Practically from our first meeting, she’d been after me to write a recovery journal. I told her I don’t write, I draw. She said this would be for myself only. I could share it, but only if I chose to do so. The idea being to get clarity and process some of my traumas. On that particular ball of yarn I didn’t know where to start. She suggested pinpointing where my struggles had started with substance abuse, abandonment, and so forth . . . I’ve made any number of false starts with this mess. You think you know where your own troubles lies, only to stare down the page and realize, no. Not there. It started earlier. Like these wars going back to George Washington and whiskey. Or in my case, chapter 1. First, I got myself born. The worst of the job was up to me. Here we are.

For a novel that has (more or less) exactly the same plot and (more or less) the same characters as David Copperfield, Demon Copperhead is remarkably unlike David Copperfield. This confused me a lot when I read the first half of Kingsolver’s novel back in January—confused and also alienated me, to the point that I not only put it aside unfinished but wrote plaintively to my book club asking if maybe we could choose something else for our next read. I’m glad now that other members said they were enjoying it and so we stayed the course: with our meeting to talk about it finally looming, I picked it up again yesterday and ended up reading right through to the end in a few hours. I was not delighted by it, but I became engrossed in it, and though overall I am still disappointed in it as a revision of Dickens’s novel, as its own novel Demon Copperhead is, I think, actually pretty good.

It is tempting but probably pointless to track through Demon Copperhead comparing its main ingredients to their counterparts in David Copperfield. On the other hand, some comparison is irresistible, if only to illustrate how Kingsolver both does and doesn’t do what Dickens does. “First, I got myself born,” her novel begins. Here, in contrast, is the famous opening of David Copperfield:

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show. To begin my life with the beginning of my life, I record that I was born (as I have been informed and believe) on a Friday, at twelve o’clock at night. It was remarked that the clock began to strike, and I began to cry, simultaneously.

