I can’t believe Reading Week is already two weeks ago — but that’s what it’s always like when we come back. I don’t like to say that it’s all downhill from there, but it does always seem as if the term accelerates, even as the work accumulates. And there are just so many moving parts! All the routine business of class meetings continues, including doing the readings, preparing lecture notes or handouts or worksheets or slides, keeping attendance records, and just plain showing up and going through the whole song and dance number — which is the most fun part, but also the most tiring part. From now until after exams, there’s also a constant flow of assignments in and out, and that means getting topics and instructions up in plenty of time; there are tests to prepare — which has to be done earlier than it used to so copies can be dropped off for students with accommodations — and then to mark; there are forms for this and emails about that.

I can’t believe Reading Week is already two weeks ago — but that’s what it’s always like when we come back. I don’t like to say that it’s all downhill from there, but it does always seem as if the term accelerates, even as the work accumulates. And there are just so many moving parts! All the routine business of class meetings continues, including doing the readings, preparing lecture notes or handouts or worksheets or slides, keeping attendance records, and just plain showing up and going through the whole song and dance number — which is the most fun part, but also the most tiring part. From now until after exams, there’s also a constant flow of assignments in and out, and that means getting topics and instructions up in plenty of time; there are tests to prepare — which has to be done earlier than it used to so copies can be dropped off for students with accommodations — and then to mark; there are forms for this and emails about that.

You’d think I’d be used to this, after almost 22 years, and really, I am. Academic work is very cyclical, and this is just, always, a particularly intense part of the cycle. Then suddenly, before it seems possible, classes will be over and there will be “just” exams and papers left, and then everything quiets right down for the summer, when both the work and the pace are different. I’m hanging in there reasonably well in the meantime, though every so often I feel a bit panicked. Clearly, though, one thing that has fallen by the wayside is blogging, partly because I haven’t been getting much interesting reading done outside of class. (I am now happily started on Helen Simonson’s The Summer Before the War, though, so there’s hope!)

One nice thing is that the readings for both classes provided rich fodder for discussion recently. In Pulp Fiction we’ve just wrapped up our time on The Maltese Falcon. For our last session we talked mostly about Sam’s choice between love and justice at the end of the novel. “If they hang you, I’ll always remember you” is hardly a conventionally romantic declaration, but coming from Sam, it seems like a lot! What I find so interesting is that it seems at least possible that he really does love Brigid (though he doesn’t seem quite sure, and neither were we, overall), but it just doesn’t matter to him that much: he’s not even torn over it. We’re so used to stories (and songs, and greeting cards) in which all you need is love, but Sam believes other things matter more (“when a man’s partner dies, he’s supposed to do something about it”), and why not, really? I’m reminded of the scene in The West Wing when Leo’s wife complains that to him, his job (as White House Chief of Staff) is more important than his marriage. “Right now, it is,” he says, and in context that doesn’t seem unreasonable. Sam is a pretty objectionable guy in other ways, so I would never hold him up as exemplary, but it’s refreshing to have someone take the position that “maybe I love you, and maybe you love me” might not be what matters the most. Plus, what a neat segue that sets up for our unit on romance fiction, which starts very soon.

One nice thing is that the readings for both classes provided rich fodder for discussion recently. In Pulp Fiction we’ve just wrapped up our time on The Maltese Falcon. For our last session we talked mostly about Sam’s choice between love and justice at the end of the novel. “If they hang you, I’ll always remember you” is hardly a conventionally romantic declaration, but coming from Sam, it seems like a lot! What I find so interesting is that it seems at least possible that he really does love Brigid (though he doesn’t seem quite sure, and neither were we, overall), but it just doesn’t matter to him that much: he’s not even torn over it. We’re so used to stories (and songs, and greeting cards) in which all you need is love, but Sam believes other things matter more (“when a man’s partner dies, he’s supposed to do something about it”), and why not, really? I’m reminded of the scene in The West Wing when Leo’s wife complains that to him, his job (as White House Chief of Staff) is more important than his marriage. “Right now, it is,” he says, and in context that doesn’t seem unreasonable. Sam is a pretty objectionable guy in other ways, so I would never hold him up as exemplary, but it’s refreshing to have someone take the position that “maybe I love you, and maybe you love me” might not be what matters the most. Plus, what a neat segue that sets up for our unit on romance fiction, which starts very soon.

