January was an OK reading month overall—not great, but with some highlights.

I started with two of the books I picked up at Bookmark’s Boxing Day sale: Vincent van Gogh’s For Life and For Art, which is one of those sweet little Penguin Archive editions. It fell a bit flat for me. I chose it because I was curious to get some insights into van Gogh’s creative process, and there are certainly some interesting passages. One example:

The work is going fairly well. I’m struggling with a canvas I started a few days before my illness—a reaper. The study is all yellow, extremely thickly painted, but the subject was beautiful and simple. For I see in this reaper—a vague figure toiling for all he’s worth in the midst of the heat to finish his task—I see in him the image of death, in the sense that humanity might be the wheat he is reaping. So it is, if you like, the opposite of the sower which I tried to do before. But there is no sadness in this death, this one takes place in broad daylight with a sun flooding everything with a light of pure gold.

In other places he talks quite a bit about how he uses paint, something to which (to be honest) I have paid a lot more attention since I started doing jigsaw puzzles, which often require minute scrutiny to colour and texture. Much of the book, though, which is all letters (mostly to his brother Theo) are about pretty mundane stuff, like art supplies. Not that there’s anything wrong with that! But van Gogh’s paintings are so strange and extraordinary that I expected the same here.

Then I read Kathy Page’s In This Faulty Machine, which is a memoir about her diagnosis with Parkinson’s disease. Again it fell a bit flat, which feels like a terrible thing to say about a book that is so personal and also recounts such a profoundly difficult experience. In this case too there are passages that made me pause with appreciation, such as this one about find words for what she is going through:

In times of great loss, meaning flows back into apt but outworn expressions and they seem true again. So it’s possible, even likely, that as my difficulties become more acute, I will find that plain ordinary words; roughly fitting, well-used phrases; and even squirm-inducing metaphors are good enough—perhaps at times better—than nuanced and original phrasings that draw attention to themselves. After all, sweating, terrified, I’m unlikely to waste my time gazing at the approaching forest fire while I struggle for alternatives to ‘wall of flames’ or choose an original way to convey the ghastly, devouring sound it makes. Since I want to communicate, somehow, anyhow, whatever it takes, I may perhaps be glad of whatever first comes to mind.

Perhaps. Maybe. Meanwhile, I have good reasons for being very passionate about words, and I am not on any kind of journey.

A lot of this book is about Parkinson’s – the symptoms, the treatments, the challenges. Near the end Page says that she wants “my account of these five years to be of use to others,” and I think that intention may be why there’s a fair amount in it that is quite literal, not a how-to guide or instruction manual but, in spirit, a bit of an ‘introduction to.’ Page is a good writer: I was interested in the book in the first place because I really admired her novel Dear Evelyn, which I reviewed for Quill & Quire when it came out. And This Faulty Machine is fine, especially when she meditates on illness and its effects on self and identity and creativity. I’ve just read some memoirs recently that really lit me up—I’m thinking of both Sarah Moss’s My Good Bright Wolfand Claire Cameron’s How to Survive a Bear Attack—and I just did not feel the same about this one.

I bought one more book at that sale, Maria Reva’s Endling, which I had been excited about reading ever since hearing her interviewed about it on Bookends. I am sorry to say that at this point this one is a DNF for me, though I hope I will try it again some day. The metafictional turn it took (which I knew was coming, so I did go into this with my eyes open) quenched my already faltering engagement. YMMV.

I followed up on a recommendation on Bluesky and read Joseph O’Connor’s My Father’s House. This one was high on the “readability” scale and also felt unhappily topical, as all books about resisting fascism do at this point. I didn’t feel compelled to read it at all closely, though, and in fact at times I skimmed along because I was more driven by curiosity about what would happen than I was taking pleasure in its language. It has already gone back to the library, so I can’t quote from it.

A friend leant me Antonia White’s Frost in May, which I have had on my mental TBR for probably decades, given its status as the first-ever Virago Classic. I quite enjoyed this one (although again it has been returned, so I can’t quote from it—such are the hazards of not blogging each book properly as I finish reading it!). My friend commented, and I agree, that it is perhaps a bit too detailed about the religious aspects, but Nanda is a very appealing protagonist to follow along with during her ‘coming of age,’ and I liked White’s prose a lot.

