It has been a somewhat chaotic time in my classes since I last posted—not in the classes themselves, really, which have gone on much as usual, when they have actually met. But there have been a couple of unanticipated disruptions to the term, as a result of which it feels as if we are struggling to build up any momentum.

It has been a somewhat chaotic time in my classes since I last posted—not in the classes themselves, really, which have gone on much as usual, when they have actually met. But there have been a couple of unanticipated disruptions to the term, as a result of which it feels as if we are struggling to build up any momentum.

First, Queen Elizabeth died. I did not expect this to affect my class schedule at all, but when the day of her funeral was declared a provincial holiday, Dalhousie decided to follow suit, so all classes were cancelled that day. I was not in favor of this plan: it’s embarrassing enough that we still have a hereditary monarchy in the first place, and the university doesn’t close for every non-statutory holiday (we are business as usual on Easter Monday, for example). A lot of other folks still had to work that day, too. However, once the public schools were closing there were certainly pragmatic arguments for making parents’ lives easier, and although it was a pain having to revise course plans with so little notice, once I’d done that I decided just to embrace the extra day off.

When I announced the schedule changes for the “day of mourning,” I commented “Let’s just hope we don’t also have a hurricane!” Well, what do you know: Hurricane Fiona headed straight for us this past weekend, and classes are cancelled again today, as crews clean up the debris and work on restoring power. The storm was not as severe in Halifax as in other parts of the region, where it did really catastrophic damage. Other parts of the city also fared worse than we did in our particular corner, where there were lots of limbs and branches blown off and some trees sheared in two, but no huge trees or poles down. We lost power for about 38 hours; we got it back last night and then lost it again for a short time this afternoon, meaning we are definitely not taking it for granted! Our freezer packs did a decent job keeping the food in the fridge chilled, and luckily the freezer itself wasn’t packed and what was in it stayed pretty much frozen solid. We have a small camp stove we use to boil water and do a bit of cooking as needed. Increasingly, folks around us have generators, and more than one neighbor kindly offered us whatever help we needed; if the outage had gone on much longer, we would have taken them up on it gratefully.

When I announced the schedule changes for the “day of mourning,” I commented “Let’s just hope we don’t also have a hurricane!” Well, what do you know: Hurricane Fiona headed straight for us this past weekend, and classes are cancelled again today, as crews clean up the debris and work on restoring power. The storm was not as severe in Halifax as in other parts of the region, where it did really catastrophic damage. Other parts of the city also fared worse than we did in our particular corner, where there were lots of limbs and branches blown off and some trees sheared in two, but no huge trees or poles down. We lost power for about 38 hours; we got it back last night and then lost it again for a short time this afternoon, meaning we are definitely not taking it for granted! Our freezer packs did a decent job keeping the food in the fridge chilled, and luckily the freezer itself wasn’t packed and what was in it stayed pretty much frozen solid. We have a small camp stove we use to boil water and do a bit of cooking as needed. Increasingly, folks around us have generators, and more than one neighbor kindly offered us whatever help we needed; if the outage had gone on much longer, we would have taken them up on it gratefully.

Assuming we are back on Wednesday, that will actually be our only day of classes this week, as Friday is another day off, although this time deliberately so, in recognition of National Truth & Reconciliation Day.

In between these disruptions, we have actually met a few times and I think it has gone basically fine. The energy seems a bit low to me in 19th-Century Fiction, although I blame it partly on our dreary windowless room, and it’s also possible that it seems that way to me because I can’t see students’ faces. I’ve been encouraging them to nod at me the way Wemmick nods at the Aged:

In between these disruptions, we have actually met a few times and I think it has gone basically fine. The energy seems a bit low to me in 19th-Century Fiction, although I blame it partly on our dreary windowless room, and it’s also possible that it seems that way to me because I can’t see students’ faces. I’ve been encouraging them to nod at me the way Wemmick nods at the Aged:

“Here’s Mr. Pip, aged parent,” said Wemmick, “and I wish you could hear his name. Nod away at him, Mr. Pip; that’s what he likes. Nod away at him, if you please, like winking!”

“This is a fine place of my son’s, sir,” cried the old man, while I nodded as hard as I possibly could. “This is a pretty pleasure-ground, sir. This spot and these beautiful works upon it ought to be kept together by the Nation, after my son’s time, for the people’s enjoyment.”

“You’re as proud of it as Punch; ain’t you, Aged?” said Wemmick, contemplating the old man, with his hard face really softened; “there’s a nod for you;” giving him a tremendous one; “there’s another for you;” giving him a still more tremendous one; “you like that, don’t you? If you’re not tired, Mr. Pip—though I know it’s tiring to strangers—will you tip him one more? You can’t think how it pleases him.”

I tipped him several more, and he was in great spirits.

I have wondered if stretching out our time on each book (which I did because of the advice we keep getting to ease up on students because of, well, everything) might be backfiring, because we’ve been talking about the same book for so long now. On the other hand, my competing fear is that a lot of them are quite behind in the reading, which could suggest I’m not allowing enough time. Well, we’ll be done with Great Expectations this week, one way or another, and next week we start Lady Audley’s Secret, which (if previous years are any indication) will perk them up, with its lurid and fast-moving plot and utter lack of subtlety (albeit it plenty of ambiguity, some of it, IMHO, evidence of authorial ineptness, not artistic complexity). (I do enjoy the novel a lot, and wrote an appreciation of it years ago for Open Letters Monthly.)

We’ve finished with Agatha Christie already in Mystery & Detective Fiction. I used to allot two class hours to Miss Marple stories, but for all Christie’s significance to the genre, I honestly don’t find there’s all that much to say about them, so I don’t regret having trimmed away one of those hours this year. We had a good student presentation on her, which gave us a productive second round of discussion. On Friday we had our first hour on Nancy Drew; we’re losing an hour on her to Fiona but will get another chance on Wednesday, with another student presentation. I always enjoy these so much: the students are so smart and creative and engaged, and they come up with such good ideas for class activities. Overall the energy in this seminar started off pretty good and seems to be getting better: spirits were high on Friday, partly because Nancy always proves very provocative. She’s just so good, and so good at everything: it’s annoying, I agree!

We’ve finished with Agatha Christie already in Mystery & Detective Fiction. I used to allot two class hours to Miss Marple stories, but for all Christie’s significance to the genre, I honestly don’t find there’s all that much to say about them, so I don’t regret having trimmed away one of those hours this year. We had a good student presentation on her, which gave us a productive second round of discussion. On Friday we had our first hour on Nancy Drew; we’re losing an hour on her to Fiona but will get another chance on Wednesday, with another student presentation. I always enjoy these so much: the students are so smart and creative and engaged, and they come up with such good ideas for class activities. Overall the energy in this seminar started off pretty good and seems to be getting better: spirits were high on Friday, partly because Nancy always proves very provocative. She’s just so good, and so good at everything: it’s annoying, I agree!

Personally, I continue to feel somewhat disoriented and unfocused, and I’m struggling to find my rhythm and pace in the classroom, especially (to my surprise, as it has long been my favorite lecture course) in 19th-Century Fiction. I don’t think (I certainly hope!) that this wavering isn’t evident to my students—that as far as they can tell, I’ve got my head in the game. I did mention to my seminar, in the context of one confusion I fell into, that (without going into details) I wasn’t as on top of things this term as I usually expect to be and that they should just ask or set me straight if they notice me getting something wrong. These recent cancellations and the last-minute changes they have required to my carefully laid plans are not helping: I don’t enjoy uncertainty at the best of times, which these definitely are not. Here’s hoping that once Fiona is well behind us, we don’t get any more unpleasant surprises for a while.

