Already we are boldly launched upon the deep; but soon we shall be lost in its unshored, harborless immensities.

When I wrote about Madame Bovary here a couple of years ago, I commented that reading a very famous novel for the first time is

like meeting a celebrity in person (or so I imagine). It is intensely familiar and yet strange at the same time: it is exactly what it always appeared to be, and yet it is no longer an idea of something but the thing itself.

That certainly applies in this case too — more so, perhaps, because I think Moby-Dick has a larger presence in the popular imagination than Madame Bovary. And not just the things everyone “knows” about it (the white whale! Captain Ahab! “Call me Ishmael”!) but the book itself, which is a kind of legendary object, so deep and vast that reading it (or so you’d think) is itself a kind of fantastical quest.

So, once again, I find myself reading something that I already knew a lot about, and in the process discovering how little I really knew about it. So far, anyway, the surprise factor is much greater with Moby-Dick than it was with Madame Bovary (which really was the perfection of the sort of thing I expected it to be). I didn’t really know what Moby-Dick would actually sound like, and I especially had no idea (I don’t know why, but I really didn’t) that Moby-Dick would be so much fun. I also thought it would be much longer! I ended up getting the Penguin Classics edition — a choice I’m very happy with, as the font is very readable and the notes are helpful but not overwhelming — and it’s under 700 pages, which for someone who reads Vanity Fair, Middlemarch, and Bleak House regularly is not scary at all.

I decided against the highly- recommended Norton Critical edition because I wanted to approach this first reading not as a chore to be done diligently but as a reading experience to be, well, experienced! No doubt I will finish the novel without having plumbed its depths, and if I weren’t enjoying Melville’s prose so much first-hand, I might have changed my mind (and in fact I do have a copy of the Norton out from the library, ready to turn to if the need arises). I feel like Herman and I are doing pretty well so far, however.

I decided against the highly- recommended Norton Critical edition because I wanted to approach this first reading not as a chore to be done diligently but as a reading experience to be, well, experienced! No doubt I will finish the novel without having plumbed its depths, and if I weren’t enjoying Melville’s prose so much first-hand, I might have changed my mind (and in fact I do have a copy of the Norton out from the library, ready to turn to if the need arises). I feel like Herman and I are doing pretty well so far, however.

One reason for that, I’m quite sure, is that I’ve read Carlyle, which makes a lot of the wackier features of Moby-Dick (its rapid changes of register, from the prophetic to the bathetic; its elliptical allusions; its delight in the grotesque and the absurd; its insistence that everything — everything — is not just literal but symbolic) seem, if not necessarily reasonable and explicable, at least familiar. Here’s one of many examples of a moment that wouldn’t be out of place in Sartor Resartus:

Men may seem detestable as joint-stock companies and nations; knaves, fools, and murderers there may be; men may have mean and meagre faces; but man, in the ideal, is so noble and so sparkling, such a grand and glowing creature, that over any ignominious blemish in him all his fellows should run to throw their costliest robes. That immaculate manliness we feel within ourselves, so far within us, that it remains intact though all the outer character seem gone; bleeds with keenest anguish at the undraped spectacle of a valor-ruined man. Nor can piety itself, at such a shameful sight, completely stifle her upbraidings against the permitting stars. But this august dignity I treat of, is not the dignity of kings and robes, but that abounding dignity which has no robed investiture. Thou shalt see it shining in the arm that wields a pick or drives a spike; that democratic dignity which, on all hands, radiates without end from God; Himself! the great God absolute! The centre and circumstance of all democracy! His omnipresence, our divine equality!

All it needs is some more capital letters and it could be part of the unfolding of the Clothes Philosophy — or at any rate some kind of appendix to it.

I know from experience that not every reader finds Carlylean prose exhilarating, but I do: I have ever since I read The French Revolution as an unsuspecting undergraduate. What I loved about The French Revolution then (before I knew anything at all about Carlyle) was that it exuded the conviction that its writing absolutely mattered — that it was about something hugely important and written in a style meant to convey and to reproduce that significance. It was daring and unconventional because it had to be. I get the same feeling from Moby-Dick. Even when it’s going along a bit more quietly than in the passage I quoted, it has the humming energy of a book with something (many things!) it really, really wants to say, and to say in a memorable way. It doesn’t feel artful, if that means constructed to create an aesthetic effect: it feels spiritual — meaning not religious in any doctrinal way but about the spirit, about what matters, what drives us, what scares us, what means something to us. It’s exciting! I’d really rather quote from it (or read it aloud) than write about it!

