Because of the Thanksgiving holiday on Monday, my graduate seminar didn’t meet this week. If only Eliot had written her novels in a different order, we could have used that extra time for reading through Middlemarch — always the book for which I like to allow the most weeks because it demands and rewards such luxurious patience. But we are only on The Mill on the Floss, so instead we just delayed our discussion of the second half. Not that The Mill on the Floss doesn’t also demand and reward patient reading! In fact, rereading it has been one of the best parts of the past couple of weeks for me. It still absorbs me, especially as we rush towards the final catastrophe in Books VI and VII. I hope the students feel the same way.

Because of the Thanksgiving holiday on Monday, my graduate seminar didn’t meet this week. If only Eliot had written her novels in a different order, we could have used that extra time for reading through Middlemarch — always the book for which I like to allow the most weeks because it demands and rewards such luxurious patience. But we are only on The Mill on the Floss, so instead we just delayed our discussion of the second half. Not that The Mill on the Floss doesn’t also demand and reward patient reading! In fact, rereading it has been one of the best parts of the past couple of weeks for me. It still absorbs me, especially as we rush towards the final catastrophe in Books VI and VII. I hope the students feel the same way.

My Introduction to Prose and Fiction class, however, has two meetings this week. We have wrapped up our work on essays and are in the middle, now, of our short fiction unit. We read “The Yellow Wallpaper” for Wednesday’s class, and I was reminded all over again what a strange, creepy, brilliant story it is. Though obviously one key thing I wanted us to discuss (which we did) was Gilman’s critique — through her narrator’s sad, horrifying, weirdly comic disintegration (“I got so angry I bit off a little piece [of the bed] at one corner – but it hurt my teeth,” she says, with such disquieting reasonableness!) — of a whole destructive patriarchal system, I also tried to keep some emphasis on literary details, including symbolism (an easy one, in this case), personification, and imagery:

It is dull enough to confuse the eye in following, pronounced enough to constantly irritate and provoke study, and when you follow the lame uncertain curves for a little distance they suddenly commit suicide — plunge off at outrageous angles, destroy themselves in unheard-of contradictions.

The colour is repellent, almost revolting: a smouldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight. It is a dull yet lurid orange in some places, a sickly sulphur tint in others.

All of these vivid details contribute, of course, to our sense of her character and situation: it’s not hard to pick up on the wallpaper, and then the woman she “sees” behind the pattern, as a projection of her entrapment and despair. That’s one reason that the story’s a classic, and that it’s so fun as well as useful to teach: there are subtle details, but as a whole it’s almost as flamboyantly expressive as the wallpaper.

Today in our smaller tutorial my group will be reading a story that is equally artful but far more subtle: Kazuo Ishiguro’s “A Family Supper.” Here, I think, we will have to work much harder to move past our initial impressions of what the story is about, of what details in it are significant and how they add up. Ishiguro is a master of understatement but also of moods and shadows. Despite its innocuous-seeming title, “A Family Supper” has an atmosphere of menace from the opening account of the poisonous fugu fish, and the title itself starts to seem less and less innocent as we learn first of the death of the narrator’s mother (at another seemingly-innocuous supper) and then of a father who killed himself and his whole family to escape the dishonour of his failed business. There isn’t much overt action in the story, and the ending especially feels like an anti-climax. With Ishiguro, though, the conflicts tend to shimmer around the characters, to be represented as much by what they don’t say or do as by what they actually say or do.

Today in our smaller tutorial my group will be reading a story that is equally artful but far more subtle: Kazuo Ishiguro’s “A Family Supper.” Here, I think, we will have to work much harder to move past our initial impressions of what the story is about, of what details in it are significant and how they add up. Ishiguro is a master of understatement but also of moods and shadows. Despite its innocuous-seeming title, “A Family Supper” has an atmosphere of menace from the opening account of the poisonous fugu fish, and the title itself starts to seem less and less innocent as we learn first of the death of the narrator’s mother (at another seemingly-innocuous supper) and then of a father who killed himself and his whole family to escape the dishonour of his failed business. There isn’t much overt action in the story, and the ending especially feels like an anti-climax. With Ishiguro, though, the conflicts tend to shimmer around the characters, to be represented as much by what they don’t say or do as by what they actually say or do.