My classes have been meeting for a week now, and I said I was going to try to get back in the habit of reflecting on them, so here I am, although to be honest I find myself at something of a loss about what to say. Should I just focus on the classroom time, on what we’re reading and talking about, as if it’s just another year? Or should I try to explain how surreal it feels to be in the classroom, talking about our readings as if it’s just another year, and then, when the time is up, to be back in the strange disordered world of grief?

My classes have been meeting for a week now, and I said I was going to try to get back in the habit of reflecting on them, so here I am, although to be honest I find myself at something of a loss about what to say. Should I just focus on the classroom time, on what we’re reading and talking about, as if it’s just another year? Or should I try to explain how surreal it feels to be in the classroom, talking about our readings as if it’s just another year, and then, when the time is up, to be back in the strange disordered world of grief?

In Women and Detective Fiction I also began with some broad overviews, of detective fiction as a genre and of some of the questions that organize the course and will frame our readings. For last class we read a handful of “classic” stories to serve as touchstones for the resisting or subversive versions to come: “The Purloined Letter,” “A Scandal in Bohemia,” and, as a sample of hard-boiled detection, Hammett’s “Death & Company,” which is one of his ‘Continental Op’ stories. These give us a good sense of the masculine milieu of so much classic detective fiction, of the habits and practices of their detectives, and of the reductive roles assigned to women, or assumed of the women, in them. Today, as a contrast, we discussed Baroness Orczy’s “The Woman in the Big Hat,” which is one of her stories about Lady Molly of Scotland Yard. It has a delightful “reveal”:

In Women and Detective Fiction I also began with some broad overviews, of detective fiction as a genre and of some of the questions that organize the course and will frame our readings. For last class we read a handful of “classic” stories to serve as touchstones for the resisting or subversive versions to come: “The Purloined Letter,” “A Scandal in Bohemia,” and, as a sample of hard-boiled detection, Hammett’s “Death & Company,” which is one of his ‘Continental Op’ stories. These give us a good sense of the masculine milieu of so much classic detective fiction, of the habits and practices of their detectives, and of the reductive roles assigned to women, or assumed of the women, in them. Today, as a contrast, we discussed Baroness Orczy’s “The Woman in the Big Hat,” which is one of her stories about Lady Molly of Scotland Yard. It has a delightful “reveal”: We had already talked about Sherlock Holmes’s condescending remark, “You see, but you do not observe!” and now we could revisit it with observations about how gender affects what you see, or what you understand about what you see, and about kinds of expertise that are typically devalued because they are women’s and therefore considered trivial. This issue was also key to our other reading for today, Susan Glaspell’s “A Jury of Her Peers,” a wonderful story that highlights the way the law fails women, making justice something that can only be achieved by subverting it. We talked about the way Glaspell’s story, instead of offering up a big reveal at the end by the superior figure of the detective, instead allows the story to unfold gradually, the women’s dawning awareness drawing us along with them as our sympathies shift from the murdered man to the woman whose happiness he destroyed. Their solidarity grows partly in reaction to the men, who are lumbering around doing more typical (but, we easily see, entirely misguided) kinds of investigating. Every time they come in and make their jovially condescending remarks about “the ladies,” we too close ranks against them:

We had already talked about Sherlock Holmes’s condescending remark, “You see, but you do not observe!” and now we could revisit it with observations about how gender affects what you see, or what you understand about what you see, and about kinds of expertise that are typically devalued because they are women’s and therefore considered trivial. This issue was also key to our other reading for today, Susan Glaspell’s “A Jury of Her Peers,” a wonderful story that highlights the way the law fails women, making justice something that can only be achieved by subverting it. We talked about the way Glaspell’s story, instead of offering up a big reveal at the end by the superior figure of the detective, instead allows the story to unfold gradually, the women’s dawning awareness drawing us along with them as our sympathies shift from the murdered man to the woman whose happiness he destroyed. Their solidarity grows partly in reaction to the men, who are lumbering around doing more typical (but, we easily see, entirely misguided) kinds of investigating. Every time they come in and make their jovially condescending remarks about “the ladies,” we too close ranks against them: Other than the masks, nothing about teaching has changed, as far as I can tell, and in the moment I find I still enjoy the things I have always enjoyed about it: the material, the students, the dynamics and demands of discussion. I am relieved that (a few minor hiccups aside) I seem to staying on top of things in spite of being tired, distracted, and out of practice. When I’m not teaching, though, or busy with the other ever-proliferating work of the term, I feel more, not less, disoriented with the difference between the sameness of it all and my new changed reality. It’s a good thing, I know, that I am able to show up and be (more or less) my old self in the classroom, but at the same time I don’t know how to make sense of that or be at ease with it.

Other than the masks, nothing about teaching has changed, as far as I can tell, and in the moment I find I still enjoy the things I have always enjoyed about it: the material, the students, the dynamics and demands of discussion. I am relieved that (a few minor hiccups aside) I seem to staying on top of things in spite of being tired, distracted, and out of practice. When I’m not teaching, though, or busy with the other ever-proliferating work of the term, I feel more, not less, disoriented with the difference between the sameness of it all and my new changed reality. It’s a good thing, I know, that I am able to show up and be (more or less) my old self in the classroom, but at the same time I don’t know how to make sense of that or be at ease with it.

I’m in the little lull between the end of routine class work and the arrival of final essays and exams. Pre-COVID, this was a time for two ritual activities: cleaning my office and going Christmas shopping. Since I’m still working almost entirely at home, the first of these is mostly, if not entirely, beside the point: my current workspace, set up in what was once my son’s bedroom (and still furnished for that purpose, including his 20-year-old mate’s bed), could use a bit of tidying, but because online teaching means there’s a lot less physical debris from the term’s work, it’s not particularly chaotic. I’ll take the teaching-related books and folders to campus for storage when my courses are well and truly wrapped up – and bring home more books related to my sabbatical projects – but there won’t be any major housekeeping to do here until I return to working full-time there.

I’m in the little lull between the end of routine class work and the arrival of final essays and exams. Pre-COVID, this was a time for two ritual activities: cleaning my office and going Christmas shopping. Since I’m still working almost entirely at home, the first of these is mostly, if not entirely, beside the point: my current workspace, set up in what was once my son’s bedroom (and still furnished for that purpose, including his 20-year-old mate’s bed), could use a bit of tidying, but because online teaching means there’s a lot less physical debris from the term’s work, it’s not particularly chaotic. I’ll take the teaching-related books and folders to campus for storage when my courses are well and truly wrapped up – and bring home more books related to my sabbatical projects – but there won’t be any major housekeeping to do here until I return to working full-time there.

