Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.

As anticipated, my first two books of 2020 were Kate Clayborn’s Love Lettering and Tana French’s The Witch Elm. They could hardly be more different, but of their kinds, they are both, I think, excellent.

Love Lettering has many of the same qualities that have made Clayborn’s previous books–the ‘Chance of a Lifetime’ trilogy–my favorite contemporary romance series. Interestingly (to me, anyway!), these are qualities that actually dulled the books’ impact at first. Clayborn gives her characters a lot of specificity, both in their personalities and in their activities. This means a lot of backstory and also a lot of neepery (which, as I’ve figured out, is one of my favorite things). In Beginner’s Luck, for instance, one of the protagonists, Kit, is a lab technician, which I suppose might sound a bit dry, but Clayborn does a good job conveying the interest and satisfaction she finds in her job, as well as explaining the scientific work she is also involved in. In the same novel, the other lead character, Ben, helps out at his father’s salvage business–again, maybe not the first thing you’d think of as a romantic setting, but I really enjoy the details about the bits and pieces of lights and fixtures and furniture and their restoration. All this stuff isn’t just background, though: Clayborn is really deft at assembling elements that both further her story and work symbolically within it. In Beginner’s Luck, Ben is puttering away at re-assembling an elaborate chandelier: by the end of the novel it’s clear that putting things back together is what both he and Kit are struggling to do, in their different ways.

The first time I read Beginner’s Luck I felt that there was so much going on that it got a bit distracting. Maybe this has something to do with my expectations for romance: though there is a lot of emotional intensity in Clayborn’s novels, the central relationship is embedded in a lot of what seemed like padding. It turns out, though, that for me anyway this is exactly what makes her books fun to reread, as more of the novels’ patterns–the connections between their parts–become clearer over time. At the same time, it’s the emotional intensity that means I give a pass to what might otherwise bother me about them, which is that the love story relies (more so in the second and third books in the trilogy than the first) on an initial set-up that seems, if you think about it hard at all, pretty contrived or unlikely. This is especially true of Luck of the Draw, which has nonetheless turned out to be my favorite of the trilogy.

The first time I read Beginner’s Luck I felt that there was so much going on that it got a bit distracting. Maybe this has something to do with my expectations for romance: though there is a lot of emotional intensity in Clayborn’s novels, the central relationship is embedded in a lot of what seemed like padding. It turns out, though, that for me anyway this is exactly what makes her books fun to reread, as more of the novels’ patterns–the connections between their parts–become clearer over time. At the same time, it’s the emotional intensity that means I give a pass to what might otherwise bother me about them, which is that the love story relies (more so in the second and third books in the trilogy than the first) on an initial set-up that seems, if you think about it hard at all, pretty contrived or unlikely. This is especially true of Luck of the Draw, which has nonetheless turned out to be my favorite of the trilogy.

It is also definitely true of Love Lettering, where the relationship between the main characters, Meg and Reid, depends on his implausibly accepting an invitation that I can’t quite imagine anyone actually extending to a virtual stranger. However! Once they get started, their slow-growing friendship plays out in a beautifully nuanced way, their uneasy unfamiliarity teetering bit by bit into trust, pleasure, and of course, ultimately, love. Here too there’s a lot going on in context and character development, especially around Meg’s work doing hand lettering. Clayborn gives us a lot of detail about that work, but it never feels like she’s doing the dreaded “info-dump”: instead, Meg’s interest, her vocation, permeates her first-person narration. She sees lettering everywhere, both literally and when people talk to her–or when she and Reid kiss for the first time:

He shifts, lets his lips rest softly against my cheekbone, and instead of pressing them there, he rubs them back and forth once, as light as a strand of my own hair in the wind, and I see that word, too, drawn in the same pink that’s the color of my natural blush, the pink I turn when I’m warm or embarrassed or aroused. The t, the w, the o, all of them a heavily sloped italic. All of them on the way to somewhere.