I’ve been following Dorian’s wonderful series of posts about his short fiction class, and it has got me thinking about the role of leading questions in our teaching — often he comments on what he’s hoping or expecting students to come up with in response to his prompts, for instance. This is not the same as trying to steer them towards one “correct” answer, of course, and the process he describes is intensely familiar to me. There’s no point asking completely open-ended questions that, as far as you know, will get you nowhere in particular in terms of understanding the story in front of you, so we ask leading questions to help our students discover for themselves what we already know is there. The process also models for them the right (meaning most productive) kinds of questions to ask. But at the same time, you want to allow for different readings, for original observations, for the idiosyncrasy of genuine individual engagement. One reason I like to mix in stories I don’t already know well, like “A Family Supper,” is that it is easier for me to back off, to be open-mindedly curious and see where our discussion takes us. I have some ideas about the story’s central themes and how its specific details (the fugu fish, for instance) fit into them — but it’s still somewhat strange to me, and its subtlety means working harder to make something of it. I hope it isn’t too elusive for the students to take an interest in it. (Updated post-tutorial: I think we had quite a good discussion, particularly about the family dynamic in the story and the way both cultural and generational expectations and differences affect it. Some students said they found it frustrating that there’s so little action, or that the conflict feels so unresolved, but I suspect that’s one reason we ended up with so much to say about it — unlike a more plot-driven story, “A Family Supper” forces us to look for meaning in other places.)

Next week it’s “Araby” and then Mansfield’s “The Garden Party,” so back again to established classics. One of my TAs has volunteered to teach the session on “Araby,” which means I get to return to one of my favorite roles in the classroom — being a student again!

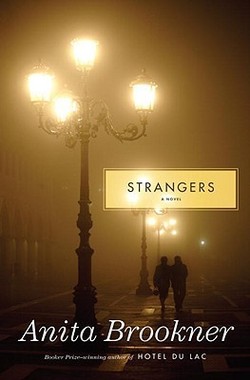

That was one of the dubious endowments of ageing, a conviction that one’s desires had not been met, that there was in fact no reward, and that the way ahead was simply one of endurance.

That was one of the dubious endowments of ageing, a conviction that one’s desires had not been met, that there was in fact no reward, and that the way ahead was simply one of endurance.

My Lady of Cleves is much less ambitious than any of Dunnett’s novels: it is historical fiction as domestic drama, with no pretensions to theories or philosophies about the rise and fall of nations or faiths or civilizations. It is, as a result, much easier reading — and easier writing too, no doubt! Its premise is simple and sweet: that Holbein’s exquisite portraits of Anne, including the miniature that (mis)led Henry VIII into choosing her for his fourth wife, are evidence of a hidden love story between the great artist and his unprepossessing subject. How else, after all, to explain the mismatch between the beauty of his work and the reality of the woman Henry so contemptuously cast aside? Holbein must have seen something his king — coarse, lusty, spoiled — could not, and that something is what the novel creates for us: a woman of quiet dignity, but also strong feeling, held carefully in reserve, a woman who would — if things had gone differently — have made a good, perhaps even a great, queen, but who missed, or was spared, that fate.

