“This is me trying,” I said in a post back in May. I was trying to read again, and also to write about my reading again. I have been trying even harder recently, though with mixed success: I’m still abandoning more books than I used to, and watching TV instead of reading because it’s more quickly and easily distracting, but I’ve also written up some of the books I have managed to read in something more like the old spirit of “just say what you think and don’t second guess it.” What a liberating feeling that was, back in the early days of this blog, and it really has continued to be freeing—this space, while in some senses a public one, is my space, a place where I just write what I want to.

“This is me trying,” I said in a post back in May. I was trying to read again, and also to write about my reading again. I have been trying even harder recently, though with mixed success: I’m still abandoning more books than I used to, and watching TV instead of reading because it’s more quickly and easily distracting, but I’ve also written up some of the books I have managed to read in something more like the old spirit of “just say what you think and don’t second guess it.” What a liberating feeling that was, back in the early days of this blog, and it really has continued to be freeing—this space, while in some senses a public one, is my space, a place where I just write what I want to.

I was surprised, after Owen’s death, by how strongly I wanted to write about it. Words and phrases came to me and would echo in my head until I found a place for them. That still happens, but as time keeps relentlessly passing the sameness of my grief feels like a reason to write less about it; I have been trying, here anyway. What else is there to say, after all? My son is still dead; I am still grieving him daily and deeply. And yet things aren’t exactly the same: how could they be, eight months later? One of the strangest things for me now—and here I think I am understanding better what Denise Riley meant when she talked about her grief in terms of dropping out of time—is that the passing time suddenly feels less linear than circular, as if instead of its carrying me further and further away from Owen (unwillingly left behind in his timelessness, as Riley puts it), it is bringing me back, impossibly, to a time when he was right here with us, because it was just (just!) last summer that, after hardly seeing each other in person for the first year of the pandemic, we had begun visiting again, and just (just!) last August that he came to share his finished Hackenbush video with us. He was also starting classes again at Dalhousie; things seemed to be looking up on all fronts. Those days are so vivid, so immediate, in my memory, that it makes me literally dizzy sometimes when I bring myself back to this moment, this August, the start of this new term.

![]() Something else that’s different is how emotionally confusing and therefore exhausting I’m finding the present. The early days of grief are awful but absolute, almost simple, I realize now: there are no options, no expectations, for anything besides mourning. I have learned so much about grief since then, from experience but also from others, and from reading. One thing I’ve learned is that “it takes time” doesn’t mean that with time the grief lessens; it means something more like you get used to living with it, you learn to walk around with it, but it’s still there, fierce and painful and disorienting. Something else I’ve learned is that grief changes your relationship with happiness. I’ve read a lot of poetry in the last few months, taking comfort in finding words “in the shape of [my] wounds” (in Sean Thomas Dougherty’s phrase). I like this poem by W. S. Merwin, which captures both the relief of finding words for my pain and the pain of encountering “the joy of the world” when it feels impossible to share in it.

Something else that’s different is how emotionally confusing and therefore exhausting I’m finding the present. The early days of grief are awful but absolute, almost simple, I realize now: there are no options, no expectations, for anything besides mourning. I have learned so much about grief since then, from experience but also from others, and from reading. One thing I’ve learned is that “it takes time” doesn’t mean that with time the grief lessens; it means something more like you get used to living with it, you learn to walk around with it, but it’s still there, fierce and painful and disorienting. Something else I’ve learned is that grief changes your relationship with happiness. I’ve read a lot of poetry in the last few months, taking comfort in finding words “in the shape of [my] wounds” (in Sean Thomas Dougherty’s phrase). I like this poem by W. S. Merwin, which captures both the relief of finding words for my pain and the pain of encountering “the joy of the world” when it feels impossible to share in it.

Words

When the pain of the world finds words

they sound like joy

and often we follow them

with our feet of earth

and learn them by heart

but when the joy of the world finds words

they are painful

and often we turn away

with our hands of water

I am trying—to read, to write, to be—but it’s hard and uncomfortable and often I would rather not. Turning away is easier. Still, time keeps passing, and soon I won’t be able to default to comfortless passivity: next week, I will be back in the classroom.

The vast metaphor which most faithfully represents this fathomless ordeal . . . is that of Dante, and his all-too-familiar lines still arrest the imagination with their augury of the unknowable, the black struggle to come:

The vast metaphor which most faithfully represents this fathomless ordeal . . . is that of Dante, and his all-too-familiar lines still arrest the imagination with their augury of the unknowable, the black struggle to come: I read Darkness Visible on the recommendation of a friend who knew that I have been struggling to understand Owen’s decision to end his life from his point of view, not just because he did not share many details of his struggle but because I have never experienced depression myself—sadness, yes, and now grief, but these are far from the same thing.