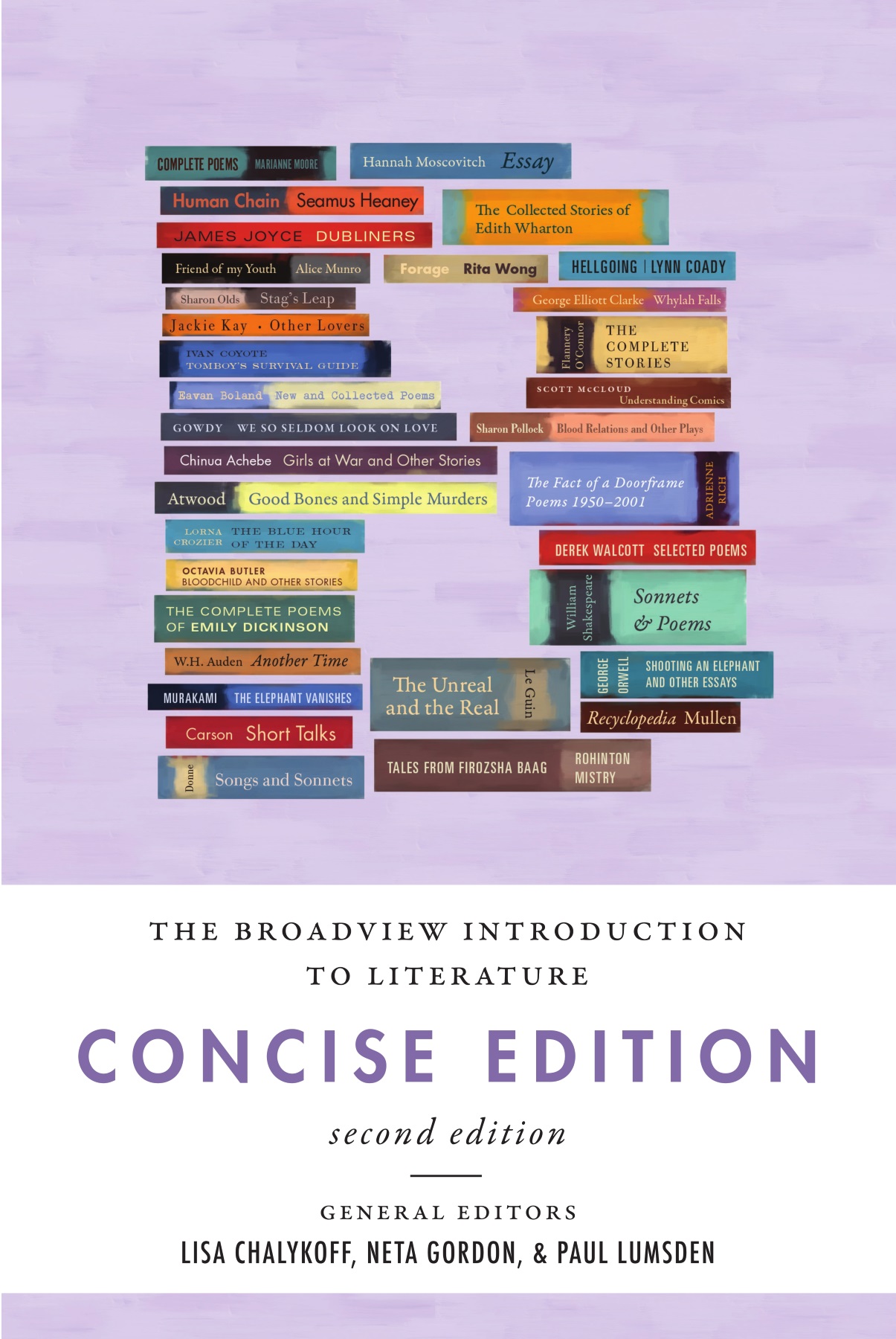

So what have I been doing instead of cleaning and shopping? Honestly, I’m not entirely sure where the “extra” time has gone. One factor, I think, is that online teaching actually doesn’t end neatly the way in-person classes do, or at least my classes haven’t: there has been a fair amount of tidying-up stuff to do, especially record-keeping and wrangling problems of one kind or another. One thing I suppose I didn’t have to do but considered worthwhile was an audit of students’ course bundles for English 1015 (where I am, again, using

So what have I been doing instead of cleaning and shopping? Honestly, I’m not entirely sure where the “extra” time has gone. One factor, I think, is that online teaching actually doesn’t end neatly the way in-person classes do, or at least my classes haven’t: there has been a fair amount of tidying-up stuff to do, especially record-keeping and wrangling problems of one kind or another. One thing I suppose I didn’t have to do but considered worthwhile was an audit of students’ course bundles for English 1015 (where I am, again, using

Next fall! Yes, because much to my immense relief and gratitude I am on sabbatical this winter term. This means – although nothing seems absolutely certain about the future anymore – that this term may have been my last term of online teaching. Please let that be true! This is not to say that I’ve hated everything about it. There are some aspects of it I have grown to like, and others that I have learned the value of, whether I like them or not. I will probably never give an in-person quiz or exam again: the simplicity of arranging make-up tests is a gift, for one thing, and especially valuable as we are likely (I hope and expect) to be much more aware from now on of the importance of letting students stay home when they are sick. I also like online reading journals: I had used them in the past as a way of encouraging students to keep up with the reading and getting them to practice expressing ideas about it with low stakes, but then ‘upgrades’ to our LMS took away the journal function I had used and I gave it up. Now that I know how to set up one-on-one discussion boards in Brightspace, I can see keeping up some version of these, especially because Brightspace makes it pretty easy to keep the records.

Next fall! Yes, because much to my immense relief and gratitude I am on sabbatical this winter term. This means – although nothing seems absolutely certain about the future anymore – that this term may have been my last term of online teaching. Please let that be true! This is not to say that I’ve hated everything about it. There are some aspects of it I have grown to like, and others that I have learned the value of, whether I like them or not. I will probably never give an in-person quiz or exam again: the simplicity of arranging make-up tests is a gift, for one thing, and especially valuable as we are likely (I hope and expect) to be much more aware from now on of the importance of letting students stay home when they are sick. I also like online reading journals: I had used them in the past as a way of encouraging students to keep up with the reading and getting them to practice expressing ideas about it with low stakes, but then ‘upgrades’ to our LMS took away the journal function I had used and I gave it up. Now that I know how to set up one-on-one discussion boards in Brightspace, I can see keeping up some version of these, especially because Brightspace makes it pretty easy to keep the records. What else has been good about online teaching? Well, while I still greatly prefer the energy, intellectual stimulation, and good cheer of class discussions, I have been impressed at the level of commentary on the discussion boards, especially, this term, in my 19th-century fiction class. I was frustrated all term at how much of it went on at the very end of each module, which meant only rarely was there substantial back-and-forth among the students, but that logistical griping tended to subside when I read through the posts that had come in. I am certain that I “heard” from more students this way than I would have in the classroom: I have pretty good participation rates, and I work hard to make space for students who are shy or just slower to know what they want to say (by, for instance, requiring everyone to put their hand up and wait to be called on), but even so it is typically a minority of students present who actually contribute.

What else has been good about online teaching? Well, while I still greatly prefer the energy, intellectual stimulation, and good cheer of class discussions, I have been impressed at the level of commentary on the discussion boards, especially, this term, in my 19th-century fiction class. I was frustrated all term at how much of it went on at the very end of each module, which meant only rarely was there substantial back-and-forth among the students, but that logistical griping tended to subside when I read through the posts that had come in. I am certain that I “heard” from more students this way than I would have in the classroom: I have pretty good participation rates, and I work hard to make space for students who are shy or just slower to know what they want to say (by, for instance, requiring everyone to put their hand up and wait to be called on), but even so it is typically a minority of students present who actually contribute. The single thing I have missed the most in my online classes has been laughter. You can do a lot of things asynchronously, and honestly I’m proud of the courses I offered. But

The single thing I have missed the most in my online classes has been laughter. You can do a lot of things asynchronously, and honestly I’m proud of the courses I offered. But

So what have my classes actually been about this week, then? Well, in my introduction to literature class, we have moved on from Module 1 (What words?) to Module 2 (Whose words?). The course overall is designed to keep complicating students’ engagement with the readings, so we start with the most basic (diction, connotation, denotation, etc.) and then add layers, this week some issues about voice, point of view, irony, and unreliability. Our readings feature speakers whose positions are worth interrogating: Tom Wayman’s “Did I Miss Anything?”, Aga Shahid Ali’s “The Wolf’s Postscript to ‘Little Red Riding Hood,'” and Browning’s “My Last Duchess.” (Our reader is the concise edition of Broadview’s Introduction to Literature, so all of our readings are chosen from their admirably varied selections.) Next week we move on to “About What? Subject and Theme.”

