mouth!) and, well,  I suppose its main function is to help establish the characters of the two sisters, who certainly reveal themselves as they squabble over the tooth: “the beauty of Sophia, the angelic tenderness of Constance, and the youthful, naïve, innocent charm of both of them, were transformed into something sinister and cruel.” A lot of these four first chapters is about setting up the contrast between them, which I know becomes a major structuring principle of the novel as it goes on. Chapter 4 makes this point really clearly, as it looks at how they have “grown up”: “The sisters were sharply differentiated,” the narrator remarks, in case we couldn’t tell. Constance’s name anticipates her more homely path, while Sophia’s hints at her “yearning for an existence more romantic than this” (as the narrator says about Mrs. Baines’s unexpected kinship with her defiant daughter). I’m enjoying both sisters equally so far: it doesn’t seem as if Bennett is setting them up as antagonists, despite their differences. When Sophia showed her first signs of rebellion, I wondered if she was an Edwardian cousin of Jane Eyre or Maggie Tulliver—but (again, so far) I don’t think so. Her restlessness seems more about her personality than about her circumstances: do you agree? (I loved Mrs. Baines’s attempt to treat Sophia’s “obstinacy and yearning” with castor oil.) Similarly, Constance’s quieter conduct doesn’t (so far) seem like mindless conformity, or capitulation to family or societal pressures: it’s just who she is.

I suppose its main function is to help establish the characters of the two sisters, who certainly reveal themselves as they squabble over the tooth: “the beauty of Sophia, the angelic tenderness of Constance, and the youthful, naïve, innocent charm of both of them, were transformed into something sinister and cruel.” A lot of these four first chapters is about setting up the contrast between them, which I know becomes a major structuring principle of the novel as it goes on. Chapter 4 makes this point really clearly, as it looks at how they have “grown up”: “The sisters were sharply differentiated,” the narrator remarks, in case we couldn’t tell. Constance’s name anticipates her more homely path, while Sophia’s hints at her “yearning for an existence more romantic than this” (as the narrator says about Mrs. Baines’s unexpected kinship with her defiant daughter). I’m enjoying both sisters equally so far: it doesn’t seem as if Bennett is setting them up as antagonists, despite their differences. When Sophia showed her first signs of rebellion, I wondered if she was an Edwardian cousin of Jane Eyre or Maggie Tulliver—but (again, so far) I don’t think so. Her restlessness seems more about her personality than about her circumstances: do you agree? (I loved Mrs. Baines’s attempt to treat Sophia’s “obstinacy and yearning” with castor oil.) Similarly, Constance’s quieter conduct doesn’t (so far) seem like mindless conformity, or capitulation to family or societal pressures: it’s just who she is. Two other features of these early chapters that contributed to my sense of the novel’s strangeness, and then I’ll close, because the point of this exercise is to start a conversation, not try to “cover” everything! First, the elephant. I did not expect an elephant at all, much less a thumbnail version of “Shooting an Elephant.” What’s up with the poor elephant, “whitewashed” and shot by “six men of the Rifle Corps”? The thing about a detail like this is that while you can always explain it away as a plot device—in this case a spectacle to get people out of the house and thus leave Sophia there to encounter Mr. Scales and neglect her father for that fatal interval—that doesn’t solve the problem of why the author used this specific plot device. It could have been anything: a fire, a runaway horse, a tightrope walker, a live elephant!

Two other features of these early chapters that contributed to my sense of the novel’s strangeness, and then I’ll close, because the point of this exercise is to start a conversation, not try to “cover” everything! First, the elephant. I did not expect an elephant at all, much less a thumbnail version of “Shooting an Elephant.” What’s up with the poor elephant, “whitewashed” and shot by “six men of the Rifle Corps”? The thing about a detail like this is that while you can always explain it away as a plot device—in this case a spectacle to get people out of the house and thus leave Sophia there to encounter Mr. Scales and neglect her father for that fatal interval—that doesn’t solve the problem of why the author used this specific plot device. It could have been anything: a fire, a runaway horse, a tightrope walker, a live elephant! Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil.

Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil. Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. (

Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. ( I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its

I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its  But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her.

But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her. “I am feeling wordless. I call it wu yu. It’s like I have lost my language.”

