This was my favorite moment in Miranda July’s All Fours:

This was my favorite moment in Miranda July’s All Fours:

But this was no good, this line of thought. This was the thinking that had kept every woman from her greatness. There did not have to be an answer to the question why: everything important started out mysterious and this mystery was like a great sea you had to be brave enough to cross. How many times had I turned back at the first ripple of self-doubt? You had to withstand a profound sense of wrongness if you ever wanted to get somewhere new. So far each thing I had done in Monrovia was guided by a version of me that had never been in charge before. A nitwit? A madwoman? Probably. But my more seasoned parts just had to be patient, hold their tongues—their many and sharp tongues—and give this new girl a chance.

Staring down self-doubt! Daring to cross the sea of mystery to change your life! Overcoming that profound sense of wrongness that creates so much fear and inertia! Shutting up the inner voices that keep you from making the radical change you think you need to flourish! That’s what I imagined All Fours would be about: I thought it would be (because this is how it was marketed and also received, or that was my impression) an inspiring novel about aging, a madcap romp through the perils but also perhaps the promises of menopause, etc. etc. I knew it would be a bit “out there” for me, but I liked the idea of a kind of exuberant “fuck you!” to becoming an old(er) woman.

All Fours is all of these things, sort of, or some of the time, but it is also absurd, tedious, and unconvincing. Most of the way through it I was wavering between being amused and being annoyed. That bit I quoted is on page 51 and the novel is over 300 pages, so that’s a long time to be so ambivalent, and by the end annoyance had definitely won out.

I am quite willing to believe that my disgruntled reaction was my own fault—mine and the marketers’. Much as I disavow on principle that protagonists should be “relatable,” you can tell from what I’ve already said in this post that I decided to read this book for personal reasons: that I was hoping it would in some way resonate with my own experiences of being a woman getting older. Not that there’s anything wrong with that! That’s one of the gifts fiction has to offer, sometimes: illumination, insight, understanding, including of ourselves. But this woman, the woman in All Fours? I didn’t understand her at all, and I certainly didn’t relate to her. Is she a nitwit? A madwoman? Both, IMHO. The things she wants, the things she does, made no sense to me. And I don’t think that’s just because she is nothing like me in her values or behavior or priorities or vocabulary or anything else: I just didn’t believe in her as a character (which is a bit funny, I suppose, as I gather All Fours is more or less autofiction). The novel did not make me care what happened to her. Was this because I had started the novel expecting a connection that, to be fair, the novel itself never promised me?

I realize I am being vague about the specifics of the novel. It is a kind of road trip novel, except that instead of traveling across the country the narrator stops basically in the next town over, rents a hotel room, redecorates it (?), stays there, and starts a sexual relationship with a married guy named Davey who works at Hertz but dreams of being a hip hop dancer. The sex is pretty graphic but I’ve been reading romance novels for 15 years now so nothing about that was particularly shocking except that in romance novels the relationship is usually the point and here the point of all the sex is . . . I’m not sure, exactly, but I am pretty sure (though how would I know, I guess?) that the narrator thinks about sex and talks about sex and places more importance on sex than a lot of people. Certainly I have never had conversations like the ones she has with her friends with any of my own friends! It would just never happen—and I’m pretty sure that’s fine, it isn’t a symptom that we or our friendships are inadequate or repressed or inauthentic.

I did pick up that All Fours is “actually” about less literal things, like desire and freedom and expression and creativity. Those are good things to care about. I liked this bit, about a dance the narrator decides to choreograph (if that’s the right word) and record as a gesture and invitation for Davey after their initial fling has ended:

This dance had to work because generally, going forward, things would not work out, disappointment would reign. My grandmother knew this, and her daughter. Everyone older knew. It was a devastating secret we kept from young people. We didn’t want to ruin their fun and also it was embarrassing; they couldn’t imagine a reality this bad so we let them think our lives were just like theirs, only older. The only honest dance was one that surrendered to this weight without pride: I would die for you and . . . I will die anyway. You can do that with dance, say things that are inconceivable, inexpressible, just by struggling forward on hands and knees, ass prone.