Ned Beauman’s Venomous Lumpsucker would have been a DNF if I hadn’t been reading it for my book club, and as it was I petulantly turned every page after about the first 150, rather than diligently reading it all. As with Endling I have mostly myself to blame for getting into this one: we read Ian McEwan’s What We Can Know last, and decided we’d like something with some similar themes (e.g. environmentalism, climate change, investigation) but with a more plotty plot, a bit more excitement. Venomous Lumpsucker was one of the books I put on a menu of options and it sure sounded like it would be all kinds of madcap fun. Nope. For me, anyway, Beauman just spent waaaaay too much time filling in all the details required by his concept. It dragged soooooo much. I’ll be quite curious to know how my book club friends got on with it.

I finished Volume 3 of Woolf’s diaries: this is a case in which I have too many passages flagged to do this reading experience justice in this quick recap. She’s working on The Waves for much of the last part of this volume and it is really fascinating watching her think it through. One thing that really comes through in the diaries is that she was never content to sit in one place as a novelist: she was always asking what else she could do, or how better she could create fiction that reflected the ideas and experiences she wanted to convey. I have started Volume 4 and fully intend to do better at posting about it regularly (she says boldly).

Finally, I had heard good things about Virginia Evans’s The Correspondent so I grabbed it up when I happened upon it on the ‘rapid reads’ shelf at the library. It is also very readable, and also smart and subtle and touching. Its epistolary approach made me think of Jane Gardam’s Queen of the Tambourine, although it has been so long since I read that one that I don’t know how much beyond their form they have in common. I pulled the Gardam off myself and added it to my actual TBR pile: I enjoyed it a lot when I read it back in (checks blog archive) 2011. 2011! That’s a long time ago.

And now it’s February, a new month, a short month, a (probably) pretty busy month. One reason I haven’t been posting is that I’ve been so tired after the work stuff is done: it has been a dreary time at work administratively, with budget cuts and internecine wrangling and lots of doom and gloom ‘what if’ conversations, fiscal as well as curricular. Honestly I’m surprised I even read this much (which isn’t that much, by some standards) in January. I’m enjoying my actual classes, though, and I hope the students are too—although if the current forecast holds we may have our third Monday in a row cancelled for snow. Did I mention I’ve been tired?! Still, we are working through the final part of The Mill on the Floss in the George Eliot seminar and that, of course, is genuinely great reading, and Friday’s class in the Brit Lit survey was on “Goblin Market”—what larks! (We start Great Expectations soon, too!)

This post is a re-done version of my previous January 2026 update to correct a number of odd things that happened when I tried to use the latest incarnation of the ‘classic’ editor. Time to learn how to use blocks, I guess–which is what I did here.

Will I survive a bear attack? I’d been asking the wrong question. Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love.

Will I survive a bear attack? I’d been asking the wrong question. Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love. We were more wary about bears when we camped at

We were more wary about bears when we camped at  The bear’s story becomes the third strand in the narrative Cameron weaves, which combines her personal story, the story she puts together (including various testimonies and evidence) about Carola and Ray’s horrific final day, and sections from the point of view of the bear that attempt to portray him as a character in his own right – personality, curiosity, hunger, all as far as possible conveyed as aspects of what we might call bearishness

The bear’s story becomes the third strand in the narrative Cameron weaves, which combines her personal story, the story she puts together (including various testimonies and evidence) about Carola and Ray’s horrific final day, and sections from the point of view of the bear that attempt to portray him as a character in his own right – personality, curiosity, hunger, all as far as possible conveyed as aspects of what we might call bearishness

They belonged here. Of course. It was obvious. They belonged here and they should be here. Why not? Why on earth not? Why should she and Polly leave the Point to a land trust rather than to the people who had loved it the longest? Her heart pounded. It had taken her her whole life to see it, but now that she did, nothing could be as clear. The simple truths are always hidden in plain sight, only veiled by the complications of the human mind.

They belonged here. Of course. It was obvious. They belonged here and they should be here. Why not? Why on earth not? Why should she and Polly leave the Point to a land trust rather than to the people who had loved it the longest? Her heart pounded. It had taken her her whole life to see it, but now that she did, nothing could be as clear. The simple truths are always hidden in plain sight, only veiled by the complications of the human mind. Agnes, in contrast, has to get out of her own way, to stop guarding her secrets and make space in her life for love and forgiveness. This means reckoning with a traumatic incident from her past, which we learn about through the device of a long series of letters she wrote to her dead sister, which she eventually decides to share with the novel’s third protagonist, Maud Silver, an ambitious young editor eager to convince Agnes to write a full and frank memoir.

