Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil.

Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil.

Anyone who’s read Pride and Prejudice will immediately recognize this moment. Jane has come down with a cold thanks to her mother’s insistence that she ride to Netherfield “because it seems likely to rain; and then you must stay all night”—a highly successful strategy, as it turns out. Elizabeth, “feeling really anxious, was determined to go to her, though the carriage was not to be had; and as she was no horsewoman, walking was her only alternative.” And so she sets out on foot,

crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and springing over puddles with impatient activity, and finding herself at last within view of the house, with weary ankles, dirty stockings, and a face glowing with the warmth of exercise.

The residents of Netherfield are shocked at her impropriety, but though they notice that her petticoat is “six inches deep in mud,” not one of them gives a moment’s thought to the extra work Elizabeth’s “country-town indifference to decorum” creates for the household staff. Neither, as far as we know, do Jane and Elizabeth: in this privileged indifference to the labor that supports their lifestyle, if in nothing else, they are very much at one with their hosts.

Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. (Exhibit A, the worst.) I have also been tired of the endless appetite for all things Austen for a long time: so many of the results seem either too fannish or just plain parasitic. Finally, I am not by personal taste a Janeite (I like only two of her novels, though I am capable, in my better moods, of appreciating what’s excellent about a couple of the others). It just seemed so unlikely that I’d enjoy Longbourn!

Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. (Exhibit A, the worst.) I have also been tired of the endless appetite for all things Austen for a long time: so many of the results seem either too fannish or just plain parasitic. Finally, I am not by personal taste a Janeite (I like only two of her novels, though I am capable, in my better moods, of appreciating what’s excellent about a couple of the others). It just seemed so unlikely that I’d enjoy Longbourn!

And yet enjoy it I did, quite a lot, which naturally has got me thinking about why—about what Baker does that worked for me where other books in the same vein have failed. I overcame my prejudices enough to try it in the first place because I really liked A Country Road, A Tree: the writer of that smart, sensitive novel about one great writer probably (I reasoned) would not be cheap or shallow in her novel inspired by another. But A Country Road, A Tree is a biographical novel, a different subcategory of literary homage: it undertakes to investigate the writing process, not to rewrite the results—an approach which risks pitting the new author against the old, or, worse, setting the new author above the old. I think Longbourn succeeds because it sits beside the original: Baker is rounding out the story Austen tells, adding to it in ways that inevitably complicate how we think about it, but she is also clearly writing her own novel, and it stands up well on those terms. In fact, at times I wondered if (marketing advantage aside) Baker really needed the Austen hook: couldn’t Longbourn just have been a historical novel about servants in any elegant Regency household?

I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its excessively well-known inspiration. It was fun to know exactly what was going on upstairs even when Baker’s characters don’t—when Darcy first proposes to Elizabeth at Hunsford, for example. Sarah, who has accompanied Lizzie on the trip to see Charlotte, now Mrs. Collins, is busy with her own thoughts, especially about her relationship with James Smith, when she hears “a door shut within the house”:

I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its excessively well-known inspiration. It was fun to know exactly what was going on upstairs even when Baker’s characters don’t—when Darcy first proposes to Elizabeth at Hunsford, for example. Sarah, who has accompanied Lizzie on the trip to see Charlotte, now Mrs. Collins, is busy with her own thoughts, especially about her relationship with James Smith, when she hears “a door shut within the house”:

There were quick footfalls coming down the hall. She got up off the step and stood aside just in time, or he would have walked straight through her; the front door was whisked wide, and Mr. Darcy strode past her shadow, and marched down the path. He left the gate swinging … Back in the house, she crept down the hall and cocked an ear outside the parlour door. She could hear the quiet sounds of Elizabeth crying.

I guess we do need to know Pride and Prejudice to appreciate this moment fully, but that doesn’t mean Longbourn needed to be attached to the other novel in this way to fulfill its own (other) aims.