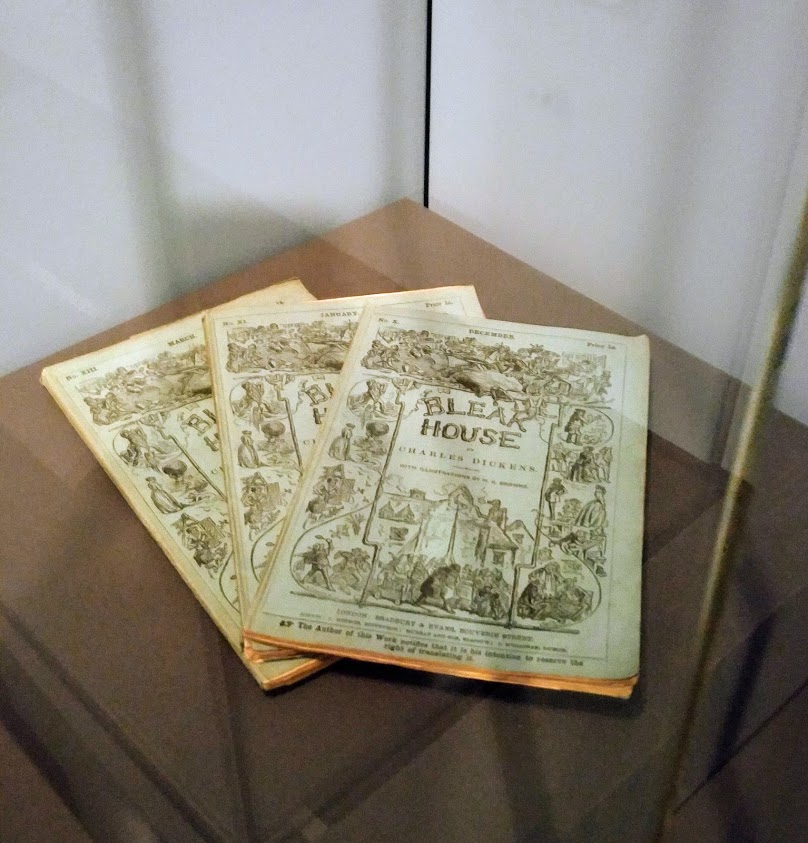

Kingsolver jumps right into the action, and really, it never stops, for the next 500+ pages. Demon Copperhead is a rush of narrative—a copious, colorful, fast-moving torrent of words. Although it is clear by the end of the novel that it is, like the original, retrospective, it has none of the layers of David Copperfield, which is complicated and enriched by foreshadowing and dramatic irony. It is perhaps surprising, given his reputation for exaggeration and hyperbole, that, on my reading anyway, Dickens is by far the more subtle and nuanced author of the two. Kingsolver (or, properly, her first-person protagonist Damon Fields) just keeps going and going and going, a kind of tireless Energizer Bunny of grim revelations about the hardships of life for a child born in poverty in Appalachia and growing up through the worst of the opioid crisis. At a time when the idea that fiction should have a purpose is (in elite circles, anyway) often dismissed as incompatible with real art, Demon Copperhead is, unapologetically, a fully committed ‘social problem’ novel: it has more in common, in that respect, with Mary Barton, or even with Bleak House, then with David Copperfield, which is, as its opening line tells us, a story about moral development—an individual story, a Bildungsroman. Its action is always, more than anything else, about David’s character, and especially about his tender, loving heart.

Kingsolver jumps right into the action, and really, it never stops, for the next 500+ pages. Demon Copperhead is a rush of narrative—a copious, colorful, fast-moving torrent of words. Although it is clear by the end of the novel that it is, like the original, retrospective, it has none of the layers of David Copperfield, which is complicated and enriched by foreshadowing and dramatic irony. It is perhaps surprising, given his reputation for exaggeration and hyperbole, that, on my reading anyway, Dickens is by far the more subtle and nuanced author of the two. Kingsolver (or, properly, her first-person protagonist Damon Fields) just keeps going and going and going, a kind of tireless Energizer Bunny of grim revelations about the hardships of life for a child born in poverty in Appalachia and growing up through the worst of the opioid crisis. At a time when the idea that fiction should have a purpose is (in elite circles, anyway) often dismissed as incompatible with real art, Demon Copperhead is, unapologetically, a fully committed ‘social problem’ novel: it has more in common, in that respect, with Mary Barton, or even with Bleak House, then with David Copperfield, which is, as its opening line tells us, a story about moral development—an individual story, a Bildungsroman. Its action is always, more than anything else, about David’s character, and especially about his tender, loving heart.

As novel about Appalachia and the opioid crisis, Demon Copperhead is quite compelling, although it is also pretty heavy-handed. (I might not have thought this about the novel if I hadn’t recently watched the excellent series Dopesick, which covers a lot of similar sociological territory and hits some of the same beats, in terms of storytelling.) What I figured out, when I returned to the novel after my long hiatus, is that the David Copperfield framing is a red herring, perhaps based on a misunderstanding or a misapplication of the kind of novel Dickens wrote. This point really clicked for me when I reached Kingsolver’s Acknowledgments, at the end of Demon Copperhead:

I’m grateful to Charles Dickens for writing David Copperfield, his impassioned critique of institutional poverty and its damaging effects on children in his society. Those problems are still with us. In adapting this novel to my own place and time, working for years with his outrage, inventiveness, and empathy at my elbow, I’ve come to think of him as my genius friend.

It’s notable to me that the rest of her acknowledgments are to people who helped with expertise related to social problems (“foster care and child protective services . . . logistics and desperations of addiction and recovery, Appalachian history” etc.) – not to Dickens or David Copperfield. It isn’t that David Copperfield is not about child poverty and harsh social conditions; it’s that (I would say, anyway) these circumstances are incidental in David Copperfield to David’s perceptions of his experiences, and to Dickens’s own preference for addressing material conditions as external manifestations of moral and imaginative conditions. At best, Kingsolver is taking Dickens more literally than is usually appropriate; at worst, she is entirely overlooking his preoccupation with David’s inner life.

It’s notable to me that the rest of her acknowledgments are to people who helped with expertise related to social problems (“foster care and child protective services . . . logistics and desperations of addiction and recovery, Appalachian history” etc.) – not to Dickens or David Copperfield. It isn’t that David Copperfield is not about child poverty and harsh social conditions; it’s that (I would say, anyway) these circumstances are incidental in David Copperfield to David’s perceptions of his experiences, and to Dickens’s own preference for addressing material conditions as external manifestations of moral and imaginative conditions. At best, Kingsolver is taking Dickens more literally than is usually appropriate; at worst, she is entirely overlooking his preoccupation with David’s inner life.