So what have my classes actually been about this week, then? Well, in my introduction to literature class, we have moved on from Module 1 (What words?) to Module 2 (Whose words?). The course overall is designed to keep complicating students’ engagement with the readings, so we start with the most basic (diction, connotation, denotation, etc.) and then add layers, this week some issues about voice, point of view, irony, and unreliability. Our readings feature speakers whose positions are worth interrogating: Tom Wayman’s “Did I Miss Anything?”, Aga Shahid Ali’s “The Wolf’s Postscript to ‘Little Red Riding Hood,'” and Browning’s “My Last Duchess.” (Our reader is the concise edition of Broadview’s Introduction to Literature, so all of our readings are chosen from their admirably varied selections.) Next week we move on to “About What? Subject and Theme.” In the 19th-century fiction class, which this term is the Austen to Dickens option, we are wrapping up our work on Persuasion, or we will be as more students get to the end of the module and submit their discussion posts. Anne Elliot can be a bit annoying in the first half of the novel, with her tendency to martyrdom and her inability to reach out and claim what she wants. I always find it interesting that so much of the novel’s resolution continues to be cautious, even reticent: this is not a novel celebrating impassioned outbursts, rebellion, or (to a point anyway) self-assertion. That will make Jane Eyre a dramatic contrast when we shift to Brontë’s novel next week, something I have been thinking about a lot because of course I can’t wait until Monday to start working on Jane Eyre but have to have my recorded lectures ready to go—which I do! I have discussed Jane Eyre with so many classes over the past 25 years that it hasn’t been hard to decide what the lectures should address, but it has been extremely hard to figure out how much they (I) should actually say. The model I have in mind is that they should include the equivalent of the opening comments I typically make in class, to set up the discussion to follow; explain any key critical or theoretical or historical contexts that I think are helpful to analyzing the novel well; and then prompt students to think about various elements of the novel in light of what I’ve said, rather than trying to cover what could be said about those elements. I pick some specific examples, but then I try to get out of the way, and then I show up in the online discussions to poke and provoke and steer as seems useful.

In the 19th-century fiction class, which this term is the Austen to Dickens option, we are wrapping up our work on Persuasion, or we will be as more students get to the end of the module and submit their discussion posts. Anne Elliot can be a bit annoying in the first half of the novel, with her tendency to martyrdom and her inability to reach out and claim what she wants. I always find it interesting that so much of the novel’s resolution continues to be cautious, even reticent: this is not a novel celebrating impassioned outbursts, rebellion, or (to a point anyway) self-assertion. That will make Jane Eyre a dramatic contrast when we shift to Brontë’s novel next week, something I have been thinking about a lot because of course I can’t wait until Monday to start working on Jane Eyre but have to have my recorded lectures ready to go—which I do! I have discussed Jane Eyre with so many classes over the past 25 years that it hasn’t been hard to decide what the lectures should address, but it has been extremely hard to figure out how much they (I) should actually say. The model I have in mind is that they should include the equivalent of the opening comments I typically make in class, to set up the discussion to follow; explain any key critical or theoretical or historical contexts that I think are helpful to analyzing the novel well; and then prompt students to think about various elements of the novel in light of what I’ve said, rather than trying to cover what could be said about those elements. I pick some specific examples, but then I try to get out of the way, and then I show up in the online discussions to poke and provoke and steer as seems useful. Oh dear: I’m back to logistics again! I do miss the simplicity of in-person teaching. In 2019-20, I had actually been working deliberately on weaning myself from more detailed lecture notes (not from lecture plans, just notes) and, trusting to my long experience, letting the discussion in class be more free-flowing. It was going well. I remember especially clearly the last class meeting for the Austen to Dickens class on March 13, 2020. We knew classes were going to be cancelled the next week, but we had a robust discussion of Mary Barton nonetheless and wrapped up not realizing that we would not meet again in person. I know that I could be back in person right now if I’d made that choice, but it would not have been a real return to that kind of ease and energy. I think I chose right, for me, for now, but that doesn’t make everything about this easy. I do still get the same satisfaction from engaging with students’ ideas and especially from being able to be present for them, albeit virtually. And on that note I guess I should go check on what new submissions are waiting for me!

Oh dear: I’m back to logistics again! I do miss the simplicity of in-person teaching. In 2019-20, I had actually been working deliberately on weaning myself from more detailed lecture notes (not from lecture plans, just notes) and, trusting to my long experience, letting the discussion in class be more free-flowing. It was going well. I remember especially clearly the last class meeting for the Austen to Dickens class on March 13, 2020. We knew classes were going to be cancelled the next week, but we had a robust discussion of Mary Barton nonetheless and wrapped up not realizing that we would not meet again in person. I know that I could be back in person right now if I’d made that choice, but it would not have been a real return to that kind of ease and energy. I think I chose right, for me, for now, but that doesn’t make everything about this easy. I do still get the same satisfaction from engaging with students’ ideas and especially from being able to be present for them, albeit virtually. And on that note I guess I should go check on what new submissions are waiting for me! Last year we were pretty much all online, in my department and across the university. This year, almost everybody else is back to teaching in person. Early in the planning process I had committed to doing my first-year course online. One reason was that it was such a big job planning and building it that I wanted to get more return on that investment. But it was also was the course that I least missed teaching in person. If our first-year classes were smaller, I might have felt differently, but teaching 120 students in a big auditorium, wearing a microphone, relying on PowerPoint, and knowing (and sometimes seeing) perfectly well that a lot of students in the room are only there because someone told them they had to be – that’s not a great experience, to be honest. I have always considered first-year teaching really important and I love engaging with the students who get excited about the material and the work – the ones who really show up for class (not just physically in class). It is especially gratifying when students taking intro primarily for their writing requirement discover a passion for analyzing literature and come back for more. Sometimes they even change their majors! But I don’t think lecture classes of 120 or more (however diligently you try to make them interactive, as of course I have always tried to do) are the right way to teach either literature or writing, and the crowd control aspects of it are always particularly disheartening. I also thought my online course went pretty well, all things considered. So why not do it that way again?

Last year we were pretty much all online, in my department and across the university. This year, almost everybody else is back to teaching in person. Early in the planning process I had committed to doing my first-year course online. One reason was that it was such a big job planning and building it that I wanted to get more return on that investment. But it was also was the course that I least missed teaching in person. If our first-year classes were smaller, I might have felt differently, but teaching 120 students in a big auditorium, wearing a microphone, relying on PowerPoint, and knowing (and sometimes seeing) perfectly well that a lot of students in the room are only there because someone told them they had to be – that’s not a great experience, to be honest. I have always considered first-year teaching really important and I love engaging with the students who get excited about the material and the work – the ones who really show up for class (not just physically in class). It is especially gratifying when students taking intro primarily for their writing requirement discover a passion for analyzing literature and come back for more. Sometimes they even change their majors! But I don’t think lecture classes of 120 or more (however diligently you try to make them interactive, as of course I have always tried to do) are the right way to teach either literature or writing, and the crowd control aspects of it are always particularly disheartening. I also thought my online course went pretty well, all things considered. So why not do it that way again? A couple of weeks later, Dalhousie did finally implement a vaccination requirement, along with mandatory masking for at least the month of September (neither of which was in place when I made up my mind to go online). I really hope that these measures and a generally high level of diligence help make it a safe and positive term for everyone now back on campus! For myself, though, while I do have regrets (anyone who has followed this blog knows how much I love being in the classroom), I appreciate the clarity of my situation and the continuity I can be sure of providing to my students. I don’t need to have multiple contingency plans – or to lecture masked or to dodge crowds in the hallways, or to work in my overheated office where at the moment I am not allowed to open the window. I do also feel that I am serving a need: there are students who themselves could not get back to Halifax, or who aren’t confident about returning to in-person classes, and I honestly think we should have tried harder to make sure they had more and less haphazard options given the predictable complications of this in-between phase, especially for international students.