The connection is more significant in the other direction, I think: having read Longbourn, you are likely to be more aware of the elements that are absent from Pride and Prejudice the next time you read Austen’s novel. I say “absent” rather than “missing from” because I think the former allows us to acknowledge the limited scope of Pride and Prejudice without insisting on that as a fault in it: it is what it is, and Longbourn is something else, is about something else—not the same themes of manners and morals, not the same political themes or philosophies, as Pride and Prejudice, but other social and political themes, including class (which of course Austen’s novel is also about), race, and empire, topics which are relevant to the lives of Austen’s characters (and especially to their wealth) in ways the original novel does not explicitly acknowledge. Of course the result is some (mostly implicit) critique, especially around the source of the Bingleys’ wealth, which Austen tells us was “acquired by trade” but which Baker attributes more specifically to sugar. “I would love to be in sugar,” exclaims the little maid Polly.

“You’d go sailing out”—James traced a triangle in the air with a fork—”loaded to the gunwales with English guns and ironware. You’d follow the trade-winds south to Africa … In African, you can trade all that, and guns, for people; you load them up in your hold, and you ship them off to the West indies, and trade them there for sugar, and then you ship the sugar back home to England. The triangular Trade, they call it.

“I didn’t know they paid for sugar that way,” says Polly uncomfortably, “with people.” Another pointed moment comes near the end, when Sarah tells Elizabeth (whom she is now serving at Pemberley) that she is leaving. “But where will you go, Sarah?” Elizabeth asks; “What can a woman do, all on her own, and unsupported?” “Work,” Sarah replies. “I can always work.” That, of course, is an alternative Elizabeth herself never contemplates when faced with the dire prospect of marrying Mr. Collins or risking poverty.

But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her.

But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her.

We have had more storms since the last time I posted but happily no more storm days, so we are still on schedule … for now! (In fact, things are looking

We have had more storms since the last time I posted but happily no more storm days, so we are still on schedule … for now! (In fact, things are looking  I really did enjoy rereading the novel this time, especially the reliably hilarious as well as deliciously subversive final encounter between Elizabeth and Lady Catherine. One thing we spent a fair amount of time on in class is the way Austen manipulates us into liking or disliking characters, only, much of the time, to undercut or at least complicate our “first impressions” so that we realize we are vulnerable to the same interpretive mistakes as the characters. In this respect I think even Mr Collins gets a bit of a reprieve from our initial distaste. Not only is his offer to Lizzie actually quite honorable, despite also being laughable, considering he has no obligation to make up to the Bennet sisters for the future loss of their home, but at Hunsford we see that while he is still absurd, he treats Charlotte well and has made it possible for her to live a dignified life. I don’t think there’s any backtracking on Lady Catherine, though: she remains an antagonist to that bitterly delightful end:

I really did enjoy rereading the novel this time, especially the reliably hilarious as well as deliciously subversive final encounter between Elizabeth and Lady Catherine. One thing we spent a fair amount of time on in class is the way Austen manipulates us into liking or disliking characters, only, much of the time, to undercut or at least complicate our “first impressions” so that we realize we are vulnerable to the same interpretive mistakes as the characters. In this respect I think even Mr Collins gets a bit of a reprieve from our initial distaste. Not only is his offer to Lizzie actually quite honorable, despite also being laughable, considering he has no obligation to make up to the Bennet sisters for the future loss of their home, but at Hunsford we see that while he is still absurd, he treats Charlotte well and has made it possible for her to live a dignified life. I don’t think there’s any backtracking on Lady Catherine, though: she remains an antagonist to that bitterly delightful end: In British Literature After 1800 we are still reading poetry and I am still struggling with “how to balance attention to context and content with attention to form,” as I put it in