I know from experience that not every reader finds Carlylean prose exhilarating, but I do: I have ever since I read The French Revolution as an unsuspecting undergraduate. What I loved about The French Revolution then (before I knew anything at all about Carlyle) was that it exuded the conviction that its writing absolutely mattered — that it was about something hugely important and written in a style meant to convey and to reproduce that significance. It was daring and unconventional because it had to be. I get the same feeling from Moby-Dick. Even when it’s going along a bit more quietly than in the passage I quoted, it has the humming energy of a book with something (many things!) it really, really wants to say, and to say in a memorable way. It doesn’t feel artful, if that means constructed to create an aesthetic effect: it feels spiritual — meaning not religious in any doctrinal way but about the spirit, about what matters, what drives us, what scares us, what means something to us. It’s exciting! I’d really rather quote from it (or read it aloud) than write about it!

That said, so far I can’t disagree with the contemporary opinion I’ve read that the book is an “intellectual chowder.” Up to the half-way point I’ve reached (Chapter 60) there has certainly been (off and on) a forward-moving narrative — I hesitate to call it a “plot” when really all that’s happened, in terms of events, is that Ishmael and Queequeg have met, signed on to the Pequod and been at sea for a while, including one “lowering” of the boats. That through-line is enough, but barely enough, to give some coherence to what is otherwise rather a jumble of anecdote, sea lore, nautical trivia, character sketches, and poetic outbursts. I like the divisions into short chapters, though: that helps each of those ingredients have a certain distinctness, and also mostly prevents them from feeling like digressions, because they are so clearly puzzle pieces. In fact, a metaphor that might work as well as the chowder one is patchwork: I wonder if anyone has worked up a theory of Moby-Dick as literary quilting.

I doubt it, because something else that’s hard to miss even on a first reading is just how very masculine the book is. I don’t recall that any women have even had any speaking parts at all in the novel so far — though I may be forgetting something, perhaps from back at the Spouter Inn. Certainly at sea it’s a man’s world. What does that mean for the oft-invoked universality of the novel’s mythos? Coincidentally, we’re watching Season 2 of The Affair, and last night’s episode featured a long scene between Noah and his therapist (played by Cynthia Nixon, which kept confusing me — why is Noah talking to Miranda?) in which Noah expounds a theory of greatness founded on abandoning ties — isn’t it more important to do (write) something great than to respect constraints like family and fidelity? What does it matter if other people suffer through your pursuit of greatness, especially if you achieve it? Obviously, in his case there’s a lot of wishful self-justification at work there, but what struck me was how much power that myth of greatness at any cost still has … when it’s a man talking, anyway. Not that Ahab (who is the most single-minded one in Moby-Dick) comes across as great; if he’s heroic, he is dangerously so, and presumably one thing the rest of the novel does is explore what is noble and what is disastrous about his quest for the white whale. (“And of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol. Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?”)

I doubt it, because something else that’s hard to miss even on a first reading is just how very masculine the book is. I don’t recall that any women have even had any speaking parts at all in the novel so far — though I may be forgetting something, perhaps from back at the Spouter Inn. Certainly at sea it’s a man’s world. What does that mean for the oft-invoked universality of the novel’s mythos? Coincidentally, we’re watching Season 2 of The Affair, and last night’s episode featured a long scene between Noah and his therapist (played by Cynthia Nixon, which kept confusing me — why is Noah talking to Miranda?) in which Noah expounds a theory of greatness founded on abandoning ties — isn’t it more important to do (write) something great than to respect constraints like family and fidelity? What does it matter if other people suffer through your pursuit of greatness, especially if you achieve it? Obviously, in his case there’s a lot of wishful self-justification at work there, but what struck me was how much power that myth of greatness at any cost still has … when it’s a man talking, anyway. Not that Ahab (who is the most single-minded one in Moby-Dick) comes across as great; if he’s heroic, he is dangerously so, and presumably one thing the rest of the novel does is explore what is noble and what is disastrous about his quest for the white whale. (“And of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol. Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?”)