In 19th-Century Fiction, we’ve just finished Adam Bede. I don’t know why I was worried about how it would go over with the students: compared to The Mill on the Floss or Middlemarch, it has been really easy going! Though it does start slowly, it develops in quite a clear and dramatic way, with main characters who provide strong contrasts to each other in ways that are easy enough to see but still really interesting to examine. I haven’t had any trouble generating discussion, especially once we’d followed Hetty on her journeys in hope and despair and then through her trial, her confession to Dinah, and her [spoiler alert!] dramatic rescue. Though I think the novel has some weaknesses that show Eliot’s inexperience as a novelist (the wooden-headed Adam, for one, and, arguably, the heavy-handed — if delightful — Chapter 17, “In Which the Story Pauses A Little,” for another), it is still astonishingly good, full of wisdom and beauty and humor and pathos. One of the best moments of my whole week — really, of my whole term — was walking back to my office from class on Friday behind a stream of students who were still talking with great animation about Seth, whose happy generosity in the face of [spoiler!] Adam and Dinah’s marriage does, as the students noted, strain credulity. (I know, I know. Nobody reading here cares about spoilers. But you’d be surprised: I remember a graduate seminar being extremely annoyed with their assigned Broadview edition of Adam Bede because its footnotes gave key plot points away in advance.)

On a different note, I actually wrote most of an entirely different post on Wednesday in honor of International Women’s Day. I wanted to pay tribute in some way to the many women who have made a positive difference in my life: the women in my family, my dear friends, the women I work with, the women writers whose books enrich my life in so many ways, the amazing women characters they envisioned who have also served as my inspirations and role models. In the end, though, I decided not to post it, not because I didn’t mean it, but because I couldn’t seem to write it in a way that didn’t sound like vacuous gushing. Maybe that would have been fine, I don’t know, but it seemed shallow to me, when my intentions were just the opposite. Instead, then, you got this rather dull housekeeping post! I really do want to thank and celebrate these wonderful people: I’m just going to find a different way to do so.

On a different note, I actually wrote most of an entirely different post on Wednesday in honor of International Women’s Day. I wanted to pay tribute in some way to the many women who have made a positive difference in my life: the women in my family, my dear friends, the women I work with, the women writers whose books enrich my life in so many ways, the amazing women characters they envisioned who have also served as my inspirations and role models. In the end, though, I decided not to post it, not because I didn’t mean it, but because I couldn’t seem to write it in a way that didn’t sound like vacuous gushing. Maybe that would have been fine, I don’t know, but it seemed shallow to me, when my intentions were just the opposite. Instead, then, you got this rather dull housekeeping post! I really do want to thank and celebrate these wonderful people: I’m just going to find a different way to do so.

This week is Dalhousie’s Reading Week, so I’m enjoying a break from the routine of classes. Last week, though, was also sort of a break, or at least a broken up week, thanks to the massive blizzard that arrived late Sunday night and shut the city down almost completely until Wednesday. And then on Thursday another storm hit — meaning we had three full snow days last week on top of a partial closing the week before. That’s a lot of disruption in a hurry! It was also the first time I can remember Dalhousie announcing a closure the day before, instead of at 6 a.m. the day of (ah, the lovely treat of waking up early to find out if you need to wake up early).

This week is Dalhousie’s Reading Week, so I’m enjoying a break from the routine of classes. Last week, though, was also sort of a break, or at least a broken up week, thanks to the massive blizzard that arrived late Sunday night and shut the city down almost completely until Wednesday. And then on Thursday another storm hit — meaning we had three full snow days last week on top of a partial closing the week before. That’s a lot of disruption in a hurry! It was also the first time I can remember Dalhousie announcing a closure the day before, instead of at 6 a.m. the day of (ah, the lovely treat of waking up early to find out if you need to wake up early). Anyway, one way and another we made our way through the week, and the snow, and now it’s Reading Week. Just because classes aren’t meeting doesn’t mean there isn’t plenty to do, including prepping and grading for them. After the break, we’re starting Adam Bede in 19th-Century Fiction. As this is the first time I’ve assigned it in an undergraduate class, I have no pre-existing materials to draw on, so working some up has been a priority this week. I do know the novel pretty well from having taught it several times in

