They are worth more to us than the empty human shells we have taken them for; they were children who cried for their mothers, they were young women who fell in love; they endured childbirth, the death of parents; they laughed, and they celebrated Christmas. They argued with their siblings, they wept, they dreamed, they hurt, they enjoyed small triumphs.

They are worth more to us than the empty human shells we have taken them for; they were children who cried for their mothers, they were young women who fell in love; they endured childbirth, the death of parents; they laughed, and they celebrated Christmas. They argued with their siblings, they wept, they dreamed, they hurt, they enjoyed small triumphs.

Hallie Rubenhold’s The Five admirably fulfill’s Rubenhold’s stated ambition for it: to restore “their dignity” to five women whose individual life stories have been subsumed by the horror of their deaths and the horrifyingly glamourous mythology of their murderer. These women, the “canonical five” victims of Jack the Ripper, have long been cast as bit players in his drama, in parts that, Rubenhold shows, reduce or misrepresent who they actually were.

I’m not going to reiterate the life stories Rubenhold has (somewhat astonishingly) managed to reconstruct in The Five, partly because it’s the sheer accumulation of detail that matters to the book’s effectiveness. At times I did wonder if we really need so much detail—Rubenhold risks bogging us down in minutiae, and I admit that sometimes I found myself starting to skim, looking to reconnect with a storyline, to regain some forward momentum. But even as I did that, I was aware that I was going against the grain of the book, which is by design anti-narrative.

What I mean by that (and of course this is just my theory about Rubenhold’s approach) is that we already know something crucial about each woman: we already know how their stories end. For too long that one thing has been considered enough to know about them, or at least the most important thing to know about them, and it has been used to make assumptions about what came before—and about who these women were. In order to undo that ending, to refuse it as the defining moment in their lives, Rubenhold has to repress it almost completely, even as each step of each of her five biographies takes its subject closer and closer to it. It’s a really interesting conceptual challenge.

She is also committed to undoing the sensationalism around her subjects’ lives and deaths: I think that’s another explanation for the way she writes the book. She avoids all the obvious kinds of narrative manipulation: she creates no suspense, she does not set a foreboding tone, use foreshadowing, or create melodramatic scenarios or dramatic climaxes. This is one way The Five differs from Dean Jobb’s The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: although I did not find his treatment of this murderer’s victims exploitive, Jobb does enjoy dramatic irony and foreshadowing, and overall he tells a more melodramatic and grisly tale. He also, obviously, focuses on the killer, whereas Rubenhold refuses to give Jack the Ripper any more attention than is absolutely necessary. (For instance, there is no speculation at all in The Five about who he was.)

She is also committed to undoing the sensationalism around her subjects’ lives and deaths: I think that’s another explanation for the way she writes the book. She avoids all the obvious kinds of narrative manipulation: she creates no suspense, she does not set a foreboding tone, use foreshadowing, or create melodramatic scenarios or dramatic climaxes. This is one way The Five differs from Dean Jobb’s The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: although I did not find his treatment of this murderer’s victims exploitive, Jobb does enjoy dramatic irony and foreshadowing, and overall he tells a more melodramatic and grisly tale. He also, obviously, focuses on the killer, whereas Rubenhold refuses to give Jack the Ripper any more attention than is absolutely necessary. (For instance, there is no speculation at all in The Five about who he was.)

This is not to say that The Five is a dull, plodding, or wearily studious book, though it is very much a work of social history. It gets its considerable energy from Rubenhold’s frankly feminist perspective on her subjects’ lives, deaths, and posthumous treatment. “The courses their lives took,” she says early on, “mirrored that of so many other women of the Victorian age.” The book is really one long quietly furious riposte to the still too-common victim-blaming question about women who are assaulted: “what was she doing there in the first place?” She answers that question five times, recounting how one by one these women were worn down by social constraints, by economic struggles, by lack of education, by lack of employment options, by their inability to control their fertility; she shows families broken by disease, by poverty, by alcoholism, and especially by the lack of support and resources to recover from any of these problems. The women she tells us about were not helpless victims of circumstance, but their world was hard, hostile, and often dangerous—and profoundly misogynistic. They ended up in vulnerable situations, not because they made uniquely bad decisions or were in any way “looking for it,” but because they had run out of other options.

