I made my way to the end of Tove Ditlevsen’s Copenhagen Trilogy without ever deciding if I was enjoying it or not. Enjoying might be the wrong word in any case: it’s not really a fun or pleasant story, and Ditlevsen herself does not come across as likeable, so what’s to enjoy? The better question is whether I was appreciating or admiring it, or interested in it. I am undecided on these questions as well. And yet her account of her childhood, youth, and “dependency” (meaning addiction) did exert a kind of pull on me, enough that I persisted to the end. One of the rewards, as I mentioned before, is coming across passages that hit hard. Some samples:

I made my way to the end of Tove Ditlevsen’s Copenhagen Trilogy without ever deciding if I was enjoying it or not. Enjoying might be the wrong word in any case: it’s not really a fun or pleasant story, and Ditlevsen herself does not come across as likeable, so what’s to enjoy? The better question is whether I was appreciating or admiring it, or interested in it. I am undecided on these questions as well. And yet her account of her childhood, youth, and “dependency” (meaning addiction) did exert a kind of pull on me, enough that I persisted to the end. One of the rewards, as I mentioned before, is coming across passages that hit hard. Some samples:

I look up at [my mother] and understand many things at once. She is smaller than other adult women, younger than other mothers, and there’s a world outside my street that she fears. And whenever we both fear it together, she will stab me in the back. As we stand there in front of the witch, I also notice that my mother’s hands smell of dish soap. I despise that smell, and as we leave the school again in utter silence, my heart fills with the chaos of anger, sorrow, and compassion that my mother will always awaken in my from that moment on, throughout my life.

Or,

Wherever you turn, you run up against your childhood and hurt yourself because it’s sharp-edged and hard, and stops only when it has torn you completely apart. It seems that everyone has their own and each is totally different. My brother’s childhood is very noisy, for example, while mine is quiet and furtive and watchful. No one likes it and no one has any use for it.

Or this, which is such an uncomfortable kind of yearning, perhaps not completely unfamiliar to anyone who was a precocious girl in a world where that quality was not always welcome:

I desire with all my heart to make contact with a world that seems to consist entirely of sick old men who might keel over at any moment, before I myself have grown old enough to be taken seriously.

Or this, once she has grown into a writer:

I realize more and more that the only thing I’m good for, the only thing that truly captivates me, is forming sentences and word combinations, or writing simple four-line poetry. And in order to do this I have to be able to observe people in a certain way, almost as if I needed to store them in a file somewhere for later use. And to be able to do this I have to be able to read in a certain way too, so I can absorb through all my pores everything I need, if not for now, then for later use. That’s why I can’t interact with too many people . . . and since I’m always forming sentences in my head, I’m often distant and distracted.

As these samples show, there’s a hardness, a flatness, to the narrating voice: as often before, I wondered if that affect was intrinsic to the original or an effect of the translation. There’s also an intensity, and a ruthlessness, towards herself as much as towards others. It is a strong voice, but it does not inspire me to look up any of Ditlevsen’s fiction.

I also finished Miriam Toews’s A Truce That Is Not Peace, which is not really a memoir, I suppose, but I’m not sure what else to call it. It is about her life and about writing and about the death by suicide of her father and her sister—which is to say, it is about the same subjects as most of her other books, which is sort of the point, as it is written in response to a question she cannot clearly answer: “Why do you write?”

I also finished Miriam Toews’s A Truce That Is Not Peace, which is not really a memoir, I suppose, but I’m not sure what else to call it. It is about her life and about writing and about the death by suicide of her father and her sister—which is to say, it is about the same subjects as most of her other books, which is sort of the point, as it is written in response to a question she cannot clearly answer: “Why do you write?”