Anyway, one way and another we made our way through the week, and the snow, and now it’s Reading Week. Just because classes aren’t meeting doesn’t mean there isn’t plenty to do, including prepping and grading for them. After the break, we’re starting Adam Bede in 19th-Century Fiction. As this is the first time I’ve assigned it in an undergraduate class, I have no pre-existing materials to draw on, so working some up has been a priority this week. I do know the novel pretty well from having taught it several times in  Also on my to-do list this week was finishing a review of Lesley Krueger’s Mad Richard for Canadian Notes & Queries, which looks like it will be ready to submit tomorrow, and finalizing my own and my contributors’ pieces for the March issue of Open Letters Monthly. This issue will mark OLM’s 10th anniversary! I didn’t join up as an editor until 2010; I was in time, then, to contribute to our 5th anniversary celebration,

Also on my to-do list this week was finishing a review of Lesley Krueger’s Mad Richard for Canadian Notes & Queries, which looks like it will be ready to submit tomorrow, and finalizing my own and my contributors’ pieces for the March issue of Open Letters Monthly. This issue will mark OLM’s 10th anniversary! I didn’t join up as an editor until 2010; I was in time, then, to contribute to our 5th anniversary celebration,  We’ve started our discussions of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford in 19th-Century Fiction, and like last week’s reading, it has special resonance in these turbulent times, but not because it is a call to action: more because it provides a refuge. This is not to say that it’s “escapist” in the pejorative way that term is often applied, or that it is all (metaphorically) rainbows and lollipops. Actually, rereading the first few chapters I’ve been particularly struck this time by how melancholy they are, despite the wonderful touches of comedy. There are so many deaths — not nearly as many as in Valdez Is Coming, of course, but whereas in that novel most deaths leave little emotional mark, each of the losses in Cranford is deeply felt. There’s little drama (well, Captain Brown’s is pretty startling) but much tenderness. I love the delicacy with which we are brought to understand the depths of Miss Matty’s grief after Mr. Holbrook dies:

We’ve started our discussions of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford in 19th-Century Fiction, and like last week’s reading, it has special resonance in these turbulent times, but not because it is a call to action: more because it provides a refuge. This is not to say that it’s “escapist” in the pejorative way that term is often applied, or that it is all (metaphorically) rainbows and lollipops. Actually, rereading the first few chapters I’ve been particularly struck this time by how melancholy they are, despite the wonderful touches of comedy. There are so many deaths — not nearly as many as in Valdez Is Coming, of course, but whereas in that novel most deaths leave little emotional mark, each of the losses in Cranford is deeply felt. There’s little drama (well, Captain Brown’s is pretty startling) but much tenderness. I love the delicacy with which we are brought to understand the depths of Miss Matty’s grief after Mr. Holbrook dies: Although it is often difficult to concentrate on reading fiction right now, amidst the clamor of current events, it is also the case that current events have their usual uncanny way of making some of the novels I’m reading seem more important than ever.

Although it is often difficult to concentrate on reading fiction right now, amidst the clamor of current events, it is also the case that current events have their usual uncanny way of making some of the novels I’m reading seem more important than ever. The other novel I’ve been working on for class is Valdez Is Coming. It is a pretty different reading experience in almost every way, but it too turns on questions about what’s right and what’s fair, and about when and where to draw the line in the face of an injustice. “Why do you bother?” Valdez is asked about his quest to get restitution for a widow whose fate nobody else cares about because she’s Apache and her dead husband (though shot by Valdez himself) was the victim of their unrepentant racism. “If I tell you what I think,” he replies, “it doesn’t sound right. It’s something I know.” By that time we know too why standing up to the men who mocked him, shot at him, then crucified him when he asked for justice is something he has to do. It’s about not letting them win, yes, but that outcome matters because of who they are, and who he is — and, if we’re on his side, who we want to be, and how we want the world to be. “You get one time, mister, to prove who you are” he tells his antagonist during their final showdown. Valdez (true to his genre) proves who he is through action, including a lot of violence. (I wouldn’t like this novel as much as I do if this violence were treated differently — simply as action, for instance, or drama — but Leonard imbues it with

