The publication of Menewood, the long-awaited sequel to Hild, made this seem like a good time to re-run this earlier post on Griffith’s wonderful novel.

The publication of Menewood, the long-awaited sequel to Hild, made this seem like a good time to re-run this earlier post on Griffith’s wonderful novel.

I found Hild shelved in the Fantasy and Science Fiction section at Bookmark, which means I almost didn’t realize they had it in stock, as I don’t usually browse that section. (I was poking around in case they had John Crowley’s Little, Big, which Tom had got me interested in.) I can see why the staff had put it there: the front cover blurb compares it to The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones. But it isn’t fantasy: it’s historical fiction, if based, Griffith says in her Author’s Note, on a particularly scanty record: “We have no idea what [Hild] looked like, what she was good at, whether she married or had children.” “But clearly,” Griffith goes on, “she was extraordinary,” and that’s certainly true of the protagonist Griffith has created from the sparse materials available.

Maybe, though, considering Hild “fantasy” is not altogether a category mistake. “I made it up,” Griffith says about her story, while explaining that it is also deeply researched: “I learnt what I could of the late sixth and early seventh centuries: ethnography, archaeology, poetry, numismatics, jewellery, textiles, languages, food production, weapons, and more. And then I re-created that world . . . ” — that is, she engaged in “worldbuilding,” which is a fundamental (perhaps the fundamental?) task of the fantasy or science fiction author. Of course, her world is built out of real pieces, but it’s an artificial construction nonetheless. I suppose this could be said of any historical fiction, or any fiction at all, so maybe I’m trying to blur a line that’s already indistinct. But there’s something about Hild — the strangeness of its world, but also of Griffith’s evocation of it — that makes it haunting and uncanny, as if we are not so much in an earlier version of our own world but in an alternative version.

It’s mostly Hild herself who’s responsible for that sense that we’re looking through, rather than at, the world: she is the king’s “seer,” the “light of the world,” and thus it is her job, her destiny, her “wyrd” or fate, to perceive the world differently than others. She is constantly seeking patterns, in nature and in the shifting relationships of the court and the kingdom. Her powers of perception set her apart: she is admired, revered, and feared. Her gifts are not necessarily supernatural, though: her “visions” are the results of long thought and sharp intelligence, and sometimes they are also simply predictions shaped to suit what her listeners (especially the King) want most to hear or do. Signs and omens must be interpreted, and that too requires political savvy and deft diplomacy more than any preternatural insight. Hild’s status as the King’s “light” defines her from birth and shapes both how she is treated and how she must behave: it is a burden, a responsibility, a terrible risk and a great liberation, because it exempts her from the ordinary constraints of a woman’s life.

Hild is an extraordinary character: strong, charismatic, intelligent, intensely physical, remarkably whole and convincing. One of the most interesting aspects of her characterization is the novel’s certainty about her woman’s body: it’s a central fact of her life and Griffith makes that clear without apology, voyeurism, or special pleading. I can’t think, for instance, of another novel in which starting to menstruate is a plot point in quite the way it is here — incorporated with perfect naturalness into the ongoing story of the heroine’s physical and psychological maturation, experienced as an initiation into an alliance of other women, associated with independence from authority rather than readiness for male sexual attention. That’s not to say that sexuality isn’t also an important part of Hild’s story, but though there is a love story of sorts running through the novel, her desires are hers, physical feelings she can satisfy on her own, or with women: they are not (or not just) ties that bind her emotionally to a man, and they certainly do not define her ambitions or determine the arc of her story.