I’m reading Moby-Dick because my book club chose it; we’re meeting next week to discuss the first 60 chapters, so I’m going to set it aside for other reading in the meantime so as not to muddle the conversation. I’ve already discovered that the fragmented structure makes putting it down and picking it up again easier than with books whose plots are more intricately woven (which is not to say that there aren’t continuities and patterns unifying Moby-Dick, particularly metaphorical ones). I’m really glad we did choose it: the suggestion was quite unexpected, and I was kind of skeptical about it when it was made, but now I’m grateful to have been giving that extra push. One more thing I’ll be able to cross off my ‘Humiliation’ list! (Maybe next I can suggest we read Ulysses … )

Technically, this post should really be called “This Week For My Classes,” since of course I’m not actually teaching any right now. In between other projects, though (mostly finishing a small essayish review of Mary Balogh’s Only Beloved for the next issue of Open Letters — yes, that’s right, I am trying my hand at writing a little bit about romance, thoughtfully, I hope, yet while avoiding the pitfalls of the dreaded “romance think piece”) I am chipping away at preparations for next year’s offerings, particularly the one completely new class, which is

Technically, this post should really be called “This Week For My Classes,” since of course I’m not actually teaching any right now. In between other projects, though (mostly finishing a small essayish review of Mary Balogh’s Only Beloved for the next issue of Open Letters — yes, that’s right, I am trying my hand at writing a little bit about romance, thoughtfully, I hope, yet while avoiding the pitfalls of the dreaded “romance think piece”) I am chipping away at preparations for next year’s offerings, particularly the one completely new class, which is  Following on that simple (if somewhat shoulder-shrugging) conclusion, I have decided not to spend a lot more time shopping for possible main texts to assign but just to call it for the ones that are my top candidates at this point, so that I can think about how to frame and teach them in particular (and what shorter texts to use to supplement them). So that means (I think – I haven’t actually placed the order with the bookstore yet)

Following on that simple (if somewhat shoulder-shrugging) conclusion, I have decided not to spend a lot more time shopping for possible main texts to assign but just to call it for the ones that are my top candidates at this point, so that I can think about how to frame and teach them in particular (and what shorter texts to use to supplement them). So that means (I think – I haven’t actually placed the order with the bookstore yet)  I’ve been looking at the syllabi for two of my colleagues who’ve taught this class recently and one thing that struck me is how many more readings they included. My big three won’t be my entire reading list, of course, but apparently I just take things more slowly than they do — they both typically take one week per novel, for instance (not super-long novels, but including, for example, King Solomon’s Mines, which is 300+ pages in the Penguin edition, or Frankenstein, which is around 200 pages). Looking at their schedules, I wondered if I should try to fit more in, so I did up a version of the timetable with Lady Audley’s Secret added — but unless I sped everything up more than I’m comfortable with, that meant leaving out most of the short fiction I’d included. In the end I think I’d rather allow lots of time to talk about particulars (and also take up class time with writing instruction, editing workshops, and that kind of thing — which I’m sure my colleagues do too, but I’m not sure how they manage to get it all done and still have robust discussions of so many complex readings). Pacing is one of the many mysteries of pedagogy, of course: there is no right rhythm, and what works depends on your own style as well as the purposes of the class. I usually spend three weeks on Middlemarch when I teach it in the 19th-century fiction class, but we take five weeks on it in Close Reading — and it would certainly be possible to take an entire semester for it, if only there were such a course (or, if only I dared to offer such a course and anyone actually took it!). Anyway, I reverted to a schedule with just three full-length novels, with short stories interspersed, and for now I like the looks of it. I can always order a fourth book later on if I change my mind. In the meantime, with the main titles chosen, I can set some parameters for my preparatory research.