I read Darkness Visible on the recommendation of a friend who knew that I have been struggling to understand Owen’s decision to end his life from his point of view, not just because he did not share many details of his struggle but because I have never experienced depression myself—sadness, yes, and now grief, but these are far from the same thing. Styron dislikes the term “depression”: “melancholia,” he thinks, “would still appear to be a far more apt and evocative word for the blacker forms of the disorder,” whereas “depression,” bland and innocuous sounding, inhibits understanding “of the horrible intensity of the disease when out of control.” Styron carefully chronicles his own descent into the worst of it, frankly examining the role of his drinking (which he believes actually held the depression at bay for some time), the onset of “a kind of numbness” in which his own body began to feel unfamiliar to him, and then a pattern of “anxiety, agitation, unfocused dread” leading to “a suffocating gloom” and “an immense and aching solitude.” He recounts the medications he took (this was before the widespread use of today’s most frequently prescribed antidepressants), the therapy he finally sought out, and his eventual hospitalization, which in his case proved life-saving, mostly because (as he tells it) it bought him precious time:

Styron dislikes the term “depression”: “melancholia,” he thinks, “would still appear to be a far more apt and evocative word for the blacker forms of the disorder,” whereas “depression,” bland and innocuous sounding, inhibits understanding “of the horrible intensity of the disease when out of control.” Styron carefully chronicles his own descent into the worst of it, frankly examining the role of his drinking (which he believes actually held the depression at bay for some time), the onset of “a kind of numbness” in which his own body began to feel unfamiliar to him, and then a pattern of “anxiety, agitation, unfocused dread” leading to “a suffocating gloom” and “an immense and aching solitude.” He recounts the medications he took (this was before the widespread use of today’s most frequently prescribed antidepressants), the therapy he finally sought out, and his eventual hospitalization, which in his case proved life-saving, mostly because (as he tells it) it bought him precious time: Not always, of course, and as a book like this can only be written by just such a survivor, it is bound to tilt more towards optimism than might in other cases seem warranted. From his own experience, Styron appreciates that convincing a depressed person (usually “in a state of unrealistic hopelessness”) to see things as he now does is “a tough job”:

Not always, of course, and as a book like this can only be written by just such a survivor, it is bound to tilt more towards optimism than might in other cases seem warranted. From his own experience, Styron appreciates that convincing a depressed person (usually “in a state of unrealistic hopelessness”) to see things as he now does is “a tough job”: True to his own experience, though, Styron does not end on this gloomy note, but on a more uplifting one:

True to his own experience, though, Styron does not end on this gloomy note, but on a more uplifting one: July was not a very good reading month for me. By habit and on principle I usually finish most of the books I start, at least if I have any reason to think they are worth a bit of effort if it’s needed. In July, however, I not only didn’t even start many books (not by my usual standards, anyway) but I set aside almost as many books as I completed—Bloomsbury Girls (which hit all my sweet spots in theory but fell painfully flat in practice), Gilead (a reread I was enthusiastic about at first but just could not persist with), A Ghost in the Throat (which I will try again, as I liked its voice—what I struggled with was its essentialism and its somewhat miscellaneous or wandering structure). I already mentioned Andrew Miller’s Oxygen and Monica Ali’s Love Marriage, both of which I finished and enjoyed,

July was not a very good reading month for me. By habit and on principle I usually finish most of the books I start, at least if I have any reason to think they are worth a bit of effort if it’s needed. In July, however, I not only didn’t even start many books (not by my usual standards, anyway) but I set aside almost as many books as I completed—Bloomsbury Girls (which hit all my sweet spots in theory but fell painfully flat in practice), Gilead (a reread I was enthusiastic about at first but just could not persist with), A Ghost in the Throat (which I will try again, as I liked its voice—what I struggled with was its essentialism and its somewhat miscellaneous or wandering structure). I already mentioned Andrew Miller’s Oxygen and Monica Ali’s Love Marriage, both of which I finished and enjoyed,  Ali Smith’s how to be both was a mixed experience for me. My copy began with the contemporary story (as you may know, two versions were published), and it read easily for me and was quite engaging, in the same way that the

Ali Smith’s how to be both was a mixed experience for me. My copy began with the contemporary story (as you may know, two versions were published), and it read easily for me and was quite engaging, in the same way that the  Another reread for me in July was Yiyun Li’s

Another reread for me in July was Yiyun Li’s  No, it’s not an elegy, I thought. No parent should write a child’s elegy.