The shape of that story is only partially revealed by the end of Hild. (Griffith is working on the sequel now, but I almost wish she’d waited and published one epic novel, as Hild so obviously stops rather than concludes.) Hild eventually becomes Saint Hilda of Whitby, but she isn’t there when we leave her this time. What we have seen to this point, though, is her development from an uncanny child into a fierce woman. The overall trajectory of Hild is all upward in that way: not just Hild herself, but the world she lives in is taking on a different form over the novel. The most important change is the rise of Christianity, which is gradually replacing the old forms of worship which Hild, as a seer, initially represents and serves. The transition is an uneven and not entirely welcome one. For one thing, people are reluctant to give up their old beliefs, and the representatives of the new God are not altogether persuasive. The God they represent, too, is very different from the old gods, who were more personal and more fun. “They don’t like jokes,” says one of Hild’s women about the Christians; “I don’t think their god does either.” And the new God is demanding in unfamiliar ways, insisting on obedience and reverence, and preoccupied with the unfamiliar notion of original sin. He’s also “squeamish,” inexplicably hostile to women’s bodies: “No blood in the church. No woman with her monthly bleeding. It makes no sense,” says Hild’s friend.

Will this new God diminish or invalidate Hild’s power, as a seer or as a woman? Will He punish her, perhaps, for the evils she has committed as a warrior or a prophet of other gods? Hild approaches her own baptism with trepidation, but then feels renewed courage:

She breathed deep. She was Anglisc. She would not burn. She would endure and hold true to her oath. An oath, a bond. A truth, a guide, a promise. To three gods in one. To the pattern. For even gods were part of the pattern, even three-part gods. The pattern was in everything. Of everything. Over everything. . . .

Her heart beat with it, her tears fell with it, her spirit soared with it. Here, now, they were building a great pattern, she could feel it, and she would trace its shape one day: that was her wyrd, and fate goes as ever it must. Today she was swearing to it, swearing here, with her people.

I wondered (given that she becomes a Christian saint) whether Hild’s baptism would stand as an epiphanic moment of faith — as a revelation. While the language and the mood here is uplifted, though, the strongest sense is one of continuity: “she was still herself,” the scene concludes. Christianity never seems to be the one right way: it’s just another way, and one that is as prone as the old ways to express the will, greed, and ambition of its adherents rather than any divine plan. Hild’s strength continues to be herself — her limbs, trained for fighting, and her mind, astute and endlessly observing.

The other thing that’s rising in the world of the novel is literacy. This is tied to Christianity, in that it’s the priests who are usually the most ‘lettered’ of the characters. But Hild quickly perceives the value of writing as a way of maintaining networks across distances. Her ability to read and write is valuable to her politically, as her success and survival as a seer depends on good and abundant information. But it means most to her personally, as the typical fate of women is to be sent far from home and family in their roles as “peaceweavers,” cementing alliances as wives then securing kingdoms with their heirs. Hild realizes that if she could write, for instance, to her married sister Hereswith, Hereswith “wouldn’t be lost to her”: for someone in Hild’s anomalous and therefore lonely position, letters would be a lifeline, bringing her news and also preserving her own private identity while living among those to whom she is “the maid who killed, the maid who felt nothing. The maid with no mother or sister or friend.”

The novelist Griffith most reminds me of is Dorothy Dunnett. She luxuriates in tactile details the way Dunnett does, for one thing, as in this description of a waterfront marketplace:

The novelist Griffith most reminds me of is Dorothy Dunnett. She luxuriates in tactile details the way Dunnett does, for one thing, as in this description of a waterfront marketplace:

Rhenish glass: cups and bowls and flasks. Wheel-thrown pottery, painted in every colour and pattern. Cloth. Swords — swords for sale — and armor. Jewels, with stones Hild had never seen, including great square diamonds, as grey as a Blodmonath sky. Perfume in tiny stoppered jars, and next to them even smaller jars — one the size of Hild’s fingernail — sealed with wax: poison. . . . A six-stringed lyre inlaid with walnut and copper, and the beaver-skin bag to go with it. A set of four nested silver bowls from Byzantium, chased and engraved with lettering that Fursey, peering over her shoulder, said was Greek. But Hild barely heard him: Somewhere a man was calling in a peculiar cadence, and he sounded almost Anglisc. Almost. Instead of the rounded thump of Anglisc, these oddly shaped words rolled just a little wrong. Not apples, she thought. Pears. Heavy at the bottom, longer on the top.