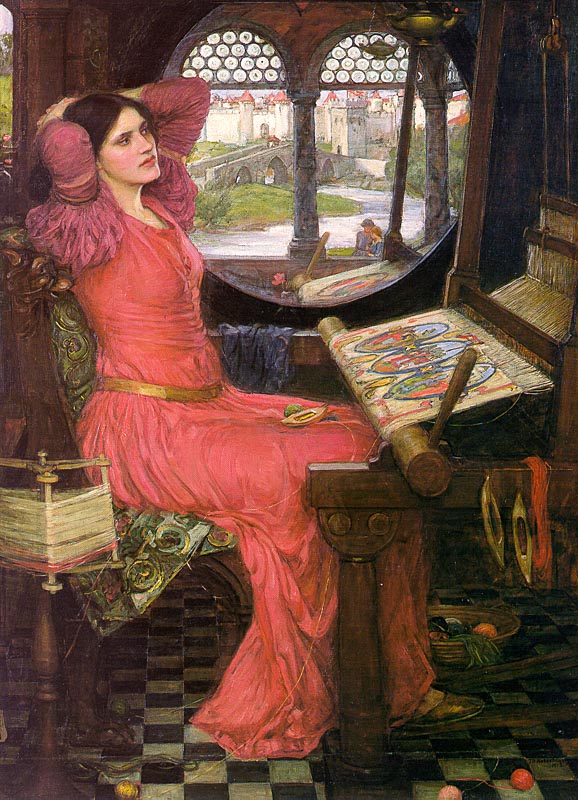

In British Literature After 1800 we are still reading poetry and I am still struggling with “how to balance attention to context and content with attention to form,” as I put it in  This is hardly a radical strategy, including for me. I do often (and did this term) provide study questions for the novels in my 19th-Century Fiction classes, for example, to help students organize their observations as they read the long books–to know what, of all the many details flooding past them, to really pay attention to. But I also find it pretty easy to ask questions in 19th-Century Fiction that will get at least some answers, and usually lots of them, because we always have plot and character as starting points, from which we can level up to questions about form and theme. Maybe because I don’t teach poetry often, I underestimated the difference it makes to be working on, not just poetry, but poetry much of which is in a somewhat archaic diction. My impression (though I may be mistaken) is that many of the students are struggling with the literal meaning of the poems–their basic paraphraseable content. Perhaps, too, the variety in our reading list that keeps things interesting for me (and is to some extent necessitated by the survey format) is making things harder for them because each poet is so different and thus makes different demands on our attention as readers. With that in mind, in the study questions I came up with I tried to make the assigned poems more legible for them, combining questions about theme with prompts to consider form, and making some connections across the poems.

This is hardly a radical strategy, including for me. I do often (and did this term) provide study questions for the novels in my 19th-Century Fiction classes, for example, to help students organize their observations as they read the long books–to know what, of all the many details flooding past them, to really pay attention to. But I also find it pretty easy to ask questions in 19th-Century Fiction that will get at least some answers, and usually lots of them, because we always have plot and character as starting points, from which we can level up to questions about form and theme. Maybe because I don’t teach poetry often, I underestimated the difference it makes to be working on, not just poetry, but poetry much of which is in a somewhat archaic diction. My impression (though I may be mistaken) is that many of the students are struggling with the literal meaning of the poems–their basic paraphraseable content. Perhaps, too, the variety in our reading list that keeps things interesting for me (and is to some extent necessitated by the survey format) is making things harder for them because each poet is so different and thus makes different demands on our attention as readers. With that in mind, in the study questions I came up with I tried to make the assigned poems more legible for them, combining questions about theme with prompts to consider form, and making some connections across the poems.

In British Literature After 1800 we are skipping briskly through our small sample of Romantic poets. The rapid pace is at once the blessing and the curse of a survey course with a mandate to span more than 200 years of writing in multiple genres: we don’t spend long enough in any one place to go into a great deal of depth, which means we also don’t spend long enough on any one topic to get tired of it. I enjoy the variety myself, including the chance to talk about genres and examples that don’t come up in the courses I teach more often–such as Romantic poetry! In fact, because the introductory courses I’ve taught for the last several years have been either Introduction to Prose and Fiction or Pulp Fiction, I’ve spend hardly any time on poetry at all except for Close Reading, and the last time I taught that was Fall 2017. So I’m having fun, but also feeling a bit wobbly about how to balance attention to context and content with attention to form.

In British Literature After 1800 we are skipping briskly through our small sample of Romantic poets. The rapid pace is at once the blessing and the curse of a survey course with a mandate to span more than 200 years of writing in multiple genres: we don’t spend long enough in any one place to go into a great deal of depth, which means we also don’t spend long enough on any one topic to get tired of it. I enjoy the variety myself, including the chance to talk about genres and examples that don’t come up in the courses I teach more often–such as Romantic poetry! In fact, because the introductory courses I’ve taught for the last several years have been either Introduction to Prose and Fiction or Pulp Fiction, I’ve spend hardly any time on poetry at all except for Close Reading, and the last time I taught that was Fall 2017. So I’m having fun, but also feeling a bit wobbly about how to balance attention to context and content with attention to form.