Well, I liked it until “ass prone.” She seems allergic to earnestness, this woman, but also addicted to shock, or attempts at shocking. We get it: you’re cool, you swear, you don’t conform.

Annoyance won out, as I said.

If you’ve read All Fours, I’d love to know what you thought. If I had just accepted the character as her own reckless, exuberant, sexy self, is there a good novel there I would have read instead of the one I ultimately found so bafflingly tedious?

I was so tired, but the mess on my bed—the same congestion into which I had nightly crawled without noticing—was suddenly intolerable to me. I yanked at the sheet and the motion sent everything to the carpet. I lifted the sheet with two hands and it billowed slowly back down, and as it did I felt some otherworldly possibility open up inside myself. I picked up one of the pillows from the floor and placed it back on the bed, smoothed the sheet down to make a flat, empty expanse. I stood looking at the bed and breathing. It isn’t something I ever told anyone—how could you say this?—but the lift and descent of that sheet, the air inside it, the peace when it settled, showed me what I wanted. I knew it in that moment, but it took years to find it.

I was so tired, but the mess on my bed—the same congestion into which I had nightly crawled without noticing—was suddenly intolerable to me. I yanked at the sheet and the motion sent everything to the carpet. I lifted the sheet with two hands and it billowed slowly back down, and as it did I felt some otherworldly possibility open up inside myself. I picked up one of the pillows from the floor and placed it back on the bed, smoothed the sheet down to make a flat, empty expanse. I stood looking at the bed and breathing. It isn’t something I ever told anyone—how could you say this?—but the lift and descent of that sheet, the air inside it, the peace when it settled, showed me what I wanted. I knew it in that moment, but it took years to find it. It wasn’t always clear to me as I read the novel why it had the specific pieces in it that it did (and of course I have not itemized them all here, though it is not a plot-heavy book). Sometimes when I’m reading a novel, even for the first time, I feel a gathering sense of its unity as I go along, of what holds it together for me. Other times if I work at it for a bit patterns emerge—sometimes, this happens while I am writing about it here! It’s likely that if I reread Stone Yard Devotional the ideas that connect its various elements would become clearer: I expect they would, because the novel feels so deliberate, so thoughtful. What did hold it together for me was its tone, or voice. I liked the way the narrator thought and talked. Often she leads herself, and thus us, along an unassuming narrative thread until she arrives somewhere quietly meaningful. Here’s an example:

It wasn’t always clear to me as I read the novel why it had the specific pieces in it that it did (and of course I have not itemized them all here, though it is not a plot-heavy book). Sometimes when I’m reading a novel, even for the first time, I feel a gathering sense of its unity as I go along, of what holds it together for me. Other times if I work at it for a bit patterns emerge—sometimes, this happens while I am writing about it here! It’s likely that if I reread Stone Yard Devotional the ideas that connect its various elements would become clearer: I expect they would, because the novel feels so deliberate, so thoughtful. What did hold it together for me was its tone, or voice. I liked the way the narrator thought and talked. Often she leads herself, and thus us, along an unassuming narrative thread until she arrives somewhere quietly meaningful. Here’s an example: Stackhouse was no poet, no artist, and his literary tastes were unsophisticated. But he wrote for himself, not posterity, and he valued the notebook enough to fill more than three hundred pages, and to invite friends and family to make their notes in it too. His observations might be of consequence to no-one but himself, but isn’t it a happy thought that such documents can survive for centuries, intimate memorials to their owners’ preoccupations—unremarkable, hardly read, yet every one unique?