“I am feeling wordless. I call it wu yu. It’s like I have lost my language.” My confusion-slash-frustration arose from the elements around the novel’s simple plotline—or, arguably, missing from it. One example: The epigraph for each segment is a bit of dialogue from that segment. Why? Does that mean the rest of the section is just there to contextualize those lines? But what’s the value of reading them once out of context and once in it? It seemed both affected and repetitive. Another: What’s the significance of the directional names for the book’s larger divisions (West, South, Up, Down, etc.), which don’t really seem to apply to anything in them? Do they mean that the novel itself is about (finding? losing?) direction? Is disorientation a theme, a formal premise? Along those lines, are my largely unsuccessful attempts to discern meaning and patterns across the novel as a whole evidence that the book is doing what it wanted to, or that I’m reading it badly, or that it is not just impressionistic (artfully so) but incoherent (badly written, or imperfectly conceived)? Is my frustrated wish for the book to explain itself better actually the author’s desired effect, a challenge to my own reading habits? I do tend to value books that feel finished to me, rather than leaving large gaps for me to fill in myself. (Am I, in theory at least, “losing” one reading language and gaining another?)

My confusion-slash-frustration arose from the elements around the novel’s simple plotline—or, arguably, missing from it. One example: The epigraph for each segment is a bit of dialogue from that segment. Why? Does that mean the rest of the section is just there to contextualize those lines? But what’s the value of reading them once out of context and once in it? It seemed both affected and repetitive. Another: What’s the significance of the directional names for the book’s larger divisions (West, South, Up, Down, etc.), which don’t really seem to apply to anything in them? Do they mean that the novel itself is about (finding? losing?) direction? Is disorientation a theme, a formal premise? Along those lines, are my largely unsuccessful attempts to discern meaning and patterns across the novel as a whole evidence that the book is doing what it wanted to, or that I’m reading it badly, or that it is not just impressionistic (artfully so) but incoherent (badly written, or imperfectly conceived)? Is my frustrated wish for the book to explain itself better actually the author’s desired effect, a challenge to my own reading habits? I do tend to value books that feel finished to me, rather than leaving large gaps for me to fill in myself. (Am I, in theory at least, “losing” one reading language and gaining another?)

The books I read this week were all balanced on an emotional knife edge, mostly between being funny and being mournful but also, in the case of Nancy Mitford’s Love in a Cold Climate, between being funny and being awful. They all kept me engaged, but in the end it wasn’t a particularly nourishing stretch of reading, by which I mean they all left me feeling a little smaller and sadder than before, a result which is less about content or story (because of course a tragic book can, paradoxically, be very exhilarating to read) but about mood and tone.

The books I read this week were all balanced on an emotional knife edge, mostly between being funny and being mournful but also, in the case of Nancy Mitford’s Love in a Cold Climate, between being funny and being awful. They all kept me engaged, but in the end it wasn’t a particularly nourishing stretch of reading, by which I mean they all left me feeling a little smaller and sadder than before, a result which is less about content or story (because of course a tragic book can, paradoxically, be very exhilarating to read) but about mood and tone. The first of them, Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac, was a reread, though after such a long gap (I first read it in 2009) that many of its details felt new to me. When I commented on it here

The first of them, Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac, was a reread, though after such a long gap (I first read it in 2009) that many of its details felt new to me. When I commented on it here  Angela Huth’s Invitation to the Married Life was another reread, though I read it so long ago that I never even blogged about it—so, before 2007. That it—

Angela Huth’s Invitation to the Married Life was another reread, though I read it so long ago that I never even blogged about it—so, before 2007. That it— I hadn’t read Love in a Cold Climate before. A few years back I read The Pursuit of Love, which I

I hadn’t read Love in a Cold Climate before. A few years back I read The Pursuit of Love, which I  Even if we resolve that question in the novel’s favor, what should we make of the treatment of Boy Dougdale, also known as “the Lecherous Lecturer” because he preys on young girls? I say “preys” but, though most people in the book profess to find his conduct shocking, they also find it hilarious and they certainly don’t find it criminal. In fact, when Polly decides to marry him, everyone blames him, not for having sexually assaulted her when she was just fourteen, but for his having done “all those dreadful things” to her so that “now what she really wants most in the world is to roll and roll and roll about with him in a double bed.” Some of his acquaintances feel sorry for him being drawn into such an odd marriage, though there are some notes of judgment: “Pity him indeed! All he had to do was to leave little girls alone,” says Aunt Sadie, to which Uncle Davey replies “It’s a heavy price to pay for a bit of cuddling.” Later, after visiting Boy and Polly in Sicily, where they live in scandal-driven exile, Davey says