Given the cyclical nature of the academic life as well as the recurrence of texts and topics in the classes I teach most often, there are lots of things I might be saying “Not again!” about! This week, however, the particularly irksome repetition is the disruption to the start of term thanks to a big storm–not

Given the cyclical nature of the academic life as well as the recurrence of texts and topics in the classes I teach most often, there are lots of things I might be saying “Not again!” about! This week, however, the particularly irksome repetition is the disruption to the start of term thanks to a big storm–not  So what, besides calming my nerves (and perhaps theirs as well), is on the agenda for our remaining classes this week? Well, in British Literature After 1800 Friday will be our (deferred) Wordsworth day. In my opening lecture on Monday I emphasized the arbitrariness of literary periods and the challenges of telling coherent stories based on chronology, the way a survey course is set up to do. But I also stressed the value of knowing when things were written, both because putting them in order is useful for understanding the way literary conversations and influences unfold, with writers often responding or reacting to or resisting each other, and because historical contexts can be crucial to recognizing meaning. My illustrative text for this point was Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud,” which (as I told them) is the first poem I ever memorized, as a child. It was perfectly intelligible to me then, and it is still a charming and accessible poem to readers who know nothing at all about what we now call ‘Romanticism.’ Without historical context, it seems anything but radical–and yet Wordsworth in his day (at least, in his early days) was considered literally revolutionary. His poetry “is one of the innovations of the time,” William Hazlitt wrote in “The Spirit of the Age”;

So what, besides calming my nerves (and perhaps theirs as well), is on the agenda for our remaining classes this week? Well, in British Literature After 1800 Friday will be our (deferred) Wordsworth day. In my opening lecture on Monday I emphasized the arbitrariness of literary periods and the challenges of telling coherent stories based on chronology, the way a survey course is set up to do. But I also stressed the value of knowing when things were written, both because putting them in order is useful for understanding the way literary conversations and influences unfold, with writers often responding or reacting to or resisting each other, and because historical contexts can be crucial to recognizing meaning. My illustrative text for this point was Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud,” which (as I told them) is the first poem I ever memorized, as a child. It was perfectly intelligible to me then, and it is still a charming and accessible poem to readers who know nothing at all about what we now call ‘Romanticism.’ Without historical context, it seems anything but radical–and yet Wordsworth in his day (at least, in his early days) was considered literally revolutionary. His poetry “is one of the innovations of the time,” William Hazlitt wrote in “The Spirit of the Age”; There’s no doubt that if I were teaching Mansfield Park these questions would be a big part of our discussion, as they are when I teach The Moonstone. I haven’t so far arrived at any ideas about how — or, to some extent, why — we would take up this specific line of inquiry in our work on Pride and Prejudice. Perhaps I am too prone to let the novels I assign set their own terms for our analysis–to rely on their overt topical engagements more than what they leave out or obscure–but this particular novel doesn’t seem to be about race and empire, even though its characters live in a world where these things (while never, I think, explicitly mentioned) matter a lot. Beyond acknowledging that fact,

There’s no doubt that if I were teaching Mansfield Park these questions would be a big part of our discussion, as they are when I teach The Moonstone. I haven’t so far arrived at any ideas about how — or, to some extent, why — we would take up this specific line of inquiry in our work on Pride and Prejudice. Perhaps I am too prone to let the novels I assign set their own terms for our analysis–to rely on their overt topical engagements more than what they leave out or obscure–but this particular novel doesn’t seem to be about race and empire, even though its characters live in a world where these things (while never, I think, explicitly mentioned) matter a lot. Beyond acknowledging that fact,  “In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.” – Fitzwilliam Darcy, in Pride and Prejudice

“In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.” – Fitzwilliam Darcy, in Pride and Prejudice Not that there’s anything wrong with that! Lots of (maybe even most) critical work is at least implicitly advocating on behalf of its specific topic — whether for its underestimated importance to literary history or for its political efficacy or for a right understanding of its aesthetic properties. Romance is a special case, too: as pretty much everyone I’ve read who writes about romance says at some point, it seems to call for overt special pleading simply because it is so routinely dismissed and its readers and writers so routinely shamed. If Regis seems at times to protest too much, it’s probably just that she knew her choice of subject would be met with skepticism, if not derision, and not just by her academic colleagues. (I expect that more recent scholarship is less defensive, as genre fiction and popular culture more generally have become increasingly familiar parts of the academic landscape. Eric Selinger and Sarah Frantz’s collection New Approaches to Popular Romance Fiction, which came out in 2012, is also on my reading list; I’ll be curious to see if I’m right that the tone has changed.)