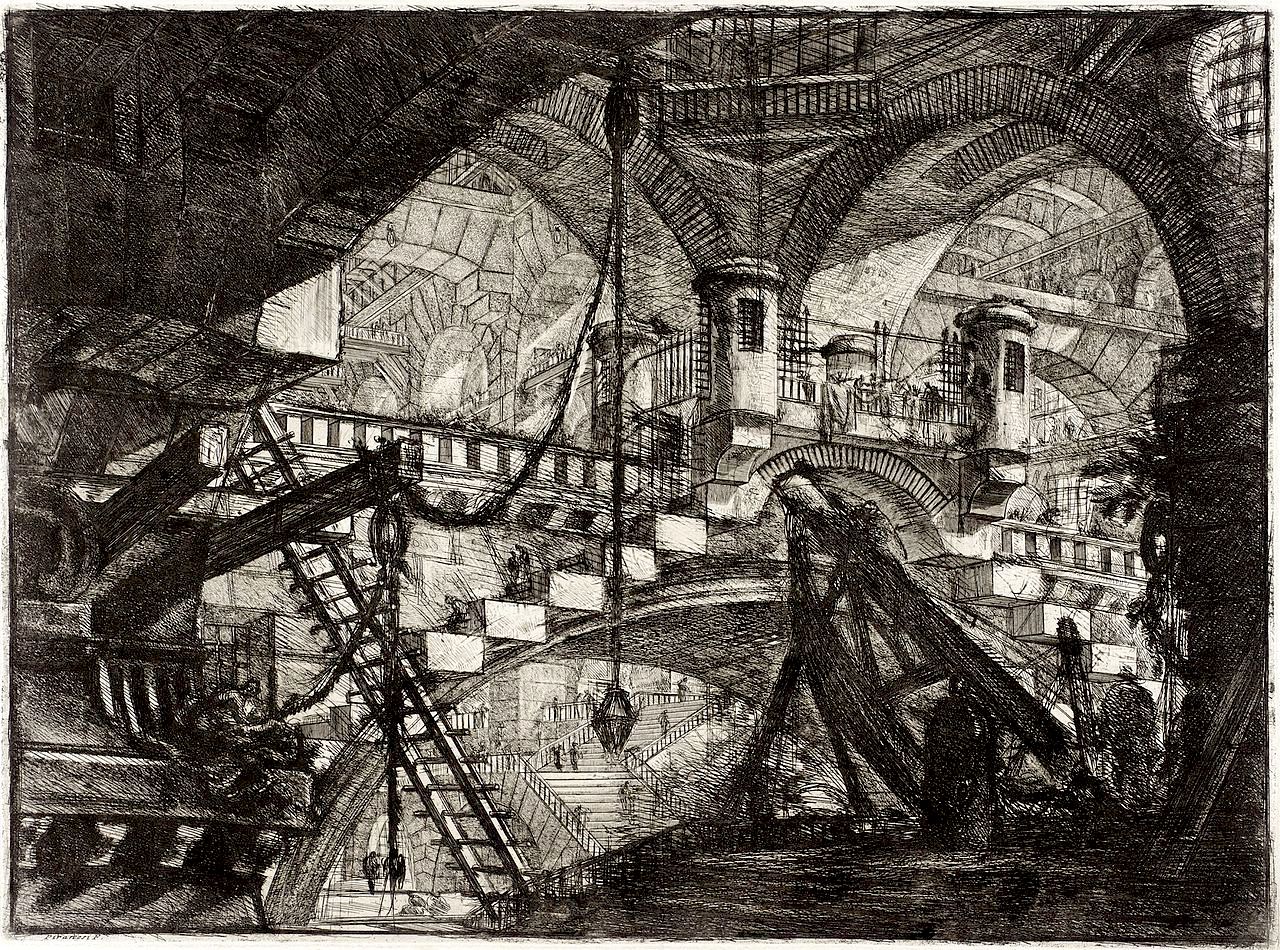

Agnes, in contrast, has to get out of her own way, to stop guarding her secrets and make space in her life for love and forgiveness. This means reckoning with a traumatic incident from her past, which we learn about through the device of a long series of letters she wrote to her dead sister, which she eventually decides to share with the novel’s third protagonist, Maud Silver, an ambitious young editor eager to convince Agnes to write a full and frank memoir. In my mind are all the tides, their seasons, their ebbs and their flows. In my mind are all the halls, the endless procession of them, the intricate pathways. When this world becomes too much for me, when I grow tired of the noise and the dirt and the people, I close my eyes and I name a particular vestibule to myself; then I name a hall. I imagine I am walking the path from the vestibule to the hall. I note with precision the doors I must pass through, the rights and lefts that I must take, the statues on the walls that I must pass.