I’ve been looking at the syllabi for two of my colleagues who’ve taught this class recently and one thing that struck me is how many more readings they included. My big three won’t be my entire reading list, of course, but apparently I just take things more slowly than they do — they both typically take one week per novel, for instance (not super-long novels, but including, for example, King Solomon’s Mines, which is 300+ pages in the Penguin edition, or Frankenstein, which is around 200 pages). Looking at their schedules, I wondered if I should try to fit more in, so I did up a version of the timetable with Lady Audley’s Secret added — but unless I sped everything up more than I’m comfortable with, that meant leaving out most of the short fiction I’d included. In the end I think I’d rather allow lots of time to talk about particulars (and also take up class time with writing instruction, editing workshops, and that kind of thing — which I’m sure my colleagues do too, but I’m not sure how they manage to get it all done and still have robust discussions of so many complex readings). Pacing is one of the many mysteries of pedagogy, of course: there is no right rhythm, and what works depends on your own style as well as the purposes of the class. I usually spend three weeks on Middlemarch when I teach it in the 19th-century fiction class, but we take five weeks on it in Close Reading — and it would certainly be possible to take an entire semester for it, if only there were such a course (or, if only I dared to offer such a course and anyone actually took it!). Anyway, I reverted to a schedule with just three full-length novels, with short stories interspersed, and for now I like the looks of it. I can always order a fourth book later on if I change my mind. In the meantime, with the main titles chosen, I can set some parameters for my preparatory research. I have done a few more small things for teaching prep too: I began adjusting the plans for my two fall courses — both of which I’ve taught a few times before — to fit the university’s revised fall schedule (which includes a week-long fall reading break for the first time), and I’ve started poking around on our new Learning Management System, Brightspace. So far I don’t like Brightspace at all, mostly because we seem to have chosen the version that doesn’t let us customize any of it, even the colours. That takes a lot of the fun out of it! Obviously the real purpose of these things is utilitarian, but the more you restrict what I can do with it, the more inclined I am to use it as a document dump and nothing else. People who’ve been using Brightspace for a while tell me they like it better than Blackboard, though, so I’m trying to stay optimistic that in ways I haven’t yet discovered, it’s actually an improvement and not just a change.

I have done a few more small things for teaching prep too: I began adjusting the plans for my two fall courses — both of which I’ve taught a few times before — to fit the university’s revised fall schedule (which includes a week-long fall reading break for the first time), and I’ve started poking around on our new Learning Management System, Brightspace. So far I don’t like Brightspace at all, mostly because we seem to have chosen the version that doesn’t let us customize any of it, even the colours. That takes a lot of the fun out of it! Obviously the real purpose of these things is utilitarian, but the more you restrict what I can do with it, the more inclined I am to use it as a document dump and nothing else. People who’ve been using Brightspace for a while tell me they like it better than Blackboard, though, so I’m trying to stay optimistic that in ways I haven’t yet discovered, it’s actually an improvement and not just a change. “In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.” – Fitzwilliam Darcy, in Pride and Prejudice

“In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.” – Fitzwilliam Darcy, in Pride and Prejudice Over the weekend I finally wrapped up my first ever run-through of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. When I started watching the series last summer, I actually came to it with remarkably little information and no preconceptions except that (and obviously I got over this one) it probably wasn’t going to be a hit with me, since vampires — and supernatural / fantasy stories generally — are just not something I gravitate towards. So why did I even bother giving it a try? Well, if enough people whose insights I have learned to trust and respect in other contexts find value in something, I’m usually willing to give it the benefit of the doubt, and often I’m won over. (

Over the weekend I finally wrapped up my first ever run-through of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. When I started watching the series last summer, I actually came to it with remarkably little information and no preconceptions except that (and obviously I got over this one) it probably wasn’t going to be a hit with me, since vampires — and supernatural / fantasy stories generally — are just not something I gravitate towards. So why did I even bother giving it a try? Well, if enough people whose insights I have learned to trust and respect in other contexts find value in something, I’m usually willing to give it the benefit of the doubt, and often I’m won over. ( The full series is a lot of episodes and I watched them over a period many months. I couldn’t begin, then, to write up any kind of comprehensive response. So far I’ve avoided what I know is an extensive body of commentary on it online and in print: I didn’t want my own impressions to get drowned out too fast! But if those of you who are longtime fans have any favorite essays, articles, or interviews, I’d be happy to be pointed in the right direction. (I know