The extraordinary complexity of the created world is also reminiscent of Dunnett — the intricate family trees, the tangled web of alliances, the unfamiliarity of the names and vocabulary, and thus the associated down side of such authorial mastery: our (or at any rate, my) difficulty keeping track of who’s who, of who’s doing what to whom and why. Like King Hereafter, for example, Hild is full of passages that perplex rather than clarify the action:

As the weather improved, messages began to come in from all over the isle. Two, from Rheged and from Alt Clut, said the same thing: Eochaid Buide of the Dál Riate was sending an army to aid the Cenél Cruithen against Fiachnae mach Demmáin of the Dál Fiatach, and chief among the Dál Riatan war band were the Idings — though the man from Rheged thought two, Oswald and Osric, called the Burnt, while the messenger from Alt Clut thought three, Oswald, Osric the Burnt, and young Osbald.

Or how about this one;

The murdered Eorpwald had been the godson of Edwin. Sigebert was of a different Christian lineage. he had spent his time across the narrow sea at the Frankish court of Clothar, and now Dagobert. If Sigebert was bringing threescore men, they would be Dagobert’s. If he won with their help, he would be obliged to align himself with the Franks. What would that mean for Edwin? Where was Dagobert in relation to the growing alliances of the middle country and the west — Penda and Cadwallon — and the men of the north: Idings, Picts, Scots of Dál Riata, Alt Clut, perhaps Rheghed?

Where was Dagobert, indeed? It helped a bit when I found a partial guide to pronunciation in the back of the book, and a glossary, and there’s a family tree too, but my experience reading Dunnett helped the most, particularly my conclusion that I don’t need to keep up with all the details to stay interested. Both authors are good enough story tellers that the necessary drama rises above the morass of confusing specifics. If I didn’t always know exactly why Hild was fighting someone in particular, it was enough to know that she had her reasons: the heat and blood of the battle was no less intense because I had to suspend, not disbelief, but my desire for perfect comprehension. The absolutely key characters — her mother Breguswith, her best friend, sparring partner, half-brother, and eventual husband Cian, or her “gemaecce” (“female partner”) Begu, for instance — are wholly distinct, and above it all is always Hild herself, “the pattern-making mind of the world.”

As you might expect, I am very much looking forward to reading Menewood!

This post was first published on May 31, 2015.

Like Elena Knows, A Little Luck is a small book that packs a powerful punch. Now that the first impact of reading it has passed, I do find myself wondering: did it earn its effect? Is that even a fair question? But Elena Knows is

Like Elena Knows, A Little Luck is a small book that packs a powerful punch. Now that the first impact of reading it has passed, I do find myself wondering: did it earn its effect? Is that even a fair question? But Elena Knows is  I’ve always loved these lines from Tennyson’s The Princess:

I’ve always loved these lines from Tennyson’s The Princess: Actually, thinking about it now, maybe there are more moving parts than there used to be. Once upon a time we didn’t use an LMS, for example, and while there’s no doubt that Brightspace (formerly Blackboard formerly Web CT formerly DIY websites) is a useful back-up system for in-person courses—a storage facility available to your students 24/7 so they can never not locate their syllabus!—it’s also the case that expectations have gone up considerably around our use of them (and students’ reliance on them). Now I post my PPT slides on Brightspace after class, for example, something that requires multiple additional steps, assuming I remember to do it in the first place. (I never used to use PowerPoint, either, and I blame it and Brightspace, which both require incessant mousing, for my now chronic shoulder pain.) I used to give quizzes and midterms in class; now, they are all taken in Brightspace—but that too means many more steps than devising the questions and making copies, setting up all the many features just right and entering the questions in the optimal way. When we were all online, I posted weekly announcements for my classes: it turns out students really appreciated these, so I’ve kept doing them, but they take me (no kidding) hours to compose, both to make sure they are optimally clear and useful and because heaven forbid there’s a mistake in one, like a wrong deadline, that gets fixed in their minds or calendars in spite of any subsequent efforts to correct it! Recently, too, in a departmental discussion around class size and workload, one of my colleagues pointed out ruefully that “there didn’t used to be email” and that is such a good point, especially as our class sizes have gone up even as we became not just teachers but customer service representatives! (And yet somehow, without an LMS and without Outlook and without PowerPoint, we managed to do our jobs. Imagine that. Did we do a worse job? Maybe in some respects—accessibility seems like a key point here—but I really do wonder how much all of this apparatus actually helps, rather than hinders, us in our core mission.)