The other novel I’ve been working on for class is Valdez Is Coming. It is a pretty different reading experience in almost every way, but it too turns on questions about what’s right and what’s fair, and about when and where to draw the line in the face of an injustice. “Why do you bother?” Valdez is asked about his quest to get restitution for a widow whose fate nobody else cares about because she’s Apache and her dead husband (though shot by Valdez himself) was the victim of their unrepentant racism. “If I tell you what I think,” he replies, “it doesn’t sound right. It’s something I know.” By that time we know too why standing up to the men who mocked him, shot at him, then crucified him when he asked for justice is something he has to do. It’s about not letting them win, yes, but that outcome matters because of who they are, and who he is — and, if we’re on his side, who we want to be, and how we want the world to be. “You get one time, mister, to prove who you are” he tells his antagonist during their final showdown. Valdez (true to his genre) proves who he is through action, including a lot of violence. (I wouldn’t like this novel as much as I do if this violence were treated differently — simply as action, for instance, or drama — but Leonard imbues it with  The past couple of weeks have felt pretty hectic to me, mostly because any time you teach a new course, or just new material, you have to build up all its materials from scratch. This term it’s Pulp Fiction that needs, well, everything! Not only do I not have any lecture notes to draw on for most of the readings (but boy, am I looking forward to our weeks on The Maltese Falcon, which I

The past couple of weeks have felt pretty hectic to me, mostly because any time you teach a new course, or just new material, you have to build up all its materials from scratch. This term it’s Pulp Fiction that needs, well, everything! Not only do I not have any lecture notes to draw on for most of the readings (but boy, am I looking forward to our weeks on The Maltese Falcon, which I  In 19th-Century Fiction we are nearly through Bleak House. They seem to be hanging in there! In this class too I have felt myself falling into too much lecturing, but I have been consciously working on balancing that out with some much more open-ended sessions. I feel as if lecturing in a more orderly way can be an important part of our work on a novel as long and complex as Bleak House, where a risk for newcomers to the novel is getting overwhelmed by minutiae: I try in my lecture segments to give them big grids or maps on which they can later place specific characters or incidents as they arise, or rise to prominence. I also try to plant interpretive seeds in the form of questions to be followed up on as they read further. That way, when we do approach topics through discussion, they will already have been thinking about some of them on their own — which usually seems to work!

In 19th-Century Fiction we are nearly through Bleak House. They seem to be hanging in there! In this class too I have felt myself falling into too much lecturing, but I have been consciously working on balancing that out with some much more open-ended sessions. I feel as if lecturing in a more orderly way can be an important part of our work on a novel as long and complex as Bleak House, where a risk for newcomers to the novel is getting overwhelmed by minutiae: I try in my lecture segments to give them big grids or maps on which they can later place specific characters or incidents as they arise, or rise to prominence. I also try to plant interpretive seeds in the form of questions to be followed up on as they read further. That way, when we do approach topics through discussion, they will already have been thinking about some of them on their own — which usually seems to work!

It starts to feel as if I have written a lot of these ‘start of the term’ posts: I’ve used up every variation I can think of for titles! It’s in the nature of academic work to be cyclical, though, and on the bright side, this term I am doing one all-new course, so at least you can look forward to some novelty in my teaching posts!

It starts to feel as if I have written a lot of these ‘start of the term’ posts: I’ve used up every variation I can think of for titles! It’s in the nature of academic work to be cyclical, though, and on the bright side, this term I am doing one all-new course, so at least you can look forward to some novelty in my teaching posts! I’ve sometimes wondered if I should have had a plan, or developed one, in order to give Novel Readings a more definite identity. In the decade since I launched this blog, I’ve seen quite a lot of articles or posts giving advice on blogging, and the key to success is apparently having a mission, or filling a specific niche — along with posting on a regular (and frequent) schedule, and keeping your posts under 1000 words. (Hey, I’m 0 for 3!) I do think the hybrid identity of Novel Readings — which is not really, or at least not just, a book blog, and not really, or not altogether, an academic blog — has probably limited its appeal, because for some bookish people there’s no doubt too much academic stuff here, while for some academics, there’s too much book talk (or, too much book talk that’s not sufficiently academic).