In my mind are all the tides, their seasons, their ebbs and their flows. In my mind are all the halls, the endless procession of them, the intricate pathways. When this world becomes too much for me, when I grow tired of the noise and the dirt and the people, I close my eyes and I name a particular vestibule to myself; then I name a hall. I imagine I am walking the path from the vestibule to the hall. I note with precision the doors I must pass through, the rights and lefts that I must take, the statues on the walls that I must pass. The story of who he is and what he’s doing in this place is the novel’s central plot, and it has elements of an actual mystery, even a thriller, with clues and an investigation and a climactic face-off with a villainous antagonist. In a way it is even a horror story, or at any rate things about it are horrible. The oddity of Piranesi, though, is how beautiful Piranesi’s weird world is and how lovingly he studies and tends to it. It isn’t our world but it has things we are familiar with, including tides and sea birds and seasons, all of which are vividly evoked. Although Piranesi is essentially (we learn) a captive in this place, it’s not a story of suffering. He feels taken care of; in his isolation, he has created meaning through rituals and through relationships that are real and valuable to him. When the truth is revealed and he has to choose which world to live in, it’s not obvious where he will really be better off. Or, at any rate, the right choice may be obvious but it clearly comes with costs, with losses.

The story of who he is and what he’s doing in this place is the novel’s central plot, and it has elements of an actual mystery, even a thriller, with clues and an investigation and a climactic face-off with a villainous antagonist. In a way it is even a horror story, or at any rate things about it are horrible. The oddity of Piranesi, though, is how beautiful Piranesi’s weird world is and how lovingly he studies and tends to it. It isn’t our world but it has things we are familiar with, including tides and sea birds and seasons, all of which are vividly evoked. Although Piranesi is essentially (we learn) a captive in this place, it’s not a story of suffering. He feels taken care of; in his isolation, he has created meaning through rituals and through relationships that are real and valuable to him. When the truth is revealed and he has to choose which world to live in, it’s not obvious where he will really be better off. Or, at any rate, the right choice may be obvious but it clearly comes with costs, with losses. Happily, other people have written smart things about it, including

Happily, other people have written smart things about it, including  They are worth more to us than the empty human shells we have taken them for; they were children who cried for their mothers, they were young women who fell in love; they endured childbirth, the death of parents; they laughed, and they celebrated Christmas. They argued with their siblings, they wept, they dreamed, they hurt, they enjoyed small triumphs.

They are worth more to us than the empty human shells we have taken them for; they were children who cried for their mothers, they were young women who fell in love; they endured childbirth, the death of parents; they laughed, and they celebrated Christmas. They argued with their siblings, they wept, they dreamed, they hurt, they enjoyed small triumphs. She is also committed to undoing the sensationalism around her subjects’ lives and deaths: I think that’s another explanation for the way she writes the book. She avoids all the obvious kinds of narrative manipulation: she creates no suspense, she does not set a foreboding tone, use foreshadowing, or create melodramatic scenarios or dramatic climaxes. This is one way The Five differs from Dean Jobb’s The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: although I did not find his treatment of this murderer’s victims exploitive, Jobb does enjoy dramatic irony and foreshadowing, and overall he tells a more melodramatic and grisly tale. He also, obviously, focuses on the killer, whereas Rubenhold refuses to give Jack the Ripper any more attention than is absolutely necessary. (For instance, there is no speculation at all in The Five about who he was.)

She is also committed to undoing the sensationalism around her subjects’ lives and deaths: I think that’s another explanation for the way she writes the book. She avoids all the obvious kinds of narrative manipulation: she creates no suspense, she does not set a foreboding tone, use foreshadowing, or create melodramatic scenarios or dramatic climaxes. This is one way The Five differs from Dean Jobb’s The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: although I did not find his treatment of this murderer’s victims exploitive, Jobb does enjoy dramatic irony and foreshadowing, and overall he tells a more melodramatic and grisly tale. He also, obviously, focuses on the killer, whereas Rubenhold refuses to give Jack the Ripper any more attention than is absolutely necessary. (For instance, there is no speculation at all in The Five about who he was.) And no matter how they came to be “sleeping rough,” they didn’t invite or deserve their horrendous deaths. The idea that any version of their life stories should mitigate our distress at the violence done to them—that in any way their murders open them up to that kind of judgment of their characters—is precisely what Rubenhold is crusading against. The epigraph for her conclusion comes from the judge at the trial of the so-called “Suffolk Strangler” in 2008: “You may view with some distaste the lifestyles of those involved,” he says, but “no-one is entitled to do these women any harm, let alone kill them.” Since the first inquests into their deaths, Rubenhold shows, her five have been dismissed as “only prostitutes,” perpetuating the familiar Madonna / whore dichotomy that “suggests there is an acceptable standard of female behavior, and those who deviate from it are fit to be punished.” She rightly points out how persistent this view is, to this day:

And no matter how they came to be “sleeping rough,” they didn’t invite or deserve their horrendous deaths. The idea that any version of their life stories should mitigate our distress at the violence done to them—that in any way their murders open them up to that kind of judgment of their characters—is precisely what Rubenhold is crusading against. The epigraph for her conclusion comes from the judge at the trial of the so-called “Suffolk Strangler” in 2008: “You may view with some distaste the lifestyles of those involved,” he says, but “no-one is entitled to do these women any harm, let alone kill them.” Since the first inquests into their deaths, Rubenhold shows, her five have been dismissed as “only prostitutes,” perpetuating the familiar Madonna / whore dichotomy that “suggests there is an acceptable standard of female behavior, and those who deviate from it are fit to be punished.” She rightly points out how persistent this view is, to this day:

With that in mind, I asked the Twitter ‘hivemind’ for examples of what people consider the best books for or about teaching creative writing. I got a lot of suggestions: Charles Baxter’s Burning Down the House; Nancy Kress’s Beginnings, Middles, and Ends; Sarah Painter’s Stop Worrying, Start Writing; Robert Boswell’s The Half-Known World; Graywolf Press’s The Art Of series; Tin House’s Between the Covers podcast; Ursula LeGuin’s Steering the Craft, Janet Burroway’s Writing Fiction.* One that got a few strong endorsements was Margot Livesey’s The Hidden Machinery. It sounded appealing, so it’s the one I decided to read first (and, I now think, maybe last).

With that in mind, I asked the Twitter ‘hivemind’ for examples of what people consider the best books for or about teaching creative writing. I got a lot of suggestions: Charles Baxter’s Burning Down the House; Nancy Kress’s Beginnings, Middles, and Ends; Sarah Painter’s Stop Worrying, Start Writing; Robert Boswell’s The Half-Known World; Graywolf Press’s The Art Of series; Tin House’s Between the Covers podcast; Ursula LeGuin’s Steering the Craft, Janet Burroway’s Writing Fiction.* One that got a few strong endorsements was Margot Livesey’s The Hidden Machinery. It sounded appealing, so it’s the one I decided to read first (and, I now think, maybe last). The Hidden Machinery is a perfectly fine book about how some really good novels are written. It is mostly close reading. There are zero revelations in it for anyone who has read, say A Passage to India or Persuasion or Madame Bovary attentively with an eye to things like point of view or narrative form or metaphorical patterns or character development. Livesey does a good job walking us through her examples; she is an observant and insightful reader. In her discussion about her own fiction, she explains clearly what she thinks she learned, where she thinks she succeeded or failed, as a result, at least in part, of the attention she learned to pay to other writers. These sections are interesting, but they are not really transferable “lessons”, because each of her novels (like every novel) is unique. There is absolutely no specific advice about how to be as good as her exemplary writers are–and how could there be? There is, near the end, a list of “rules” (derived, a bit unexpectedly for a novelist, from her study of Shakespeare) and it is as useful and as useless as every such list I’ve ever seen: “don’t keep back the good stuff”; “negotiate your own standard of plausibility”; “don’t overexplain”; “write better sentences.” “Don’t overexplain” would probably rule out a novel like Byatt’s