And no matter how they came to be “sleeping rough,” they didn’t invite or deserve their horrendous deaths. The idea that any version of their life stories should mitigate our distress at the violence done to them—that in any way their murders open them up to that kind of judgment of their characters—is precisely what Rubenhold is crusading against. The epigraph for her conclusion comes from the judge at the trial of the so-called “Suffolk Strangler” in 2008: “You may view with some distaste the lifestyles of those involved,” he says, but “no-one is entitled to do these women any harm, let alone kill them.” Since the first inquests into their deaths, Rubenhold shows, her five have been dismissed as “only prostitutes,” perpetuating the familiar Madonna / whore dichotomy that “suggests there is an acceptable standard of female behavior, and those who deviate from it are fit to be punished.” She rightly points out how persistent this view is, to this day:

And no matter how they came to be “sleeping rough,” they didn’t invite or deserve their horrendous deaths. The idea that any version of their life stories should mitigate our distress at the violence done to them—that in any way their murders open them up to that kind of judgment of their characters—is precisely what Rubenhold is crusading against. The epigraph for her conclusion comes from the judge at the trial of the so-called “Suffolk Strangler” in 2008: “You may view with some distaste the lifestyles of those involved,” he says, but “no-one is entitled to do these women any harm, let alone kill them.” Since the first inquests into their deaths, Rubenhold shows, her five have been dismissed as “only prostitutes,” perpetuating the familiar Madonna / whore dichotomy that “suggests there is an acceptable standard of female behavior, and those who deviate from it are fit to be punished.” She rightly points out how persistent this view is, to this day:

When a woman steps out of line and contravenes accepted norms of feminine behavior, whether on social media or on the Victorian street, there is a tacit understanding that someone must put her back in her place.

Never having read any “Ripperology,” I was shocked at the examples she gives of writers (recent ones!) about Jack the Ripper who casually degrade his victims and “elevate the murderer to celebrity status.” “Our culture’s obsession with the mythology,” she convincingly argues, “serves only to normalize its particular brand of misogyny.” Women shouldn’t have to be nice, good, perfect to be safe; men shouldn’t be able to use anything about women’s lives as justifications for violence against them. It might seem like a stretch when Rubenhold declares that by accepting the “Ripper legend” we not only perpetuate the specific injustice done to her subjects but “condone the basest forms of violence”—but if we understand them, as she wants us to, as representative rather than unique, as important because they are ordinary, not because they are outliers, then she is exactly right, and in that respect The Five is very much a book about the present as well as the past, and it is not just sad but infuriating.