Actually, thinking about it now, maybe there are more moving parts than there used to be. Once upon a time we didn’t use an LMS, for example, and while there’s no doubt that Brightspace (formerly Blackboard formerly Web CT formerly DIY websites) is a useful back-up system for in-person courses—a storage facility available to your students 24/7 so they can never not locate their syllabus!—it’s also the case that expectations have gone up considerably around our use of them (and students’ reliance on them). Now I post my PPT slides on Brightspace after class, for example, something that requires multiple additional steps, assuming I remember to do it in the first place. (I never used to use PowerPoint, either, and I blame it and Brightspace, which both require incessant mousing, for my now chronic shoulder pain.) I used to give quizzes and midterms in class; now, they are all taken in Brightspace—but that too means many more steps than devising the questions and making copies, setting up all the many features just right and entering the questions in the optimal way. When we were all online, I posted weekly announcements for my classes: it turns out students really appreciated these, so I’ve kept doing them, but they take me (no kidding) hours to compose, both to make sure they are optimally clear and useful and because heaven forbid there’s a mistake in one, like a wrong deadline, that gets fixed in their minds or calendars in spite of any subsequent efforts to correct it! Recently, too, in a departmental discussion around class size and workload, one of my colleagues pointed out ruefully that “there didn’t used to be email” and that is such a good point, especially as our class sizes have gone up even as we became not just teachers but customer service representatives! (And yet somehow, without an LMS and without Outlook and without PowerPoint, we managed to do our jobs. Imagine that. Did we do a worse job? Maybe in some respects—accessibility seems like a key point here—but I really do wonder how much all of this apparatus actually helps, rather than hinders, us in our core mission.) How are things going otherwise in my classes? So far 19th-Century Fiction seems great (I hope it’s not just me who thinks so!). It’s the Austen to Dickens version this term, and I took the risk of assigning Pride and Prejudice, which as regular readers will know

How are things going otherwise in my classes? So far 19th-Century Fiction seems great (I hope it’s not just me who thinks so!). It’s the Austen to Dickens version this term, and I took the risk of assigning Pride and Prejudice, which as regular readers will know  My other class this term is a section of intro, once again the prosaically-named “Literature: How It Works.” But this time it’s in person, because I was so disheartened by the end of

My other class this term is a section of intro, once again the prosaically-named “Literature: How It Works.” But this time it’s in person, because I was so disheartened by the end of

It used to be a ritual for me to post a recap of

It used to be a ritual for me to post a recap of

Like everyone else I know, I was really impressed by Elena Knows; it was a treat to find that Piniero’s

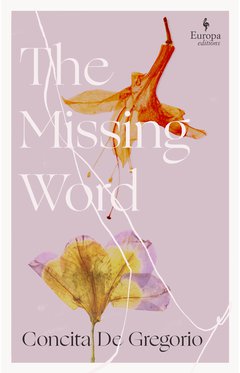

Like everyone else I know, I was really impressed by Elena Knows; it was a treat to find that Piniero’s  Devotion or Semi-Detached (or, in parts, North Woods)—that otherwise deal in wholly human or natural problems. De Gregorio doesn’t resort to wish-fulfillment or fantasy and that is both the pain and the strength of her treatment of love and loss.

Devotion or Semi-Detached (or, in parts, North Woods)—that otherwise deal in wholly human or natural problems. De Gregorio doesn’t resort to wish-fulfillment or fantasy and that is both the pain and the strength of her treatment of love and loss. My last two reads of this summer were Yiyun Li’s The Book of Goose and Ann Patchett’s Tom Lake. For me, one was a hit, the other a miss.