A couple of weeks later, Dalhousie did finally implement a vaccination requirement, along with mandatory masking for at least the month of September (neither of which was in place when I made up my mind to go online). I really hope that these measures and a generally high level of diligence help make it a safe and positive term for everyone now back on campus! For myself, though, while I do have regrets (anyone who has followed this blog knows how much I love being in the classroom), I appreciate the clarity of my situation and the continuity I can be sure of providing to my students. I don’t need to have multiple contingency plans – or to lecture masked or to dodge crowds in the hallways, or to work in my overheated office where at the moment I am not allowed to open the window. I do also feel that I am serving a need: there are students who themselves could not get back to Halifax, or who aren’t confident about returning to in-person classes, and I honestly think we should have tried harder to make sure they had more and less haphazard options given the predictable complications of this in-between phase, especially for international students. Classes began here yesterday, and the discussion boards in my courses are now filling up with students introducing themselves and checking out how things are going to work. It’s not the same as meeting them face to face, but those of us who are online a lot one way or another know that you can communicate a lot about yourself through virtual interactions, and also that it is possible to create, sustain, and cherish real communities that way. I think the most important things I learned last year, which did involve a lot of trial and error, was that simpler is better and personal is best of all – not personal in the sense of over-sharing personal information, but personal meaning you bring yourself to the work, you show yourself in the work, and treat everybody involved as if they are people too. I’ve been trying to welcome each student individually to the class as they make their introductions: I don’t know if I’ll be able to keep this up as the pace of their contributions increases (there are 150 students all told across my two courses) but I want to make my presence felt from the beginning.

Classes began here yesterday, and the discussion boards in my courses are now filling up with students introducing themselves and checking out how things are going to work. It’s not the same as meeting them face to face, but those of us who are online a lot one way or another know that you can communicate a lot about yourself through virtual interactions, and also that it is possible to create, sustain, and cherish real communities that way. I think the most important things I learned last year, which did involve a lot of trial and error, was that simpler is better and personal is best of all – not personal in the sense of over-sharing personal information, but personal meaning you bring yourself to the work, you show yourself in the work, and treat everybody involved as if they are people too. I’ve been trying to welcome each student individually to the class as they make their introductions: I don’t know if I’ll be able to keep this up as the pace of their contributions increases (there are 150 students all told across my two courses) but I want to make my presence felt from the beginning. As for course content, well, the first week of Literature: How It Works focuses on the idea and practice of close reading, with an emphasis on word choices. This is how I always begin my introductory courses, so the only difference is delivery. Across the next few modules we just keep adding things to pay attention to (“stocking our critical toolbox”!) – all the while trying out our ideas through low-stakes writing. I’m using specifications grading again, simplified and clarified (I hope) from last year’s version. In Austen to Dickens we warm up (again, as always) with a bit of background on the history of the novel: nothing fancy, just a rough sketch to give some context for our actual readings. Next week we start on Persuasion. My favorite part of class prep last year was devising slide presentations in which I tried to capture not just the main talking points of what would have been our classroom discussions, but the spirit of them. I actually found – find – this work quite creative! I don’t do anything fancy, but I do try to have a kind of unfolding narrative, illustrated by apt graphics (and sometimes silly graphics, because I miss drawing stupid stick figures on the whiteboard). This year I’m going to be more explicit about the limitations of the lecture components, which are never (in person or online) meant to “cover” everything or answer every question. Last year some students expressed frustration that I raised questions in my lectures but didn’t go on to answer them: realizing that they had this expectation surprised me a bit, because my in-person lectures also can’t possibly answer every question that comes up, but I think the recorded delivery seems like it should maybe be more definitive or complete.

As for course content, well, the first week of Literature: How It Works focuses on the idea and practice of close reading, with an emphasis on word choices. This is how I always begin my introductory courses, so the only difference is delivery. Across the next few modules we just keep adding things to pay attention to (“stocking our critical toolbox”!) – all the while trying out our ideas through low-stakes writing. I’m using specifications grading again, simplified and clarified (I hope) from last year’s version. In Austen to Dickens we warm up (again, as always) with a bit of background on the history of the novel: nothing fancy, just a rough sketch to give some context for our actual readings. Next week we start on Persuasion. My favorite part of class prep last year was devising slide presentations in which I tried to capture not just the main talking points of what would have been our classroom discussions, but the spirit of them. I actually found – find – this work quite creative! I don’t do anything fancy, but I do try to have a kind of unfolding narrative, illustrated by apt graphics (and sometimes silly graphics, because I miss drawing stupid stick figures on the whiteboard). This year I’m going to be more explicit about the limitations of the lecture components, which are never (in person or online) meant to “cover” everything or answer every question. Last year some students expressed frustration that I raised questions in my lectures but didn’t go on to answer them: realizing that they had this expectation surprised me a bit, because my in-person lectures also can’t possibly answer every question that comes up, but I think the recorded delivery seems like it should maybe be more definitive or complete. As my ‘Victorian Woman Question’ seminar makes its way through The Mill on the Floss, I am very much missing the opportunity to engage in face to face discussion with everyone. It’s a novel that provokes delight, frustration, sorrow, and thought in so many ways–that raises so many complications for us, thematically and formally: it feels more difficult to choose topics and shape conversations for our online version of the class for The Mill on the Floss than it has felt for some of the other novels I have taught this way in the last few months, including (perhaps surprisingly) Middlemarch. But of course the novel itself is as wonderful as usual, and our readings for this past week included one of my favorite incidents: Mrs. Tulliver’s poignant attempt to hang on to her “chany.” It moved me even more this time: as the one-year anniversary of our COVID-inflicted isolation approaches, the things that connect us to each other and to our histories seem to me to be carrying more and more emotional weight. Here’s a post I wrote about Mrs. Tulliver’s “teraphim” almost a decade ago.

As my ‘Victorian Woman Question’ seminar makes its way through The Mill on the Floss, I am very much missing the opportunity to engage in face to face discussion with everyone. It’s a novel that provokes delight, frustration, sorrow, and thought in so many ways–that raises so many complications for us, thematically and formally: it feels more difficult to choose topics and shape conversations for our online version of the class for The Mill on the Floss than it has felt for some of the other novels I have taught this way in the last few months, including (perhaps surprisingly) Middlemarch. But of course the novel itself is as wonderful as usual, and our readings for this past week included one of my favorite incidents: Mrs. Tulliver’s poignant attempt to hang on to her “chany.” It moved me even more this time: as the one-year anniversary of our COVID-inflicted isolation approaches, the things that connect us to each other and to our histories seem to me to be carrying more and more emotional weight. Here’s a post I wrote about Mrs. Tulliver’s “teraphim” almost a decade ago. One of the many things that make reading George Eliot at once so challenging and so satisfying is her resistance to simplicity–especially moral simplicity. It’s difficult to sit in judgment on her characters. For one thing, she’s usually not just one but two or three steps ahead: she’s seen and analyzed their flaws with emphatic clarity, but she’s also put them in context, explaining their histories and causes and effects and pointing out to us that we aren’t really that different ourselves. Often the characters themselves are in conflict over their failings (think Bulstrode), and when they’re not, at least they can be shaken out of them temporarily, swept into the stream of the novel’s moral current (think Rosamond, or in a different way, Hetty). But these are the more grandiose examples, the ones we know we have to struggle to understand and embrace with our moral theories. Her novels also feature pettier and often more comically imperfect characters who are more ineffectual than damaging, or whose flaws turn out, under the right circumstances, to be strengths. In The Mill on the Floss, Mrs Glegg is a good example of someone who comes through in the end, the staunch family pride that makes her annoyingly funny early on ultimately putting her on the right side in the conflict that tears the novel apart.