No, it’s not an elegy, I thought. No parent should write a child’s elegy. July 2019

July 2019

The mind is not only its own place, as Milton’s Satan observes, but it can also be a pretty strange place, or mine can anyway, especially these days. Today, for example, it has been six months (six months!) since Owen’s death, and what keeps running through my mind is a mangled version of lines from “The Charge of the Light Brigade”: “half a year, half a year, half a year onward, into the valley of death …” and then nothing comes next, it just starts over, because not only (of course) are these not the poem’s actual words but I don’t know what words of my own should follow to finish the thought.

The mind is not only its own place, as Milton’s Satan observes, but it can also be a pretty strange place, or mine can anyway, especially these days. Today, for example, it has been six months (six months!) since Owen’s death, and what keeps running through my mind is a mangled version of lines from “The Charge of the Light Brigade”: “half a year, half a year, half a year onward, into the valley of death …” and then nothing comes next, it just starts over, because not only (of course) are these not the poem’s actual words but I don’t know what words of my own should follow to finish the thought.

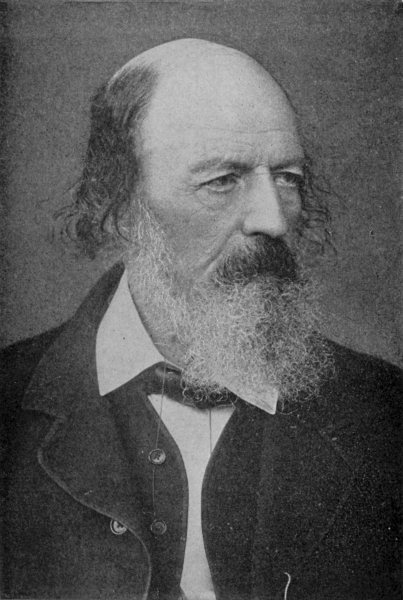

It’s hard to imagine a poem that is less apt, for the occasion or for my feelings about it. (I hate this poem, actually, though I love so much of Tennyson’s poetry.*) I can’t think of any reason for this mental hiccup besides the generally cluttered condition of my mind thanks to two years of COVID isolation and now six months (six months!) of grieving. Six months is half a year—half a year! I have to keep repeating it to make myself believe it, and it’s probably just the repetition and rhythm of that phrase that trips my tired brain over into Tennyson’s too-familiar verse.

Half a year. That stretch of time seemed unfathomably long to me in the first

It’s hard to imagine a poem that is less apt, for the occasion or for my feelings about it. (I hate this poem, actually, though I love so much of Tennyson’s poetry.*) I can’t think of any reason for this mental hiccup besides the generally cluttered condition of my mind thanks to two years of COVID isolation and now six months (six months!) of grieving. Six months is half a year—half a year! I have to keep repeating it to make myself believe it, and it’s probably just the repetition and rhythm of that phrase that trips my tired brain over into Tennyson’s too-familiar verse.

Half a year. That stretch of time seemed unfathomably long to me in the first  How should the thought finish? As I walk through the valley of the shadow of Owen’s death, I have no sure path or comfort. All I know, or hope I know, is that at some point, in some way, I will emerge from it and he will not. Six months ago today, devastated beyond any words of my own, I copied stanzas from Tennyson’s In Memoriam into my journal. It remains the best poem I know about grief, though as it turns towards a resolution not available to me, maybe it’s more accurate to say that it contains the best poetry I know about grief. (For that, I can forgive him the jingoistic tedium of “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”) This has always been my favorite section—it is so powerful in its stark simplicity:

How should the thought finish? As I walk through the valley of the shadow of Owen’s death, I have no sure path or comfort. All I know, or hope I know, is that at some point, in some way, I will emerge from it and he will not. Six months ago today, devastated beyond any words of my own, I copied stanzas from Tennyson’s In Memoriam into my journal. It remains the best poem I know about grief, though as it turns towards a resolution not available to me, maybe it’s more accurate to say that it contains the best poetry I know about grief. (For that, I can forgive him the jingoistic tedium of “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”) This has always been my favorite section—it is so powerful in its stark simplicity:

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937)