My last two reads of this summer were Yiyun Li’s The Book of Goose and Ann Patchett’s Tom Lake. For me, one was a hit, the other a miss. Another warning sign should have been how many reviews (including some quoted in the pages of “Praise for The Book of Goose” that lead off my paperback edition) compare it to Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. I am cynical about these tendentious excerpts so I don’t pay very close attention to them when I’m making up my mind about what to read. Maybe I should change my habits! Because the Ferrante comparison occurred to me not too far into Li’s novel, and not for good reasons. (

Another warning sign should have been how many reviews (including some quoted in the pages of “Praise for The Book of Goose” that lead off my paperback edition) compare it to Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. I am cynical about these tendentious excerpts so I don’t pay very close attention to them when I’m making up my mind about what to read. Maybe I should change my habits! Because the Ferrante comparison occurred to me not too far into Li’s novel, and not for good reasons. ( Tom Lake was a much more enjoyable read, although like the other Patchett novels I have read recently, it didn’t seem to me to go particularly deep. Still, there was something really satisfying about it: I liked it a lot more than either

Tom Lake was a much more enjoyable read, although like the other Patchett novels I have read recently, it didn’t seem to me to go particularly deep. Still, there was something really satisfying about it: I liked it a lot more than either  I was raised with the kind of faith that does not doubt. God had been as much a part of me as my own marrow, and when I discovered my bones to be empty, fluting music discordant to anything I had sung in church, my anguish was real . . . The understanding I have now, that the world spins on a deeper mystery than anything that might be set into language, was not with me then. Now I know that my mind is too small to hold the spirit. The spirit, I hope, holds me.

I was raised with the kind of faith that does not doubt. God had been as much a part of me as my own marrow, and when I discovered my bones to be empty, fluting music discordant to anything I had sung in church, my anguish was real . . . The understanding I have now, that the world spins on a deeper mystery than anything that might be set into language, was not with me then. Now I know that my mind is too small to hold the spirit. The spirit, I hope, holds me. If you’re a friend of mine on social media, it won’t surprise you that Hernan Diaz’s Trust is the first one. It is an inarguably ingenious novel, but I thought (and the other members of my book club agreed) that the payoff for its ingenuity in the second half wasn’t enough to make up for the extraordinary, if self-conscious, dullness of the first half. Even a novel that can only really light up on a second reading can (and, arguably, should) generate some excitement the first time through. For me, a case in point would be

If you’re a friend of mine on social media, it won’t surprise you that Hernan Diaz’s Trust is the first one. It is an inarguably ingenious novel, but I thought (and the other members of my book club agreed) that the payoff for its ingenuity in the second half wasn’t enough to make up for the extraordinary, if self-conscious, dullness of the first half. Even a novel that can only really light up on a second reading can (and, arguably, should) generate some excitement the first time through. For me, a case in point would be  I picked up Daniel Mason’s The Winter Soldier because I’m writing up his latest novel, North Woods, for the TLS and it’s good enough that I wanted to read more by him. The Winter Soldier is quite unlike North Woods, mostly in ways that favor the newer novel—which suggests Mason is getting better at his craft! The Winter Soldier (2018) is a good old-fashioned historical novel. It is packed with concrete details that make the time and place of its action vivid in the way I want historical fiction to be vivid. It takes place mostly in a remote field hospital in the Carpathian mountains during WWI; its protagonist, Lucius Krzelewski, is a medical student rapidly converted to a doctor to serve the desperate needs of the Austro-Hungarian army. His time at the hospital is full of harrowing incidents; through them runs his growing interest in an illness that eludes physical diagnosis and treatment—what today we would call PTSD. There are chaotic battle scenes and idyllic interludes; there’s a love story as well. It’s good! It really immerses you in its world, and (unlike Trust!) makes you care about its characters. I ended it not really sure it was about anything more than that. Novels don’t need to be, of course, though the best ones are. Still, I liked it enough that I will probably also look up Mason’s other novels, starting with The Piano Tuner. North Woods is a lot smarter and more subtle, though. (I am not sure it’s entirely successful: in my review, I will say more about that, when I figure out how to!)