One of the many things that make reading George Eliot at once so challenging and so satisfying is her resistance to simplicity–especially moral simplicity. It’s difficult to sit in judgment on her characters. For one thing, she’s usually not just one but two or three steps ahead: she’s seen and analyzed their flaws with emphatic clarity, but she’s also put them in context, explaining their histories and causes and effects and pointing out to us that we aren’t really that different ourselves. Often the characters themselves are in conflict over their failings (think Bulstrode), and when they’re not, at least they can be shaken out of them temporarily, swept into the stream of the novel’s moral current (think Rosamond, or in a different way, Hetty). But these are the more grandiose examples, the ones we know we have to struggle to understand and embrace with our moral theories. Her novels also feature pettier and often more comically imperfect characters who are more ineffectual than damaging, or whose flaws turn out, under the right circumstances, to be strengths. In The Mill on the Floss, Mrs Glegg is a good example of someone who comes through in the end, the staunch family pride that makes her annoyingly funny early on ultimately putting her on the right side in the conflict that tears the novel apart. Then there’s her sister Bessy, Mrs Tulliver, who is easy to dismiss as foolish and weak, but to whom I have become increasingly sympathetic over the years. Mrs Tulliver is foolish and weak, but in her own way she cleaves to the same values as the novel overall: family and memory, the “twining” of our affections “round those old inferior things.” In class tomorrow we are moving through Books III and IV, in which the Tulliver family fortunes collapse, along with Mr Tulliver himself, and the relatives gather to see what’s to be done. The way the prosperous sisters patronize poor Bessy is as devastatingly revealing about them as it is crushing to her hopes that they’ll pitch in to keep some of her household goods from being put up to auction:

Then there’s her sister Bessy, Mrs Tulliver, who is easy to dismiss as foolish and weak, but to whom I have become increasingly sympathetic over the years. Mrs Tulliver is foolish and weak, but in her own way she cleaves to the same values as the novel overall: family and memory, the “twining” of our affections “round those old inferior things.” In class tomorrow we are moving through Books III and IV, in which the Tulliver family fortunes collapse, along with Mr Tulliver himself, and the relatives gather to see what’s to be done. The way the prosperous sisters patronize poor Bessy is as devastatingly revealing about them as it is crushing to her hopes that they’ll pitch in to keep some of her household goods from being put up to auction: Early in these scenes Maggie finds that her mother’s “reproaches against her father…neutralized all her pity for griefs about table-cloths and china”; the aunts and uncles are pitiless in their indifference to Bessy’s misplaced priorities. I used to find her pathetic clinging to these domestic trifles in the face of much graver difficulties just more evidence that she belonged to the “narrow, ugly, grovelling existence, which even calamity does not elevate”–the environment that surrounds Tom and Maggie, but especially Maggie, with “oppressive narrowness,” with eventually catastrophic results. She also seemed a specimen of the kind of shallow-minded, materialistic woman George Eliot’s heroines aspire not to be. But she’s not really materialistic and shallow. She doesn’t want the teapot because it’s silver: she wants it because it’s tangible evidence of her ties to her past, of the choices and commitments and loves and hopes that have made up her life and identity. She’s not really mourning the loss of her “chany” and table linens; she’s mourning her severance from her history.

Early in these scenes Maggie finds that her mother’s “reproaches against her father…neutralized all her pity for griefs about table-cloths and china”; the aunts and uncles are pitiless in their indifference to Bessy’s misplaced priorities. I used to find her pathetic clinging to these domestic trifles in the face of much graver difficulties just more evidence that she belonged to the “narrow, ugly, grovelling existence, which even calamity does not elevate”–the environment that surrounds Tom and Maggie, but especially Maggie, with “oppressive narrowness,” with eventually catastrophic results. She also seemed a specimen of the kind of shallow-minded, materialistic woman George Eliot’s heroines aspire not to be. But she’s not really materialistic and shallow. She doesn’t want the teapot because it’s silver: she wants it because it’s tangible evidence of her ties to her past, of the choices and commitments and loves and hopes that have made up her life and identity. She’s not really mourning the loss of her “chany” and table linens; she’s mourning her severance from her history. I think I understand her better than I used to, and feel more tolerant of her bewildered grief, because I have “teraphim,” or “household gods,” of my own, things that I would grieve the loss of quite out of proportion to their actual value. They are things that tie me, too, to my history, as well as to memories of people in my life. I have a teapot, for instance, that was my grandmother’s; every time I use it, or the small array of cups and saucers and plates that remain from the same set (my grandmother was hard on her dishes!) I think of her and feel more like my old self. I have a pair of Denby mugs that were gifts from my parents many years ago, tributes to my childhood fascination with English history: one has Hampton Court on it, the other, the Tower–these, too, have become talismanic, having survived multiple moves. If I dropped one, I’d be devastated, and not just because as far as we’ve ever been able to find out, they would be impossible to replace. “Very commonplace, even ugly, that furniture of our early home might look if it were put up to auction,” remarks the narrator with typical prescience, shortly before financial calamity hits the Tullivers, but there’s no special merit in “striving after something better and better” at the expense of “the loves and sanctities of our life,” with their “deep immovable roots in memory.” Sometimes a teapot is not just a teapot.

I think I understand her better than I used to, and feel more tolerant of her bewildered grief, because I have “teraphim,” or “household gods,” of my own, things that I would grieve the loss of quite out of proportion to their actual value. They are things that tie me, too, to my history, as well as to memories of people in my life. I have a teapot, for instance, that was my grandmother’s; every time I use it, or the small array of cups and saucers and plates that remain from the same set (my grandmother was hard on her dishes!) I think of her and feel more like my old self. I have a pair of Denby mugs that were gifts from my parents many years ago, tributes to my childhood fascination with English history: one has Hampton Court on it, the other, the Tower–these, too, have become talismanic, having survived multiple moves. If I dropped one, I’d be devastated, and not just because as far as we’ve ever been able to find out, they would be impossible to replace. “Very commonplace, even ugly, that furniture of our early home might look if it were put up to auction,” remarks the narrator with typical prescience, shortly before financial calamity hits the Tullivers, but there’s no special merit in “striving after something better and better” at the expense of “the loves and sanctities of our life,” with their “deep immovable roots in memory.” Sometimes a teapot is not just a teapot. I miss writing my regular updates about what we’re doing in my classes. Given that I am still teaching, and covering much the same material as usual, I have been puzzling over why it nonetheless feels nearly impossible to talk about it right now–not the process or the logistics of it, which I have written about several times now, but the substance of it. So much is the same, even though we’re online, after all: as I’ve pointed out more than once to my students, we always read the books outside of the classroom, and we always did at least some of our work on them in writing, including sometimes reading journals or discussion boards much like what I’ve asked them to do for the online versions. Why is it that without the actual classroom time, I can’t figure out what to say about the weekly experience of my classes?

I miss writing my regular updates about what we’re doing in my classes. Given that I am still teaching, and covering much the same material as usual, I have been puzzling over why it nonetheless feels nearly impossible to talk about it right now–not the process or the logistics of it, which I have written about several times now, but the substance of it. So much is the same, even though we’re online, after all: as I’ve pointed out more than once to my students, we always read the books outside of the classroom, and we always did at least some of our work on them in writing, including sometimes reading journals or discussion boards much like what I’ve asked them to do for the online versions. Why is it that without the actual classroom time, I can’t figure out what to say about the weekly experience of my classes? The other thing that muddles me up about reporting on ‘this week’ is that most weeks I am actually focused on next week in my classes, as I need to get the lectures composed and recorded, the discussion prompts up (when they are my job), the quizzes made up and created in the tedious quiz tool with its endless drop-down menus — everything needs to be ready to go ahead of time, so that when the module begins they actually can do it at their own pace, as the asynchronous model promises. Again, this is very different from a regular term, in which preparations for lectures, assessments, and activities are often done close to (sometimes too close to!) the specific hour in which I’m going to use them. This lets me shape them to our current discussions, and it keeps me mentally right in the moment. Today, though, as an example of what’s different, for Mystery and Detective Fiction I will be creating a lecture about “Chasing Meaning in The Maltese Falcon,” while my students work through materials on The Murder of Roger Ackroyd – which I completed almost two weeks ago. (Notice I say “for” this class, not “in” this class, and that’s the key to the difference!) For The Victorian ‘Woman Question’ I just made my slides for next week, our last week on The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, and I already made my slides introducing The Mill on the Floss for the week after that. My mind is all over the place, not here, now, in this week.