It’s a kind of sensual synesthesia that is also elicited for her in a more aesthetic and intellectual way by her relationship with New York–which the novel is also a love letter to, as Meg and Reid’s romance unfolds as they explore the streets in search of inspiration in its billboards, awnings, and facades. Love Lettering turns out to be a novel all about reading signs, literal but also metaphorical and personal; this concept ties together its various subplots, as does the characters’ related struggle to express themselves clearly–to signal their own meaning. My only complaint about the novel is that the ending, which includes a long-deferred revelation about Reid, seemed both a bit rushed and a bit out of sync with the mood or style of the rest of the book. That revelation is also the reason we don’t get the alternating points of view Clayborn used in all three of her previous books. I liked Meg a lot, but it felt a bit odd for a romance to be so completely one-sided. Now that I know everything, however, I will be able to infer a lot more about what is really going on with Reid when I reread it, which I am bound to do before long.

The Witch Elm has been written about a lot elsewhere; of the reviews I’ve read, I think Laura Miller’s in Slate comes closest to what I thought about it. I know some people have found it too long or too purposeless, for its first half at least, and so not particularly gripping. Maureen Corrigan in the Washington Post concludes her actually fairly positive review a bit crushingly: “I’d say that without any “bang, bang” for hundreds of pages, “The Witch Elm” becomes “boring, boring.” I definitely did not find it boring! Toby’s voice worked for me from the start, though having read Tana French before I knew better than to take him completely at face value. I liked the patient progress of the story through the initial harrowing attack on Toby to the muted Gothic atmosphere of the Ivy House. Once the skull turned up I had (unusually, for me!) lots of theories about how it got there and who was implicated–and French teased me with plenty of hints and possibilities that fit and then contradicted each of them. Toby’s wavering sense of self brought layers to the novel, both philosophical and psychological. “They’re unsettled and they’re frightened,” Uncle Hugo says about the people who hire him to research their genealogies after unexpected DNA results; “They’re afraid that they’re not who they always thought they were, and they want me to find them reassurance. And we both know it might not turn out that way.” That’s Toby’s situation too, eventually, trying to figure out the truth about himself when other people’s accounts of him don’t square with his own. For him too, the result may not be reassuring–but what French conveys so well is that his very craving for stability, for confirmation, for certainty about his own identity, is itself a potent destructive force.

The Witch Elm has been written about a lot elsewhere; of the reviews I’ve read, I think Laura Miller’s in Slate comes closest to what I thought about it. I know some people have found it too long or too purposeless, for its first half at least, and so not particularly gripping. Maureen Corrigan in the Washington Post concludes her actually fairly positive review a bit crushingly: “I’d say that without any “bang, bang” for hundreds of pages, “The Witch Elm” becomes “boring, boring.” I definitely did not find it boring! Toby’s voice worked for me from the start, though having read Tana French before I knew better than to take him completely at face value. I liked the patient progress of the story through the initial harrowing attack on Toby to the muted Gothic atmosphere of the Ivy House. Once the skull turned up I had (unusually, for me!) lots of theories about how it got there and who was implicated–and French teased me with plenty of hints and possibilities that fit and then contradicted each of them. Toby’s wavering sense of self brought layers to the novel, both philosophical and psychological. “They’re unsettled and they’re frightened,” Uncle Hugo says about the people who hire him to research their genealogies after unexpected DNA results; “They’re afraid that they’re not who they always thought they were, and they want me to find them reassurance. And we both know it might not turn out that way.” That’s Toby’s situation too, eventually, trying to figure out the truth about himself when other people’s accounts of him don’t square with his own. For him too, the result may not be reassuring–but what French conveys so well is that his very craving for stability, for confirmation, for certainty about his own identity, is itself a potent destructive force.

My only quibble with The Witch Elm is that the story about the skull in the tree eventually comes out in a really dull way (narratively speaking – the facts are plenty shocking): Toby just gets told it all in a long and inadequately motivated ‘reveal’ scene. I expected the case to be ‘solved’ in some more subtle and artful way. I realize that the novel is not, really, centered on that whodunit aspect but is actually about Toby–who he is, what he has done or not done, what has enabled him to live and think and ignore and forget the way he has. Still, that bit fell flat for me. Things took another dramatic turn soon after, though, and the novel’s denouement overall was very satisfactory.

So there we are: two new books for the new year, both good ones. What’s next? Well, for one, Pride and Prejudice, which I start with my 19th-century fiction class on Friday.