One of the costs of Kingsolver’s approach is prose that is also excessively literal, chock full of vivid, concrete details but leaving very little to—or providing very little stimulation for—our imaginations. Something I often discuss with my classes is the way Dickens’s writing itself creates in us, as we read it, the kind of mental activity he fears modern life is devaluing and suppressing: the flights of fancy in his language do for us, cultivate in us, what he fears we are losing. He writes in defiance of political economy, of utilitarianism, of facts—at least, of facts reduced to discrete and definitive units of measurement, the way they are in the famous opening of Hard Times:

‘Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!’

‘Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!’

Hard Times is Dickens’s most insistent and programmatic condemnation of sticking to “facts,” and also his most dogged but also (I think) rhetorically powerful defense of what he calls “fancy.” But he fights this fight in all of his novels in ways I have talked about here before, including in reference to David Copperfield, at least as much, if not more, through his style as through his explicit content.

I’m not saying Kingsolver’s prose is devoid of fancy. Most of its creative energy seems to me to rest in Damon’s voice, which is blunt and colloquial and observant, but not at all poetic. There is a lot of vivid imagery, although so much of it is in aid of things we’d rather not see that it can be hard to appreciate it as artistic. It’s the other qualities that, to my mind, define “Dickensian” writing that I really miss, though. For one thing, Kingsolver’s novel is entirely unleavened with humor. OK, our introduction to her version of Aunt Betsy and Mr. Dick (here, Damon’s grandmother Betsy Woodall and Brother Dick) is amusing, but oh, how I missed Janet and the donkeys! And though the basics of the plot about Uriah Heep’s malevolent machinations are the same, the exposure of U-Haul has none of the exuberant joy of Mr. Micawber’s increasingly vehement denunciations:

And last. I am now in a condition to show, by—HEEP’S—false books, and—HEEP’S—real memoranda, beginning with the partially destroyed pocket-book (which I was unable to comprehend, at the time of its accidental discovery by Mrs. Micawber, on our taking possession of our present abode, in the locker or bin devoted to the reception of the ashes calcined on our domestic hearth), that the weaknesses, the faults, the very virtues, the parental affections, and the sense of honour, of the unhappy Mr. W. have been for years acted on by, and warped to the base purposes of—HEEP. That Mr. W. has been for years deluded and plundered, in every conceivable manner, to the pecuniary aggrandisement of the avaricious, false, and grasping—HEEP.

Yes, he goes on like this for pages—and (as Joe Gargery would say), what larks!

What I missed most of all in Demon Copperhead was the melancholy tenderness that suffuses David Copperfield, and the way Dickens shades David’s highs and lows with his profound understanding of both the necessity and the heartbreak of losing our childhood innocence. The David that worships Steerforth and adores Dora is so loving and lovable: he is wrong, of course, in both cases, but Dickens is so good at making us feel to our core the cost of outgrowing mistakes like these, of becoming someone too savvy and knowing and suspicious to follow our hearts without question.

What I missed most of all in Demon Copperhead was the melancholy tenderness that suffuses David Copperfield, and the way Dickens shades David’s highs and lows with his profound understanding of both the necessity and the heartbreak of losing our childhood innocence. The David that worships Steerforth and adores Dora is so loving and lovable: he is wrong, of course, in both cases, but Dickens is so good at making us feel to our core the cost of outgrowing mistakes like these, of becoming someone too savvy and knowing and suspicious to follow our hearts without question.

There’s also just nothing in Demon Copperhead that rises to the level of Dickens’s sheer virtuosity as a writer in David Copperfield. The scene in which Kingsolver’s Steerforth (Fast Forward) comes to his end is dramatic and suspenseful but it has neither the rich pathos nor the glorious prose of Dickens’s chapter “The Tempest”:

The tremendous sea itself, when I could find sufficient pause to look at it, in the agitation of the blinding wind, the flying stones and sand, and the awful noise, confounded me. As the high watery walls came rolling in, and, at their highest, tumbled into surf, they looked as if the least would engulf the town. As the receding wave swept back with a hoarse roar, it seemed to scoop out deep caves in the beach, as if its purpose were to undermine the earth. When some white-headed billows thundered on, and dashed themselves to pieces before they reached the land, every fragment of the late whole seemed possessed by the full might of its wrath, rushing to be gathered to the composition of another monster. Undulating hills were changed to valleys, undulating valleys (with a solitary storm-bird sometimes skimming through them) were lifted up to hills; masses of water shivered and shook the beach with a booming sound; every shape tumultuously rolled on, as soon as made, to change its shape and place, and beat another shape and place away; the ideal shore on the horizon, with its towers and buildings, rose and fell; the clouds fell fast and thick; I seemed to see a rending and upheaving of all nature.