The other thing that muddles me up about reporting on ‘this week’ is that most weeks I am actually focused on next week in my classes, as I need to get the lectures composed and recorded, the discussion prompts up (when they are my job), the quizzes made up and created in the tedious quiz tool with its endless drop-down menus — everything needs to be ready to go ahead of time, so that when the module begins they actually can do it at their own pace, as the asynchronous model promises. Again, this is very different from a regular term, in which preparations for lectures, assessments, and activities are often done close to (sometimes too close to!) the specific hour in which I’m going to use them. This lets me shape them to our current discussions, and it keeps me mentally right in the moment. Today, though, as an example of what’s different, for Mystery and Detective Fiction I will be creating a lecture about “Chasing Meaning in The Maltese Falcon,” while my students work through materials on The Murder of Roger Ackroyd – which I completed almost two weeks ago. (Notice I say “for” this class, not “in” this class, and that’s the key to the difference!) For The Victorian ‘Woman Question’ I just made my slides for next week, our last week on The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, and I already made my slides introducing The Mill on the Floss for the week after that. My mind is all over the place, not here, now, in this week. I will spend two hours this week with my students, if not in my classes: Thursday mornings I meet for an online but real-time discussion with the students who are taking The Victorian ‘Woman Question’ cross-listed as a graduate seminar, talking about the novel and also about some secondary readings. Then Thursday afternoon I’m having a drop-in office hour, which I’m pitching as a chance to ask questions about the courses or just to come and hang out for a while. I floated the idea of having some actual real-time class discussion, but scheduling presented a lot of obstacles and students’ reluctance to be recorded (so as not to disadvantage those who couldn’t attend) also proved, understandably, another disincentive. So we won’t dig into questions about our reading except, perhaps, incidentally, but at least we can see each other’s faces and infuse a little shared time into the otherwise radically dispersed experience of this online semester–hopefully, possibly, maybe our last one. Also, maybe, hopefully, possibly, we’ll get nice enough weather in April, before this term is over, that we can try holding that drop-in office hour somewhere outside, near enough to see each other’s faces if still distant enough not to put each other at risk.

I will spend two hours this week with my students, if not in my classes: Thursday mornings I meet for an online but real-time discussion with the students who are taking The Victorian ‘Woman Question’ cross-listed as a graduate seminar, talking about the novel and also about some secondary readings. Then Thursday afternoon I’m having a drop-in office hour, which I’m pitching as a chance to ask questions about the courses or just to come and hang out for a while. I floated the idea of having some actual real-time class discussion, but scheduling presented a lot of obstacles and students’ reluctance to be recorded (so as not to disadvantage those who couldn’t attend) also proved, understandably, another disincentive. So we won’t dig into questions about our reading except, perhaps, incidentally, but at least we can see each other’s faces and infuse a little shared time into the otherwise radically dispersed experience of this online semester–hopefully, possibly, maybe our last one. Also, maybe, hopefully, possibly, we’ll get nice enough weather in April, before this term is over, that we can try holding that drop-in office hour somewhere outside, near enough to see each other’s faces if still distant enough not to put each other at risk.

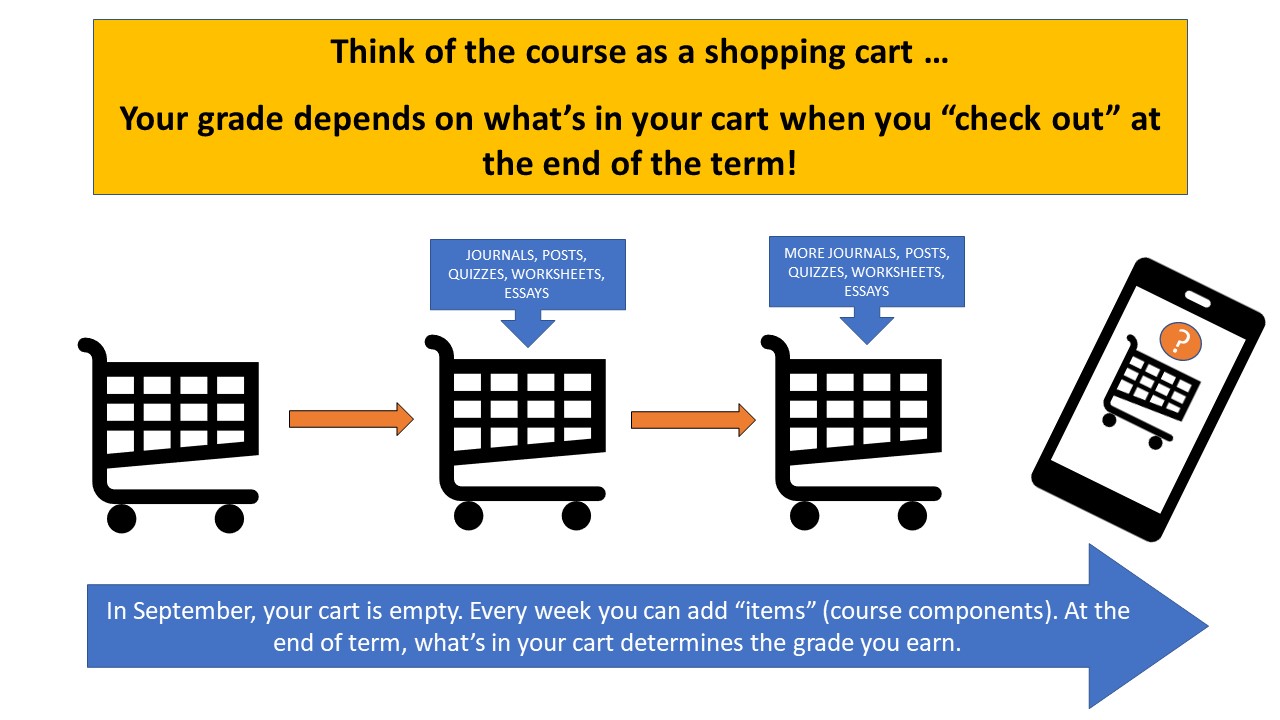

As if converting my courses to online versions wasn’t challenging enough, I also used specifications grading for the first time this fall, for my first-year class “Literature: How It Works.” This is an experiment I had been thinking a lot about before the pandemic struck: in fact, on March 13, the last day we were all on campus, I actually had a meeting with our Associate Dean to discuss how to make sure doing so wouldn’t conflict with any of the university’s or faculty’s policies. Though I did have some second thoughts after the “pivot” to online teaching, it seemed to me that many features of specifications grading were well suited to Brightspace-based delivery, so I decided to persist with the plan, and I spent a great deal of time and thought over the summer figuring out my version of it.