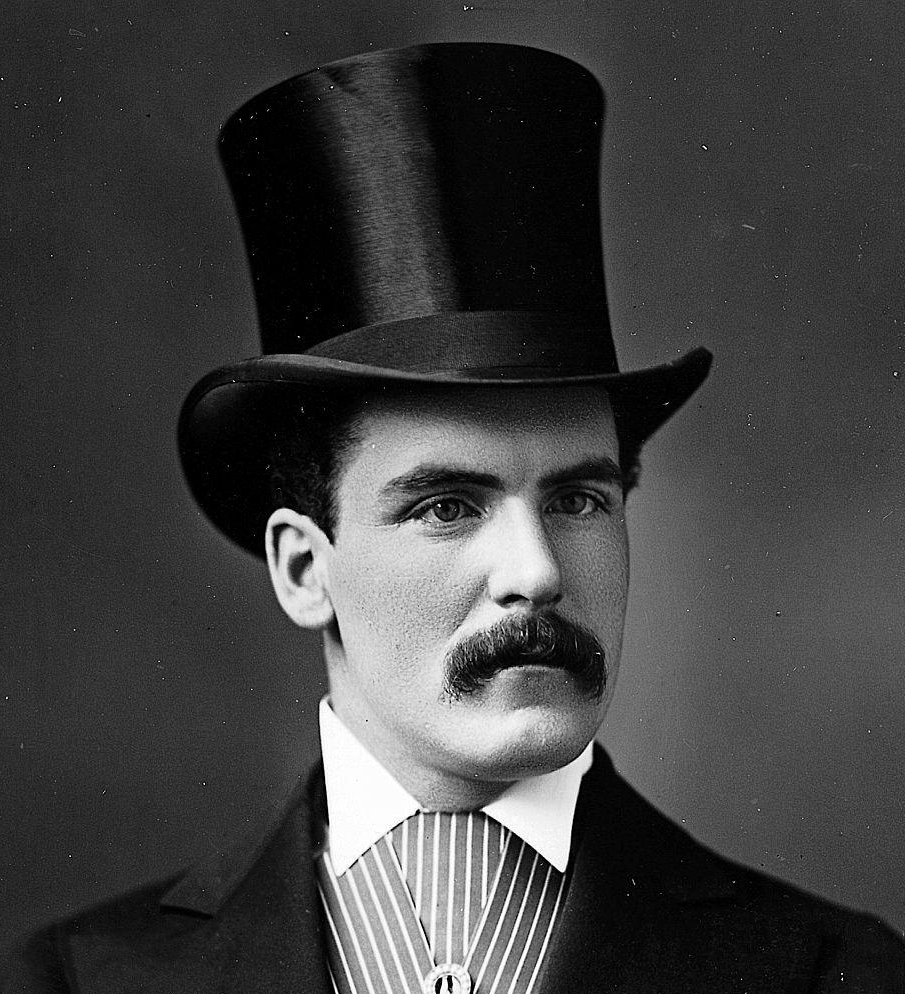

And Cream really was evil. For all Cream’s notoriety, both in the 1890s and among aficionados of serial killers in general and Jack the Ripper in particular, I knew nothing about him before reading this book. A lot of the fun (if that’s the right word!) of The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream is following the trail of his known and suspected killings, as well as the twists and turns of various efforts over decades to prove his guilt definitively—so I won’t go into detail about all that here. Jobb’s research is extensive and meticulous: he explains in a note on his sources that “every scene is based on a contemporary description of what occurred and where events unfolded; all quotations and dialogue are presented as they were recorded in newspaper reports, memoirs, police reports, and transcripts of court proceedings.” The result is a remarkably specific and vivid account that gives a really complete picture of everything except what is perhaps the most baffling and disturbing aspect of the case: why Cream did what he did. Jobb notes that the concept of “serial killer” was not around at the time of Cream’s murders, and neither was “psychopath.” An attempt was made after his (last) trial to argue that he was legally insane, but it did not prevail. All that could really be said about him was that he was a monster.

And Cream really was evil. For all Cream’s notoriety, both in the 1890s and among aficionados of serial killers in general and Jack the Ripper in particular, I knew nothing about him before reading this book. A lot of the fun (if that’s the right word!) of The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream is following the trail of his known and suspected killings, as well as the twists and turns of various efforts over decades to prove his guilt definitively—so I won’t go into detail about all that here. Jobb’s research is extensive and meticulous: he explains in a note on his sources that “every scene is based on a contemporary description of what occurred and where events unfolded; all quotations and dialogue are presented as they were recorded in newspaper reports, memoirs, police reports, and transcripts of court proceedings.” The result is a remarkably specific and vivid account that gives a really complete picture of everything except what is perhaps the most baffling and disturbing aspect of the case: why Cream did what he did. Jobb notes that the concept of “serial killer” was not around at the time of Cream’s murders, and neither was “psychopath.” An attempt was made after his (last) trial to argue that he was legally insane, but it did not prevail. All that could really be said about him was that he was a monster. As part of my current research on issues related to gender, genre, and the ‘novel of purpose’ (about which more eventually, when it takes on a clearer shape!) I asked our indefatigable Document Delivery staff to bring in a copy of Vera Brittain’s On Becoming a Writer (1947). It turns out to be in large part advice for aspiring authors, and I’ve been amused, reading it, by how familiar a lot of it sounds as well as how practical and discouraging Brittain is. I thought you might be amused as well, so here’s her list of “nine widely-held illusions regarding the literary life,” in her own words, along with some of her blunt recommendations for overcoming these “phantasies.”