Not that there’s anything wrong with that! Lots of (maybe even most) critical work is at least implicitly advocating on behalf of its specific topic — whether for its underestimated importance to literary history or for its political efficacy or for a right understanding of its aesthetic properties. Romance is a special case, too: as pretty much everyone I’ve read who writes about romance says at some point, it seems to call for overt special pleading simply because it is so routinely dismissed and its readers and writers so routinely shamed. If Regis seems at times to protest too much, it’s probably just that she knew her choice of subject would be met with skepticism, if not derision, and not just by her academic colleagues. (I expect that more recent scholarship is less defensive, as genre fiction and popular culture more generally have become increasingly familiar parts of the academic landscape. Eric Selinger and Sarah Frantz’s collection New Approaches to Popular Romance Fiction, which came out in 2012, is also on my reading list; I’ll be curious to see if I’m right that the tone has changed.) Alternatively, you could argue (as I have seen done) that romance, like all genres, comes in both “high” and “low” — or literary and popular — versions.** There’s still a kind of hierarchy, but now you’re separating out those who “transcend the genre” (to use the phrase Ian Rankin hates when applied to crime fiction) from those who happily take their place within it. No direct comparisons are called for, then, and Heyer or Chase (or choose your preferred exemplars) get considered more or less on their own terms. I still think the larger category (the one being subdivided into high and low forms) conflates too many different kinds of things, and the end result can be condescending — it implies, or could, that the serious stuff is going on in some sense over the heads of both readers and writers of the popular incarnations of the genre, or that those who really take themselves and their work seriously will aim at that transcendent kind. But at least this approach doesn’t pretend all novels organized around love and marriage are the same kind of books.

Alternatively, you could argue (as I have seen done) that romance, like all genres, comes in both “high” and “low” — or literary and popular — versions.** There’s still a kind of hierarchy, but now you’re separating out those who “transcend the genre” (to use the phrase Ian Rankin hates when applied to crime fiction) from those who happily take their place within it. No direct comparisons are called for, then, and Heyer or Chase (or choose your preferred exemplars) get considered more or less on their own terms. I still think the larger category (the one being subdivided into high and low forms) conflates too many different kinds of things, and the end result can be condescending — it implies, or could, that the serious stuff is going on in some sense over the heads of both readers and writers of the popular incarnations of the genre, or that those who really take themselves and their work seriously will aim at that transcendent kind. But at least this approach doesn’t pretend all novels organized around love and marriage are the same kind of books. I got a bit snippy with the tweeters from Oxford World’s Classics a couple of days ago. Poor things: they were just doing their job, spreading some news about great books and trying to get people to click through and read it. How could they know that I was already feeling grumpy, for reasons quite beyond their control, and that this particular gimmick pushes my buttons on a good day?

I got a bit snippy with the tweeters from Oxford World’s Classics a couple of days ago. Poor things: they were just doing their job, spreading some news about great books and trying to get people to click through and read it. How could they know that I was already feeling grumpy, for reasons quite beyond their control, and that this particular gimmick pushes my buttons on a good day? But (and you knew it was coming, right?) if for some absurd reason I absolutely had to choose, not which novelist is in any absolute sense “the greatest” but whose team to play on, it would be Brontë all the way — and I say that having only just enjoyed Pride and Prejudice entirely and absolutely for about the 50th time. We’ve just started working our way through Jane Eyre in the 19th-century fiction class and what a thrill it is. I know it’s a cliche to associate the Brontës with the moors, but it does feel as if a fresh, turbulent breeze is rushing through, stirring things up and bringing with it a longing for wide open spaces. The freedom and intensity of Jane’s voice, the urgency of her feelings, and of her demands — for love, for justice, for liberty — it’s exhilarating! I brought some excerpts from contemporary reviews to class today to demonstrate the shock and outrage with which some 19th-century critics received the novel: it’s striking how much the very qualities that enraged and terrified them are the same ones that make so many of us want to cheer Jane on. By the end we know that we should not have allied ourselves so readily with Jane’s violent rebellion, and we may even be equivocal about the conclusion to her story, but I think it’s impossible to read the novel and not be wholly caught up in her fight to define and then live on her own terms.