I’ve sometimes wondered if I should have had a plan, or developed one, in order to give Novel Readings a more definite identity. In the decade since I launched this blog, I’ve seen quite a lot of articles or posts giving advice on blogging, and the key to success is apparently having a mission, or filling a specific niche — along with posting on a regular (and frequent) schedule, and keeping your posts under 1000 words. (Hey, I’m 0 for 3!) I do think the hybrid identity of Novel Readings — which is not really, or at least not just, a book blog, and not really, or not altogether, an academic blog — has probably limited its appeal, because for some bookish people there’s no doubt too much academic stuff here, while for some academics, there’s too much book talk (or, too much book talk that’s not sufficiently academic). So: what’s up for this winter term? Something old and something new. I’m doing another iteration of 19th-Century British Fiction (Dickens to Hardy), beginning, this week, with Bleak House, which I haven’t taught (or read) since 2013. I was so sad to read Hilary Mantel identifying Dickens as

So: what’s up for this winter term? Something old and something new. I’m doing another iteration of 19th-Century British Fiction (Dickens to Hardy), beginning, this week, with Bleak House, which I haven’t taught (or read) since 2013. I was so sad to read Hilary Mantel identifying Dickens as  We don’t stay up until midnight on New Year’s Eve anymore. I can’t remember when we gave up on this tradition, exactly. The last New Year’s Eve I specifically remember was 1999-2000: remember the Y2K panic? We didn’t really expect a dramatic catastrophe on the stroke of midnight, but it was hard not to wonder just what would go wrong. I think we rang in the New Year a few times after that, but there came a point at which it was just too obvious that nothing significantly changed with a new date, and also while the children were small, staying up late on purpose when we were already tired all the time didn’t make much sense. This is one way in which I have broken with my upbringing: to this day my intrepid parents and whoever’s celebrating with them stand out on their front porch in Vancouver and listen for the ships in the harbor to tell them when it’s officially midnight, then bang enthusiastically on pots and pans — a ritual I participated in with glee for many years. (To my knowledge, none of our neighbors ever complained.) I don’t think they still have Pêches Flambées for dessert, though: that used to be the showy finale to our elaborate New Year’s Eve dinner.

We don’t stay up until midnight on New Year’s Eve anymore. I can’t remember when we gave up on this tradition, exactly. The last New Year’s Eve I specifically remember was 1999-2000: remember the Y2K panic? We didn’t really expect a dramatic catastrophe on the stroke of midnight, but it was hard not to wonder just what would go wrong. I think we rang in the New Year a few times after that, but there came a point at which it was just too obvious that nothing significantly changed with a new date, and also while the children were small, staying up late on purpose when we were already tired all the time didn’t make much sense. This is one way in which I have broken with my upbringing: to this day my intrepid parents and whoever’s celebrating with them stand out on their front porch in Vancouver and listen for the ships in the harbor to tell them when it’s officially midnight, then bang enthusiastically on pots and pans — a ritual I participated in with glee for many years. (To my knowledge, none of our neighbors ever complained.) I don’t think they still have Pêches Flambées for dessert, though: that used to be the showy finale to our elaborate New Year’s Eve dinner. Anyway, here we are now, writing 2017 instead of 2016 but otherwise puttering along more or less as usual. For me, that means getting things in order for my winter term classes, which begin on Monday — a week later than is typical, which has been a real boon. The campus itself, including the administrative offices, opened up this week, so I’ve been able to get handouts printed and copied and all kinds of other preparatory business done, including a trek across campus to scout out the room where I’ll be teaching ‘Pulp Fiction,’ which is in an unfamiliar building. Will that preemptive action ward off anxiety dreams about getting lost en route? Here’s hoping.