As part of my current research on issues related to gender, genre, and the ‘novel of purpose’ (about which more eventually, when it takes on a clearer shape!) I asked our indefatigable Document Delivery staff to bring in a copy of Vera Brittain’s On Becoming a Writer (1947). It turns out to be in large part advice for aspiring authors, and I’ve been amused, reading it, by how familiar a lot of it sounds as well as how practical and discouraging Brittain is. I thought you might be amused as well, so here’s her list of “nine widely-held illusions regarding the literary life,” in her own words, along with some of her blunt recommendations for overcoming these “phantasies.” Having cleared away these sad illusions, Brittain moves on in the next chapter (“First Essentials”) to offer some positive suggestions, though not without one more chastening reminder that your “desire for fame, wealth, and distinguished acquaintances does not in itself constitute a claim to literary success.” There really is something bracing about her Eeyore-like insistence that, while writing may well be worth the effort, it almost certainly won’t be fun, that it’s more likely than not that you aren’t very special or talented, and that the way forward is mostly drudgery. Would a book, not of this type (there are many such) but with this tone get published today? So far—I haven’t read to the end yet—it is certainly the antithesis of Elizabeth Gilbert’s irritating paean to half-assed creativity

Having cleared away these sad illusions, Brittain moves on in the next chapter (“First Essentials”) to offer some positive suggestions, though not without one more chastening reminder that your “desire for fame, wealth, and distinguished acquaintances does not in itself constitute a claim to literary success.” There really is something bracing about her Eeyore-like insistence that, while writing may well be worth the effort, it almost certainly won’t be fun, that it’s more likely than not that you aren’t very special or talented, and that the way forward is mostly drudgery. Would a book, not of this type (there are many such) but with this tone get published today? So far—I haven’t read to the end yet—it is certainly the antithesis of Elizabeth Gilbert’s irritating paean to half-assed creativity

Solitude: it’s become my trade. As it requires a certain discipline, it’s a condition I try to perfect. And yet it plagues me, it weighs on me, in spite of my knowing it so well. It’s probably my mother’s influence. She’s always been afraid of being alone and now her life as an old woman torments her, so much that when I call to ask how she’s doing, she just says, I’m very alone.

Solitude: it’s become my trade. As it requires a certain discipline, it’s a condition I try to perfect. And yet it plagues me, it weighs on me, in spite of my knowing it so well. It’s probably my mother’s influence. She’s always been afraid of being alone and now her life as an old woman torments her, so much that when I call to ask how she’s doing, she just says, I’m very alone. I thought Whereabouts really beautifully captured the paradox that isolation is not, or at least not only, about being alone. “If I tell my mother that I’m grateful to be on my own,” says the narrator,

I thought Whereabouts really beautifully captured the paradox that isolation is not, or at least not only, about being alone. “If I tell my mother that I’m grateful to be on my own,” says the narrator, A lot of emotion is submerged in Whereabouts. I didn’t love

A lot of emotion is submerged in Whereabouts. I didn’t love  Like many Canadians, I decided that the best way to mark Canada Day this year was to reflect rather than celebrate. I have remarked here

Like many Canadians, I decided that the best way to mark Canada Day this year was to reflect rather than celebrate. I have remarked here  Wagamese writes vividly about the landscape and the Ojibway traditions that shape Saul’s identity and the pain of being forced away from them and from his family. He also writes really well about hockey: as someone who has never been at all interested in hockey (or any sport), I was surprised how beautiful and exciting some of these sequences were to read. Hockey’s centrality to (many people’s idea of) Canadian identity makes Saul’s story of finding freedom on the ice and then having that joy and his spirit broken by racism an effective way of saying something broader about Canada’s rifts and failures as a nation. The road Saul takes from that breaking point back to some kind of peace, with himself and with hockey, is a hopeful version of a story that both the novel and the news tell us doesn’t always end that way.