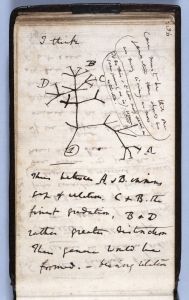

Stackhouse was no poet, no artist, and his literary tastes were unsophisticated. But he wrote for himself, not posterity, and he valued the notebook enough to fill more than three hundred pages, and to invite friends and family to make their notes in it too. His observations might be of consequence to no-one but himself, but isn’t it a happy thought that such documents can survive for centuries, intimate memorials to their owners’ preoccupations—unremarkable, hardly read, yet every one unique? My epigraph for this post comes from the chapter on common-place books; there is also one on seafaring logs and one on the remarkable Visboek, or Fishbook, created by the Dutchman Adriaen Coenen in the 1570s. A chapter on travelers’ notebooks highlights Patrick Leigh Fermor and Bruce Chatwin; one on mathematics of course focuses on Newton. The most famous naturalist to keep notebooks was Charles Darwin, and Allen’s remarks about his process exemplify the connections he makes throughout the book between writing and thinking:

My epigraph for this post comes from the chapter on common-place books; there is also one on seafaring logs and one on the remarkable Visboek, or Fishbook, created by the Dutchman Adriaen Coenen in the 1570s. A chapter on travelers’ notebooks highlights Patrick Leigh Fermor and Bruce Chatwin; one on mathematics of course focuses on Newton. The most famous naturalist to keep notebooks was Charles Darwin, and Allen’s remarks about his process exemplify the connections he makes throughout the book between writing and thinking: What’s distinctive here, of course, is focusing on notebooks themselves as enabling devices for Darwin’s achievements—Allen draws our attention over and over, as he makes his way through his many topics (including, besides the ones already mentioned, authors’ notebooks, recipe collections, police notebooks, patient diaries, and more) to the importance of the flexibility and portability of notebooks, the opportunities they create for in the moment as well as reflective writing, data collection as well as analysis and synthesis. The simple point that they can be carried with us and require so little else to do this work for us, or to support our work, is what matters: this is what was initially transformative and continues to be endlessly appealing, even in this electronic era. In the chapter on “journaling as self-care” Allen discusses the strong evidence for the value of “expressive writing” for helping to heal trauma (he also touches on the reasons that note-taking by hand seems to be more effective for learning during lectures).

What’s distinctive here, of course, is focusing on notebooks themselves as enabling devices for Darwin’s achievements—Allen draws our attention over and over, as he makes his way through his many topics (including, besides the ones already mentioned, authors’ notebooks, recipe collections, police notebooks, patient diaries, and more) to the importance of the flexibility and portability of notebooks, the opportunities they create for in the moment as well as reflective writing, data collection as well as analysis and synthesis. The simple point that they can be carried with us and require so little else to do this work for us, or to support our work, is what matters: this is what was initially transformative and continues to be endlessly appealing, even in this electronic era. In the chapter on “journaling as self-care” Allen discusses the strong evidence for the value of “expressive writing” for helping to heal trauma (he also touches on the reasons that note-taking by hand seems to be more effective for learning during lectures). Like the Florentine accountants, Renaissance artists and early modern scientists before him,” Allen says, “he’d come to understand his notebook as a crucial tool for the mind, a way to turn intangible thoughts into more concrete written ideas that could more easily be manipulated.” So far so good, but once Carroll’s system becomes popular and highly commercial, and “bullet journaling was everywhere,” Allen starts to get a bit sniffy about it—especially about the “huge online community of bullet journalists who took to social media to celebrate and share their own journals.” “Looking at their lists and journal spreads,” he observes, “one senses less intentionality than a straightforward interest in prettification.” He doesn’t seem to approve of the way bullet journaling “fits neatly into the perennially irritating self-help genre,” and “yes,” he says, “if you follow bullet journalists online, you see many doodled sunflowers next to their things-to-do lists.” But, he concedes, “there is something substantial” there nonetheless. Given that he goes on to once more affirm that Carroll’s systematic use of notebooks belongs in the story he’s telling and even, as he notes, has a unique place, as Carroll is rare in himself thinking of the notebook “as a tool, wonder[ing] how it actually works,” I didn’t see why he got so grudging about it there for a while. Michael of Rhodes was interested in “prettification” too, as was the fishbook guy, after all!