The ending of the chapter is in a different register altogether from the extravagance of that description: quieter, sadder, and resonant with everything that David has known and been and loved and lost:

As I sat beside the bed, when hope was abandoned and all was done, a fisherman, who had known me when Emily and I were children, and ever since, whispered my name at the door.

‘Sir,’ said he, with tears starting to his weather-beaten face, which, with his trembling lips, was ashy pale, ‘will you come over yonder?’

The old remembrance that had been recalled to me, was in his look. I asked him, terror-stricken, leaning on the arm he held out to support me:

‘Has a body come ashore?’

He said, ‘Yes.’

‘Do I know it?’ I asked then.

He answered nothing.

But he led me to the shore. And on that part of it where she and I had looked for shells, two children—on that part of it where some lighter fragments of the old boat, blown down last night, had been scattered by the wind—among the ruins of the home he had wronged—I saw him lying with his head upon his arm, as I had often seen him lie at school.

Honestly, it seems kind of unfair to point out that Kingsolver doesn’t—perhaps can’t—write like that. There’s a reason Dickens was called “the Inimitable!” No doubt, too, there are some of you who prefer what she does to what Dickens does. (To each their own, of course, but also, you’re just wrong!) To invite comparison with the greats is to set yourself up for failure, and I definitely wouldn’t say Demon Copperhead is a failure. I doubt I’ll read it again, though, whereas I am wholeheartedly looking forward to rereading David Copperfield again this fall with my students.

The

The

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

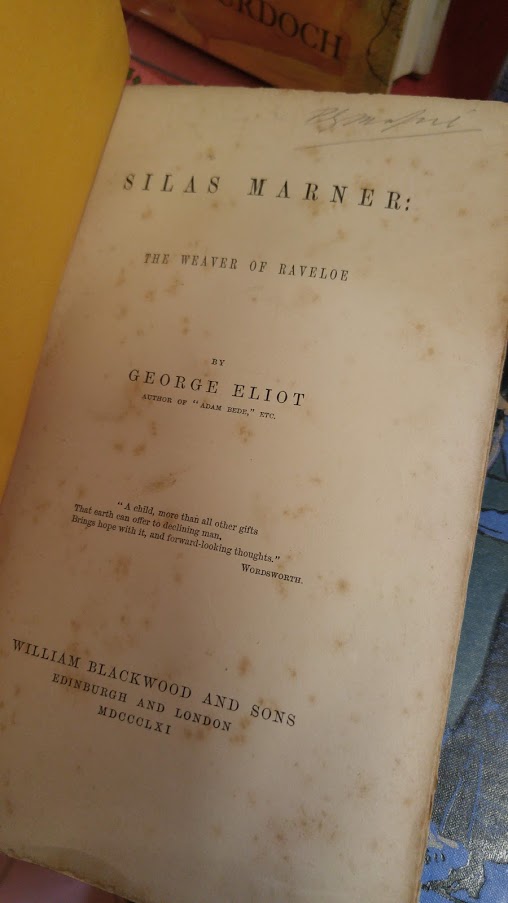

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon.

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon. Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

They had been married ten years, and until this present day on which Mr. Dombey sat jingling and jingling his heavy gold watch-chain in the great arm-chair by the side of the bed, had had no issue.

They had been married ten years, and until this present day on which Mr. Dombey sat jingling and jingling his heavy gold watch-chain in the great arm-chair by the side of the bed, had had no issue. That said, I think that if Dombey and Son were a better novel, I might have been fine on my own and not fallen, as I sadly did, into occasional fits of boredom, impatience, or irritation. Though obviously a first read is almost by definition an imperfect one, some books nonetheless make their greatness clear pretty promptly, and I didn’t think Dombey and Son ever did. It lacks the joyousness of David Copperfield: its children have all the pathos and none of the fun, its villains are more cardboard, its eccentrics are less quirky and more repetitive, its heroes and especially its heroine are much duller (imagine, a heroine who makes Agnes look subtle and complicated!). Though there is something impressive in the portrait of Mr. Dombey and the destructive vortex of his pride, Dickens does not take that critique and radiate it outward with anything like the breathtaking audacity of Bleak House, with its many variations on its central themes. The fairy tale quality of Florence’s story, with its long emotional exile as she is, so paradoxically, held captive by her father’s neglect, loses a lot of its impact as it drags on with its one repetitive idea: Louisa Gradgrind’s story has some of the same qualities but is so much more intense, and also so much more interesting because, unlike Florence, Louisa is capable of anger.

That said, I think that if Dombey and Son were a better novel, I might have been fine on my own and not fallen, as I sadly did, into occasional fits of boredom, impatience, or irritation. Though obviously a first read is almost by definition an imperfect one, some books nonetheless make their greatness clear pretty promptly, and I didn’t think Dombey and Son ever did. It lacks the joyousness of David Copperfield: its children have all the pathos and none of the fun, its villains are more cardboard, its eccentrics are less quirky and more repetitive, its heroes and especially its heroine are much duller (imagine, a heroine who makes Agnes look subtle and complicated!). Though there is something impressive in the portrait of Mr. Dombey and the destructive vortex of his pride, Dickens does not take that critique and radiate it outward with anything like the breathtaking audacity of Bleak House, with its many variations on its central themes. The fairy tale quality of Florence’s story, with its long emotional exile as she is, so paradoxically, held captive by her father’s neglect, loses a lot of its impact as it drags on with its one repetitive idea: Louisa Gradgrind’s story has some of the same qualities but is so much more intense, and also so much more interesting because, unlike Florence, Louisa is capable of anger. And so it went for me, really, throughout Dombey and Son: it kept reminding me of other Dickens novels but the comparison was never in its favor. I flagged a lot of bits I liked, and over its 900+ pages there were certainly moments I found sad or funny or even great in that way that only Dickens can be great. I was pretty fond of Captain Cuttle by the end! But at the same time, overall it felt cluttered and it took (yes) a bit too long to get us to the one result that really mattered, namely Mr. Dombey’s realization that his daughter was always already the child he needed. In Novels of the Eighteen-Forties Kathleen Tillotson notes that “Dombey and Son stands out from among Dickens’s novels as the earliest example of responsible and successful planning; it has unity not only of action, but of design and feeling.” I suppose, then, that you could consider it practice for the masterpieces that would follow, a lesser but valuable trial run. I can’t imagine choosing it as a teaching text over any of the ones I usually assign.

And so it went for me, really, throughout Dombey and Son: it kept reminding me of other Dickens novels but the comparison was never in its favor. I flagged a lot of bits I liked, and over its 900+ pages there were certainly moments I found sad or funny or even great in that way that only Dickens can be great. I was pretty fond of Captain Cuttle by the end! But at the same time, overall it felt cluttered and it took (yes) a bit too long to get us to the one result that really mattered, namely Mr. Dombey’s realization that his daughter was always already the child he needed. In Novels of the Eighteen-Forties Kathleen Tillotson notes that “Dombey and Son stands out from among Dickens’s novels as the earliest example of responsible and successful planning; it has unity not only of action, but of design and feeling.” I suppose, then, that you could consider it practice for the masterpieces that would follow, a lesser but valuable trial run. I can’t imagine choosing it as a teaching text over any of the ones I usually assign. When I taught David Copperfield in the fall, I addressed its length explicitly (the OUP edition is 944 pages). I always talk about length when teaching Middlemarch. “I don’t see how the sort of thing I want to do could have been done briefly,” Eliot wrote: that’s a good starting point for discussion about what exactly she is doing and how those purposes make the novel’s scale an important element of its form. (Interestingly, at least in the OUP edition Middlemarch, at 904 pages, is shorter than any of these Dickens novels, though I don’t know if the font size or page layout is standard. It reads longer, I think, perhaps because it demands scrupulous attention in a way that Dickens’s exuberant excesses may not appear to.) With Bleak House, we usually tie the novel’s multiplicities to the scale of its critique: it isn’t about one house or one family or one sad crossing sweeper but about a whole society.

When I taught David Copperfield in the fall, I addressed its length explicitly (the OUP edition is 944 pages). I always talk about length when teaching Middlemarch. “I don’t see how the sort of thing I want to do could have been done briefly,” Eliot wrote: that’s a good starting point for discussion about what exactly she is doing and how those purposes make the novel’s scale an important element of its form. (Interestingly, at least in the OUP edition Middlemarch, at 904 pages, is shorter than any of these Dickens novels, though I don’t know if the font size or page layout is standard. It reads longer, I think, perhaps because it demands scrupulous attention in a way that Dickens’s exuberant excesses may not appear to.) With Bleak House, we usually tie the novel’s multiplicities to the scale of its critique: it isn’t about one house or one family or one sad crossing sweeper but about a whole society. With David Copperfield, though, I found myself wanting to add another consideration, which is the particular ways Dickens makes his novels so long–when he does, because of course he doesn’t always, which is another reason to think about their length as meaningful rather than haphazard or (as those who object to Dickens’s novels as “too long” seem to imply) artistically lazy or inept. A lot of the length in Dickens’s fiction comes from what we might call “riffing.” (Merriam-Webster defines “riff” as “

With David Copperfield, though, I found myself wanting to add another consideration, which is the particular ways Dickens makes his novels so long–when he does, because of course he doesn’t always, which is another reason to think about their length as meaningful rather than haphazard or (as those who object to Dickens’s novels as “too long” seem to imply) artistically lazy or inept. A lot of the length in Dickens’s fiction comes from what we might call “riffing.” (Merriam-Webster defines “riff” as “

The other novel I’ve been working on for class is Valdez Is Coming. It is a pretty different reading experience in almost every way, but it too turns on questions about what’s right and what’s fair, and about when and where to draw the line in the face of an injustice. “Why do you bother?” Valdez is asked about his quest to get restitution for a widow whose fate nobody else cares about because she’s Apache and her dead husband (though shot by Valdez himself) was the victim of their unrepentant racism. “If I tell you what I think,” he replies, “it doesn’t sound right. It’s something I know.” By that time we know too why standing up to the men who mocked him, shot at him, then crucified him when he asked for justice is something he has to do. It’s about not letting them win, yes, but that outcome matters because of who they are, and who he is — and, if we’re on his side, who we want to be, and how we want the world to be. “You get one time, mister, to prove who you are” he tells his antagonist during their final showdown. Valdez (true to his genre) proves who he is through action, including a lot of violence. (I wouldn’t like this novel as much as I do if this violence were treated differently — simply as action, for instance, or drama — but Leonard imbues it with

The other novel I’ve been working on for class is Valdez Is Coming. It is a pretty different reading experience in almost every way, but it too turns on questions about what’s right and what’s fair, and about when and where to draw the line in the face of an injustice. “Why do you bother?” Valdez is asked about his quest to get restitution for a widow whose fate nobody else cares about because she’s Apache and her dead husband (though shot by Valdez himself) was the victim of their unrepentant racism. “If I tell you what I think,” he replies, “it doesn’t sound right. It’s something I know.” By that time we know too why standing up to the men who mocked him, shot at him, then crucified him when he asked for justice is something he has to do. It’s about not letting them win, yes, but that outcome matters because of who they are, and who he is — and, if we’re on his side, who we want to be, and how we want the world to be. “You get one time, mister, to prove who you are” he tells his antagonist during their final showdown. Valdez (true to his genre) proves who he is through action, including a lot of violence. (I wouldn’t like this novel as much as I do if this violence were treated differently — simply as action, for instance, or drama — but Leonard imbues it with  The past couple of weeks have felt pretty hectic to me, mostly because any time you teach a new course, or just new material, you have to build up all its materials from scratch. This term it’s Pulp Fiction that needs, well, everything! Not only do I not have any lecture notes to draw on for most of the readings (but boy, am I looking forward to our weeks on The Maltese Falcon, which I

The past couple of weeks have felt pretty hectic to me, mostly because any time you teach a new course, or just new material, you have to build up all its materials from scratch. This term it’s Pulp Fiction that needs, well, everything! Not only do I not have any lecture notes to draw on for most of the readings (but boy, am I looking forward to our weeks on The Maltese Falcon, which I  In 19th-Century Fiction we are nearly through Bleak House. They seem to be hanging in there! In this class too I have felt myself falling into too much lecturing, but I have been consciously working on balancing that out with some much more open-ended sessions. I feel as if lecturing in a more orderly way can be an important part of our work on a novel as long and complex as Bleak House, where a risk for newcomers to the novel is getting overwhelmed by minutiae: I try in my lecture segments to give them big grids or maps on which they can later place specific characters or incidents as they arise, or rise to prominence. I also try to plant interpretive seeds in the form of questions to be followed up on as they read further. That way, when we do approach topics through discussion, they will already have been thinking about some of them on their own — which usually seems to work!