Even if we resolve that question in the novel’s favor, what should we make of the treatment of Boy Dougdale, also known as “the Lecherous Lecturer” because he preys on young girls? I say “preys” but, though most people in the book profess to find his conduct shocking, they also find it hilarious and they certainly don’t find it criminal. In fact, when Polly decides to marry him, everyone blames him, not for having sexually assaulted her when she was just fourteen, but for his having done “all those dreadful things” to her so that “now what she really wants most in the world is to roll and roll and roll about with him in a double bed.” Some of his acquaintances feel sorry for him being drawn into such an odd marriage, though there are some notes of judgment: “Pity him indeed! All he had to do was to leave little girls alone,” says Aunt Sadie, to which Uncle Davey replies “It’s a heavy price to pay for a bit of cuddling.” Later, after visiting Boy and Polly in Sicily, where they live in scandal-driven exile, Davey says It has been quiet at Novel Readings this week but that’s not because I haven’t been reading! It’s more that there hasn’t seemed to be much to say about the reading I’ve been doing. My recent novel reading has mostly been rereading: Rosy Thornton’s

It has been quiet at Novel Readings this week but that’s not because I haven’t been reading! It’s more that there hasn’t seemed to be much to say about the reading I’ve been doing. My recent novel reading has mostly been rereading: Rosy Thornton’s  Those are the novels I’ve reread for “fun” (though as I’ve said before, it is never 100% clear to me

Those are the novels I’ve reread for “fun” (though as I’ve said before, it is never 100% clear to me  The other reading I’ve been doing pretty steadily is also for research purposes, but with an eye to my teaching rather than my writing: I’m always gathering up references to new or (to me) unfamiliar scholarship in, around, and about “my” field, and at intervals I resolve to dig into it and see what else I could or should be talking about in the classroom, or just thinking about. Since the end of term I’ve been trying to go through 2-3 articles a day from that folder. This exercise tends to be equal parts exhilarating and exhausting: I enjoy feeling as if I’m learning new things or seeing familiar things from fresh angles, but I have long had

The other reading I’ve been doing pretty steadily is also for research purposes, but with an eye to my teaching rather than my writing: I’m always gathering up references to new or (to me) unfamiliar scholarship in, around, and about “my” field, and at intervals I resolve to dig into it and see what else I could or should be talking about in the classroom, or just thinking about. Since the end of term I’ve been trying to go through 2-3 articles a day from that folder. This exercise tends to be equal parts exhilarating and exhausting: I enjoy feeling as if I’m learning new things or seeing familiar things from fresh angles, but I have long had  I’m not sure what I’m going to read next “just” for myself. I bought Lonesome Dove as a summer treat, but I’m saving it for real summer weather: it looks perfect for reading on the deck. My book club’s next choice is Nancy Mitford’s The Blessing (we wanted something light for summer, and this was one of hers that none of us had already read)—but I don’t have it in hand yet. Of course, like everyone likely to read this post I have a number of unread books on my shelf (not as many as some of you have, though, I’m pretty sure!) but none of them look that tempting right now, which is probably why I haven’t read them already … Maybe I’ll reread something else I know I’ll like, if only to keep the temptation to order yet more new books at bay!

I’m not sure what I’m going to read next “just” for myself. I bought Lonesome Dove as a summer treat, but I’m saving it for real summer weather: it looks perfect for reading on the deck. My book club’s next choice is Nancy Mitford’s The Blessing (we wanted something light for summer, and this was one of hers that none of us had already read)—but I don’t have it in hand yet. Of course, like everyone likely to read this post I have a number of unread books on my shelf (not as many as some of you have, though, I’m pretty sure!) but none of them look that tempting right now, which is probably why I haven’t read them already … Maybe I’ll reread something else I know I’ll like, if only to keep the temptation to order yet more new books at bay! ‘And if you don’t take me,’ she said, ‘—well, when they put an end to your visits, what will you do then? Will you go on envying your sister’s life? Will you go on being a prisoner, in your own dark cell, forever?’

‘And if you don’t take me,’ she said, ‘—well, when they put an end to your visits, what will you do then? Will you go on envying your sister’s life? Will you go on being a prisoner, in your own dark cell, forever?’ I decided to reread Affinity because I have always wondered if I’d underestimated it; because I was in the mood for something plotty but smart and (sadly) Stuart Turton’s The Devil and the Dark Water, which I just read for my book club, looked promising but turned out not to be very good; and because I recently “attended” an interview with Waters as part of the London Library Book Festival, which of course was lively and fascinating. And here’s the thing. Affinity probably remains my least favorite Sarah Waters novel—but reading it this time, I was very conscious of just what a high bar that actually is! I was gripped from the first page and absorbed from beginning to end. I was surprised by it, because I read it long enough ago that I didn’t remember the details, and I was satisfied by it because its details are so well considered. Waters has the rare knack of making her historical research feel alive on the page, and somehow her characters feel true in a way that Turton’s never did for me. I don’t know if I could point to any specific example or highlight anything in particular that she does differently, but reading Waters right after reading Turton reminded me of the bit in Henry James’s “The Art of Fiction” when he notes that, on the subject of childhood, “with M. de Goncourt I should have for the most part to say No. With George Eliot, when she painted that country, I always said Yes.” I ended up saying “no” to Turton; Waters is a writer to whom I always say “yes.”