Like the Florentine accountants, Renaissance artists and early modern scientists before him,” Allen says, “he’d come to understand his notebook as a crucial tool for the mind, a way to turn intangible thoughts into more concrete written ideas that could more easily be manipulated.” So far so good, but once Carroll’s system becomes popular and highly commercial, and “bullet journaling was everywhere,” Allen starts to get a bit sniffy about it—especially about the “huge online community of bullet journalists who took to social media to celebrate and share their own journals.” “Looking at their lists and journal spreads,” he observes, “one senses less intentionality than a straightforward interest in prettification.” He doesn’t seem to approve of the way bullet journaling “fits neatly into the perennially irritating self-help genre,” and “yes,” he says, “if you follow bullet journalists online, you see many doodled sunflowers next to their things-to-do lists.” But, he concedes, “there is something substantial” there nonetheless. Given that he goes on to once more affirm that Carroll’s systematic use of notebooks belongs in the story he’s telling and even, as he notes, has a unique place, as Carroll is rare in himself thinking of the notebook “as a tool, wonder[ing] how it actually works,” I didn’t see why he got so grudging about it there for a while. Michael of Rhodes was interested in “prettification” too, as was the fishbook guy, after all! —even to care for the sick. With it, we can come to know ourselves better, appreciate the good, put the bad in perspective, and live fuller lives.

—even to care for the sick. With it, we can come to know ourselves better, appreciate the good, put the bad in perspective, and live fuller lives. Last week in my classes it was Reading Week, a.k.a. the February “study break.” Although overall this term has not been nearly as hectic as last term, I was still grateful for the chance to ease up. Work is tiring. Winter is tiring. Grieving is tiring (yes, still). It doesn’t help that I continue to wake up a lot at night with shoulder pain, something I have been trying to fix for years now. (I am getting closer, I think! I am working with an orthopedist who seems pretty confident about what needs doing, although we are waiting for an ultrasound to confirm that the issue is my rotator cuff.)

Last week in my classes it was Reading Week, a.k.a. the February “study break.” Although overall this term has not been nearly as hectic as last term, I was still grateful for the chance to ease up. Work is tiring. Winter is tiring. Grieving is tiring (yes, still). It doesn’t help that I continue to wake up a lot at night with shoulder pain, something I have been trying to fix for years now. (I am getting closer, I think! I am working with an orthopedist who seems pretty confident about what needs doing, although we are waiting for an ultrasound to confirm that the issue is my rotator cuff.)

The one other book I got all the way through last week was actually an audiobook: my hold on Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain came in, and it proved truly gripping, surprisingly so given that I knew a fair amount about the whole story from various other sources (including the harrowing series Dopesick). I was so caught up in it that I spent longer hours than usual working on my current jigsaw puzzle—which I think contributed to my shoulder pain somehow, so that was a weird confluence as it had me thinking a lot about how tempting the promise of relief would be even for chronic pain as relatively mild as mine. Of course the whole story is also infuriating and outrageous and horrific, and perhaps it would have been more calming to stick to my usual, more benign, program of literary podcasts!

The one other book I got all the way through last week was actually an audiobook: my hold on Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain came in, and it proved truly gripping, surprisingly so given that I knew a fair amount about the whole story from various other sources (including the harrowing series Dopesick). I was so caught up in it that I spent longer hours than usual working on my current jigsaw puzzle—which I think contributed to my shoulder pain somehow, so that was a weird confluence as it had me thinking a lot about how tempting the promise of relief would be even for chronic pain as relatively mild as mine. Of course the whole story is also infuriating and outrageous and horrific, and perhaps it would have been more calming to stick to my usual, more benign, program of literary podcasts! and that timing may well have been the real reason for my middling reaction to it. So far I am enjoying it just fine; we’ll see if when I get to the end this time I feel like reading on in the series.

and that timing may well have been the real reason for my middling reaction to it. So far I am enjoying it just fine; we’ll see if when I get to the end this time I feel like reading on in the series. It’s not that the topic of my classes this week is uncertainty, exactly, or that there is anything particularly uncertain about this week—although I suppose that depends on where you’re looking, as nationally and globally there is plenty of unease to go around, while on campus, as the university shapes and shares its plans for coping with a massive budget shortfall (created in large part by heavy-handed federal decisions about international students, on whom universities have unfortunately come to depend because of decades of inadequate provincial funding) we are all wondering just how bad it will get. These are the external contexts for my classes, but by and large I try not to focus on them when I’m actually in the classroom, where persisting with what we find interesting and worthwhile to talk about seems like one way to make sure we uphold our values in the face of all of this.