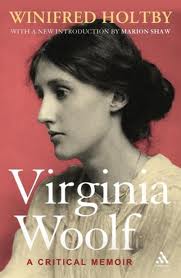

Not a happy summer. That is all the materials for happiness; & nothing behind. If Julian had not died—still an incredible sentence to write—our happiness might have been profound . . . but his death—that extraordinary extinction—drains it of substance. (Woolf, Diaries, 26 September, 1937) I haven’t written much new about Woolf yet this year (I’ve been focusing on other pieces of my project) but I have thought about her a lot—specifically, I have thought a lot about her suicide. One of my favorite things about Holtby’s Critical Memoir of Woolf is that Holtby died before Woolf did and so no shadow darkens her celebration of

I haven’t written much new about Woolf yet this year (I’ve been focusing on other pieces of my project) but I have thought about her a lot—specifically, I have thought a lot about her suicide. One of my favorite things about Holtby’s Critical Memoir of Woolf is that Holtby died before Woolf did and so no shadow darkens her celebration of  With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

With Woolf on my mind again thanks to Queyras’s book, I picked up Volume 5 of her diary (1936-1941), which I have to hand because it covers the time she was working on The Years and Three Guineas. So much is always happening in her diaries and letters: you can dip into them anywhere and find something vital, interesting, fertile for thought. This volume of the diary also includes the lead-up to war and then her experience of the Blitz, and the final entries before her suicide, which are inevitably strange and poignant—even more so to me now. Leafing through its pages this time, though, it was the entries around the death of her nephew Julian Bell in July 1937 that drew me in: Woolf as mourner, not mourned.

I’ve assigned Margaret Oliphant’s Autobiography many times over the years in the graduate seminar I’ve offered on Victorian women writers. I read it first myself in a similar seminar offered by Dorothy Mermin at Cornell: I realized later that this was while she was working on her excellent book

I’ve assigned Margaret Oliphant’s Autobiography many times over the years in the graduate seminar I’ve offered on Victorian women writers. I read it first myself in a similar seminar offered by Dorothy Mermin at Cornell: I realized later that this was while she was working on her excellent book

Twenty-one years pass between these painful sections and the next section of the Autobiography, and in that gap is, as she notes, “a little lifetime.” “I have just been rereading it all with tears,” she says, “sorry, very sorry for that poor little soul who has lived through so much since.” Writing those words in 1885, she had no idea how much more sorrow lay ahead. First came the death of her son Cyril in 1890 (“I have been permitted to do everything for him, to wind up his young life, to accept the thousand and thousand disappointments and thoughts of what might have been”), and then in 1894, the death of her son Cecco (“The younger after the elder and on this earth I have no son—I have no child. I am a mother childless”). “What have I left now?” she laments. “My work is over, my house is desolate. I am empty of all things.” In her despair (“It is not in me to take a dose and end it. Oh I wish it were”), her vast literary output brings her no comfort: “nobody thinks that the few books I will leave behind me count for anything.”

Twenty-one years pass between these painful sections and the next section of the Autobiography, and in that gap is, as she notes, “a little lifetime.” “I have just been rereading it all with tears,” she says, “sorry, very sorry for that poor little soul who has lived through so much since.” Writing those words in 1885, she had no idea how much more sorrow lay ahead. First came the death of her son Cyril in 1890 (“I have been permitted to do everything for him, to wind up his young life, to accept the thousand and thousand disappointments and thoughts of what might have been”), and then in 1894, the death of her son Cecco (“The younger after the elder and on this earth I have no son—I have no child. I am a mother childless”). “What have I left now?” she laments. “My work is over, my house is desolate. I am empty of all things.” In her despair (“It is not in me to take a dose and end it. Oh I wish it were”), her vast literary output brings her no comfort: “nobody thinks that the few books I will leave behind me count for anything.” She kept writing, though, not just the Autobiography—which she reconceived somewhat, pragmatically, once it was no longer intended for her children, as something lighter and more anecdotal—but also more fiction, including her excellent ghost story “The Library Window,” recently reprinted by Broadview. It’s not hard to understand the appeal of ghost stories to a mother whose beloved children would have been there but not there every waking minute. I know what that’s like.

She kept writing, though, not just the Autobiography—which she reconceived somewhat, pragmatically, once it was no longer intended for her children, as something lighter and more anecdotal—but also more fiction, including her excellent ghost story “The Library Window,” recently reprinted by Broadview. It’s not hard to understand the appeal of ghost stories to a mother whose beloved children would have been there but not there every waking minute. I know what that’s like.