The full series is a lot of episodes and I watched them over a period many months. I couldn’t begin, then, to write up any kind of comprehensive response. So far I’ve avoided what I know is an extensive body of commentary on it online and in print: I didn’t want my own impressions to get drowned out too fast! But if those of you who are longtime fans have any favorite essays, articles, or interviews, I’d be happy to be pointed in the right direction. (I know  2. Next, and probably most important, there’s Buffy herself. I was initially annoyed with how insubstantial she seemed. I got that her total ordinariness (besides the whole Slayer thing, of course) was part of the point, and the conflict between her calling and her longing to live a normal life is still potent in S7 (though by then it’s more complex and interesting). Still, for quite a long time I found her anti-intellectualism and general vapidity tedious. Qua high school (and then college) student, she seemed too much the antithesis of my own values. Everyone who told me she grows up a lot over the series was right, though, and her development seemed very believable, because she doesn’t transform so much as fill in the outline we get in the early seasons. Mature Buffy is still more instinctive than reflective, but those instincts get deeper. Also, as her petulance fades, her courage, moral integrity, and resolution make her increasingly admirable, and the increasing complexity of the situations she confronts makes her decisions correspondingly more interesting as well. A game-changing moment for me was her decision to kill Angel at the end of S2. I fully expected the just-in-time return of his soul to give us a pat happy ending, but that choice was much more dramatically interesting, for the plot and also for the development of Buffy’s character. (It was also the first time the show made me cry!) That she has to put her mission first always sets her apart, and it guarantees the fundamental loneliness that gives her both pathos and dignity in the later seasons.

2. Next, and probably most important, there’s Buffy herself. I was initially annoyed with how insubstantial she seemed. I got that her total ordinariness (besides the whole Slayer thing, of course) was part of the point, and the conflict between her calling and her longing to live a normal life is still potent in S7 (though by then it’s more complex and interesting). Still, for quite a long time I found her anti-intellectualism and general vapidity tedious. Qua high school (and then college) student, she seemed too much the antithesis of my own values. Everyone who told me she grows up a lot over the series was right, though, and her development seemed very believable, because she doesn’t transform so much as fill in the outline we get in the early seasons. Mature Buffy is still more instinctive than reflective, but those instincts get deeper. Also, as her petulance fades, her courage, moral integrity, and resolution make her increasingly admirable, and the increasing complexity of the situations she confronts makes her decisions correspondingly more interesting as well. A game-changing moment for me was her decision to kill Angel at the end of S2. I fully expected the just-in-time return of his soul to give us a pat happy ending, but that choice was much more dramatically interesting, for the plot and also for the development of Buffy’s character. (It was also the first time the show made me cry!) That she has to put her mission first always sets her apart, and it guarantees the fundamental loneliness that gives her both pathos and dignity in the later seasons. 4. …which brings me to the Scoobies. Sure, Buffy is the leader, and I warmed to her, but it’s the ensemble makes the show magic. I didn’t love every member of it equally (I didn’t miss Oz when he drove away, for instance, and I thought Tara was always a weak link — but Anya became a favorite, and I even got pretty fond of Andrew by the end) but the core friendships really mattered to me after a while: there’s something so absolute about their love and trust for each other, and so touching about the way they all, given the chance, can rescue each other. It isn’t always Buffy who saves the day, and it’s not Buffy alone who (over and over!) saves the world.

4. …which brings me to the Scoobies. Sure, Buffy is the leader, and I warmed to her, but it’s the ensemble makes the show magic. I didn’t love every member of it equally (I didn’t miss Oz when he drove away, for instance, and I thought Tara was always a weak link — but Anya became a favorite, and I even got pretty fond of Andrew by the end) but the core friendships really mattered to me after a while: there’s something so absolute about their love and trust for each other, and so touching about the way they all, given the chance, can rescue each other. It isn’t always Buffy who saves the day, and it’s not Buffy alone who (over and over!) saves the world.

6. … the Big Bad! For me, this aspect of the show was always its biggest weakness. I appreciate the value of a larger plot arc to give each season continuity, but the super-villains always just got so irritating by the end! Worst, I think, was Adam from S4, but S5’s Glory is a close second for sheer flamboyant tedium. I enjoyed the evil Mayor in S3, and I found the Trio pretty funny in S6, though I guess they did kind of trivialize the process. (There wasn’t anything trivial about Willow flaying Warren alive, though!) Bad Angel was really interesting, and Spike was a delightfully gleeful villain in the early years. In S7, I thought some interesting things went on with The First, especially the coming and going as different characters from the past. I was very annoyed, though, by the pendant-ex-machina that brought about The First’s climactic defeat. (And why is it Spike who becomes both hero and martyr — shouldn’t that final victory have belonged to Buffy, or to the newly-minted Slayers collectively? And why didn’t Spike — or Anya! — survive the final battle?!)