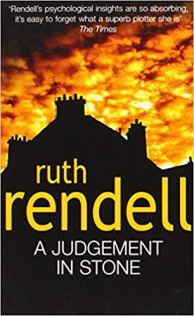

Is it true that Eunice Parchman–and her accomplice, the same friend the unknowing Coverdales tried to keep away from their home–killed this hapless family “because she could not read or write”? Rendell’s striking opening is as much provocation as declaration, I think. It is certainly true that Eunice’s illiteracy haunts, shames, and distorts her life. It is easy to imagine a version of her story in which, as a result, we pity her and direct our antipathy at a society that repeatedly fails her–fails to educate her, fails to support her, fails to make it safe for her to overcome this debilitating disadvantage–while she retreats into the safety of suspicious solitude:

Is it true that Eunice Parchman–and her accomplice, the same friend the unknowing Coverdales tried to keep away from their home–killed this hapless family “because she could not read or write”? Rendell’s striking opening is as much provocation as declaration, I think. It is certainly true that Eunice’s illiteracy haunts, shames, and distorts her life. It is easy to imagine a version of her story in which, as a result, we pity her and direct our antipathy at a society that repeatedly fails her–fails to educate her, fails to support her, fails to make it safe for her to overcome this debilitating disadvantage–while she retreats into the safety of suspicious solitude: Rendell’s opening line is thus a bit of a feint, I think: it seems to set up a novel about the consequences of social and educational failures, but unlike, say, Dickens’s account of Magwitch’s history in Great Expectations, she doesn’t really account for Eunice’s criminality on those terms alone, leaving us to point the finger at ourselves for creating an uncaring system that generates criminals where there should have been (and still could be) a caring human being. Eunice seems irredeemable; Rendell doesn’t make a convincing case that she would have been a different person–and the Coverdales would have lived–if only she could read the printed word. It’s hard to be sure, though, and maybe that’s the question Rendell means to leave with her readers.

Rendell’s opening line is thus a bit of a feint, I think: it seems to set up a novel about the consequences of social and educational failures, but unlike, say, Dickens’s account of Magwitch’s history in Great Expectations, she doesn’t really account for Eunice’s criminality on those terms alone, leaving us to point the finger at ourselves for creating an uncaring system that generates criminals where there should have been (and still could be) a caring human being. Eunice seems irredeemable; Rendell doesn’t make a convincing case that she would have been a different person–and the Coverdales would have lived–if only she could read the printed word. It’s hard to be sure, though, and maybe that’s the question Rendell means to leave with her readers.

On the other hand, I did appreciate the metafictional commentary on the genre scattered throughout Magpie Murders, though it was (as far as I could tell) somewhat gratuitous or incidental to the novel(s). If the stories Horowitz was telling subverted expectations more than they do, or if their resolutions turned in some way on critiquing the ubiquity of murders on page and screen or the idea that anything about crime is in any way “cozy,” then the whole novel would (for me) have taken on much greater significance. Still, he raises good points about the perverse gratifications of the form even as he unapologetically offers them up, twice over. “I don’t understand it,” says Detective Superintendent Locke when Susan meets with him to discuss her questions about Conway’s death. “All these murders on TV–”

On the other hand, I did appreciate the metafictional commentary on the genre scattered throughout Magpie Murders, though it was (as far as I could tell) somewhat gratuitous or incidental to the novel(s). If the stories Horowitz was telling subverted expectations more than they do, or if their resolutions turned in some way on critiquing the ubiquity of murders on page and screen or the idea that anything about crime is in any way “cozy,” then the whole novel would (for me) have taken on much greater significance. Still, he raises good points about the perverse gratifications of the form even as he unapologetically offers them up, twice over. “I don’t understand it,” says Detective Superintendent Locke when Susan meets with him to discuss her questions about Conway’s death. “All these murders on TV–” That, she concludes, is “why Magpie Murders was so bloody irritating”–unfinished as it is when she first reads it. For me, though, the end of Horowitz’s Magpie Murders did not provide much satisfaction. The dotting of the i‘s and the crossing of the t’s seemed to show up the whole elaborate exercise as artificial, an impressive display of plotting but little to feed any deeper curiosity. I prefer my crime fiction more character driven, and also more embroiled in social and political contexts. I know Horowitz can write that kind of mystery, because he wrote

