2012 seems to have been a particularly rich and rewarding reading year – also, a particularly maddening and occasionally stultifying one. I suppose what I’m saying is that it was a reading year like any other one! As always, some books stand out, though sometimes as much for the challenge and gratification I found in writing about them, or for the conversations that my posts generated, as for the reading experience in itself. As is traditional, here’s a look back at the highlights.

Book of the Year:

Book of the Year:

Molly Peacock, The Paper Garden. This book drew me to it by its physical beauty and turned out to be the right book for me at the right moment. This is the kind of serendipitous discovery that seems unlikely to happen except in a real (and well-curated) bookstore: for reasons I explain in my original post, it’s unlikely I would have deliberately sought out a book like this. I’m so glad I succumbed to its charms. My review is one of my favorite pieces of my own writing from 2012.

Other books I’m particularly glad I read or wrote about:

Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies. Well, of course. But then, it’s no small feat to follow up the brilliant Wolf Hall with something equally brilliant. I did think, as I read it, that it would have been just a teensy bit more exciting if Mantel–who is a prose virtuoso–had decided to approach each novel in her Cromwell trilogy in a different way, a different voice. But the close third-person narration is just as compelling and even more morally complex here than in the first volume, and my expectations are now sky-high for the concluding one.

T. H. White, The Once and Future King. Another surprise: I don’t “do” fantasy any more than I “do” the 18th century, and yet from the first page I loved this novel. I can’t think of another novel I’ve read recently–not just in 2012 but in several years–that had this much emotional range. For once, the adjective “Dickensian” doesn’t seem out of place, as this really is fiction written to change how you think as well as to make you laugh and cry.

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary. Along with St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels, Madame Bovary was the most thought-provoking read of 2012 for me as a critic, because it was the least congenial for me as a reader. Even while I couldn’t deny its mastery, I couldn’t help but decry its grim and limited worldview. Yes, we can all sometimes be Emma Bovary, but most of us will surely never be exclusively so self-absorbed or self-deceived. If we are, shame on us, and we need books that help us out of that moral rut even more.

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina. I’ve only just finished Anna Karenina so I’m still thinking about it. I wasn’t swept up in it, but then, limited as my experience with Tolstoy is, I guess that shouldn’t have surprised me: there’s a quality of ruthlessness in his fiction that I’d noticed before.

Edward St. Aubyn, The Patrick Melrose Novels. I abhorred and admired these novels in about equal measure. Actually, I think by the end of At Last admiration had won out, but it was a close thing.

Helen DeWitt, Lightning Rods. Another surprise. I don’t think any author except DeWitt could have pulled this off in a way I would, if not exactly enjoy, at least applaud.

Susan Messer, Grand River and Joy. I was completely absorbed by this novel set in Detroit around the time of the 1967 riot and focusing on tensions “between blacks and Jews but [also] between individual identities and group allegiances, between narrowly-defined protective self-interest and the desire to reach out and make connections.”

J. G. Farrell, The Siege of Krishnapur. I liked this as much as I liked the first in the trilogy, Troubles. If you want to read something truly substantial about Farrell, skip my post and read Dorian Stuber’s essay on him in Open Letters.

Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front. The ultimate novel of the ‘lost generation’: “We are forlorn like children, and experienced like old men, we are crude and sorrowful and superficial–I believe we are lost.”

Books I didn’t much like:

Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea. Meh.

Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier. Hey, it’s my blog, isn’t it?

Low point of my reading year:

George Sand, Indiana. Don’t worry, George: it’s not you, it’s me! Or maybe not.

Books I’m especially looking forward to reading in 2013:

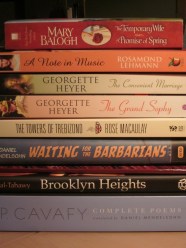

All the ones in my Christmas loot pile, of course. But also:

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. It has been fabulous so far, and my only (lame) excuses for not having persisted are not having committed deliberately enough (I proved to myself with Anna Karenina this month that being busy with other things is no reason not to get through a doorstopper) and its weight: there’s no way you can tuck this volume in your purse for reading at odd moments.

The Singapore Grip. One more in Farrell’s Empire Trilogy, and I’m sure it will be as strange and brilliant and darkly comic as the others.

The rest of the Raj Quartet. I found The Jewel in the Crown engrossing and complex and am keen to make my way through the next volumes.

War and Peace. This has featured in this “to read” list for several years now; maybe 2013 is the year I’ll finally get it done.

