I had such good intentions to post regularly again this term about my classes . . . and somehow the first month has gone by and I’m only just getting around to it. The thing is (and I know I’ve said this a few times recently) there was a lot going on in my life besides classes in September, much of it difficult and distracting in one way or another—which is not meant as an excuse but as an explanation. Eventually, someday, maybe, my life won’t have quite so many, or at least quite such large, or quite such fraught, moving pieces. Honestly, I am exhausted by the ongoing instability—about which (as I have also said before) more details later, perhaps—and the constant effort it requires to keep my mental balance.

I had such good intentions to post regularly again this term about my classes . . . and somehow the first month has gone by and I’m only just getting around to it. The thing is (and I know I’ve said this a few times recently) there was a lot going on in my life besides classes in September, much of it difficult and distracting in one way or another—which is not meant as an excuse but as an explanation. Eventually, someday, maybe, my life won’t have quite so many, or at least quite such large, or quite such fraught, moving pieces. Honestly, I am exhausted by the ongoing instability—about which (as I have also said before) more details later, perhaps—and the constant effort it requires to keep my mental balance.

Anyway! Yes, I’m back in class, and that has actually been a stabilizing influence overall: it turns out I do better when I am busier. I have two courses this term. One is a section of “Literature: How It Works,” one of our suite of first-year offerings that do double-duty as introductions to the study of literature and writing requirement classes. In the nearly 30 years I’ve been teaching at Dalhousie, I’ve offered an intro class pretty much every year, though multiple revisions of our curriculum over that same long period have changed their names, descriptions, formats, and especially sizes. I don’t think it’s just nostalgia that makes me look back wistfully on the version that was standard in my first years here: called “Introduction to Literature,” running all year, capped at 55 with one teaching assistant per section to keep us in line with the 30:1 ratio required by the writing requirement regulations. So many things about that arrangement were preferable to the current half-year version with 90 students . . . but even as demand has stayed robust for these classes, our available resources have shrunk, and so here we are. (Oh, but how much more I could do when I didn’t lose so much time to starting and stopping anew every term—and actually the change to half-year courses was brought about because the university acquired registration software that could not accommodate full-year courses and so we were forced to change our pedagogy to fit it. That still makes me angry!)

There are still things I like about teaching first-year classes, though, chief among them the element of surprise, for them as well as for me: because students mostly sign up for them to fulfill a requirement, and choose a section based on their timetable, not the reading list, they often have low expectations (or none at all) for my class in particular, meaning if something lights them up, it’s kind of a bonus for them; and for me, it’s a rare opportunity to have a room full of students from across a wide range of the university’s programs who bring a lot of different perspectives and voices to the class. I do my best to keep a positive and personal atmosphere—and some interactive aspects—even in a tiered lecture hall that makes it essential for me to use PowerPoint and wear a microphone; we have weekly smaller tutorials that also give us a chance to know each other better.

There are still things I like about teaching first-year classes, though, chief among them the element of surprise, for them as well as for me: because students mostly sign up for them to fulfill a requirement, and choose a section based on their timetable, not the reading list, they often have low expectations (or none at all) for my class in particular, meaning if something lights them up, it’s kind of a bonus for them; and for me, it’s a rare opportunity to have a room full of students from across a wide range of the university’s programs who bring a lot of different perspectives and voices to the class. I do my best to keep a positive and personal atmosphere—and some interactive aspects—even in a tiered lecture hall that makes it essential for me to use PowerPoint and wear a microphone; we have weekly smaller tutorials that also give us a chance to know each other better.

I continue to think a lot in my first-year teaching about the issues of products and processes that I have written about here before. This year I am also using specifications grading again, with its emphasis on practice and feedback rather than polish and judgment. I feel good about the basic structure of the course I have worked out over its recent iterations—but it seems possible I will get a break from teaching intro next year, and that would buy me time to give it a refresh, perhaps (who knows) the last one before I retire. This week is the last one of our initial unit on poetry (we will return to some more complex poems at the end of term). We’ve approached it in steps, focusing first on diction, then on point of view and voice, then on figurative language, then subject and theme—all, as I’ve tried to emphasize, artificially separated so that we can be clear about what they are and how to talk about them, but actually happening and mattering all at once. So this week’s lecture is “Poetry: The Whole Package” and the reading is “Dover Beach”—last year it was “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” but that seemed to be too much for most of them, and no wonder. (Still, it was fun to teach “Prufrock,” which I’m not sure I’d done before.)