I decided to reread Affinity because I have always wondered if I’d underestimated it; because I was in the mood for something plotty but smart and (sadly) Stuart Turton’s The Devil and the Dark Water, which I just read for my book club, looked promising but turned out not to be very good; and because I recently “attended” an interview with Waters as part of the London Library Book Festival, which of course was lively and fascinating. And here’s the thing. Affinity probably remains my least favorite Sarah Waters novel—but reading it this time, I was very conscious of just what a high bar that actually is! I was gripped from the first page and absorbed from beginning to end. I was surprised by it, because I read it long enough ago that I didn’t remember the details, and I was satisfied by it because its details are so well considered. Waters has the rare knack of making her historical research feel alive on the page, and somehow her characters feel true in a way that Turton’s never did for me. I don’t know if I could point to any specific example or highlight anything in particular that she does differently, but reading Waters right after reading Turton reminded me of the bit in Henry James’s “The Art of Fiction” when he notes that, on the subject of childhood, “with M. de Goncourt I should have for the most part to say No. With George Eliot, when she painted that country, I always said Yes.” I ended up saying “no” to Turton; Waters is a writer to whom I always say “yes.” I’m not going to go into a lot of detail about the novel because one of its pleasures is how tense and twisty it is. I will say that one aspect of the novel that I especially enjoyed this time was how nicely Waters uses Little Dorrit to signal some of her own themes. Like Dickens’s novel, which Waters’ protagonist Margaret Prior reads with her mother, Affinity is set in a literal prison but is also very much about metaphorical prisons—social, psychological, and emotional. Much as Dickens does, Waters plays this idea out like a theme and variations, so that various meanings overlap and amplify each other. Margaret is free to come and go from London’s grim Millbank Prison, where she volunteers as a “Lady Visitor” offering company and comfort to the inmates, but she is unable to escape the crushing expectations and limitations of life as an unmarried woman whose interests and desires do not fit the life she is supposed to lead. When the novel’s action begins, she has already tried to commit suicide; thus life itself, to which she was unwillingly returned, is a kind of confinement, and her misery about her circumstances makes her eager to believe in the possibility of spirits that can pass back and forth over the threshold between life and death. Unable to express, much less claim, the love that might make her happy (for her sister-in-law Helen, for example), Margaret is also trapped by her loneliness. When she meets Selina Dawes, imprisoned at Millbank for fraud and assault, she gradually comes to believe that she has found the key that will set her free. Selina, in her turn, seeks liberation, from her literal cell but also from other forces the novel only gradually unveils for us.

I’m not going to go into a lot of detail about the novel because one of its pleasures is how tense and twisty it is. I will say that one aspect of the novel that I especially enjoyed this time was how nicely Waters uses Little Dorrit to signal some of her own themes. Like Dickens’s novel, which Waters’ protagonist Margaret Prior reads with her mother, Affinity is set in a literal prison but is also very much about metaphorical prisons—social, psychological, and emotional. Much as Dickens does, Waters plays this idea out like a theme and variations, so that various meanings overlap and amplify each other. Margaret is free to come and go from London’s grim Millbank Prison, where she volunteers as a “Lady Visitor” offering company and comfort to the inmates, but she is unable to escape the crushing expectations and limitations of life as an unmarried woman whose interests and desires do not fit the life she is supposed to lead. When the novel’s action begins, she has already tried to commit suicide; thus life itself, to which she was unwillingly returned, is a kind of confinement, and her misery about her circumstances makes her eager to believe in the possibility of spirits that can pass back and forth over the threshold between life and death. Unable to express, much less claim, the love that might make her happy (for her sister-in-law Helen, for example), Margaret is also trapped by her loneliness. When she meets Selina Dawes, imprisoned at Millbank for fraud and assault, she gradually comes to believe that she has found the key that will set her free. Selina, in her turn, seeks liberation, from her literal cell but also from other forces the novel only gradually unveils for us. What can these two imprisoned women mean to each other? What place is there for them in the world? I think the main reason I still find Affinity less exciting than Fingersmith is that its answer to these questions is [vague spoiler alert] sadder. Fingersmith goes to pretty bleak places, worse even (perhaps) than the “darks” of Millgate, but something luminous and beautiful emerges at the end. I’ve always remembered Affinity as dour by comparison, and this reading confirmed that impression; its grimness is not lifted in the same way by the sense of possibility, of escape, that the conclusion of Fingersmith offers. I might tentatively say that Affinity is more Gothic while Fingersmith is more Victorian, though like many such period or genre distinctions, that one may confuse more than it illuminates! At any rate, both novels are great reads and I’m glad I gave Affinity another chance. I might reread some of Waters’ other novels this summer: how is it possible that it has already been more than a decade since The Little Stranger came out?