The Hidden Machinery is a perfectly fine book about how some really good novels are written. It is mostly close reading. There are zero revelations in it for anyone who has read, say A Passage to India or Persuasion or Madame Bovary attentively with an eye to things like point of view or narrative form or metaphorical patterns or character development. Livesey does a good job walking us through her examples; she is an observant and insightful reader. In her discussion about her own fiction, she explains clearly what she thinks she learned, where she thinks she succeeded or failed, as a result, at least in part, of the attention she learned to pay to other writers. These sections are interesting, but they are not really transferable “lessons”, because each of her novels (like every novel) is unique. There is absolutely no specific advice about how to be as good as her exemplary writers are–and how could there be? There is, near the end, a list of “rules” (derived, a bit unexpectedly for a novelist, from her study of Shakespeare) and it is as useful and as useless as every such list I’ve ever seen: “don’t keep back the good stuff”; “negotiate your own standard of plausibility”; “don’t overexplain”; “write better sentences.” “Don’t overexplain” would probably rule out a novel like Byatt’s  I was looking for something in Livesey’s book that would be an “aha” moment for me about creative writing as something that can be taught. There was such a moment, but it didn’t exactly confirm for me that what’s most important is classes or programs dedicated to the how-to side. Many, many times I have sat at the English Department’s table at the “academic program fair” held yearly to showcase and recruit students to our various majors and honours program. Year after year, since we started offering creative writing courses, the vast majority of student inquiries are about them, not about our “standard” literature courses. But in those literature courses we do exactly what Livesey does in The Hidden Machinery,** and if you do a majors or honours degree in our department you will perforce study examples across a range of periods and genres–not just the contemporary ones or the ones students already know they are interested in, but the ones they don’t know they are going to love, the literary “unknown unknowns.” Many, many times I have asked prospective creative writing students what other writers, what literary periods or forms, they are most interested in, and many, many times they have had no answer: they just “like to write.”

I was looking for something in Livesey’s book that would be an “aha” moment for me about creative writing as something that can be taught. There was such a moment, but it didn’t exactly confirm for me that what’s most important is classes or programs dedicated to the how-to side. Many, many times I have sat at the English Department’s table at the “academic program fair” held yearly to showcase and recruit students to our various majors and honours program. Year after year, since we started offering creative writing courses, the vast majority of student inquiries are about them, not about our “standard” literature courses. But in those literature courses we do exactly what Livesey does in The Hidden Machinery,** and if you do a majors or honours degree in our department you will perforce study examples across a range of periods and genres–not just the contemporary ones or the ones students already know they are interested in, but the ones they don’t know they are going to love, the literary “unknown unknowns.” Many, many times I have asked prospective creative writing students what other writers, what literary periods or forms, they are most interested in, and many, many times they have had no answer: they just “like to write.” I love that they like to write! But I have always thought (and sometimes said, as tactfully as I could) that to write well you really, really need to read widely. If Livesey’s typical at all–and in this respect I do think she is–that’s what creative writing teachers think too. I’m just still left wondering why an English degree isn’t, then, the right or even best way for these students to proceed, and why they don’t know that. The counter-argument probably turns as much on time, encouragement, and mentorship as on the belief that you can actually teach someone to write something worth reading or even, one day, something that is itself worth studying as an example. Those are definitely good things for aspiring writers to have, even if they are neither necessary nor sufficient factors for producing good, much less great, writers.

I love that they like to write! But I have always thought (and sometimes said, as tactfully as I could) that to write well you really, really need to read widely. If Livesey’s typical at all–and in this respect I do think she is–that’s what creative writing teachers think too. I’m just still left wondering why an English degree isn’t, then, the right or even best way for these students to proceed, and why they don’t know that. The counter-argument probably turns as much on time, encouragement, and mentorship as on the belief that you can actually teach someone to write something worth reading or even, one day, something that is itself worth studying as an example. Those are definitely good things for aspiring writers to have, even if they are neither necessary nor sufficient factors for producing good, much less great, writers.

We pick up again about a decade later and much has changed. Most importantly, Aren has left his adopted family and is living a bit of a rough life in Halifax. Distressed and frustrated, both on his behalf and her own, Kay comes up with a plan to take him “home” to Pulo Anna. Once more we find ourselves on board ship and traveling across the seas. Although the next part of the book is as carefully and thoughtfully crafted as the first part, as I made my way through it, and even more so at the end of the novel, I found myself preoccupied with what Endicott had left out by not addressing the intervening years: a lot was missing, I thought, that would have illuminated both the action and, more importantly, the meaning, of the novel’s resolution.