It’s not that the topic of my classes this week is uncertainty, exactly, or that there is anything particularly uncertain about this week—although I suppose that depends on where you’re looking, as nationally and globally there is plenty of unease to go around, while on campus, as the university shapes and shares its plans for coping with a massive budget shortfall (created in large part by heavy-handed federal decisions about international students, on whom universities have unfortunately come to depend because of decades of inadequate provincial funding) we are all wondering just how bad it will get. These are the external contexts for my classes, but by and large I try not to focus on them when I’m actually in the classroom, where persisting with what we find interesting and worthwhile to talk about seems like one way to make sure we uphold our values in the face of all of this. The main thing I’m thinking about, however, is not so much “what is the meaning of Villette?” (though if you have a favorite essay or theory about it, I’d love to know!) as “what is the role of uncertainty in pedagogy?” I don’t think of myself as a particularly authoritarian teacher, but in general I think it makes sense to acknowledge that I am a teacher because of my expertise; shouldn’t I act and talk as if I know what I am talking about? On the other hand, I don’t think any interpretation is definitive; if it were, our whole discipline would operate completely differently! I’m always so amused by Thurber’s story “The Macbeth Murder Mystery,” which concludes, tongue in cheek, with its wry narrator promising to “solve” Hamlet. Literature can’t be “solved”! Books worth paying attention to are layered or multifaceted; they look different or mean differently depending on how we approach them. I often explain literary interpretation to my first-year students with an analogy to the transparencies used to teach anatomy: each question or approach draws our attention to specific features. Just as all the parts and systems of the body cohere, interpretations have to be compatible to the extent that they can’t ignore or contradict facts about the text, but they do not replace each other or rule each other out. This means, of course, that it is fine that the articles I’ve mentioned illuminate issues in Villette without satisfying every question I have about the novel.

The main thing I’m thinking about, however, is not so much “what is the meaning of Villette?” (though if you have a favorite essay or theory about it, I’d love to know!) as “what is the role of uncertainty in pedagogy?” I don’t think of myself as a particularly authoritarian teacher, but in general I think it makes sense to acknowledge that I am a teacher because of my expertise; shouldn’t I act and talk as if I know what I am talking about? On the other hand, I don’t think any interpretation is definitive; if it were, our whole discipline would operate completely differently! I’m always so amused by Thurber’s story “The Macbeth Murder Mystery,” which concludes, tongue in cheek, with its wry narrator promising to “solve” Hamlet. Literature can’t be “solved”! Books worth paying attention to are layered or multifaceted; they look different or mean differently depending on how we approach them. I often explain literary interpretation to my first-year students with an analogy to the transparencies used to teach anatomy: each question or approach draws our attention to specific features. Just as all the parts and systems of the body cohere, interpretations have to be compatible to the extent that they can’t ignore or contradict facts about the text, but they do not replace each other or rule each other out. This means, of course, that it is fine that the articles I’ve mentioned illuminate issues in Villette without satisfying every question I have about the novel. Villette, on the other hand, feels uncertain by design. It is destabilizing. Our confusion feels like part of the point. Maybe that is the underlying unity of the novel! Maybe there is no ‘right’ way for Lucy to be, to act, to love, to live, and so the novel, by immersing ourselves in her struggles, is just replicating them formally. “Who are you, Miss Snowe?” demands Ginevra Fanshawe at one point, with exasperation: aren’t we asking the same question, right to the very end? Why should unity be the end point, even for a novel that seems to be some kind of a Bildungsroman? I do wonder, though, why I am willing to give Brontë so much more credit than Braddon for the artfulness of her uncertainty. One factor is probably that there is so much evidence of design in Villette, if if I’m not sure what the patterns mean: all the buried (or not!) nuns, for example, and their tendency to show up when Lucy is most emotional; the recurrent imagery of storms and shipwrecks; the emphasis on surveillance, discipline, and self-control; the proliferation, almost to excess, of foil characters for Lucy, from little Polly to Vashti. At every moment of the novel I feel sure there is something meaningful going on.