My other class is 19thC Fiction, this time around the Dickens to Hardy version. (Speaking of full-year classes, once upon a time I got to teach a full year honours seminar in the 19th-century British novel and let me tell you we did some real reading in that class! Ah, those were the days.) (Is talking like this a sign that I should be thinking more seriously about retirement?) I went with “troublesome women” as my unifying theme this time: Bleak House, Adam Bede, Lady Audley’s Secret, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. We have been making our way through Bleak House all month; Wednesday is our final session on it, and I am really looking forward to it. I hope the students are too! But I’m also already getting excited about moving on to Adam Bede, which I have not taught since 2017. It was wonderful to hear a number of students say that they were keen to read Bleak House because, often against their own expectations, they had really loved studying David Copperfield with me last year in the Austen to Dickens course. (You see, this is why we need breadth requirements in our programs: how can you be sure what you are interested in, or might even love, if you aren’t pushed to try a lot of different things? And of course even if you don’t love something you try, at least now you know more about it than whatever you assumed about it before.)

My other class is 19thC Fiction, this time around the Dickens to Hardy version. (Speaking of full-year classes, once upon a time I got to teach a full year honours seminar in the 19th-century British novel and let me tell you we did some real reading in that class! Ah, those were the days.) (Is talking like this a sign that I should be thinking more seriously about retirement?) I went with “troublesome women” as my unifying theme this time: Bleak House, Adam Bede, Lady Audley’s Secret, and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. We have been making our way through Bleak House all month; Wednesday is our final session on it, and I am really looking forward to it. I hope the students are too! But I’m also already getting excited about moving on to Adam Bede, which I have not taught since 2017. It was wonderful to hear a number of students say that they were keen to read Bleak House because, often against their own expectations, they had really loved studying David Copperfield with me last year in the Austen to Dickens course. (You see, this is why we need breadth requirements in our programs: how can you be sure what you are interested in, or might even love, if you aren’t pushed to try a lot of different things? And of course even if you don’t love something you try, at least now you know more about it than whatever you assumed about it before.)

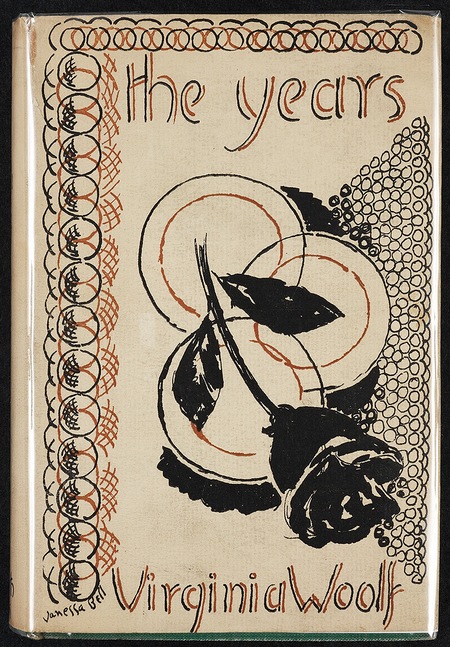

In many ways the first month of term is deceptively simple: things are heating up now, for us and for our students, as assignments begin to come due. After a fairly dreary summer, though, when the days often seemed to drag on and on, I appreciate how much faster the time passes when there’s a lot to do and I’m making myself useful (or so I hope) to other people. I also decided to put my name on the list for our departmental speaker series, to make sure the work I did over the summer didn’t go to waste, so I will wrap up this week by presenting my paper “‘Feeble Twaddle’: Failure, Form, and Purpose in Virginia Woolf’s The Years.” Wish me luck! It has been a long time since I did this exact thing; in fact, I believe the last presentation I made to my colleagues was about academic blogging, more than a decade ago. I have given conference papers and other public presentations since then: I haven’t just been talking to myself—and you—here, I promise! But I haven’t felt that I was doing work that fit very well into this series, which for related reasons I haven’t attended regularly for many years. I made a vow to engage more with my department and my colleagues this year, though, and so I’m going to the talks as well as giving my own. This is one result of my recent reflections on what I want this last stage of my professional life to be like: difficult as it still sometimes is for me to do this, I want to be present for it, if that makes any sense.