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts. This is another book I picked up on my spring trip to Boston and one of the few from that expedition that I haven’t read yet. Wallace Stegner’s Angle of Repose is another, and that’s high on my TBR pile too.

Up next, though, will be Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which is the January book for my local book club, and then Doctor Glas, which is the next read for the Slaves of Golconda.

Notable Posts of 2012:

Finally, it seems worth noting a couple of posts that weren’t exactly reviews but that generated more excitement than is usual in this quiet corner of the internet:

Your book club wants to read Middlemarch? Great idea! I have not forgotten or abandoned the idea of creating the “Middlemarch for Book Club” site I proclaimed so boldly here. In fact, it already exists in skeletal form. I wanted to do it well, though, and thus took my time over it at first, and then I put it on the back burner and then it was the new term. One of my resolutions for 2013 is to build more of it and then start making it available in a ‘beta’ version. It’s not going to be anything too fancy: I’m just using WordPress to set it up. But if people seem to like it and find it valuable, it’s the kind of thing I might eventually seek out some funding for and try to make really good.

How to Read a Victorian Novel. I put this together as part of Molly Templeton’s call for responses to the NYTBR “How-To” issue that seemed to think women didn’t know how to do much of interest beyond cook and raise children. How does that even happen, in 2012? Where are the editors? What are they thinking, when they see a cover graphic like that? Anyway, the resulting tumblr turned into something quite amazing, and it was really energizing to be a part of it. Thanks to a couple of high-profile links to it, this is my most-read post of all time.

Thanks to everyone who read and commented on Novel Readings in 2012. Happy New Year!

If Anna represents the futility of material striving–of seeking lasting happiness through pursuing her own immediate needs–perhaps Levin represents spiritual striving. At any rate, that’s the best I’ve come up with so far as I ponder the relationship between the two major plots of Anna Karenina. In Levin’s epiphanic musings towards the end of the novel, he repeats the words of the peasant Theodore:

If Anna represents the futility of material striving–of seeking lasting happiness through pursuing her own immediate needs–perhaps Levin represents spiritual striving. At any rate, that’s the best I’ve come up with so far as I ponder the relationship between the two major plots of Anna Karenina. In Levin’s epiphanic musings towards the end of the novel, he repeats the words of the peasant Theodore:

I finished Anna Karenina yesterday–or, I should say, I finished Anna Karenina for the first time: it’s so large and complicated, and also so alien, so unfamiliar, to me that I hardly feel I’ve really read it yet. It was an odd, engrossing, and somewhat frustrating experience working my way through it. Despite its sprawl and its episodic character, it felt well built to me, with the two major plots running sometimes in parallel, sometimes intersecting, and always provoking questions about the significance of their juxtaposition. But I felt morally and thematically adrift much of the time, partly (presumably) because I’m new to the novel and there’s a lot of it to take in, and partly (perhaps) because the novel doesn’t work quite the way the big novels I know best work, which is to say, it sets out its characters and its problems without also providing a readerly guide in the form of, say, an intrusive narrator. There’s no friendly companion, no wry moralist, no philosophical or historical commentator–in other words, this is not a novel by Trollope, or Thackeray, or George Eliot. The unifying perspective–the set of ideas that make all the different parts of the novel into a whole–emerges only implicitly, and to me, so far, remains somewhat elusive.

I finished Anna Karenina yesterday–or, I should say, I finished Anna Karenina for the first time: it’s so large and complicated, and also so alien, so unfamiliar, to me that I hardly feel I’ve really read it yet. It was an odd, engrossing, and somewhat frustrating experience working my way through it. Despite its sprawl and its episodic character, it felt well built to me, with the two major plots running sometimes in parallel, sometimes intersecting, and always provoking questions about the significance of their juxtaposition. But I felt morally and thematically adrift much of the time, partly (presumably) because I’m new to the novel and there’s a lot of it to take in, and partly (perhaps) because the novel doesn’t work quite the way the big novels I know best work, which is to say, it sets out its characters and its problems without also providing a readerly guide in the form of, say, an intrusive narrator. There’s no friendly companion, no wry moralist, no philosophical or historical commentator–in other words, this is not a novel by Trollope, or Thackeray, or George Eliot. The unifying perspective–the set of ideas that make all the different parts of the novel into a whole–emerges only implicitly, and to me, so far, remains somewhat elusive. I began my annual look back at 2012 with my small contribution to the Open Letters

I began my annual look back at 2012 with my small contribution to the Open Letters