Villette, on the other hand, feels uncertain by design. It is destabilizing. Our confusion feels like part of the point. Maybe that is the underlying unity of the novel! Maybe there is no ‘right’ way for Lucy to be, to act, to love, to live, and so the novel, by immersing ourselves in her struggles, is just replicating them formally. “Who are you, Miss Snowe?” demands Ginevra Fanshawe at one point, with exasperation: aren’t we asking the same question, right to the very end? Why should unity be the end point, even for a novel that seems to be some kind of a Bildungsroman? I do wonder, though, why I am willing to give Brontë so much more credit than Braddon for the artfulness of her uncertainty. One factor is probably that there is so much evidence of design in Villette, if if I’m not sure what the patterns mean: all the buried (or not!) nuns, for example, and their tendency to show up when Lucy is most emotional; the recurrent imagery of storms and shipwrecks; the emphasis on surveillance, discipline, and self-control; the proliferation, almost to excess, of foil characters for Lucy, from little Polly to Vashti. At every moment of the novel I feel sure there is something meaningful going on. And now, in this low and critical moment, something in Penelope, something which had understood courage and resource and action, though she herself had never been brave or resourceful or active, stirred and shook itself. The pirate woman, Jane Moore, the Aztec girl, Xhalama, the misunderstood Tudor stateswoman and others of their blood, stood by her bed, urging her to save herself . . . and to justify them.

And now, in this low and critical moment, something in Penelope, something which had understood courage and resource and action, though she herself had never been brave or resourceful or active, stirred and shook itself. The pirate woman, Jane Moore, the Aztec girl, Xhalama, the misunderstood Tudor stateswoman and others of their blood, stood by her bed, urging her to save herself . . . and to justify them. Terry is a great addition to Penelope’s household and her life: he takes excellent care of her, even giving her massages when she is stiff and tired from typing. Once again things seem to be going well for Penelope, but Terry’s presence kindles gossip. When he confronts her about it, he shocks her by adding “I happen to be terribly in love with you.” He kisses her, “and Penelope was lost.” She agrees that they should marry. Hooray! you might think: our mousy heroine has found love. But before the chapter closes, the novel shifts gears, giving us a glimpse of the real Terry in his “expression of calculating triumph”: “After all, one likes six months of hard labour to bear some result.”

Terry is a great addition to Penelope’s household and her life: he takes excellent care of her, even giving her massages when she is stiff and tired from typing. Once again things seem to be going well for Penelope, but Terry’s presence kindles gossip. When he confronts her about it, he shocks her by adding “I happen to be terribly in love with you.” He kisses her, “and Penelope was lost.” She agrees that they should marry. Hooray! you might think: our mousy heroine has found love. But before the chapter closes, the novel shifts gears, giving us a glimpse of the real Terry in his “expression of calculating triumph”: “After all, one likes six months of hard labour to bear some result.” —and gets ideas. “If we are part of all we have been,” comments the narrator, “how much more are we part of all we have made?” I loved this moment, which picks up on an idea that has been central to a lot of my own work on women’s writing. “Lives do not serve as models,” Carolyn Heilbrun wrote in Writing A Woman’s Life; “only stories do that.” For Penelope, the stories she has written quite literally empower her—and then it is “over and done with, and Penelope was no more a clever, cunning, ruthless creature, but a gentle little woman with a conscience.”