6. … the Big Bad! For me, this aspect of the show was always its biggest weakness. I appreciate the value of a larger plot arc to give each season continuity, but the super-villains always just got so irritating by the end! Worst, I think, was Adam from S4, but S5’s Glory is a close second for sheer flamboyant tedium. I enjoyed the evil Mayor in S3, and I found the Trio pretty funny in S6, though I guess they did kind of trivialize the process. (There wasn’t anything trivial about Willow flaying Warren alive, though!) Bad Angel was really interesting, and Spike was a delightfully gleeful villain in the early years. In S7, I thought some interesting things went on with The First, especially the coming and going as different characters from the past. I was very annoyed, though, by the pendant-ex-machina that brought about The First’s climactic defeat. (And why is it Spike who becomes both hero and martyr — shouldn’t that final victory have belonged to Buffy, or to the newly-minted Slayers collectively? And why didn’t Spike — or Anya! — survive the final battle?!)

Where does the time go? It seems like I only just finished reading

Where does the time go? It seems like I only just finished reading  I have also been reading, in dribs and drabs, the critical books I’ve collected about romance fiction and Westerns, taking some first steps towards prepping for next winter’s ‘Pulp Fiction’ class. I have been enjoying the new ideas and frameworks raised by these materials, and they have started a lot of things turning around in my head. But since I haven’t been working on them in a very concentrated way this week I haven’t felt I had anything in particular to say. I’m sure I will! And I have also been kicking around, in a very preliminary way, how I might organize the course, and especially the readings. I am puzzling, for instance, about whether it would work to assign only full-length novels in a first-year course. I have taught many different incarnations of our introductory classes, but every one has included some blend of short and long readings. Short ones, of course, have many advantages when you’re working with beginning students: they can get the whole thing read reasonably quickly and you can begin to practice the analytical skills you want them to learn with material they can easily manage. Then you can build up to longer texts. In some of the genres we’ll cover (detective fiction, for instance) it is easy enough to find good short options, but this seems harder to do with romance. (I found one that I think might work quite well — Liz Fielding’s “Secret Wedding,” which is cleverly metafictional about romance conventions — but it seems to be available only in a Kindle edition, and I’m currently stumped about whether that rules it out as a required reading.) I’ve also been thinking about starting with some Victorian ‘pulp,’ specifically Lady Audley’s Secret — but I’m worried that they might bog down in it, especially if it’s the first thing we read. You can look forward to (or dread, I guess) many more updates as my thinking about this course develops. And, as always, I will welcome input!

I have also been reading, in dribs and drabs, the critical books I’ve collected about romance fiction and Westerns, taking some first steps towards prepping for next winter’s ‘Pulp Fiction’ class. I have been enjoying the new ideas and frameworks raised by these materials, and they have started a lot of things turning around in my head. But since I haven’t been working on them in a very concentrated way this week I haven’t felt I had anything in particular to say. I’m sure I will! And I have also been kicking around, in a very preliminary way, how I might organize the course, and especially the readings. I am puzzling, for instance, about whether it would work to assign only full-length novels in a first-year course. I have taught many different incarnations of our introductory classes, but every one has included some blend of short and long readings. Short ones, of course, have many advantages when you’re working with beginning students: they can get the whole thing read reasonably quickly and you can begin to practice the analytical skills you want them to learn with material they can easily manage. Then you can build up to longer texts. In some of the genres we’ll cover (detective fiction, for instance) it is easy enough to find good short options, but this seems harder to do with romance. (I found one that I think might work quite well — Liz Fielding’s “Secret Wedding,” which is cleverly metafictional about romance conventions — but it seems to be available only in a Kindle edition, and I’m currently stumped about whether that rules it out as a required reading.) I’ve also been thinking about starting with some Victorian ‘pulp,’ specifically Lady Audley’s Secret — but I’m worried that they might bog down in it, especially if it’s the first thing we read. You can look forward to (or dread, I guess) many more updates as my thinking about this course develops. And, as always, I will welcome input!