Wagamese writes vividly about the landscape and the Ojibway traditions that shape Saul’s identity and the pain of being forced away from them and from his family. He also writes really well about hockey: as someone who has never been at all interested in hockey (or any sport), I was surprised how beautiful and exciting some of these sequences were to read. Hockey’s centrality to (many people’s idea of) Canadian identity makes Saul’s story of finding freedom on the ice and then having that joy and his spirit broken by racism an effective way of saying something broader about Canada’s rifts and failures as a nation. The road Saul takes from that breaking point back to some kind of peace, with himself and with hockey, is a hopeful version of a story that both the novel and the news tell us doesn’t always end that way. Memorable, readable, topical – and yet I also found Indian Horse a bit dissatisfying, a reaction I might have avoided if I had approached it as a young adult novel, which it turns out to be … maybe? I didn’t think it was when I ordered it, but as I was reading it and thinking that, for all its difficult subject matter, it seemed stylistically unsophisticated and often quite heavy-handed, it occurred to me that it felt like YA fiction and I looked it up and found that it won an award for YA fiction. Aha! That explained it! Or does it? Because I looked around some more and could not confirm that Indian Horse was written or marketed as YA fiction. That left me wondering if or how that question should matter to my judgment of how good a novel Indian Horse is. I don’t look down on fiction written for young(er) readers. I cherish and

Memorable, readable, topical – and yet I also found Indian Horse a bit dissatisfying, a reaction I might have avoided if I had approached it as a young adult novel, which it turns out to be … maybe? I didn’t think it was when I ordered it, but as I was reading it and thinking that, for all its difficult subject matter, it seemed stylistically unsophisticated and often quite heavy-handed, it occurred to me that it felt like YA fiction and I looked it up and found that it won an award for YA fiction. Aha! That explained it! Or does it? Because I looked around some more and could not confirm that Indian Horse was written or marketed as YA fiction. That left me wondering if or how that question should matter to my judgment of how good a novel Indian Horse is. I don’t look down on fiction written for young(er) readers. I cherish and  What with servants, chasms, and signboards, Constance considered that her life as a married woman would not be deficient in excitement.