Anyway, here we are now, writing 2017 instead of 2016 but otherwise puttering along more or less as usual. For me, that means getting things in order for my winter term classes, which begin on Monday — a week later than is typical, which has been a real boon. The campus itself, including the administrative offices, opened up this week, so I’ve been able to get handouts printed and copied and all kinds of other preparatory business done, including a trek across campus to scout out the room where I’ll be teaching ‘Pulp Fiction,’ which is in an unfamiliar building. Will that preemptive action ward off anxiety dreams about getting lost en route? Here’s hoping. The very first reading we’re doing, though, is a nifty little short story by Lawrence Block called “How Would You Like It?” I often begin the fiction unit in an introductory class with Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour”: it’s really short, but also full of things to talk about, so it makes a great warm-up exercise. It didn’t really fit ‘Pulp Fiction,’ though, so I hunted through my anthologies looking for something else equally brief that would help us get some key literary terms on the table right away while also (hopefully) catching people’s interest. I found the Block story in an excellent anthology called A Century of Noir; though it actually isn’t exemplary of noir, I liked that it was twisty as well as short, so I thought I’d try it out. One of the topics I always address early on is point of view, along with the different options for narrators; the story will work well for that, and it also provocatively introduces questions about vigilante justice that we will be discussing with both our Westerns and our mystery readings.

The very first reading we’re doing, though, is a nifty little short story by Lawrence Block called “How Would You Like It?” I often begin the fiction unit in an introductory class with Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour”: it’s really short, but also full of things to talk about, so it makes a great warm-up exercise. It didn’t really fit ‘Pulp Fiction,’ though, so I hunted through my anthologies looking for something else equally brief that would help us get some key literary terms on the table right away while also (hopefully) catching people’s interest. I found the Block story in an excellent anthology called A Century of Noir; though it actually isn’t exemplary of noir, I liked that it was twisty as well as short, so I thought I’d try it out. One of the topics I always address early on is point of view, along with the different options for narrators; the story will work well for that, and it also provocatively introduces questions about vigilante justice that we will be discussing with both our Westerns and our mystery readings. My other course this term is 19th-Century British Fiction from Dickens to Hardy. As regular readers will know, I do this class (or its prequel, 19th-Century British Fiction from Austen to Dickens)

My other course this term is 19th-Century British Fiction from Dickens to Hardy. As regular readers will know, I do this class (or its prequel, 19th-Century British Fiction from Austen to Dickens)  In case you were wondering why it has been so quiet here at Novel Readings, I’ve been grading papers industriously, trying to get through them as efficiently as I could consistent with still paying really close attention. I did well at sticking with it, partly thanks to my students, many of whom wrote really good essays! Not only does that speed things up, but it makes the whole process more enjoyable.

In case you were wondering why it has been so quiet here at Novel Readings, I’ve been grading papers industriously, trying to get through them as efficiently as I could consistent with still paying really close attention. I did well at sticking with it, partly thanks to my students, many of whom wrote really good essays! Not only does that speed things up, but it makes the whole process more enjoyable. Before I put this term completely behind me, though, one question lingers after hours spent poring over student writing: what’s up with apostrophes? Actually, I have two questions, because my follow-up to that one is, should I care about apostrophes?

Before I put this term completely behind me, though, one question lingers after hours spent poring over student writing: what’s up with apostrophes? Actually, I have two questions, because my follow-up to that one is, should I care about apostrophes?

We had our last day of classes yesterday. Owing to a very peculiar scheduling plan devised (of course) by a committee, although yesterday was actually a Tuesday, it was designated an “extra Monday” to make up for “losing” a day of Monday classes to Thanksgiving (so much for the concept of a day off — must everything be weighed and measured?). Anyway, that meant two days of Monday classes in a row to bring us to the end of term. As I am not giving final exams in my courses, I now have a lull in immediately pressing teaching-related activities until the final essays come in, the first batch on Friday, the second on Sunday. Then I have to dig in and get through them all, and then do all the final record keeping so that I can compute and submit final grades.