I picked up Daniel Mason’s The Winter Soldier because I’m writing up his latest novel, North Woods, for the TLS and it’s good enough that I wanted to read more by him. The Winter Soldier is quite unlike North Woods, mostly in ways that favor the newer novel—which suggests Mason is getting better at his craft! The Winter Soldier (2018) is a good old-fashioned historical novel. It is packed with concrete details that make the time and place of its action vivid in the way I want historical fiction to be vivid. It takes place mostly in a remote field hospital in the Carpathian mountains during WWI; its protagonist, Lucius Krzelewski, is a medical student rapidly converted to a doctor to serve the desperate needs of the Austro-Hungarian army. His time at the hospital is full of harrowing incidents; through them runs his growing interest in an illness that eludes physical diagnosis and treatment—what today we would call PTSD. There are chaotic battle scenes and idyllic interludes; there’s a love story as well. It’s good! It really immerses you in its world, and (unlike Trust!) makes you care about its characters. I ended it not really sure it was about anything more than that. Novels don’t need to be, of course, though the best ones are. Still, I liked it enough that I will probably also look up Mason’s other novels, starting with The Piano Tuner. North Woods is a lot smarter and more subtle, though. (I am not sure it’s entirely successful: in my review, I will say more about that, when I figure out how to!) And then there’s Claudia Piñeiro’s Betty Boo, which I found a really satisfying combination of smart plotting, thoughtful storytelling, and ideas that matter. In some ways it is less ambitious than the other two novels: it is structured more or less conventionally as a crime novel, and there aren’t really any narrative tricks to it, unless you count the sections that are ostensibly written by the protagonist, Nurit Iscar, about its central murder case. Iscar is a crime novelist who has had a professional setback (a crushing review of her foray into romantic fiction) and is currently getting by as a ghost writer. A contact at a major newspaper asks her to write some articles about a murder from a less journalistic and more contemplative perspective; in aid of this mission, she moves into the gated community where the victim lived and died. She ends up collaborating with the reporters on the crime beat as they investigate the death and discover that it is a part of a larger and more sinister operation—about which, of course, I will not give you any details here! Betty Boo is an unusual book: it doesn’t read quite like a “genre” mystery, as it is at least as interested in Nurit’s life and especially her relationships, with her close women friends and her lovers, as it is in its crime story. Also, Betty Boo is about crime, reporting, and fiction as themes, though its attention to these issues is integrated into the storytelling so that it never really feels metafictional—unlike Trust, which is all gimmick and so no substance, Betty Boo seems committed to the value and possibility of substance, even as Piñeiro provokes us to think about the obstacles we face in achieving it, in writing or in life, especially now that the news as a vehicle for both information and storytelling has become so degraded. I appreciated how original Betty Boo felt, and how genuinely interesting it was: I haven’t read another writer who does quite what Piñeiro does, in it or, for that matter, in Elena Knows. Of the three novels I read recently, this is the one I’m most likely to recommend to others, and I’m definitely going to read more of Piñeiro’s fiction, probably starting with A Little Luck, when I can get my hands on it.

And then there’s Claudia Piñeiro’s Betty Boo, which I found a really satisfying combination of smart plotting, thoughtful storytelling, and ideas that matter. In some ways it is less ambitious than the other two novels: it is structured more or less conventionally as a crime novel, and there aren’t really any narrative tricks to it, unless you count the sections that are ostensibly written by the protagonist, Nurit Iscar, about its central murder case. Iscar is a crime novelist who has had a professional setback (a crushing review of her foray into romantic fiction) and is currently getting by as a ghost writer. A contact at a major newspaper asks her to write some articles about a murder from a less journalistic and more contemplative perspective; in aid of this mission, she moves into the gated community where the victim lived and died. She ends up collaborating with the reporters on the crime beat as they investigate the death and discover that it is a part of a larger and more sinister operation—about which, of course, I will not give you any details here! Betty Boo is an unusual book: it doesn’t read quite like a “genre” mystery, as it is at least as interested in Nurit’s life and especially her relationships, with her close women friends and her lovers, as it is in its crime story. Also, Betty Boo is about crime, reporting, and fiction as themes, though its attention to these issues is integrated into the storytelling so that it never really feels metafictional—unlike Trust, which is all gimmick and so no substance, Betty Boo seems committed to the value and possibility of substance, even as Piñeiro provokes us to think about the obstacles we face in achieving it, in writing or in life, especially now that the news as a vehicle for both information and storytelling has become so degraded. I appreciated how original Betty Boo felt, and how genuinely interesting it was: I haven’t read another writer who does quite what Piñeiro does, in it or, for that matter, in Elena Knows. Of the three novels I read recently, this is the one I’m most likely to recommend to others, and I’m definitely going to read more of Piñeiro’s fiction, probably starting with A Little Luck, when I can get my hands on it. I’m running a bit behind on writing I need to get done sooner rather than later, but I don’t want to let Elizabeth Lowry’s The Chosen go unmentioned, so I thought I’d say at least little bit about it while it’s still fresh in my mind.