In 19th-Century Fiction we are nearly through Bleak House. They seem to be hanging in there! In this class too I have felt myself falling into too much lecturing, but I have been consciously working on balancing that out with some much more open-ended sessions. I feel as if lecturing in a more orderly way can be an important part of our work on a novel as long and complex as Bleak House, where a risk for newcomers to the novel is getting overwhelmed by minutiae: I try in my lecture segments to give them big grids or maps on which they can later place specific characters or incidents as they arise, or rise to prominence. I also try to plant interpretive seeds in the form of questions to be followed up on as they read further. That way, when we do approach topics through discussion, they will already have been thinking about some of them on their own — which usually seems to work!

In 19th-Century Fiction we’ve finished our first two novels, Villette and Great Expectations. Although Villette is a fascinating novel, I had more fun (rather to my surprise) rereading Great Expectations. I’ve read and taught it so often that my own expectations were kind of low as we started it up, but I fell right into it, especially the climactic confrontation between Pip, Estella, and Miss Havisham after Pip’s world has been up-ended:

In 19th-Century Fiction we’ve finished our first two novels, Villette and Great Expectations. Although Villette is a fascinating novel, I had more fun (rather to my surprise) rereading Great Expectations. I’ve read and taught it so often that my own expectations were kind of low as we started it up, but I fell right into it, especially the climactic confrontation between Pip, Estella, and Miss Havisham after Pip’s world has been up-ended:

In Mystery and Detective Fiction we’ve wrapped up not only The Moonstone but Sherlock Holmes and a sampler of other great detectives as well (we read one story each by G. K Chesterton, R. Austen Freeman, and Jacques Futrelle). Today we started our discussion of Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. I enjoy using Christie to spark discussion about canonicity: I point out that despite being possibly the best-selling novelist of all time, she has no literary standing compared to her contemporaries Henry James, Virginia Woolf or James Joyce, which gives me a chance to suggest that modernism set a lot of the terms for discussions of literary merit that we now often take for granted. This means talking about things like linguistic or syntactical difficulty, which on the face of it, Christie is having none of: her prose is remarkably lucid. Next time, though, when all is known, we’ll go over just how tricky she actually is — telling us everything while keeping everything from us. Is this its own kind of difficulty, or is it just trickery, and if so, is that somehow a lower order of skill? To some extent I am playing devil’s advocate in asking why she should be taken any less seriously than Woolf: for me, conversation about Christie flags pretty quickly once the game is played out, and for my money there are other mystery novelists who are a lot more interesting to think about. But she’s excellent of her kind, and I think it’s worth provoking a conversation about whether it makes sense to value some kinds more than others. This is the “genre fiction” version of the YA debates, of course.

In Mystery and Detective Fiction we’ve wrapped up not only The Moonstone but Sherlock Holmes and a sampler of other great detectives as well (we read one story each by G. K Chesterton, R. Austen Freeman, and Jacques Futrelle). Today we started our discussion of Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. I enjoy using Christie to spark discussion about canonicity: I point out that despite being possibly the best-selling novelist of all time, she has no literary standing compared to her contemporaries Henry James, Virginia Woolf or James Joyce, which gives me a chance to suggest that modernism set a lot of the terms for discussions of literary merit that we now often take for granted. This means talking about things like linguistic or syntactical difficulty, which on the face of it, Christie is having none of: her prose is remarkably lucid. Next time, though, when all is known, we’ll go over just how tricky she actually is — telling us everything while keeping everything from us. Is this its own kind of difficulty, or is it just trickery, and if so, is that somehow a lower order of skill? To some extent I am playing devil’s advocate in asking why she should be taken any less seriously than Woolf: for me, conversation about Christie flags pretty quickly once the game is played out, and for my money there are other mystery novelists who are a lot more interesting to think about. But she’s excellent of her kind, and I think it’s worth provoking a conversation about whether it makes sense to value some kinds more than others. This is the “genre fiction” version of the YA debates, of course.