We had our last day of classes yesterday. Owing to a very peculiar scheduling plan devised (of course) by a committee, although yesterday was actually a Tuesday, it was designated an “extra Monday” to make up for “losing” a day of Monday classes to Thanksgiving (so much for the concept of a day off — must everything be weighed and measured?). Anyway, that meant two days of Monday classes in a row to bring us to the end of term. As I am not giving final exams in my courses, I now have a lull in immediately pressing teaching-related activities until the final essays come in, the first batch on Friday, the second on Sunday. Then I have to dig in and get through them all, and then do all the final record keeping so that I can compute and submit final grades. Though the cessation of classes doesn’t mean there’s not anything else to do at work (just for instance, today I put some time in organizing the Brightspace site and readings for one of next term’s courses), I usually take advantage of any break in the schedule at this time of year to get some holiday shopping done, especially for things I want to mail out west to my family. I was especially motivated to get as much done as I could today because so far (unlike my family out west, in a rare reversal!) we have no snow to deal with yet. Sadly, that can’t last, and everything gets harder once the roads and sidewalks are wintry. So once I’d taken care of some business at the office, out I went, and had a pretty nice time puttering around at the mall and in the rather more interesting shops at the

Though the cessation of classes doesn’t mean there’s not anything else to do at work (just for instance, today I put some time in organizing the Brightspace site and readings for one of next term’s courses), I usually take advantage of any break in the schedule at this time of year to get some holiday shopping done, especially for things I want to mail out west to my family. I was especially motivated to get as much done as I could today because so far (unlike my family out west, in a rare reversal!) we have no snow to deal with yet. Sadly, that can’t last, and everything gets harder once the roads and sidewalks are wintry. So once I’d taken care of some business at the office, out I went, and had a pretty nice time puttering around at the mall and in the rather more interesting shops at the  You never know what twists of fate will bring new relevance to the readings you’ve assigned. Teaching A Room of One’s Own soon after the

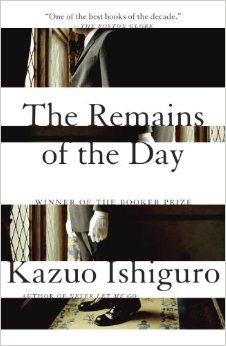

You never know what twists of fate will bring new relevance to the readings you’ve assigned. Teaching A Room of One’s Own soon after the  As much as the specific context of nascent fascism, this indirect approach to it through the internal ruminations of someone well-meaning but ultimately morally compromised, perhaps beyond redemption, seems timely to me. Stevens does not refuse Lord Darlington, for example, when instructed to dismiss two Jewish maids to preserve the “safety and well-being” of his guests. Against Miss Kenton’s passionate rebuke — “if you dismiss my girls tomorrow, it will be wrong, a sin as any sin ever was one” — he sets his own professional standards: “our professional duty is not to our own foibles and sentiments, but to the wishes of our employer.” It might seem a relatively modest act of bigotry to be complicit in, but it’s inexcusable nonetheless, intolerable both in itself (as Miss Kenton rightly notes) and as a concession to the creeping encroachment of worse horrors. Resistance may even mean the most on this personal scale, where you can act before events outsize and overtake you — but in any case the most anyone can do is refuse to cooperate with — or to normalize — what they know to be wrong. From inside Stevens’s head, we feel the appeal of compliance, of pretending that this one thing, or the next thing, doesn’t really matter very much. But against that dangerous ease, as we travel with him to a fuller understanding of what his political passivity has enabled, we can set our own rising horror — at the waste of his life, and at the possibility that

As much as the specific context of nascent fascism, this indirect approach to it through the internal ruminations of someone well-meaning but ultimately morally compromised, perhaps beyond redemption, seems timely to me. Stevens does not refuse Lord Darlington, for example, when instructed to dismiss two Jewish maids to preserve the “safety and well-being” of his guests. Against Miss Kenton’s passionate rebuke — “if you dismiss my girls tomorrow, it will be wrong, a sin as any sin ever was one” — he sets his own professional standards: “our professional duty is not to our own foibles and sentiments, but to the wishes of our employer.” It might seem a relatively modest act of bigotry to be complicit in, but it’s inexcusable nonetheless, intolerable both in itself (as Miss Kenton rightly notes) and as a concession to the creeping encroachment of worse horrors. Resistance may even mean the most on this personal scale, where you can act before events outsize and overtake you — but in any case the most anyone can do is refuse to cooperate with — or to normalize — what they know to be wrong. From inside Stevens’s head, we feel the appeal of compliance, of pretending that this one thing, or the next thing, doesn’t really matter very much. But against that dangerous ease, as we travel with him to a fuller understanding of what his political passivity has enabled, we can set our own rising horror — at the waste of his life, and at the possibility that