I did not like this book much as a book, though I admire and sympathize with Toews’s wrestling with questions about how or whether or why to keep returning to these deaths. It’s odd to think that long before I knew that her main subject would become, in a way, my own, I puzzled over my dissatisfaction with her highly autobiographical novel All My Puny Sorrows. One of my thoughts at that time was that she had stuck so closely to the personal that her novel had not offered something more philosophical, something more meaningful. That’s not an obligation for art or artists, of course, but reading AMPS that’s the dimension I felt was missing. In a way, I feel the same about A Truce That Is Not Peace, even as I understand better now how inappropriate it might be, or feel, to move from the personal to the abstract based on one’s own individual experience of this kind of grief or trauma. Certainly that would have meant writing a very different kind of book, and my sense from Truce is that it is not the kind of book Toews would want to write.

What this book communicated to me is a kind of stuckness, a kind of stasis, in her grieving and her thinking about her grieving. I am not complaining that she hasn’t “gotten over” these deaths: that (as I well understand) is not how this works. As she herself is clearly aware, she keeps writing because she isn’t over them, because they aren’t, in that sense, over themselves. Her loss is ongoing. That is a reason, not an explanation, for her writing—if that makes sense as a distinction. It would be nice if writing led to meaning. Sometimes it does, but not always. “Narrative as something dirty, to be avoided,” she says at one point,

I understand this. I understand narrative as failure. Failure is the story, but the story itself is also failure. On its own it will always fail to do the thing it sets out to do—which is to tell the truth.

I sympathize with her grief and anger and frustration, and also with her wish, which I think is implicit in her bothering to write this book at all, that maybe, possibly, hopefully, she can say something truthful if she just keeps at it. I was outraged on her behalf, too, when I read this part:

Is silence the disciplined alternative to writing?

A student of English literature, whose class I recently visited, has suggested that now is the time for me to stand back and listen. I’ve had a “platform” long enough.

But what then—if I stop writing? I don’t want a platform. I am listening. What an awful word! Platform.

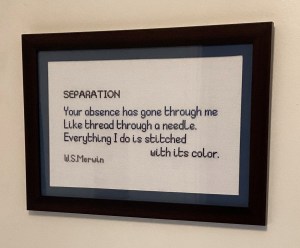

I didn’t much like this particular book. I found it too fragmented, too random; I wanted Toews to actually write the whole book, not to give us what felt (to me) like scraps of it, a draft of it. I understand that its form reflects a refusal to impose order and meaning where she does not find them, but at the same time I am not sure that if anyone but Miriam Toews had written exactly this, it would have found a publisher. But never mind my personal taste, or what I personally go to memoirs about suicide hoping to find (words in the shape of my wound, to paraphrase a poem that still echoes in my mind). We (generally) want to read it because she wrote it and we believe she is worth listening to. Imagine telling the author of Women Talking that she should shut up now.

Here’s something true in it, something that I think Yiyun Li would appreciate for its bluntness, something Denise Riley also talks about. Toews recounts a conversation with a friend whose child died of cancer:

She hated some of the things people said to her afterwards.

I can’t imagine your sorrow. I can’t imagine your pain.

Yeah, you fucking can! You can fucking imagine it. Go ahead and fucking try.

My friend told me she’d never felt more alone and sealed off in her coffin of grief than when people told her, even lovingly, even with tender hugs, that they couldn’t imagine her sadness.

Try! Stay! Stay with me.

“What will happen if I stop writing, I want to ask the student of English literature,” Toews says, right after this anecdote. Maybe the answer to the question that launches this book is here: she writes so that we will stay with her.

There is no good way to say this—when the police arrive, they inevitably preface the bad news with that sentence, as though their presence had not been ominous enough . . .

There is no good way to say this—when the police arrive, they inevitably preface the bad news with that sentence, as though their presence had not been ominous enough . . .

I also remember how angry it made me, in what I now know to call the “acute” phase of grief, to be told “it takes time.” Time for

I also remember how angry it made me, in what I now know to call the “acute” phase of grief, to be told “it takes time.” Time for  Like Riley, whose meditations on grief have been interwoven with my own since almost the beginning, after three years I have nearly stopped writing about it, at least publicly. As I realized long ago, there is a terrible

Like Riley, whose meditations on grief have been interwoven with my own since almost the beginning, after three years I have nearly stopped writing about it, at least publicly. As I realized long ago, there is a terrible

Ruth sighs. It takes a great deal of energy, week after week, pressing her one remaining desire. “Try thinking of doneness as an awful illness then, and bound to be terminal. If you can’t even imagine feeling finished, you must think it’s a pretty terrible state to be in. So it’s about accepting what a person—me—regards as the end of the line. My definition of a fatal disease, which isn’t necessarily yours.”