We pick up again about a decade later and much has changed. Most importantly, Aren has left his adopted family and is living a bit of a rough life in Halifax. Distressed and frustrated, both on his behalf and her own, Kay comes up with a plan to take him “home” to Pulo Anna. Once more we find ourselves on board ship and traveling across the seas. Although the next part of the book is as carefully and thoughtfully crafted as the first part, as I made my way through it, and even more so at the end of the novel, I found myself preoccupied with what Endicott had left out by not addressing the intervening years: a lot was missing, I thought, that would have illuminated both the action and, more importantly, the meaning, of the novel’s resolution. It is hard to know how to begin the 2020-21 iteration of

It is hard to know how to begin the 2020-21 iteration of  So how is it going? One of the oddest things about it, to be honest, is that I really have no idea. The whole past week felt like a massive anti-climax: after months of work, trying to re-train myself and take on board an overwhelming amount of information about “best practices” for online course design and student engagement and teacher presence, after taking a 9-week online course myself to learn about how to do this, after countless hours revising my course outlines and schedules and learning new tools and building my actual Brightspace course sites … all with September 8 as the looming deadline for when the students would “arrive” and the whole experiment would really begin … After all of this, there was no one moment when we were back in class, no online equivalent to that exhilarating and terrifying first face to face session. Instead, because this is how asynchronous online teaching works, students just gradually and on their own timeline started checking in and making their first contributions, while I watched and waited and wondered and tried not to pounce too fast whenever a new notification appeared.

So how is it going? One of the oddest things about it, to be honest, is that I really have no idea. The whole past week felt like a massive anti-climax: after months of work, trying to re-train myself and take on board an overwhelming amount of information about “best practices” for online course design and student engagement and teacher presence, after taking a 9-week online course myself to learn about how to do this, after countless hours revising my course outlines and schedules and learning new tools and building my actual Brightspace course sites … all with September 8 as the looming deadline for when the students would “arrive” and the whole experiment would really begin … After all of this, there was no one moment when we were back in class, no online equivalent to that exhilarating and terrifying first face to face session. Instead, because this is how asynchronous online teaching works, students just gradually and on their own timeline started checking in and making their first contributions, while I watched and waited and wondered and tried not to pounce too fast whenever a new notification appeared.

I’m also genuinely pleased about the contributions that have come in, especially, in both courses, the introductions students have been posting on our “getting to know each other” discussion boards. As I said to them, our first crucial task is to begin building the class into a community, and it has been lovely to see them embrace that goal by telling us a little bit about themselves and then (best of all) responding with great friendliness to each other. I don’t usually solicit individual introductions in all of my F2F classes, only in the smaller seminars, so actually I know more about these groups than I think I ever have this early in the term. While a lot of what I read and practiced this summer was about how to make myself present to my students as a real, if virtual, person, this exercise has been great for making them present to me, not just “students” in the abstract but two really varied and interesting groups of people who bring different perspectives, interests, and needs to our collective enterprise.

I’m also genuinely pleased about the contributions that have come in, especially, in both courses, the introductions students have been posting on our “getting to know each other” discussion boards. As I said to them, our first crucial task is to begin building the class into a community, and it has been lovely to see them embrace that goal by telling us a little bit about themselves and then (best of all) responding with great friendliness to each other. I don’t usually solicit individual introductions in all of my F2F classes, only in the smaller seminars, so actually I know more about these groups than I think I ever have this early in the term. While a lot of what I read and practiced this summer was about how to make myself present to my students as a real, if virtual, person, this exercise has been great for making them present to me, not just “students” in the abstract but two really varied and interesting groups of people who bring different perspectives, interests, and needs to our collective enterprise. Still, I find the spread of the experience out over all hours of the day and all the days of the week disorienting, destabilizing, uncomfortable. Usually my weekly schedule involves regular build-ups to each class meeting: preparing notes and materials and ideas and plans, doing the reading, summoning the energy. Then there’s the live session, which in the moment absorbs all my concentration. When it’s over, I’m drained, even if (especially if!) there has been a really good, lively discussion: being in the moment for that kind of exchange is unlike anything else I do in terms of how focused but also flexible, how attentive to others but also on-task I need to be. I love it, and I really miss it already. I know we can have engaged and intellectually serious exchanges in our online format, but they won’t have the same rhythm, or perhaps any rhythm at all, who knows. Not having to be up and dressed and out the door early in the morning (or ever!) is some compensation, and I expect I will find more of a routine as we settle into the term, but (and I expect I’m going to be saying things like this a lot this term, so sorry for the repetition) it’s a strange new way of being a professor.