In many ways the first month of term is deceptively simple: things are heating up now, for us and for our students, as assignments begin to come due. After a fairly dreary summer, though, when the days often seemed to drag on and on, I appreciate how much faster the time passes when there’s a lot to do and I’m making myself useful (or so I hope) to other people. I also decided to put my name on the list for our departmental speaker series, to make sure the work I did over the summer didn’t go to waste, so I will wrap up this week by presenting my paper “‘Feeble Twaddle’: Failure, Form, and Purpose in Virginia Woolf’s The Years.” Wish me luck! It has been a long time since I did this exact thing; in fact, I believe the last presentation I made to my colleagues was about academic blogging, more than a decade ago. I have given conference papers and other public presentations since then: I haven’t just been talking to myself—and you—here, I promise! But I haven’t felt that I was doing work that fit very well into this series, which for related reasons I haven’t attended regularly for many years. I made a vow to engage more with my department and my colleagues this year, though, and so I’m going to the talks as well as giving my own. This is one result of my recent reflections on what I want this last stage of my professional life to be like: difficult as it still sometimes is for me to do this, I want to be present for it, if that makes any sense.

And that’s where things are at the moment, after the first month back in my classes. I probably shouldn’t make any promises about returning to the kind of regular updates I used to make to this series, but as always, I have found the exercise of writing this stuff up both fun and helpful—that hasn’t changed since I reflected on my first year of blogging my teaching. It’s a bit like exercise, I guess: if you can just get past the inertia, you feel better for doing it! We’ll see if that’s motivation enough.

This term is the first one since I began posting about ‘this week in my classes’ in 2007 that I haven’t posted at all about my classes. What’s up with that, you might wonder? Well, more likely you hadn’t noticed or wondered, but I’ve certainly been aware of it and pondering what, if anything, to do about it.

This term is the first one since I began posting about ‘this week in my classes’ in 2007 that I haven’t posted at all about my classes. What’s up with that, you might wonder? Well, more likely you hadn’t noticed or wondered, but I’ve certainly been aware of it and pondering what, if anything, to do about it. It certainly isn’t anything to do with this term’s classes. At least from my perspective, both of them—Mystery & Detective Fiction and The Victorian ‘Woman Question’—have gone very well. Of course there have been the occasional sessions that dragged a bit, and we had an unusually high number of snow days that created a lot of logistical headaches, but in general discussion was both substantive and lively. I continue to try to wean myself from my lecture notes. This gets easier and easier in the mystery class, as I am pretty confident now both about how I want to frame the course and readings in terms of ‘big picture’ issues and about the specific readings. (I mix in new options quite regularly, because for various reasons I have been teaching the course basically every year for ages, so this definitely keeps it fresh and interesting for me: I just finished reading Dorothy B. Hughes’s The Expendable Man and I’m 90% certain I’m putting it on the reading list for next year, for one!) The ‘woman question’ class is a seminar, so I don’t lecture there anyway; I so looked forward to our class meetings all term, both because the readings are all favorites of mine and because we always had such good conversations about them. The only slight exception was with the excerpts from Aurora Leigh, from which I learned both that assigning excerpts is a bad idea (something I already believed but overrode, for practical reasons)—when it comes to long texts, do or do not, there is no try!—and that narrative poetry is hard, or at least it takes a different kind of preparation and attention than fiction, and that if I’m going to assign any of Aurora Leigh I need to take that into account.

It certainly isn’t anything to do with this term’s classes. At least from my perspective, both of them—Mystery & Detective Fiction and The Victorian ‘Woman Question’—have gone very well. Of course there have been the occasional sessions that dragged a bit, and we had an unusually high number of snow days that created a lot of logistical headaches, but in general discussion was both substantive and lively. I continue to try to wean myself from my lecture notes. This gets easier and easier in the mystery class, as I am pretty confident now both about how I want to frame the course and readings in terms of ‘big picture’ issues and about the specific readings. (I mix in new options quite regularly, because for various reasons I have been teaching the course basically every year for ages, so this definitely keeps it fresh and interesting for me: I just finished reading Dorothy B. Hughes’s The Expendable Man and I’m 90% certain I’m putting it on the reading list for next year, for one!) The ‘woman question’ class is a seminar, so I don’t lecture there anyway; I so looked forward to our class meetings all term, both because the readings are all favorites of mine and because we always had such good conversations about them. The only slight exception was with the excerpts from Aurora Leigh, from which I learned both that assigning excerpts is a bad idea (something I already believed but overrode, for practical reasons)—when it comes to long texts, do or do not, there is no try!—and that narrative poetry is hard, or at least it takes a different kind of preparation and attention than fiction, and that if I’m going to assign any of Aurora Leigh I need to take that into account. So what’s my problem this term? I think it is rooted in my uncertainty about how to address some big changes that have taken place in my personal life. When I wrote up my

So what’s my problem this term? I think it is rooted in my uncertainty about how to address some big changes that have taken place in my personal life. When I wrote up my  In my current circumstances, this principle, if that’s what it is, runs up against the principle that I shouldn’t talk about other people’s business here: it feels wrong not to acknowledge that my life has changed significantly, but I have felt—rightly, I think—constrained from going into any detail that might cross the line, which has also meant I have felt constrained from talking about some of my recent reading as frankly and completely as I would have liked to, because I couldn’t address how something like, say, Maggie Smith’s

In my current circumstances, this principle, if that’s what it is, runs up against the principle that I shouldn’t talk about other people’s business here: it feels wrong not to acknowledge that my life has changed significantly, but I have felt—rightly, I think—constrained from going into any detail that might cross the line, which has also meant I have felt constrained from talking about some of my recent reading as frankly and completely as I would have liked to, because I couldn’t address how something like, say, Maggie Smith’s  Obviously I have reached a point at which it seems fine and reasonable to say what has been going on, though I don’t expect I will ever consider Novel Readings an appropriate place to talk about how or why things have unfolded in this way, or even how I feel about it all! That’s nobody’s business but ours, by which I mean mine and my (truly excellent) therapist’s. 😉 Seriously, though, I do believe we bring our whole selves to our reading, so what I want to work on is how to acknowledge how my new reality sometimes does affect my engagement with books. I can say already that nothing about Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce, which I just read for my book club, seems relevant or resonant at all in that way (though I did enjoy it on its own terms)—though there were moments in

Obviously I have reached a point at which it seems fine and reasonable to say what has been going on, though I don’t expect I will ever consider Novel Readings an appropriate place to talk about how or why things have unfolded in this way, or even how I feel about it all! That’s nobody’s business but ours, by which I mean mine and my (truly excellent) therapist’s. 😉 Seriously, though, I do believe we bring our whole selves to our reading, so what I want to work on is how to acknowledge how my new reality sometimes does affect my engagement with books. I can say already that nothing about Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce, which I just read for my book club, seems relevant or resonant at all in that way (though I did enjoy it on its own terms)—though there were moments in

I’ve always loved these lines from Tennyson’s The Princess:

I’ve always loved these lines from Tennyson’s The Princess: Actually, thinking about it now, maybe there are more moving parts than there used to be. Once upon a time we didn’t use an LMS, for example, and while there’s no doubt that Brightspace (formerly Blackboard formerly Web CT formerly DIY websites) is a useful back-up system for in-person courses—a storage facility available to your students 24/7 so they can never not locate their syllabus!—it’s also the case that expectations have gone up considerably around our use of them (and students’ reliance on them). Now I post my PPT slides on Brightspace after class, for example, something that requires multiple additional steps, assuming I remember to do it in the first place. (I never used to use PowerPoint, either, and I blame it and Brightspace, which both require incessant mousing, for my now chronic shoulder pain.) I used to give quizzes and midterms in class; now, they are all taken in Brightspace—but that too means many more steps than devising the questions and making copies, setting up all the many features just right and entering the questions in the optimal way. When we were all online, I posted weekly announcements for my classes: it turns out students really appreciated these, so I’ve kept doing them, but they take me (no kidding) hours to compose, both to make sure they are optimally clear and useful and because heaven forbid there’s a mistake in one, like a wrong deadline, that gets fixed in their minds or calendars in spite of any subsequent efforts to correct it! Recently, too, in a departmental discussion around class size and workload, one of my colleagues pointed out ruefully that “there didn’t used to be email” and that is such a good point, especially as our class sizes have gone up even as we became not just teachers but customer service representatives! (And yet somehow, without an LMS and without Outlook and without PowerPoint, we managed to do our jobs. Imagine that. Did we do a worse job? Maybe in some respects—accessibility seems like a key point here—but I really do wonder how much all of this apparatus actually helps, rather than hinders, us in our core mission.)

Actually, thinking about it now, maybe there are more moving parts than there used to be. Once upon a time we didn’t use an LMS, for example, and while there’s no doubt that Brightspace (formerly Blackboard formerly Web CT formerly DIY websites) is a useful back-up system for in-person courses—a storage facility available to your students 24/7 so they can never not locate their syllabus!—it’s also the case that expectations have gone up considerably around our use of them (and students’ reliance on them). Now I post my PPT slides on Brightspace after class, for example, something that requires multiple additional steps, assuming I remember to do it in the first place. (I never used to use PowerPoint, either, and I blame it and Brightspace, which both require incessant mousing, for my now chronic shoulder pain.) I used to give quizzes and midterms in class; now, they are all taken in Brightspace—but that too means many more steps than devising the questions and making copies, setting up all the many features just right and entering the questions in the optimal way. When we were all online, I posted weekly announcements for my classes: it turns out students really appreciated these, so I’ve kept doing them, but they take me (no kidding) hours to compose, both to make sure they are optimally clear and useful and because heaven forbid there’s a mistake in one, like a wrong deadline, that gets fixed in their minds or calendars in spite of any subsequent efforts to correct it! Recently, too, in a departmental discussion around class size and workload, one of my colleagues pointed out ruefully that “there didn’t used to be email” and that is such a good point, especially as our class sizes have gone up even as we became not just teachers but customer service representatives! (And yet somehow, without an LMS and without Outlook and without PowerPoint, we managed to do our jobs. Imagine that. Did we do a worse job? Maybe in some respects—accessibility seems like a key point here—but I really do wonder how much all of this apparatus actually helps, rather than hinders, us in our core mission.) How are things going otherwise in my classes? So far 19th-Century Fiction seems great (I hope it’s not just me who thinks so!). It’s the Austen to Dickens version this term, and I took the risk of assigning Pride and Prejudice, which as regular readers will know

How are things going otherwise in my classes? So far 19th-Century Fiction seems great (I hope it’s not just me who thinks so!). It’s the Austen to Dickens version this term, and I took the risk of assigning Pride and Prejudice, which as regular readers will know  My other class this term is a section of intro, once again the prosaically-named “Literature: How It Works.” But this time it’s in person, because I was so disheartened by the end of

My other class this term is a section of intro, once again the prosaically-named “Literature: How It Works.” But this time it’s in person, because I was so disheartened by the end of

It was a strange teaching term, at times hard, awkward, and demoralizing, but also at times invigorating, engaging, even restorative. This is true of every term, I suppose, but I really felt this emotional ebb and flow this time, probably because I am still grappling with what it means to carry on with my “normal” life after Owen’s death: I can’t really take any aspect of it for granted, and the more normal things seem in the moment the more

It was a strange teaching term, at times hard, awkward, and demoralizing, but also at times invigorating, engaging, even restorative. This is true of every term, I suppose, but I really felt this emotional ebb and flow this time, probably because I am still grappling with what it means to carry on with my “normal” life after Owen’s death: I can’t really take any aspect of it for granted, and the more normal things seem in the moment the more  I have always worried that students who attend irregularly are missing out on that broader learning experience, and also that sporadic attendance can become a self-fulfilling prophecy because if you just show up occasionally, you might not recognize the value of what we are doing or know how to join in to get the most out of it. The most obvious policy response is to require attendance, and I do believe in a version of “if you build it, they will come”—if you mandate it, they will (maybe, eventually, hopefully!) start to see the value of it. Mandatory attendance creates its own problems, though, from the administrative burden of recording it (especially with large classes) to the difficulty of having and applying fair policies that take accessibility and other issues into account and don’t lead to constant wrangling over what counts as a “legitimate” absence. For many years now I have not required or graded attendance, though I do always take attendance, so that I have some sense of who is or isn’t showing up and can reach out to anyone who seems like they might be in trouble. Before COVID, I also experimented with a range of different in-class exercises for credit, using them both for low-stakes practice at key course objectives and to “incentivize” being present. I think this is the approach I will go back to next year.

I have always worried that students who attend irregularly are missing out on that broader learning experience, and also that sporadic attendance can become a self-fulfilling prophecy because if you just show up occasionally, you might not recognize the value of what we are doing or know how to join in to get the most out of it. The most obvious policy response is to require attendance, and I do believe in a version of “if you build it, they will come”—if you mandate it, they will (maybe, eventually, hopefully!) start to see the value of it. Mandatory attendance creates its own problems, though, from the administrative burden of recording it (especially with large classes) to the difficulty of having and applying fair policies that take accessibility and other issues into account and don’t lead to constant wrangling over what counts as a “legitimate” absence. For many years now I have not required or graded attendance, though I do always take attendance, so that I have some sense of who is or isn’t showing up and can reach out to anyone who seems like they might be in trouble. Before COVID, I also experimented with a range of different in-class exercises for credit, using them both for low-stakes practice at key course objectives and to “incentivize” being present. I think this is the approach I will go back to next year. Another reason to return to more in-class work is the relentless encroachment of AI. Other people have written well about what it means for those of us whose life’s work is helping students learn to read, think, and write better, and about what we can and can’t, should and shouldn’t, do in response. (See

Another reason to return to more in-class work is the relentless encroachment of AI. Other people have written well about what it means for those of us whose life’s work is helping students learn to read, think, and write better, and about what we can and can’t, should and shouldn’t, do in response. (See

Actually, I kind of love the idea that the novel’s narrator “would rather have tea than everything else in the world” (me too!)—but of course this is absolutely not a passage from the novel; it’s just a jumble of nonsense. Students are already willing to put in a remarkable (to me) amount of effort “hiding” or “fixing” material they have copied from other sources, to conceal their reliance on it, but I doubt most of them are up to the task of getting crap like this into passable form. Mind you, to know it’s crap, they would need at least some familiarity with the novel: what shocked me with the ChatGPT cases I had this term was that they included quotations that were simply not in the actual assigned text, and the students didn’t even notice. As students get more familiar with the bot’s limitations, they may (may!) find it is actually less work (and less risk) to just do the reading and assignment themselves.

Actually, I kind of love the idea that the novel’s narrator “would rather have tea than everything else in the world” (me too!)—but of course this is absolutely not a passage from the novel; it’s just a jumble of nonsense. Students are already willing to put in a remarkable (to me) amount of effort “hiding” or “fixing” material they have copied from other sources, to conceal their reliance on it, but I doubt most of them are up to the task of getting crap like this into passable form. Mind you, to know it’s crap, they would need at least some familiarity with the novel: what shocked me with the ChatGPT cases I had this term was that they included quotations that were simply not in the actual assigned text, and the students didn’t even notice. As students get more familiar with the bot’s limitations, they may (may!) find it is actually less work (and less risk) to just do the reading and assignment themselves.

Next term: what a thought. A year ago the very idea of being back in the classroom was completely overwhelming. It seemed impossible, unthinkable. “How do they do that?” I puzzled as I reflected on

Next term: what a thought. A year ago the very idea of being back in the classroom was completely overwhelming. It seemed impossible, unthinkable. “How do they do that?” I puzzled as I reflected on  I’ve been ordering next year’s books — not because I’m that ahead of the game in general but because early ordering enables the bookstore to retain leftover copies from this year’s stock and students to get cash back at the end of term if they have books we’re using again. I’m teaching a couple of the same classes again in 2023-24 (my first-year writing class and Mystery & Detective Fiction) and so it isn’t too hard to get those orders sorted out. While I was at it, I thought I’d also make my mind up about which novels I’d assign for the Austen to Dickens course (this year I’m doing Dickens to Hardy — once upon a time I taught them both every year, but now I do them in alternate years) . . . and this has had me thinking about how my reading lists have changed over the past twenty years.

I’ve been ordering next year’s books — not because I’m that ahead of the game in general but because early ordering enables the bookstore to retain leftover copies from this year’s stock and students to get cash back at the end of term if they have books we’re using again. I’m teaching a couple of the same classes again in 2023-24 (my first-year writing class and Mystery & Detective Fiction) and so it isn’t too hard to get those orders sorted out. While I was at it, I thought I’d also make my mind up about which novels I’d assign for the Austen to Dickens course (this year I’m doing Dickens to Hardy — once upon a time I taught them both every year, but now I do them in alternate years) . . . and this has had me thinking about how my reading lists have changed over the past twenty years.