—and gets ideas. “If we are part of all we have been,” comments the narrator, “how much more are we part of all we have made?” I loved this moment, which picks up on an idea that has been central to a lot of my own work on women’s writing. “Lives do not serve as models,” Carolyn Heilbrun wrote in Writing A Woman’s Life; “only stories do that.” For Penelope, the stories she has written quite literally empower her—and then it is “over and done with, and Penelope was no more a clever, cunning, ruthless creature, but a gentle little woman with a conscience.”  It has been a long time since I worked through Elizabeth Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë with a class. In fact, the last time I did so was the first year I began this blog series, in the

It has been a long time since I worked through Elizabeth Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë with a class. In fact, the last time I did so was the first year I began this blog series, in the

We started with Sherlock Holmes in Mystery & Detective Fiction this week. I’m not the world’s biggest Holmes enthusiast, but as I have documented here often enough over the years, I greatly appreciate The Hound of the Baskervilles, which we will get to on Wednesday. Today was “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” with its famous “interpret everything about a man from his hat” set piece, and “A Scandal in Bohemia,” with Irene Adler (“To Sherlock Holmes, she was always the woman”). These are good ones: I enjoy them. I think the class is going fine so far: it ought to be, considering how often I’ve taught it now! One thing I’m noticing is spotty attendance. It isn’t making me rethink my long-ago decision not to give grades for attendance, but it gives me food for thought in other ways, as this seems to be a trend in this class in recent years. Perhaps it’s because the course is an elective for pretty much everyone taking it, so they give it lower priority than their other obligations? Is it that students who don’t take a lot of English classes assume the pertinent course content is exclusively in the “textbooks” (what we call the “readings”!) and don’t expect our class time to offer much “value added”? I know that in some subjects lectures often do simply reiterate content in that way, but of course I’m not standing there rehearsing the plot of The Moonstone. Anyway, I try not to take it personally but it rather baffles me: what is the point in signing up to “take” a class but then not really “taking” it? Sure, you can read on your own (or, sigh, just search online summaries and call that “keeping up”), but unless all you are after is the course credit, aren’t you skipping the good part, not to mention the part you are actually paying for?

We started with Sherlock Holmes in Mystery & Detective Fiction this week. I’m not the world’s biggest Holmes enthusiast, but as I have documented here often enough over the years, I greatly appreciate The Hound of the Baskervilles, which we will get to on Wednesday. Today was “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” with its famous “interpret everything about a man from his hat” set piece, and “A Scandal in Bohemia,” with Irene Adler (“To Sherlock Holmes, she was always the woman”). These are good ones: I enjoy them. I think the class is going fine so far: it ought to be, considering how often I’ve taught it now! One thing I’m noticing is spotty attendance. It isn’t making me rethink my long-ago decision not to give grades for attendance, but it gives me food for thought in other ways, as this seems to be a trend in this class in recent years. Perhaps it’s because the course is an elective for pretty much everyone taking it, so they give it lower priority than their other obligations? Is it that students who don’t take a lot of English classes assume the pertinent course content is exclusively in the “textbooks” (what we call the “readings”!) and don’t expect our class time to offer much “value added”? I know that in some subjects lectures often do simply reiterate content in that way, but of course I’m not standing there rehearsing the plot of The Moonstone. Anyway, I try not to take it personally but it rather baffles me: what is the point in signing up to “take” a class but then not really “taking” it? Sure, you can read on your own (or, sigh, just search online summaries and call that “keeping up”), but unless all you are after is the course credit, aren’t you skipping the good part, not to mention the part you are actually paying for?

I pretended everything would be okay because it seemed impossible to always be saying goodbye. To blueberries. To the ocean. To ravens. To pelicans and plovers. To the cormorants. To the sunlight on the living room wall at four o’clock. To the sound of you in the next room.

I pretended everything would be okay because it seemed impossible to always be saying goodbye. To blueberries. To the ocean. To ravens. To pelicans and plovers. To the cormorants. To the sunlight on the living room wall at four o’clock. To the sound of you in the next room.