As if converting my courses to online versions wasn’t challenging enough, I also used specifications grading for the first time this fall, for my first-year class “Literature: How It Works.” This is an experiment I had been thinking a lot about before the pandemic struck: in fact, on March 13, the last day we were all on campus, I actually had a meeting with our Associate Dean to discuss how to make sure doing so wouldn’t conflict with any of the university’s or faculty’s policies. Though I did have some second thoughts after the “pivot” to online teaching, it seemed to me that many features of specifications grading were well suited to Brightspace-based delivery, so I decided to persist with the plan, and I spent a great deal of time and thought over the summer figuring out my version of it. I won’t go into every detail of the plan I finally came up with (though if anyone is really keen to see the extensive documentation, I’d be happy to share it by email). Basically, I made a list of the kinds of work I wanted students to do in service of the course’s multiple objectives: reading journals, discussion posts and replies, writing worksheets, quizzes, and essays. Then I worked out what seemed to me reasonable quantities of each component for bundles I called PASS, CORE, MORE, and MOST. These bundles corresponded to D, C, B, and A grades at the end of term; students’ grades on the final exam determined if they got a + or – added to their letter grade. I also (and in many ways this is the most important part of the whole system!) drew up the specifications for what would count as satisfactory work of each kind: completing a bundle didn’t mean just turning in enough components but turning in enough that met the specifications. Following the lead of others who have used this kind of system, I tried to make the specifications equivalent to something more like a typical B than a bare pass.

I won’t go into every detail of the plan I finally came up with (though if anyone is really keen to see the extensive documentation, I’d be happy to share it by email). Basically, I made a list of the kinds of work I wanted students to do in service of the course’s multiple objectives: reading journals, discussion posts and replies, writing worksheets, quizzes, and essays. Then I worked out what seemed to me reasonable quantities of each component for bundles I called PASS, CORE, MORE, and MOST. These bundles corresponded to D, C, B, and A grades at the end of term; students’ grades on the final exam determined if they got a + or – added to their letter grade. I also (and in many ways this is the most important part of the whole system!) drew up the specifications for what would count as satisfactory work of each kind: completing a bundle didn’t mean just turning in enough components but turning in enough that met the specifications. Following the lead of others who have used this kind of system, I tried to make the specifications equivalent to something more like a typical B than a bare pass. To start with, then, what seemed to go well? First, especially when it came time to assess the students’ longer essays, I really appreciated being freed from assigning them letter grades. Almost every single essay submitted (so, nearly 180 assignments over the term) clearly met the specifications for the assignment, so our focus could be on giving feedback, not (consciously or unconsciously) trying to justify minute gradations in our assessments. I hadn’t realized just how much it weighed on me needing to make artificially precise distinctions between, say, B- and C+ papers, or trying to decide if an unsuccessful attempt at a more ambitious or original argument should really get the same grade as an immaculately polished version of one that mostly reiterated my lectures. Once I’d read through a submission to see if it met the specifications, I could go back and reread with an eye to engaging with it honestly and constructively. This is what I thought I did already, but if you haven’t ever tried grading essays without actually grading them, you too may be surprised at how liberating it feels to let go of that awareness that when you’re done, you have to put a particular pin in it.

To start with, then, what seemed to go well? First, especially when it came time to assess the students’ longer essays, I really appreciated being freed from assigning them letter grades. Almost every single essay submitted (so, nearly 180 assignments over the term) clearly met the specifications for the assignment, so our focus could be on giving feedback, not (consciously or unconsciously) trying to justify minute gradations in our assessments. I hadn’t realized just how much it weighed on me needing to make artificially precise distinctions between, say, B- and C+ papers, or trying to decide if an unsuccessful attempt at a more ambitious or original argument should really get the same grade as an immaculately polished version of one that mostly reiterated my lectures. Once I’d read through a submission to see if it met the specifications, I could go back and reread with an eye to engaging with it honestly and constructively. This is what I thought I did already, but if you haven’t ever tried grading essays without actually grading them, you too may be surprised at how liberating it feels to let go of that awareness that when you’re done, you have to put a particular pin in it. On a related note, something else that I think was good (though it was a bit hard for me to tell without having a chance to talk it over with the class in person) was that the system gave students a fair amount of control over their final grade for the course. Instead of trying to meet some standard that–no matter how carefully you explain and model it–often seems obscure to students, especially in first-year (“what do you want?” is an ordinarily all-too-frequent question about their essay assignments) they could keep a tally of their satisfactory course components and know exactly what else they needed to do to complete a particular bundle and thus earn a particular grade. That didn’t mean it was an automatic process; again, to be rated satisfactory, the work had to meet the specifications I set. I tried to make the specifications concrete, though: they didn’t include any abstract qualitative standards (like “excellence” or “thoughtful”). The core standards were things like “on time,” “on topic,” “within the word limit,” and, most important, to my mind, “shows a good faith effort” to do the task at hand. I suppose that last one is open to interpretation, but I think it sends the right message to students trying to learn how to do something unfamiliar: if they actually try to do it, that counts. When my TA and I debated the occasional submission that had arguably missed the mark in some other way, we used “good faith effort” as the deciding factor for whether they earned the credit: we used it generously, rather than punitively.

On a related note, something else that I think was good (though it was a bit hard for me to tell without having a chance to talk it over with the class in person) was that the system gave students a fair amount of control over their final grade for the course. Instead of trying to meet some standard that–no matter how carefully you explain and model it–often seems obscure to students, especially in first-year (“what do you want?” is an ordinarily all-too-frequent question about their essay assignments) they could keep a tally of their satisfactory course components and know exactly what else they needed to do to complete a particular bundle and thus earn a particular grade. That didn’t mean it was an automatic process; again, to be rated satisfactory, the work had to meet the specifications I set. I tried to make the specifications concrete, though: they didn’t include any abstract qualitative standards (like “excellence” or “thoughtful”). The core standards were things like “on time,” “on topic,” “within the word limit,” and, most important, to my mind, “shows a good faith effort” to do the task at hand. I suppose that last one is open to interpretation, but I think it sends the right message to students trying to learn how to do something unfamiliar: if they actually try to do it, that counts. When my TA and I debated the occasional submission that had arguably missed the mark in some other way, we used “good faith effort” as the deciding factor for whether they earned the credit: we used it generously, rather than punitively. One other way I consider the experiment a success was that it seemed to me that the students’ quantity of work–their consistent effort over time–did ultimately lead to improvements in the quality of their work. The skepticism I faced from some colleagues when I mentioned this plan tended to focus on concerns about rewarding quantity over quality, or about not sufficiently recognizing and rewarding exceptional quality. Over the term I did sometimes worry about this myself: much as I liked being freed from grading individual assignments, I didn’t always like giving the same assessment of ‘satisfactory’ to assignments that ranged from perfunctory or barely passable at one end of the scale to impressively articulate and insightful at the other. You can signal the difference through your feedback, though, and that’s the big shift specifications grading requires. The other key point is that most people really do get better at writing if they practice (and get feedback, and engage with lots of examples of other people’s writing) and so making it a requirement for a good grade that you had to write a lot had the side-effect (or, met the course objective!) of helping a lot of students improve as writers. Between reading journals and discussion posts and replies, there was no way to get an A in this version of the course without writing a few hundred words every week, which is a lot more than students necessarily have to do in my face-to-face versions of intro classes. Especially in their final batch of essays, I think that practice showed.

One other way I consider the experiment a success was that it seemed to me that the students’ quantity of work–their consistent effort over time–did ultimately lead to improvements in the quality of their work. The skepticism I faced from some colleagues when I mentioned this plan tended to focus on concerns about rewarding quantity over quality, or about not sufficiently recognizing and rewarding exceptional quality. Over the term I did sometimes worry about this myself: much as I liked being freed from grading individual assignments, I didn’t always like giving the same assessment of ‘satisfactory’ to assignments that ranged from perfunctory or barely passable at one end of the scale to impressively articulate and insightful at the other. You can signal the difference through your feedback, though, and that’s the big shift specifications grading requires. The other key point is that most people really do get better at writing if they practice (and get feedback, and engage with lots of examples of other people’s writing) and so making it a requirement for a good grade that you had to write a lot had the side-effect (or, met the course objective!) of helping a lot of students improve as writers. Between reading journals and discussion posts and replies, there was no way to get an A in this version of the course without writing a few hundred words every week, which is a lot more than students necessarily have to do in my face-to-face versions of intro classes. Especially in their final batch of essays, I think that practice showed.