Ruth sighs. It takes a great deal of energy, week after week, pressing her one remaining desire. “Try thinking of doneness as an awful illness then, and bound to be terminal. If you can’t even imagine feeling finished, you must think it’s a pretty terrible state to be in. So it’s about accepting what a person—me—regards as the end of the line. My definition of a fatal disease, which isn’t necessarily yours.” The others’ counterarguments are also not that robust. “God crops up,” but none of them is religious, or at least doctrinally secure, enough to insist that her plan is wrong or sinful. They are all in varying stages of physical decline, and the one certainty they share is that they will eventually leave the Idyll Inn the same way other residents have, their bodies whisked away as quickly and quietly as possible so as not to discourage the rest. Still, it’s one thing to die and another to kill yourself, or so they try to convince Ruth (“Those people who struggle to be alive. When we are safe and comfortable here—they feel their lives are precious even when they are so very difficult, but you do not feel your life is?” challenges Greta). Ruth is resolute, however, and finally, one by one, they come around. As Sylvia puts it after her own change of heart, “Whatever anyone says—lawyers, doctors, governments, religions, all those nincompoop moral busybodies that float around like weed seeds—we should be in charge of our own selves.”

The others’ counterarguments are also not that robust. “God crops up,” but none of them is religious, or at least doctrinally secure, enough to insist that her plan is wrong or sinful. They are all in varying stages of physical decline, and the one certainty they share is that they will eventually leave the Idyll Inn the same way other residents have, their bodies whisked away as quickly and quietly as possible so as not to discourage the rest. Still, it’s one thing to die and another to kill yourself, or so they try to convince Ruth (“Those people who struggle to be alive. When we are safe and comfortable here—they feel their lives are precious even when they are so very difficult, but you do not feel your life is?” challenges Greta). Ruth is resolute, however, and finally, one by one, they come around. As Sylvia puts it after her own change of heart, “Whatever anyone says—lawyers, doctors, governments, religions, all those nincompoop moral busybodies that float around like weed seeds—we should be in charge of our own selves.” Barfoot simplifies things for her characters by emphasizing Ruth’s clarity of mind and purpose: whether you find her desire to die more or less acceptable as a result is going to depend on your values, but it does, I think, help answer the question “who decides” in her favour. Illnesses like depression affect, perhaps distort, people’s perception of reality: it is harder to defer to their autonomy, then, although perhaps it shouldn’t be, as what makes the most difference to someone’s quality of life is how they experience the world, how they experience life, not what other people insist it is actually like. Of course, we want to believe things will change for them, that they will get better, and most depressed people will. What does that mean about their right to say, as Ruth does, “my time, my place, my way,” or our right to intervene? One of the most insightful discussions I’ve heard about suicide since Owen’s death is

Barfoot simplifies things for her characters by emphasizing Ruth’s clarity of mind and purpose: whether you find her desire to die more or less acceptable as a result is going to depend on your values, but it does, I think, help answer the question “who decides” in her favour. Illnesses like depression affect, perhaps distort, people’s perception of reality: it is harder to defer to their autonomy, then, although perhaps it shouldn’t be, as what makes the most difference to someone’s quality of life is how they experience the world, how they experience life, not what other people insist it is actually like. Of course, we want to believe things will change for them, that they will get better, and most depressed people will. What does that mean about their right to say, as Ruth does, “my time, my place, my way,” or our right to intervene? One of the most insightful discussions I’ve heard about suicide since Owen’s death is

Help me say what can’t be said, you ask me.