Ebershoff ties Greta’s journey as a painter to Lili’s emergence: it’s Greta’s invitation to Einar to model for her in women’s stockings that precipitates Lili’s emergence, and it’s her paintings of Lili that propel Greta into prominence as an artist even as Einar, initially the more successful of the two, fades into artistic insigificance. Ebershoff’s prose is beautiful throughout — lyrical but precise, poignant but restrained — but it rises to something like exuberance when he writes about her painting:

Ebershoff ties Greta’s journey as a painter to Lili’s emergence: it’s Greta’s invitation to Einar to model for her in women’s stockings that precipitates Lili’s emergence, and it’s her paintings of Lili that propel Greta into prominence as an artist even as Einar, initially the more successful of the two, fades into artistic insigificance. Ebershoff’s prose is beautiful throughout — lyrical but precise, poignant but restrained — but it rises to something like exuberance when he writes about her painting: A friend of mine highly recommended Kent Haruf’s Plainsong, but when I looked for it at the bookstore they didn’t have it, so instead I brought home his more recent novel Benediction. It seems to me to have been a happy enough substitution: Plainsong may yet turn out to be better, but I thought Benediction was very good.

A friend of mine highly recommended Kent Haruf’s Plainsong, but when I looked for it at the bookstore they didn’t have it, so instead I brought home his more recent novel Benediction. It seems to me to have been a happy enough substitution: Plainsong may yet turn out to be better, but I thought Benediction was very good. Dad is at the center of Benediction, but the novel’s attention radiates out from him to the small struggles and successes of those around him. Notable among these is the town minister, Rob Lyle, who has been sent to the town of Holt after causing trouble in Denver — trouble he ends up reiterating in Holt because (as he says in his own defense) “I had to say it . . . It’s the truth.” The truth he preaches is love, which sounds common enough except that he suggests people should really mean it, not just pay lip service to it:

Dad is at the center of Benediction, but the novel’s attention radiates out from him to the small struggles and successes of those around him. Notable among these is the town minister, Rob Lyle, who has been sent to the town of Holt after causing trouble in Denver — trouble he ends up reiterating in Holt because (as he says in his own defense) “I had to say it . . . It’s the truth.” The truth he preaches is love, which sounds common enough except that he suggests people should really mean it, not just pay lip service to it: I’m pleased to announce that I’ve completed one of my first summer projects: turning the materials for my

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve completed one of my first summer projects: turning the materials for my  When I posted about Brooklyn

When I posted about Brooklyn  I understand that this can be taken as symptomatic of Eilis’s character. Early in her first year in Brooklyn she recognizes that her survival there in fact depends on suppressing her feelings:

I understand that this can be taken as symptomatic of Eilis’s character. Early in her first year in Brooklyn she recognizes that her survival there in fact depends on suppressing her feelings: I feel as if I should begin with a disclaimer: this post is just a preliminary attempt to sort something out for myself that I am sure has been discussed a lot already! I know it’s not a new question, but it is a new one for me to be thinking carefully about — and that’s what my blog is for, not for presenting absolutely finished position papers but for exploration. So don’t jump on me if, for you, this is old news or already a settled question! Instead, tell me what you think, since one thing I’m hoping will come from writing a little about this question here is that I’ll get some leads and ideas for how to think about it better, or where to read more about it.

I feel as if I should begin with a disclaimer: this post is just a preliminary attempt to sort something out for myself that I am sure has been discussed a lot already! I know it’s not a new question, but it is a new one for me to be thinking carefully about — and that’s what my blog is for, not for presenting absolutely finished position papers but for exploration. So don’t jump on me if, for you, this is old news or already a settled question! Instead, tell me what you think, since one thing I’m hoping will come from writing a little about this question here is that I’ll get some leads and ideas for how to think about it better, or where to read more about it. Not that there’s anything wrong with that! Lots of (maybe even most) critical work is at least implicitly advocating on behalf of its specific topic — whether for its underestimated importance to literary history or for its political efficacy or for a right understanding of its aesthetic properties. Romance is a special case, too: as pretty much everyone I’ve read who writes about romance says at some point, it seems to call for overt special pleading simply because it is so routinely dismissed and its readers and writers so routinely shamed. If Regis seems at times to protest too much, it’s probably just that she knew her choice of subject would be met with skepticism, if not derision, and not just by her academic colleagues. (I expect that more recent scholarship is less defensive, as genre fiction and popular culture more generally have become increasingly familiar parts of the academic landscape. Eric Selinger and Sarah Frantz’s collection New Approaches to Popular Romance Fiction, which came out in 2012, is also on my reading list; I’ll be curious to see if I’m right that the tone has changed.)