What can these two imprisoned women mean to each other? What place is there for them in the world? I think the main reason I still find Affinity less exciting than Fingersmith is that its answer to these questions is [vague spoiler alert] sadder. Fingersmith goes to pretty bleak places, worse even (perhaps) than the “darks” of Millgate, but something luminous and beautiful emerges at the end. I’ve always remembered Affinity as dour by comparison, and this reading confirmed that impression; its grimness is not lifted in the same way by the sense of possibility, of escape, that the conclusion of Fingersmith offers. I might tentatively say that Affinity is more Gothic while Fingersmith is more Victorian, though like many such period or genre distinctions, that one may confuse more than it illuminates! At any rate, both novels are great reads and I’m glad I gave Affinity another chance. I might reread some of Waters’ other novels this summer: how is it possible that it has already been more than a decade since The Little Stranger came out? The headline, the article, it all points to one thing, the actress and her overshadowed child. The picture adds to the lie that I am a poor copy of my mother, that she was timeless, and I am not—the iconic gives birth to the merely human. But that was not how it was between us. That is not how we felt about ourselves.

The headline, the article, it all points to one thing, the actress and her overshadowed child. The picture adds to the lie that I am a poor copy of my mother, that she was timeless, and I am not—the iconic gives birth to the merely human. But that was not how it was between us. That is not how we felt about ourselves. Much as I was moved by both Katherine and Norah and engaged by the meticulously evoked historical and theatrical settings of the novel, though, I found the reading experience fragmented, the pieces of the novel difficult to integrate. Maybe if I reread it or thought harder about it I would understand why some of the bits and pieces are there, or why they are ordered in the novel as they are. I admit that right now I am a bit impatient with novelists who leave what feels like too much of that work up to me. I miss exposition, linearity, confidence that the novel as a form is robust enough to be “traditional” in these ways and still new. Actress is not by any means as conspicuously piecemeal as some recent novels, and it isn’t really minimalist, just condensed and somewhat episodic. Maybe it should be enough that it made me feel for the characters, and that Katherine especially seemed vivid enough to be more than a type—though I did feel at times that her pathos and melodrama and ‘madness’ (as her daughter characterizes it) verged on cliché. Is it the red hair (acquired to boost her ‘Irish’ identity) that meant I kept picturing her as Beth Harmon in The Queen’s Gambit? That, and her drinking and her flamboyance and her misery and her endless performance as a character in her own drama: that she lacks (or can’t rely on) her authentic self is part of Katherine’s tragedy, but it also made her poor company, and Norah is similarly, if more quietly, histrionic.

Much as I was moved by both Katherine and Norah and engaged by the meticulously evoked historical and theatrical settings of the novel, though, I found the reading experience fragmented, the pieces of the novel difficult to integrate. Maybe if I reread it or thought harder about it I would understand why some of the bits and pieces are there, or why they are ordered in the novel as they are. I admit that right now I am a bit impatient with novelists who leave what feels like too much of that work up to me. I miss exposition, linearity, confidence that the novel as a form is robust enough to be “traditional” in these ways and still new. Actress is not by any means as conspicuously piecemeal as some recent novels, and it isn’t really minimalist, just condensed and somewhat episodic. Maybe it should be enough that it made me feel for the characters, and that Katherine especially seemed vivid enough to be more than a type—though I did feel at times that her pathos and melodrama and ‘madness’ (as her daughter characterizes it) verged on cliché. Is it the red hair (acquired to boost her ‘Irish’ identity) that meant I kept picturing her as Beth Harmon in The Queen’s Gambit? That, and her drinking and her flamboyance and her misery and her endless performance as a character in her own drama: that she lacks (or can’t rely on) her authentic self is part of Katherine’s tragedy, but it also made her poor company, and Norah is similarly, if more quietly, histrionic.