Help me say what can’t be said, you ask me. “It must be said,” Irina says to Concita, “that losing a child is the touchstone of grief, the gold standard of pain. The benchmark.” This is uncomfortable territory: it doesn’t seem right to weigh one grief against another. “Never would I compare my state with that of, say, a widow’s,” Denise Riley says in Time Lived, Without Its Flow”; “never would I lay claim to ‘the worst grief of all.'” Yet Riley, whose adult son died suddenly of a previously undetected heart defect, goes on to make other comparisons:

“It must be said,” Irina says to Concita, “that losing a child is the touchstone of grief, the gold standard of pain. The benchmark.” This is uncomfortable territory: it doesn’t seem right to weigh one grief against another. “Never would I compare my state with that of, say, a widow’s,” Denise Riley says in Time Lived, Without Its Flow”; “never would I lay claim to ‘the worst grief of all.'” Yet Riley, whose adult son died suddenly of a previously undetected heart defect, goes on to make other comparisons: It has been quiet around here. I’m not really sure why that is. I’ve been busy at work, but that has never stopped me before. When this term began, I intended to make posting about my teaching routine again. When I kept that up, in the old days, it didn’t matter if I felt I had something in particular to say when I started: eventually I would discover what I had to say, because (as I’ve been trying to convince my first-year students) that’s how writing works. My reading hasn’t been going very well, but I used to write about it anyway.

It has been quiet around here. I’m not really sure why that is. I’ve been busy at work, but that has never stopped me before. When this term began, I intended to make posting about my teaching routine again. When I kept that up, in the old days, it didn’t matter if I felt I had something in particular to say when I started: eventually I would discover what I had to say, because (as I’ve been trying to convince my first-year students) that’s how writing works. My reading hasn’t been going very well, but I used to write about it anyway.

“So far the votes are two Asperger’s, one probably OCD, and one possible ADHD,” he tells Martin, a neuroscientist friend of Alyssa’s to whom he eventually turns for help. “Most of the common meds are pretty normalized,” Martin comments, but when Theo insists that he wants “some treatment short of drugs,” Martin proposes that Robbie enter his ongoing trial of a therapy called

“So far the votes are two Asperger’s, one probably OCD, and one possible ADHD,” he tells Martin, a neuroscientist friend of Alyssa’s to whom he eventually turns for help. “Most of the common meds are pretty normalized,” Martin comments, but when Theo insists that he wants “some treatment short of drugs,” Martin proposes that Robbie enter his ongoing trial of a therapy called  Theo’s tense, beautiful, heartbreaking account of his life with Robin is intercut with their “visits” to other planets: part of Theo’s work is running simulations of what kind of life might emerge under wildly varying conditions which he and Robbie “explore” with exhilarating curiosity and awe. These sections are weird and wonderful, visions of possible worlds completely unlike our own and yet always imagined as possible points of connection. On the planet Pelagos, for instance,

Theo’s tense, beautiful, heartbreaking account of his life with Robin is intercut with their “visits” to other planets: part of Theo’s work is running simulations of what kind of life might emerge under wildly varying conditions which he and Robbie “explore” with exhilarating curiosity and awe. These sections are weird and wonderful, visions of possible worlds completely unlike our own and yet always imagined as possible points of connection. On the planet Pelagos, for instance, I was initially drawn to Bewilderment because of its description as the story of a father and his “rare and troubled boy.” I had a son like that, and while his specific passions and hardships were not the same as Robbie’s, Powers captures a lot of what it was like to try and to fail to know what was right for someone whose gifts and whose difficulties were equally extraordinary, excessive, sometimes exhausting, especially but not only for him. I too liked my son “otherworldly”; his ingenuousness was so precious, even as it made him, sometimes, so vulnerable. “His pronouncements were off-the-wall mysteries to everyone except me,” Theo says of Robin;

I was initially drawn to Bewilderment because of its description as the story of a father and his “rare and troubled boy.” I had a son like that, and while his specific passions and hardships were not the same as Robbie’s, Powers captures a lot of what it was like to try and to fail to know what was right for someone whose gifts and whose difficulties were equally extraordinary, excessive, sometimes exhausting, especially but not only for him. I too liked my son “otherworldly”; his ingenuousness was so precious, even as it made him, sometimes, so vulnerable. “His pronouncements were off-the-wall mysteries to everyone except me,” Theo says of Robin;