My Lady of Cleves is much less ambitious than any of Dunnett’s novels: it is historical fiction as domestic drama, with no pretensions to theories or philosophies about the rise and fall of nations or faiths or civilizations. It is, as a result, much easier reading — and easier writing too, no doubt! Its premise is simple and sweet: that Holbein’s exquisite portraits of Anne, including the miniature that (mis)led Henry VIII into choosing her for his fourth wife, are evidence of a hidden love story between the great artist and his unprepossessing subject. How else, after all, to explain the mismatch between the beauty of his work and the reality of the woman Henry so contemptuously cast aside? Holbein must have seen something his king — coarse, lusty, spoiled — could not, and that something is what the novel creates for us: a woman of quiet dignity, but also strong feeling, held carefully in reserve, a woman who would — if things had gone differently — have made a good, perhaps even a great, queen, but who missed, or was spared, that fate. But it’s Anne who, rightly, holds first place in the novel overall. Barnes makes the lack of dramatic incident in Anne’s life itself dramatic: with the ghost of Anne Boleyn behind her and the tragic spectacle of young Katherine Howard’s fall before her, her relative tranquility seems precious, even if it is maintained through the sacrifice of her most passionate yearnings. I have no idea how much of Barnes’s portrait is based on historical records: her author’s note says that all the comments in the novel about Anne “were in fact made by people who knew and saw her,” but how much we know about Anne herself, as a woman, or about the details of her life before, during, or after her life-changing marriage is beyond my scope. What Barnes does so well, though, is make me believe in her version of Anne: it’s as if (and I know this sounds cliched) the poised woman in the portrait has stepped out of it into the novel.

But it’s Anne who, rightly, holds first place in the novel overall. Barnes makes the lack of dramatic incident in Anne’s life itself dramatic: with the ghost of Anne Boleyn behind her and the tragic spectacle of young Katherine Howard’s fall before her, her relative tranquility seems precious, even if it is maintained through the sacrifice of her most passionate yearnings. I have no idea how much of Barnes’s portrait is based on historical records: her author’s note says that all the comments in the novel about Anne “were in fact made by people who knew and saw her,” but how much we know about Anne herself, as a woman, or about the details of her life before, during, or after her life-changing marriage is beyond my scope. What Barnes does so well, though, is make me believe in her version of Anne: it’s as if (and I know this sounds cliched) the poised woman in the portrait has stepped out of it into the novel.

I have really enjoyed rereading Adam Bede for my graduate seminar over the past two weeks. Though I know the novel reasonably well, I have never spent the kind of dedicated time on it that I have on Middlemarch or The Mill on the Floss — or, for that matter, on

I have really enjoyed rereading Adam Bede for my graduate seminar over the past two weeks. Though I know the novel reasonably well, I have never spent the kind of dedicated time on it that I have on Middlemarch or The Mill on the Floss — or, for that matter, on

We are into our second full week of classes now. I think things are mostly going smoothly, but that’s as much thanks to habit and experience as anything I’ve done particularly effectively in the past week or so. It’s not that anything is going badly — at least, not as far as I can tell. I just feel creaky, and I suppose that’s to be expected after almost nine months out of the classroom.

We are into our second full week of classes now. I think things are mostly going smoothly, but that’s as much thanks to habit and experience as anything I’ve done particularly effectively in the past week or so. It’s not that anything is going badly — at least, not as far as I can tell. I just feel creaky, and I suppose that’s to be expected after almost nine months out of the classroom. My other class this term is my graduate seminar on George Eliot. Here I have a cozy group, just five students, and it really is an entirely different ball game than Intro. Last week I gave an overview lecture on George Eliot to provide some common background, since as usual the students have quite a range of prior experience (this year, from none at all to a bit) reading her work. Then we took a look at some of her most famous essays, including “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists.” We spent some time on the vexed question of whether the essay’s brilliant snark is misogynistic. Since the last time I taught this seminar (in 2010), my own reading has broadened to include

My other class this term is my graduate seminar on George Eliot. Here I have a cozy group, just five students, and it really is an entirely different ball game than Intro. Last week I gave an overview lecture on George Eliot to provide some common background, since as usual the students have quite a range of prior experience (this year, from none at all to a bit) reading her work. Then we took a look at some of her most famous essays, including “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists.” We spent some time on the vexed question of whether the essay’s brilliant snark is misogynistic. Since the last time I taught this seminar (in 2010), my own reading has broadened to include