I’m running a bit behind on writing I need to get done sooner rather than later, but I don’t want to let Elizabeth Lowry’s The Chosen go unmentioned, so I thought I’d say at least little bit about it while it’s still fresh in my mind. And all of a sudden with the last mug in her hand, a message comes through loud and clear from her psyche: this is an accident. There is no need for her life to have worked out like this at all. So many other possibilities . . . How can this be her life, how can that be her love, if it rests on such accidents? Surely her real life is still waiting to happen . . . Surely the real thing has yet to come along.

And all of a sudden with the last mug in her hand, a message comes through loud and clear from her psyche: this is an accident. There is no need for her life to have worked out like this at all. So many other possibilities . . . How can this be her life, how can that be her love, if it rests on such accidents? Surely her real life is still waiting to happen . . . Surely the real thing has yet to come along.

Is it just me, or is there something there reminiscent of the third-person narrator in Bleak House, who also likes to rise above the landscape, giving an almost cinematic effect, and whose voice also rises in such moments into a visionary or prophetic tone? “Come, other future,” exclaims Spufford’s narrator; “Come, other chances. Come, unsounded deep. Come, undivided light”; “Come night, come darkness, for you cannot come too soon or stay too long by such a place as this!” exclaims Dickens’s. (I also heard a strong echo of Middlemarch in a passage about everyone finding themselves “the protagonist of the story. Every single one the centre of the world, around whom others revolve and events assemble.”)

Is it just me, or is there something there reminiscent of the third-person narrator in Bleak House, who also likes to rise above the landscape, giving an almost cinematic effect, and whose voice also rises in such moments into a visionary or prophetic tone? “Come, other future,” exclaims Spufford’s narrator; “Come, other chances. Come, unsounded deep. Come, undivided light”; “Come night, come darkness, for you cannot come too soon or stay too long by such a place as this!” exclaims Dickens’s. (I also heard a strong echo of Middlemarch in a passage about everyone finding themselves “the protagonist of the story. Every single one the centre of the world, around whom others revolve and events assemble.”)

Help me say what can’t be said, you ask me.

Help me say what can’t be said, you ask me. “It must be said,” Irina says to Concita, “that losing a child is the touchstone of grief, the gold standard of pain. The benchmark.” This is uncomfortable territory: it doesn’t seem right to weigh one grief against another. “Never would I compare my state with that of, say, a widow’s,” Denise Riley says in Time Lived, Without Its Flow”; “never would I lay claim to ‘the worst grief of all.'” Yet Riley, whose adult son died suddenly of a previously undetected heart defect, goes on to make other comparisons:

“It must be said,” Irina says to Concita, “that losing a child is the touchstone of grief, the gold standard of pain. The benchmark.” This is uncomfortable territory: it doesn’t seem right to weigh one grief against another. “Never would I compare my state with that of, say, a widow’s,” Denise Riley says in Time Lived, Without Its Flow”; “never would I lay claim to ‘the worst grief of all.'” Yet Riley, whose adult son died suddenly of a previously undetected heart defect, goes on to make other comparisons: