I have read some books since Fayne, honest I have! I just haven’t had the bandwidth, as the saying goes, to write them up properly—which is a shame, as some of them have been very good. So here’s a catch-up post, to be sure I don’t let them slip by entirely unremarked.

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place.

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place.

I just loved this novel, which struck me as elegantly balanced between Standish’s individual experience, written with a pitch-perfect blend of comedy and pathos, and parable-like reflections on life and death more generally. Three small samples, just as teasers, from different moments in the book—one from before Standish’s slip and fall, one from his time in the water, and the other from the perspective of one of his shipboard companions:

The whole world was so quiet that Standish felt mystified. The lone ship plowing through the broad sea, the myriad of stars fading out of the wide heavens—these were all elemental things that soothed and troubled Standish. It was as if he were learning for the first time that all the vexatious problems of his life were meaningless and unimportant; and yet he felt ashamed at having had them in the same world that could create such a scene as this.

Not dead yet, Standish thought. And not alive either; before walking away and leaving his inert remains to shift for themselves it would be best to think of life as he had lived it; not of the ordinary events . . . but of the extraordinary things that had happened in his insufficient thirty-five years. And with each thought a pang came to his heart that had shattered, a pang of regret that he could not go on like other men having new extraordinary experiences day after day.

He went down to his favorite spot on the well deck and gazed out at the sea and the materializing stars in the heaven. It defied his imagination. You could not think of this vastness one moment and then the next moment think of a puny bundle of humanity lost in its midst. One was so much bigger than the other; the human mind simply could not cope with the two together.

I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite:

I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite:

The Flaw

The best thing about a hand-made pattern

is the flaw.

Sooner or later in a hand-loomed rug,

among the squares and flattened triangles,

a little red nub might soar above a blue field,

or a purple cross might sneak in between

the neat ochre teeth of the border.

The flaw we live by, the wrong color floss,

now wreathes among the uniform strands

and, because it does not match,

makes a red bird fly,

turning blue field into sky.

It is almost, after long silence, a word

spoken aloud, a hand saying through the flaw,

I’m alive, discovered by your eye.

Peacock talks often in the book about her interest in poetic form; I liked this explanation of its value:

Form does something else vigorously physical: it compresses. Because you have to meet a limit—a line length, a number of syllables, a rhyme—you have to stretch or curl a thought to meet that requirement. Curiously, as the lyrical mind works to answer that demand, the unconscious is freed to experience its most playful and most dangerous feelings. Form is safety, the safe place in which we can be most volatile.

A Friend Sails in on a Poem is not an effusive book, but there’s something uplifting about its record of a friendship between women that is shaped by shared artistic and intellectual interests and not threatened by the differences between them as people and as writers. There’s no melodrama, not even really any narrative tension, around their friendship; the book’s momentum comes solely and, I thought, admirably simply from the movement of the two poets in tandem through time.

I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer.

I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer.

Smith’s story also felt very specific, very particular to me. She remarks in a few instances that she is writing it because perhaps it will become something other people can use, but her care not to extrapolate or generalize, while I suppose appropriate to such a personal kind of memoir, seemed to me to work against that possibility. Others might well disagree, and I can see making the argument that the portable value of her book lies precisely in its modeling of how to be honest and vulnerable about something so intimate. In the spirit of her viral poem “Good Bones,” You Could Make This Place Beautiful (a title which itself comes from that poem), Smith’s book is, ultimately, about repair, about how even a situation that seems like a hopeless ruin can, with some time and a lot of effort, become habitable again:

Something about being at the ocean always reminds me of how small I am, but not in a way that makes me feel insignificant. It’s a smallness that makes me feel a part of the world, not separate from it. I sat down in a lounge chair and opened the magazine to my poem [“Bride”], the thin pages flapping in the wind. IN that moment, I felt like I was where I was meant to be, doing what I was supposed to be doing.

Life, like a poem, is a series of choices.

Something had shifted, maybe just slightly, but perceptibly. I remember feeling the smile on my face the whole walk back to the hotel, hoping it didn’t seem odd to the people around me. I stopped at the drawbridge that lifted so the boats could go under. The whole street lifted up right in front of me. Nothing seemed impossible anymore. Everything was possible.

OK, maybe! The optimism is welcome, and maybe authentic, though (and again, others might disagree) it feels a bit forced to me here, whereas “Good Bones” has a quality of wistfulness to it that I like better.

Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his Slough House books that I’ve read. It was thoroughly entertaining, and I read it at a brisk pace as a result, but by the end it did strike me as a risk that the series’ signature elements, including Lamb’s flatulence and the various other Slow Horses’ quirks, could wear a bit thin.

Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his Slough House books that I’ve read. It was thoroughly entertaining, and I read it at a brisk pace as a result, but by the end it did strike me as a risk that the series’ signature elements, including Lamb’s flatulence and the various other Slow Horses’ quirks, could wear a bit thin.

I’m reading for work too, of course, most recently The Murder of Roger Ackroyd in Mystery & Detective Fiction and a cluster of works on ‘fallen women’ for my Victorian ‘Woman Question’ seminar—DGR’s “Jenny,” Augusta Webster’s “A Castaway,” and Elizabeth Gaskell’s “Lizzie Leigh,” a story I love (I wrote about it here the last time I taught it in person, which seems a lifetime ago). As always, I am thinking about ways to shake up the reading list for the mystery class, if only to bring in at least one book more recent than the early 1990s, which used to seem very current but of course is not any longer. A student asked today, in the context of our discussion of the moral discomfort possibly created by the “cozy” subgenre, whether we were going to talk about true crime in the course. We aren’t, because no example of it is assigned and because the course is specifically about crime “fiction”, but one idea I’ve been kicking around is Denise Mina’s The Long Drop, which is a novelization of a true crime case. I haven’t read it yet, so that’s obviously what I need to do next, but I listened to a podcast episode with her talking about it and it was really fascinating.

I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir’s Hotel Silence, since I liked Butterflies in November a lot. I hope to get through all the books in that stack before they come due—but I know I’m not the only reader who finds that their aspirations of this kind, and the pace of their library holds, can exceed their capacity!

I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir’s Hotel Silence, since I liked Butterflies in November a lot. I hope to get through all the books in that stack before they come due—but I know I’m not the only reader who finds that their aspirations of this kind, and the pace of their library holds, can exceed their capacity!

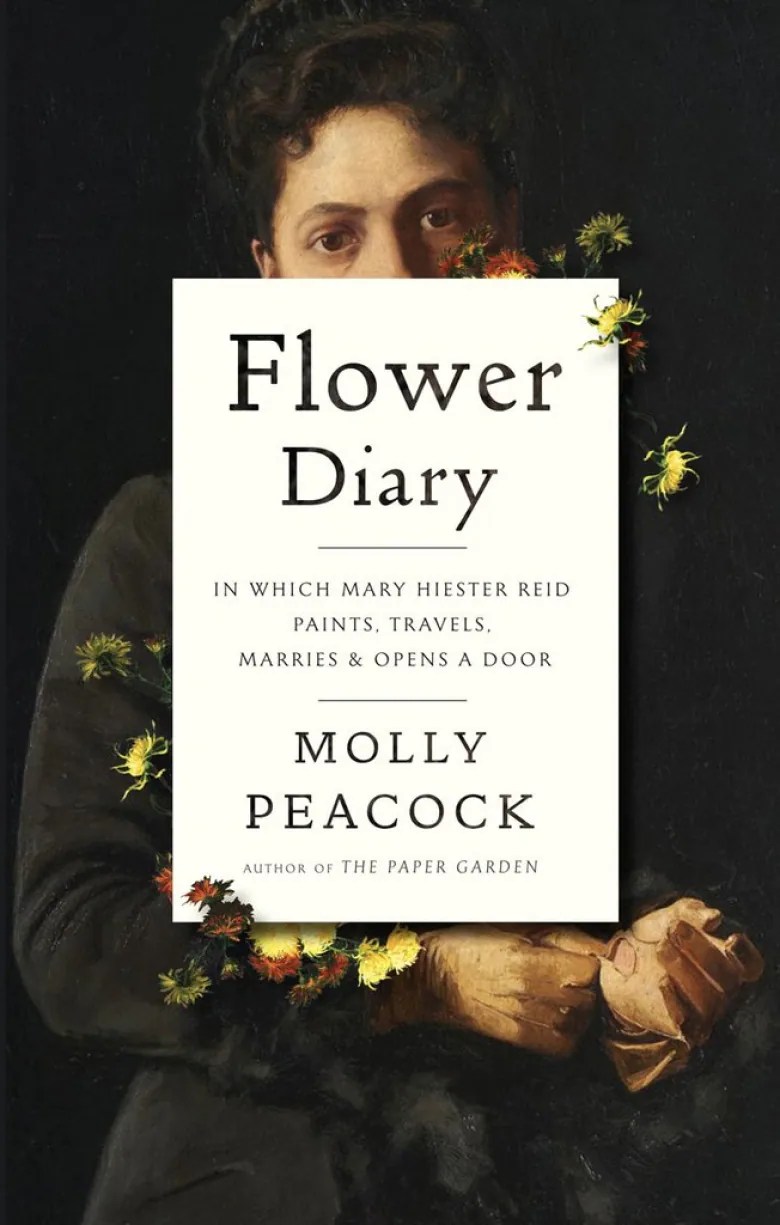

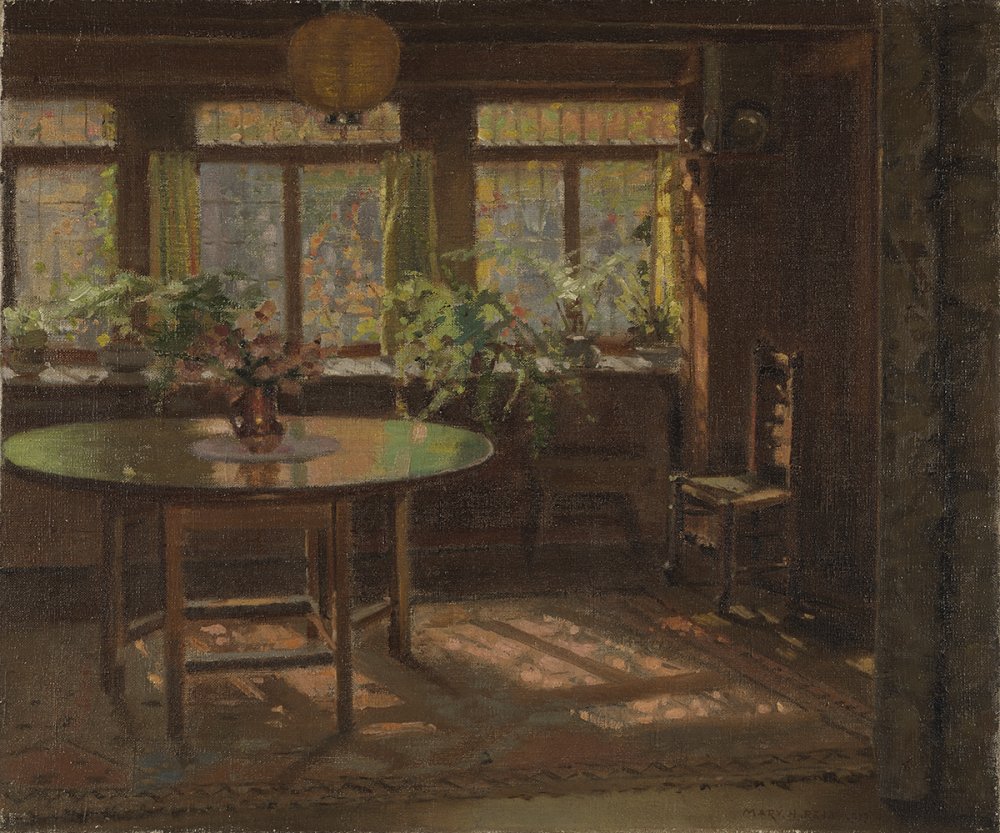

In an era where Mary Cassatt eschewed marriage and a fully adult life to live with her parents in Paris so that she could produce her work, Mary Hiester bounded into an adulthood of painting with a grown-up’s problems of money and sex and logistics . . . Existing with an ambitious man in a socially constricted world for women of which a person today can barely grasp the demeaning dimensions, she lived, by her lights, “cheerfully.” She painted around the obstacles of an artist’s life by employing a woman’s emblem, the rose, and later an emblem of independence, the tree.

In an era where Mary Cassatt eschewed marriage and a fully adult life to live with her parents in Paris so that she could produce her work, Mary Hiester bounded into an adulthood of painting with a grown-up’s problems of money and sex and logistics . . . Existing with an ambitious man in a socially constricted world for women of which a person today can barely grasp the demeaning dimensions, she lived, by her lights, “cheerfully.” She painted around the obstacles of an artist’s life by employing a woman’s emblem, the rose, and later an emblem of independence, the tree. Like Peacock’s earlier, similar work

Like Peacock’s earlier, similar work

Flower Diary follows Mary’s artistic development, integrating it with the story of her personal life—as indeed the two were intricately related in reality. There are lots of parts to both, including the art school Mary and George ran and many trips to Paris and Spain and time spent in an artistic community in Onteora, in the Catskills. Peacock emphasizes Mary’s “persistence” as an artist. Hers was not a bad marriage, or an unsuccessful career: George was a supportive partner, and she was productive and accomplished and recognized. The times were not kind to ambitious women in general, though, or to women artists more particularly. “I don’t know where the assurance and conviction required for Mary’s sort of persistence comes from precisely,” Peacock comments,

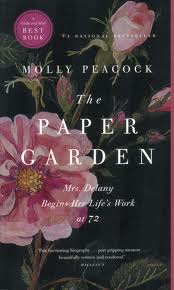

Flower Diary follows Mary’s artistic development, integrating it with the story of her personal life—as indeed the two were intricately related in reality. There are lots of parts to both, including the art school Mary and George ran and many trips to Paris and Spain and time spent in an artistic community in Onteora, in the Catskills. Peacock emphasizes Mary’s “persistence” as an artist. Hers was not a bad marriage, or an unsuccessful career: George was a supportive partner, and she was productive and accomplished and recognized. The times were not kind to ambitious women in general, though, or to women artists more particularly. “I don’t know where the assurance and conviction required for Mary’s sort of persistence comes from precisely,” Peacock comments, “Going cheerfully on with the task”: there’s no doubt that this is admirable, and getting on with things rather than enacting one’s rage may indeed by a truly adult—the only possible—adult response to the complexities of life, including married life. There’s ultimately something a bit stolid about the woman we meet in Flower Diary, though, or about Peacock’s characterization of her anyway, and I think that’s why Flower Diary, interesting as it is, and full as it is of beautiful pictures and wonderful bits of writing, was a disappointment to me after the revelation that was The Paper Garden. The story of Mary Delany discovering and fulfilling her own peculiar creative genius late in life was so exhilarating; it seemed to offer so much hope. It is, as I said in my post about it “a subversive, celebratory view of growing older as a woman”: in Peacock’s wonderful phrasing, “Her whole life flowed to the place where she plucked that moment.”

“Going cheerfully on with the task”: there’s no doubt that this is admirable, and getting on with things rather than enacting one’s rage may indeed by a truly adult—the only possible—adult response to the complexities of life, including married life. There’s ultimately something a bit stolid about the woman we meet in Flower Diary, though, or about Peacock’s characterization of her anyway, and I think that’s why Flower Diary, interesting as it is, and full as it is of beautiful pictures and wonderful bits of writing, was a disappointment to me after the revelation that was The Paper Garden. The story of Mary Delany discovering and fulfilling her own peculiar creative genius late in life was so exhilarating; it seemed to offer so much hope. It is, as I said in my post about it “a subversive, celebratory view of growing older as a woman”: in Peacock’s wonderful phrasing, “Her whole life flowed to the place where she plucked that moment.”

The good news isn’t specifically about what’s happening in my classes this week (although I hope there is some connection): it’s good news about my teaching more generally. This week I learned that I am this year’s recipient of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Award for Excellence in Teaching.

The good news isn’t specifically about what’s happening in my classes this week (although I hope there is some connection): it’s good news about my teaching more generally. This week I learned that I am this year’s recipient of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Award for Excellence in Teaching. Given the role that Novel Readings has played in my teaching life–as a vehicle for reflection and a place where I have both shared and received ideas and encouragement about teaching–it is gratifying to know that my blogging was part of the case made on my behalf, and that my success at generating “conversations both within the university and in wider circles” was cited by the committee that selected me to receive the award this year. I started blogging about pedagogy when this kind of outward-facing work was still relatively uncommon for academics and was (as it still largely remains) not entirely congruent with the university’s standard operating procedures. I have found it intrinsically valuable, for the process itself and for the conversations and communities it has brought me into. For that reason alone I would keep it up in any case, but I admit it is nice to have some institutional recognition that it contributes to our core mission.

Given the role that Novel Readings has played in my teaching life–as a vehicle for reflection and a place where I have both shared and received ideas and encouragement about teaching–it is gratifying to know that my blogging was part of the case made on my behalf, and that my success at generating “conversations both within the university and in wider circles” was cited by the committee that selected me to receive the award this year. I started blogging about pedagogy when this kind of outward-facing work was still relatively uncommon for academics and was (as it still largely remains) not entirely congruent with the university’s standard operating procedures. I have found it intrinsically valuable, for the process itself and for the conversations and communities it has brought me into. For that reason alone I would keep it up in any case, but I admit it is nice to have some institutional recognition that it contributes to our core mission. And it has felt even better sharing my good news and basking in people’s happiness on my behalf. I got a lot of help from my friends, both online and off, when things went badly for me; now everyone has been wonderfully supportive about this good news. Social media certainly has its down sides (as we are only too well aware at this point), but there’s also something magical about the way it creates a vast web of connections–intangible perhaps, but still very real–between so many people across such distances. I hesitated before putting my good news out there in case it seemed self-aggrandizing, but I’m so glad I did. Why should we be afraid to invite a bit of cheering for our accomplishments, after all? I was reminded of one of my favorite points from Molly Peacock’s wonderful and inspiring book

And it has felt even better sharing my good news and basking in people’s happiness on my behalf. I got a lot of help from my friends, both online and off, when things went badly for me; now everyone has been wonderfully supportive about this good news. Social media certainly has its down sides (as we are only too well aware at this point), but there’s also something magical about the way it creates a vast web of connections–intangible perhaps, but still very real–between so many people across such distances. I hesitated before putting my good news out there in case it seemed self-aggrandizing, but I’m so glad I did. Why should we be afraid to invite a bit of cheering for our accomplishments, after all? I was reminded of one of my favorite points from Molly Peacock’s wonderful and inspiring book  The prints of them in

The prints of them in  “It’s just a flower!” I mentally protested as I read that the first time. And yet the more times I look at the picture—now, inevitably, with that description in my mind—the more I see at least the possibility of its eroticism. As Peacock points out, “Anyone who has ever read a seventeenth-century metaphysical poet knows that the sacred and the sexual are never very far apart. Nor are the botanical and the anatomical.” Mrs. Delany’s flowers look, superficially, very pretty: simple, safe, and feminine. When Peacock herself first saw them, she was disappointed in her own reaction: “I felt nearly ashamed about how deeply I swooned over her work, because the botanicals seemed almost fuddy-duddy.” They belong to “the tiny, boundaried world that has its sources in handiwork,” the kinds of crafts her grandmother did. That’s not the artistic heritage she seeks for herself (“Georges Braque or Pablo Picasso probably would have hated them”) but she is “hooked,” “sunk.” At first, though, she didn’t see the collages quite as she would later come to, and as she would like us to: “They all come out of the darkness, intense and vaginal, bright on their black backgrounds as if, had she possessed one, she had shined a flashlight on nine hundred and eight-five flowers’ cunts.” Is seeing (showing) the flowers this way a means of exorcising the fuddy-duddy from them, or from herself?

“It’s just a flower!” I mentally protested as I read that the first time. And yet the more times I look at the picture—now, inevitably, with that description in my mind—the more I see at least the possibility of its eroticism. As Peacock points out, “Anyone who has ever read a seventeenth-century metaphysical poet knows that the sacred and the sexual are never very far apart. Nor are the botanical and the anatomical.” Mrs. Delany’s flowers look, superficially, very pretty: simple, safe, and feminine. When Peacock herself first saw them, she was disappointed in her own reaction: “I felt nearly ashamed about how deeply I swooned over her work, because the botanicals seemed almost fuddy-duddy.” They belong to “the tiny, boundaried world that has its sources in handiwork,” the kinds of crafts her grandmother did. That’s not the artistic heritage she seeks for herself (“Georges Braque or Pablo Picasso probably would have hated them”) but she is “hooked,” “sunk.” At first, though, she didn’t see the collages quite as she would later come to, and as she would like us to: “They all come out of the darkness, intense and vaginal, bright on their black backgrounds as if, had she possessed one, she had shined a flashlight on nine hundred and eight-five flowers’ cunts.” Is seeing (showing) the flowers this way a means of exorcising the fuddy-duddy from them, or from herself?