But (and you knew it was coming, right?) if for some absurd reason I absolutely had to choose, not which novelist is in any absolute sense “the greatest” but whose team to play on, it would be Brontë all the way — and I say that having only just enjoyed Pride and Prejudice entirely and absolutely for about the 50th time. We’ve just started working our way through Jane Eyre in the 19th-century fiction class and what a thrill it is. I know it’s a cliche to associate the Brontës with the moors, but it does feel as if a fresh, turbulent breeze is rushing through, stirring things up and bringing with it a longing for wide open spaces. The freedom and intensity of Jane’s voice, the urgency of her feelings, and of her demands — for love, for justice, for liberty — it’s exhilarating! I brought some excerpts from contemporary reviews to class today to demonstrate the shock and outrage with which some 19th-century critics received the novel: it’s striking how much the very qualities that enraged and terrified them are the same ones that make so many of us want to cheer Jane on. By the end we know that we should not have allied ourselves so readily with Jane’s violent rebellion, and we may even be equivocal about the conclusion to her story, but I think it’s impossible to read the novel and not be wholly caught up in her fight to define and then live on her own terms. In a way, this post is also about “this week in my classes,” as it is prompted by the serendipitous convergence of my current reading around questions we’ve been discussing since we started working on Carol Shields’ Unless in my section of Intro to Lit. In our first session on the novel, I give some introductory remarks about Shields — a life and times overview, and then some suggestions about themes that interested her, especially in relation to Unless. One of the things I pointed out is that she also wrote a biography of Jane Austen; in an interview, Shields said “Jane Austen is important to me because she demonstrates how large narratives can occupy small spaces.” We come to Shields right after working through Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, so I also bring up Woolf’s pointed remark: “This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing room.” Both Shields and Woolf are thinking about the relationship between scale and significance, and both of them are drawing our attention to the ways assumptions about what matters — in literature, particularly, since that’s their primary context — have historically been gendered.

In a way, this post is also about “this week in my classes,” as it is prompted by the serendipitous convergence of my current reading around questions we’ve been discussing since we started working on Carol Shields’ Unless in my section of Intro to Lit. In our first session on the novel, I give some introductory remarks about Shields — a life and times overview, and then some suggestions about themes that interested her, especially in relation to Unless. One of the things I pointed out is that she also wrote a biography of Jane Austen; in an interview, Shields said “Jane Austen is important to me because she demonstrates how large narratives can occupy small spaces.” We come to Shields right after working through Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, so I also bring up Woolf’s pointed remark: “This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing room.” Both Shields and Woolf are thinking about the relationship between scale and significance, and both of them are drawing our attention to the ways assumptions about what matters — in literature, particularly, since that’s their primary context — have historically been gendered. Reta’s redrafting is disrupted by her editor, an officious American (of course! Unless is a Canadian novel, after all) named Arthur Springer who has even bigger plans for Thyme in Bloom, which (significantly) he proposes she retitle simply Bloom. His idea is that Alicia should fade into the background while Roman emerges as the “moral center” of the novel. This, he insists, is necessary for the novel to graduate from “popular fiction” to “quality fiction.” He also proposes that Reta retreat behind her initials: she will become R. R. Summers (“Winters” is her husband’s surname). This way her new (“quality”) book can’t possibly be associated with her, or with her earlier (“popular”) novel.