I could still add a fifth book to next year’s list if I want to. So far, I’m committed to Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and The Warden. In 2017 I assigned Persuasion, Vanity Fair, Jane Eyre, North and South, and Great Expectations for the same course; in 2013 the list was Persuasion, Waverley, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and North and South (I remember that year distinctly, because it was the year of the

I could still add a fifth book to next year’s list if I want to. So far, I’m committed to Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and The Warden. In 2017 I assigned Persuasion, Vanity Fair, Jane Eyre, North and South, and Great Expectations for the same course; in 2013 the list was Persuasion, Waverley, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, and North and South (I remember that year distinctly, because it was the year of the  This is my first term teaching both online and in person – not in the same course, but with one of each. So far I like it, actually. My in-person course is an old favorite, Mystery & Detective Fiction. I haven’t taught it in the classroom since Fall 2018, which feels a lot more than four years ago. I taught it online more recently, with some success, measured at least by the number of students who showed up in my Fall 2022 classes at least in part because (according to them) they’d enjoyed it a lot. I’ve remarked here before about the oddity that this has become my most frequently taught course, because it’s such a popular elective. It’s full again this term, at 64. I am grateful for its familiarity: I hope to be able to relax into it. Usually it sparks some of the liveliest discussion of any of my classes, I think because everyone’s there out of interest (it doesn’t fulfill any requirements, so nobody has been coerced into taking it). We warmed up this week with “big picture” stuff about genre fiction, with an overview of the history of detective fiction, and then, today, with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Monday we start The Moonstone, which I omitted, reluctantly, from the online version. I was rereading our first instalment this afternoon and it’s just such a lot of fun. I hope they think so too!

This is my first term teaching both online and in person – not in the same course, but with one of each. So far I like it, actually. My in-person course is an old favorite, Mystery & Detective Fiction. I haven’t taught it in the classroom since Fall 2018, which feels a lot more than four years ago. I taught it online more recently, with some success, measured at least by the number of students who showed up in my Fall 2022 classes at least in part because (according to them) they’d enjoyed it a lot. I’ve remarked here before about the oddity that this has become my most frequently taught course, because it’s such a popular elective. It’s full again this term, at 64. I am grateful for its familiarity: I hope to be able to relax into it. Usually it sparks some of the liveliest discussion of any of my classes, I think because everyone’s there out of interest (it doesn’t fulfill any requirements, so nobody has been coerced into taking it). We warmed up this week with “big picture” stuff about genre fiction, with an overview of the history of detective fiction, and then, today, with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Monday we start The Moonstone, which I omitted, reluctantly, from the online version. I was rereading our first instalment this afternoon and it’s just such a lot of fun. I hope they think so too!

October was a terrible reading month for me. I didn’t even start many books, much less finish them. A last minute push (and, I’ll admit, a bit of fed-up skimming) got me to the end of Kate Atkinson’s Shrines of Gaiety, which I had acquired precisely because I figured that, whatever gripes I have had in the past with her

October was a terrible reading month for me. I didn’t even start many books, much less finish them. A last minute push (and, I’ll admit, a bit of fed-up skimming) got me to the end of Kate Atkinson’s Shrines of Gaiety, which I had acquired precisely because I figured that, whatever gripes I have had in the past with her

In 19th-Century Fiction we have been working on Middlemarch for a couple of weeks. I wish I could say it is going well. I don’t think it’s going badly exactly, but honestly this term I don’t really know. Attendance is just appalling: most days, maybe 60% of the class shows up, which is unprecedented, in my fairly long experience. I don’t know what to make of this. I know it’s not personal, or at least I’m trying not to take it personally, but that doesn’t make it any less disheartening. The students who are present are pretty quiet; I think – I hope – they are engaged, but much of the time it’s hard to tell, and I worry that at this point I am mostly performing enthusiasm, not eliciting it. The ones who do speak up have good things to say, but I’m not used to having to work so hard to get anything out of the class, to get any energy back from them. I’m going to keep trying! The ones who are showing up deserve no less, and I remain hopeful that between us we can and will make the most of this opportunity to read this great novel together.

In 19th-Century Fiction we have been working on Middlemarch for a couple of weeks. I wish I could say it is going well. I don’t think it’s going badly exactly, but honestly this term I don’t really know. Attendance is just appalling: most days, maybe 60% of the class shows up, which is unprecedented, in my fairly long experience. I don’t know what to make of this. I know it’s not personal, or at least I’m trying not to take it personally, but that doesn’t make it any less disheartening. The students who are present are pretty quiet; I think – I hope – they are engaged, but much of the time it’s hard to tell, and I worry that at this point I am mostly performing enthusiasm, not eliciting it. The ones who do speak up have good things to say, but I’m not used to having to work so hard to get anything out of the class, to get any energy back from them. I’m going to keep trying! The ones who are showing up deserve no less, and I remain hopeful that between us we can and will make the most of this opportunity to read this great novel together.