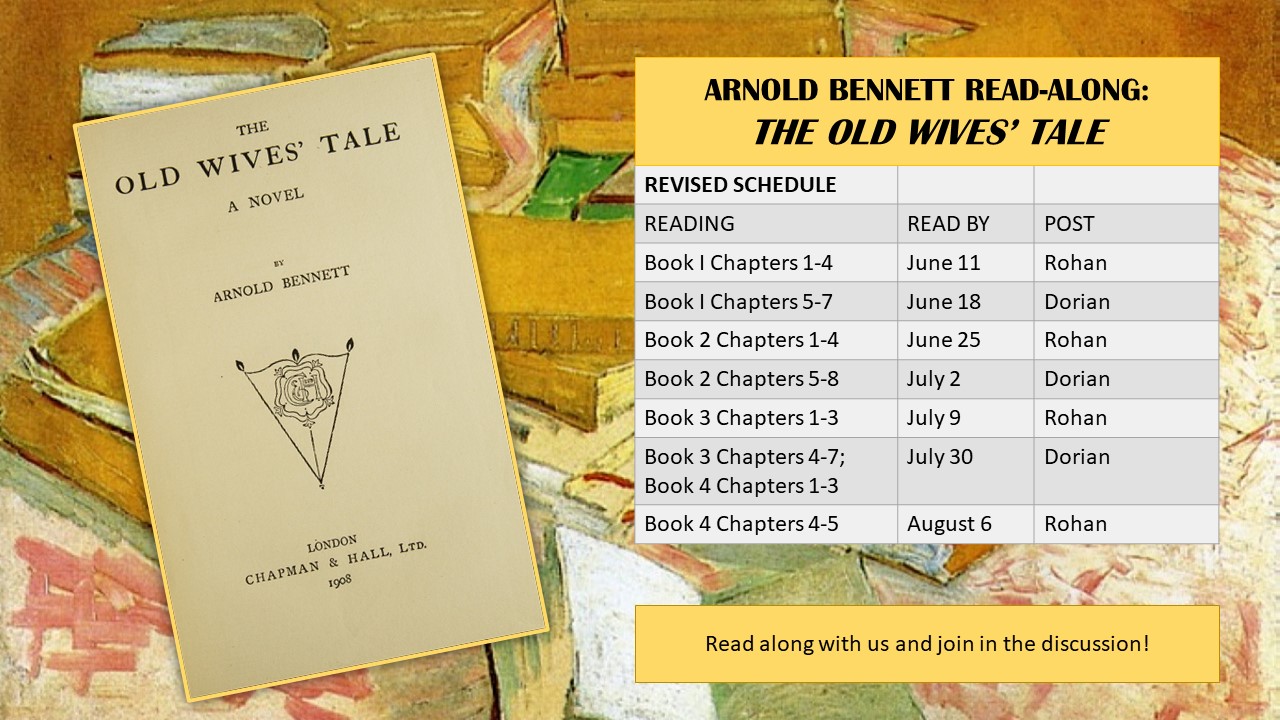

What with servants, chasms, and signboards, Constance considered that her life as a married woman would not be deficient in excitement. It is certainly striking already how much Constance’s life has changed since we first met her. In these four chapters she has: gotten married and moved into her parents’ bed; hired a new servant; acquired a dog; been astonished by her husband’s installation of a signboard for the shop; discovered that her husband is a smoker; hosted her first family Christmas; had a baby (and been through a number of parenting crises); and lost her mother. Bennett’s choice of things to highlight confuses me: too much attention goes to what seem like the wrong things, unimportant things (the bed, the dog, the smoking, the signboard). But maybe it only seems this way because I don’t quite get what Bennett is doing with them. There’s such a long section about the bed, for example. In a way, it is a nice set piece: it effectively conveys the disorientation and poignancy of growing up, of realizing that your place in the cycle of life has changed. The description of Constance lying in bed waiting for her husband is also quite sensual:

It is certainly striking already how much Constance’s life has changed since we first met her. In these four chapters she has: gotten married and moved into her parents’ bed; hired a new servant; acquired a dog; been astonished by her husband’s installation of a signboard for the shop; discovered that her husband is a smoker; hosted her first family Christmas; had a baby (and been through a number of parenting crises); and lost her mother. Bennett’s choice of things to highlight confuses me: too much attention goes to what seem like the wrong things, unimportant things (the bed, the dog, the smoking, the signboard). But maybe it only seems this way because I don’t quite get what Bennett is doing with them. There’s such a long section about the bed, for example. In a way, it is a nice set piece: it effectively conveys the disorientation and poignancy of growing up, of realizing that your place in the cycle of life has changed. The description of Constance lying in bed waiting for her husband is also quite sensual: Probably the part of this instalment that surprised me the most, in that respect, was the lengthy section from infant Cyril’s point of view.

Probably the part of this instalment that surprised me the most, in that respect, was the lengthy section from infant Cyril’s point of view.  Perhaps, after all, this Ph.D. is not worth my while . . . The world inhabited by my subjects still seems bright and seductive, and the subjects themselves—the Brownings and Harriet Hosmer and William Story and, above all, Mrs. Gaskell—are still alive to me. The more I know of them, the more I love them. But I couldn’t be further from them, here at my desk in the British Library . . . My research is laborious and rewarding: I am clawing at an enormous cliff face, hoping to tunnel through it, but the rock is unbreakable . . . The enormity of the task ahead—writing 100,000 words of pure, never-before-known knowledge—is off-putting, impossible, preferably avoidable.

Perhaps, after all, this Ph.D. is not worth my while . . . The world inhabited by my subjects still seems bright and seductive, and the subjects themselves—the Brownings and Harriet Hosmer and William Story and, above all, Mrs. Gaskell—are still alive to me. The more I know of them, the more I love them. But I couldn’t be further from them, here at my desk in the British Library . . . My research is laborious and rewarding: I am clawing at an enormous cliff face, hoping to tunnel through it, but the rock is unbreakable . . . The enormity of the task ahead—writing 100,000 words of pure, never-before-known knowledge—is off-putting, impossible, preferably avoidable. I don’t actually have a lot to say about Stevens’s book in particular. I more or less enjoyed it: it’s fine, if you’re into memoirs, which I am generally not. Stevens’s particular take on autobiography in this book strikes me as remarkably niche, which makes me wonder even more about how publishing works. How big can the audience be for a book about a (relatively obscure? I’d say so?) young person’s love life and academic difficulties and preoccupation with Elizabeth Gaskell? Perhaps it was

I don’t actually have a lot to say about Stevens’s book in particular. I more or less enjoyed it: it’s fine, if you’re into memoirs, which I am generally not. Stevens’s particular take on autobiography in this book strikes me as remarkably niche, which makes me wonder even more about how publishing works. How big can the audience be for a book about a (relatively obscure? I’d say so?) young person’s love life and academic difficulties and preoccupation with Elizabeth Gaskell? Perhaps it was