Still, I find the spread of the experience out over all hours of the day and all the days of the week disorienting, destabilizing, uncomfortable. Usually my weekly schedule involves regular build-ups to each class meeting: preparing notes and materials and ideas and plans, doing the reading, summoning the energy. Then there’s the live session, which in the moment absorbs all my concentration. When it’s over, I’m drained, even if (especially if!) there has been a really good, lively discussion: being in the moment for that kind of exchange is unlike anything else I do in terms of how focused but also flexible, how attentive to others but also on-task I need to be. I love it, and I really miss it already. I know we can have engaged and intellectually serious exchanges in our online format, but they won’t have the same rhythm, or perhaps any rhythm at all, who knows. Not having to be up and dressed and out the door early in the morning (or ever!) is some compensation, and I expect I will find more of a routine as we settle into the term, but (and I expect I’m going to be saying things like this a lot this term, so sorry for the repetition) it’s a strange new way of being a professor. As for specifics, well, we’re discussing Seamus Heaney’s “Digging” and Adrienne Rich’s “Aunt Jennifer’s Tiger” in my intro class this coming week, and in 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Hard Times (which I assigned this term because we ended up cutting it last term when we ‘pivoted’ to online). These are all texts I like a lot, though in my experience Hard Times is often a hard sell, even to students who otherwise like Dickens (which is never all of them, of course). Will I be able to communicate my enthusiasm and generate the kinds of discussions I aspire to in the classroom without being in the classroom? I guess I’ll find out. I’m trying to create recorded lectures that open up into writing prompts, rather than drawing conclusions, much as I would move in the classroom through laying out some ideas, contexts, or questions and then opening things up to their input. I am actually having some fun with this, though yet one more unknown is how effective my first attempts will be. I have the next two weeks of material nearly completed, so that buys me a bit of time: as I see what works and what doesn’t, and which approach to the lectures they prefer, I can adapt the next round accordingly.

As for specifics, well, we’re discussing Seamus Heaney’s “Digging” and Adrienne Rich’s “Aunt Jennifer’s Tiger” in my intro class this coming week, and in 19th-Century Fiction it’s time for Hard Times (which I assigned this term because we ended up cutting it last term when we ‘pivoted’ to online). These are all texts I like a lot, though in my experience Hard Times is often a hard sell, even to students who otherwise like Dickens (which is never all of them, of course). Will I be able to communicate my enthusiasm and generate the kinds of discussions I aspire to in the classroom without being in the classroom? I guess I’ll find out. I’m trying to create recorded lectures that open up into writing prompts, rather than drawing conclusions, much as I would move in the classroom through laying out some ideas, contexts, or questions and then opening things up to their input. I am actually having some fun with this, though yet one more unknown is how effective my first attempts will be. I have the next two weeks of material nearly completed, so that buys me a bit of time: as I see what works and what doesn’t, and which approach to the lectures they prefer, I can adapt the next round accordingly.

I also didn’t understand the relationship between Kate’s specific choices in the past and the outcome she hopes for from them. She believes (or Emilia believes) that she has some kind of mission to save the world, but as the novel wound on I got more confused about the nature of that mission and the metaphysics that presumably make sense of it, never mind how she and we are supposed to get from what she does then to what happens now. (It probably didn’t help my attempts to never mind all that and just go along with Newman’s unexplained model of time travel that I’ve been proofreading my husband’s book on determinism, which includes compelling arguments about the logical consequences of any speculative ‘what if’ re-imaginings of the past.) Newman is writing fiction, so she doesn’t necessarily have to meet a stringent philosophical standard, but there wasn’t even enough narrative coherence to her version to hold doubts at bay. As far as I can remember it, Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife (to which The Heavens has inevitably been compared) is every bit as metaphysically confusing and implausible but was at least an intensely gripping story.

I also didn’t understand the relationship between Kate’s specific choices in the past and the outcome she hopes for from them. She believes (or Emilia believes) that she has some kind of mission to save the world, but as the novel wound on I got more confused about the nature of that mission and the metaphysics that presumably make sense of it, never mind how she and we are supposed to get from what she does then to what happens now. (It probably didn’t help my attempts to never mind all that and just go along with Newman’s unexplained model of time travel that I’ve been proofreading my husband’s book on determinism, which includes compelling arguments about the logical consequences of any speculative ‘what if’ re-imaginings of the past.) Newman is writing fiction, so she doesn’t necessarily have to meet a stringent philosophical standard, but there wasn’t even enough narrative coherence to her version to hold doubts at bay. As far as I can remember it, Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife (to which The Heavens has inevitably been compared) is every bit as metaphysically confusing and implausible but was at least an intensely gripping story.