Reta’s redrafting is disrupted by her editor, an officious American (of course! Unless is a Canadian novel, after all) named Arthur Springer who has even bigger plans for Thyme in Bloom, which (significantly) he proposes she retitle simply Bloom. His idea is that Alicia should fade into the background while Roman emerges as the “moral center” of the novel. This, he insists, is necessary for the novel to graduate from “popular fiction” to “quality fiction.” He also proposes that Reta retreat behind her initials: she will become R. R. Summers (“Winters” is her husband’s surname). This way her new (“quality”) book can’t possibly be associated with her, or with her earlier (“popular”) novel. One of them is Daniel Deronda, which I’ve just finished reading with my graduate students. This novel is famously bifurcated between Gwendolen’s story (a highly personal, small-scale drama) — and Daniel’s (which starts out on a similarly domestic scale but opens out into a potentially epic, world-historical story). Is Gwendolen condemned to insignificance when she is left behind to suffer at home while Daniel goes off to (perhaps) found a nation? The literal scale of Eliot’s treatment of Gwendolen is not belittling: she gets at least half the huge novel to herself, after all. Perhaps this novel insists, formally, on an equivalence between two kinds of significance, one of which occupies a small space. Or perhaps what’s significant is Gwendolen’s discovery of her own insignificance. “Could there be a slenderer, more insignificant thread in human history,” asks the narrator,

One of them is Daniel Deronda, which I’ve just finished reading with my graduate students. This novel is famously bifurcated between Gwendolen’s story (a highly personal, small-scale drama) — and Daniel’s (which starts out on a similarly domestic scale but opens out into a potentially epic, world-historical story). Is Gwendolen condemned to insignificance when she is left behind to suffer at home while Daniel goes off to (perhaps) found a nation? The literal scale of Eliot’s treatment of Gwendolen is not belittling: she gets at least half the huge novel to herself, after all. Perhaps this novel insists, formally, on an equivalence between two kinds of significance, one of which occupies a small space. Or perhaps what’s significant is Gwendolen’s discovery of her own insignificance. “Could there be a slenderer, more insignificant thread in human history,” asks the narrator, Neither of these novels, however, whatever their differences, feels in any way light, despite the intimacy of their core casts of characters. It’s the treatment, not the subject, that gives literary significance, isn’t it? Austen’s novels don’t feel trite even though viewed narrowly they are “just” about a handful of “ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant but confined houses” (in Charlotte Bronte’s words) — because her love stories are also stories about values and class structures and social changes with far-reaching effects. When Isabel Archer accepts Gilbert Osmond’s proposal, it feels large because James has imbued Isabel’s choices with philosophical consequence: her decision isn’t just to marry or not to marry, but about how to use her freedom, and about what to value and how to value herself. These are personal questions but also abstract ones, and so the small space of her individual life occupies a large narrative (by which I don’t mean, though I could, just a long book).

Neither of these novels, however, whatever their differences, feels in any way light, despite the intimacy of their core casts of characters. It’s the treatment, not the subject, that gives literary significance, isn’t it? Austen’s novels don’t feel trite even though viewed narrowly they are “just” about a handful of “ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant but confined houses” (in Charlotte Bronte’s words) — because her love stories are also stories about values and class structures and social changes with far-reaching effects. When Isabel Archer accepts Gilbert Osmond’s proposal, it feels large because James has imbued Isabel’s choices with philosophical consequence: her decision isn’t just to marry or not to marry, but about how to use her freedom, and about what to value and how to value herself. These are personal questions but also abstract ones, and so the small space of her individual life occupies a large narrative (by which I don’t mean, though I could, just a long book). I have been thinking that this constellation of questions (not really any answers) is relevant to the discussions about why, say, Jonathan Franzen’s novels about family and private life get treated as more significant than some other books that are about similar topics. Gender may well be part of the explanation, but it would be disingenuous to pretend we don’t know that some books by both men and women simply do more with their material than others, and that that scale — the scale of meaning, of treatment — is ultimately where literary significance lies. But this post has gone on long enough without really arriving anywhere in particular, so that’s probably as good a place to stop as any.

I have been thinking that this constellation of questions (not really any answers) is relevant to the discussions about why, say, Jonathan Franzen’s novels about family and private life get treated as more significant than some other books that are about similar topics. Gender may well be part of the explanation, but it would be disingenuous to pretend we don’t know that some books by both men and women simply do more with their material than others, and that that scale — the scale of meaning, of treatment — is ultimately where literary significance lies. But this post has gone on long enough without really arriving anywhere in particular, so that’s probably as good a place to stop as any.