That, she concludes, is “why Magpie Murders was so bloody irritating”–unfinished as it is when she first reads it. For me, though, the end of Horowitz’s Magpie Murders did not provide much satisfaction. The dotting of the i‘s and the crossing of the t’s seemed to show up the whole elaborate exercise as artificial, an impressive display of plotting but little to feed any deeper curiosity. I prefer my crime fiction more character driven, and also more embroiled in social and political contexts. I know Horowitz can write that kind of mystery, because he wrote

I didn’t start enjoying the novel more just because the plot became more engrossing, though it did–or because the prose became more pleasurable, because it really didn’t. The other thing that happened was I got used to the slow pace and came to appreciate all the cultural context I was getting through what initially seemed like digressions. It’s true that all the many (many!) descriptions of meals aren’t strictly necessary to the plot, but they certainly added to my sense of what life in Shanghai in the 1990s was like, as did the meticulous accounts of where and how people live:

I didn’t start enjoying the novel more just because the plot became more engrossing, though it did–or because the prose became more pleasurable, because it really didn’t. The other thing that happened was I got used to the slow pace and came to appreciate all the cultural context I was getting through what initially seemed like digressions. It’s true that all the many (many!) descriptions of meals aren’t strictly necessary to the plot, but they certainly added to my sense of what life in Shanghai in the 1990s was like, as did the meticulous accounts of where and how people live: I also really enjoyed the role of Chen’s poetry in his life and in his case–and in the case against him. The idea that his elusive (and allusive) verses harbor subversive messages at once works with the intense suspicion shown by loyal Party members towards anything suggestive of a “Western bourgeois decadent lifestyle” and seemed to me a sly play on the literary difficulty of modernist poetry and the challenge of figuring out what it means. Poring over Chen’s poem “Night Talk,” Zhang wonders if the phrase “mind’s square” is a reference to Tiananmen Square:

I also really enjoyed the role of Chen’s poetry in his life and in his case–and in the case against him. The idea that his elusive (and allusive) verses harbor subversive messages at once works with the intense suspicion shown by loyal Party members towards anything suggestive of a “Western bourgeois decadent lifestyle” and seemed to me a sly play on the literary difficulty of modernist poetry and the challenge of figuring out what it means. Poring over Chen’s poem “Night Talk,” Zhang wonders if the phrase “mind’s square” is a reference to Tiananmen Square:

Seating himself in the long chair, his thin hands gripping the arms, he seemed to relax watchfulness. Tired, I thought, and noticed the hint of purple in the shadows of the deep-set eyes, the tension of flesh across narrow cheekbones. Then, quickly, hailing into my mind the scarlet caution signal, I banished quick and foolish tenderness. Dolls and dames, I said to myself; we’re all dolls and dames to him.

Seating himself in the long chair, his thin hands gripping the arms, he seemed to relax watchfulness. Tired, I thought, and noticed the hint of purple in the shadows of the deep-set eyes, the tension of flesh across narrow cheekbones. Then, quickly, hailing into my mind the scarlet caution signal, I banished quick and foolish tenderness. Dolls and dames, I said to myself; we’re all dolls and dames to him. Laura would pose some pedagogical problems of its own, not because it’s creepy (though it is deliciously twisty) but because its first narrator, Waldo Lydecker, is completely insufferable. I actually didn’t know when I began the novel that it would have multiple narrators and I wasn’t sure I was up for 200 pages of his self-conscious pomposity. “I am given,” he tells us,

Laura would pose some pedagogical problems of its own, not because it’s creepy (though it is deliciously twisty) but because its first narrator, Waldo Lydecker, is completely insufferable. I actually didn’t know when I began the novel that it would have multiple narrators and I wasn’t sure I was up for 200 pages of his self-conscious pomposity. “I am given,” he tells us, In addition to the clever plot and the pleasures of the multiple narrators, Laura seems to me particularly interesting for (no surprise!) Laura herself, and for the way the other characters attempt to fix her identity in a way that accords with their assumptions about women. Hard-boiled or noir fiction famously tends to limit women to specific roles: victim, dame, femme fatale. Caspary and Laura are both aware of the way women get cast into roles that restrict their individuality and define them in relation to men; Laura’s resistance to this is one of the factors that puts her life in danger. “You are not dead,” another character says to her at one point; “you are a violent, living, bloodthirsty woman.” How much of that sentence is true? It depends, quite literally, on whose story you accept.