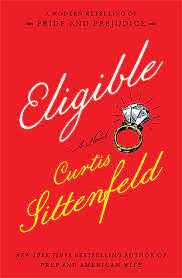

Not that there’s anything wrong with that! Lots of (maybe even most) critical work is at least implicitly advocating on behalf of its specific topic — whether for its underestimated importance to literary history or for its political efficacy or for a right understanding of its aesthetic properties. Romance is a special case, too: as pretty much everyone I’ve read who writes about romance says at some point, it seems to call for overt special pleading simply because it is so routinely dismissed and its readers and writers so routinely shamed. If Regis seems at times to protest too much, it’s probably just that she knew her choice of subject would be met with skepticism, if not derision, and not just by her academic colleagues. (I expect that more recent scholarship is less defensive, as genre fiction and popular culture more generally have become increasingly familiar parts of the academic landscape. Eric Selinger and Sarah Frantz’s collection New Approaches to Popular Romance Fiction, which came out in 2012, is also on my reading list; I’ll be curious to see if I’m right that the tone has changed.) Regis is completely right that by her definition, Pride and Prejudice is a romance novel. But here’s the thing: to me, that suggests she’s using the wrong definition. First of all, it’s too broad to be interesting (even her list of canonical “romances” hardly seems to hang together in a meaningful way, outside a very bare skeletal similarity). It also seems anachronistic, in the same way that calling The Moonstone a “mystery” does: there wasn’t really such a category at the time (that’s not really the kind of book Collins himself thought he was writing), and applying our current terms so absolutely means losing sight of the genealogy of our modern genres. Books can be closely related in kind (or, as Regis sets it up, in structure) with being the same kind exactly.

Regis is completely right that by her definition, Pride and Prejudice is a romance novel. But here’s the thing: to me, that suggests she’s using the wrong definition. First of all, it’s too broad to be interesting (even her list of canonical “romances” hardly seems to hang together in a meaningful way, outside a very bare skeletal similarity). It also seems anachronistic, in the same way that calling The Moonstone a “mystery” does: there wasn’t really such a category at the time (that’s not really the kind of book Collins himself thought he was writing), and applying our current terms so absolutely means losing sight of the genealogy of our modern genres. Books can be closely related in kind (or, as Regis sets it up, in structure) with being the same kind exactly. Alternatively, you could argue (as I have seen done) that romance, like all genres, comes in both “high” and “low” — or literary and popular — versions.** There’s still a kind of hierarchy, but now you’re separating out those who “transcend the genre” (to use the phrase Ian Rankin hates when applied to crime fiction) from those who happily take their place within it. No direct comparisons are called for, then, and Heyer or Chase (or choose your preferred exemplars) get considered more or less on their own terms. I still think the larger category (the one being subdivided into high and low forms) conflates too many different kinds of things, and the end result can be condescending — it implies, or could, that the serious stuff is going on in some sense over the heads of both readers and writers of the popular incarnations of the genre, or that those who really take themselves and their work seriously will aim at that transcendent kind. But at least this approach doesn’t pretend all novels organized around love and marriage are the same kind of books.

Alternatively, you could argue (as I have seen done) that romance, like all genres, comes in both “high” and “low” — or literary and popular — versions.** There’s still a kind of hierarchy, but now you’re separating out those who “transcend the genre” (to use the phrase Ian Rankin hates when applied to crime fiction) from those who happily take their place within it. No direct comparisons are called for, then, and Heyer or Chase (or choose your preferred exemplars) get considered more or less on their own terms. I still think the larger category (the one being subdivided into high and low forms) conflates too many different kinds of things, and the end result can be condescending — it implies, or could, that the serious stuff is going on in some sense over the heads of both readers and writers of the popular incarnations of the genre, or that those who really take themselves and their work seriously will aim at that transcendent kind. But at least this approach doesn’t pretend all novels organized around love and marriage are the same kind of books.