In addition to the clever plot and the pleasures of the multiple narrators, Laura seems to me particularly interesting for (no surprise!) Laura herself, and for the way the other characters attempt to fix her identity in a way that accords with their assumptions about women. Hard-boiled or noir fiction famously tends to limit women to specific roles: victim, dame, femme fatale. Caspary and Laura are both aware of the way women get cast into roles that restrict their individuality and define them in relation to men; Laura’s resistance to this is one of the factors that puts her life in danger. “You are not dead,” another character says to her at one point; “you are a violent, living, bloodthirsty woman.” How much of that sentence is true? It depends, quite literally, on whose story you accept. In

In  To date, the books I’ve chosen for this seminar have all been by women writers, about women detectives, and explicitly interested in gender and detection. They all, that is, bring a lot of self-consciousness to their engagement with detective fiction as a genre. Collectively, they also cover a good range of subgenres or types of detective fiction. While in these respects the list has reasonable breadth, however, in other respects it is quite narrow; the feminist tradition it covers is, to put it mildly, not very intersectional. I put in some time in the past trying to fix this problem; though I came up short, the good news is that I do, as a result, already have a preliminary list of names to start with, particularly of African American authors: among these are

To date, the books I’ve chosen for this seminar have all been by women writers, about women detectives, and explicitly interested in gender and detection. They all, that is, bring a lot of self-consciousness to their engagement with detective fiction as a genre. Collectively, they also cover a good range of subgenres or types of detective fiction. While in these respects the list has reasonable breadth, however, in other respects it is quite narrow; the feminist tradition it covers is, to put it mildly, not very intersectional. I put in some time in the past trying to fix this problem; though I came up short, the good news is that I do, as a result, already have a preliminary list of names to start with, particularly of African American authors: among these are  So far I have never assigned a Canadian writer in either of my detective fiction classes, primarily because I haven’t found one that takes the genre in what seems like a new direction or that really made me sit up and take notice. (Phonse Jessome’s

So far I have never assigned a Canadian writer in either of my detective fiction classes, primarily because I haven’t found one that takes the genre in what seems like a new direction or that really made me sit up and take notice. (Phonse Jessome’s  One of the problems I ran into last time I went down this road was getting my hands on samples from the authors I was interested in. I probably just need to be more persistent and order a lot of titles through interlibrary loan. The other problem is that I’m not really a voracious or enthusiastic reader of mysteries (odd, I know, in the circumstances) so I tire easily of the necessary exploratory work and I can take a while to warm to books that are not immediately appealing to me (though I can eventually get there, as has happened with Walter Mosley’s Devil in a Blue Dress–still not a personal favorite, but one I have found very satisfying to teach). This is why I need help sifting through or coming up with good options so that I can make this reading list represent a wider range of voices. Ideas and recommendations would be very welcome.

One of the problems I ran into last time I went down this road was getting my hands on samples from the authors I was interested in. I probably just need to be more persistent and order a lot of titles through interlibrary loan. The other problem is that I’m not really a voracious or enthusiastic reader of mysteries (odd, I know, in the circumstances) so I tire easily of the necessary exploratory work and I can take a while to warm to books that are not immediately appealing to me (though I can eventually get there, as has happened with Walter Mosley’s Devil in a Blue Dress–still not a personal favorite, but one I have found very satisfying to teach). This is why I need help sifting through or coming up with good options so that I can make this reading list represent a wider range of voices. Ideas and recommendations would be very welcome.

Though I don’t dispute Hogeland’s interpretation, I did notice that she seems aware she’s working a bit hard to make the case. She attributes the challenge to Hughes’s subtlety: for instance,

Though I don’t dispute Hogeland’s interpretation, I did notice that she seems aware she’s working a bit hard to make the case. She attributes the challenge to Hughes’s subtlety: for instance,