For the first time ever, I have assigned Scenes of Clerical Life in one of my classes—more accurately, a scene of clerical life, “Janet’s Repentance.” My re-reading of it some years ago had lodged the possibility of assigning the story (novella?) in my mind, but I hadn’t found what felt like the right opportunity until this term’s all-George Eliot, all the time seminar. We are discussing “Janet’s Repentance” in the seminar this week, so I thought that was a good enough reason to lift this post out of the archives.

For the first time ever, I have assigned Scenes of Clerical Life in one of my classes—more accurately, a scene of clerical life, “Janet’s Repentance.” My re-reading of it some years ago had lodged the possibility of assigning the story (novella?) in my mind, but I hadn’t found what felt like the right opportunity until this term’s all-George Eliot, all the time seminar. We are discussing “Janet’s Repentance” in the seminar this week, so I thought that was a good enough reason to lift this post out of the archives.

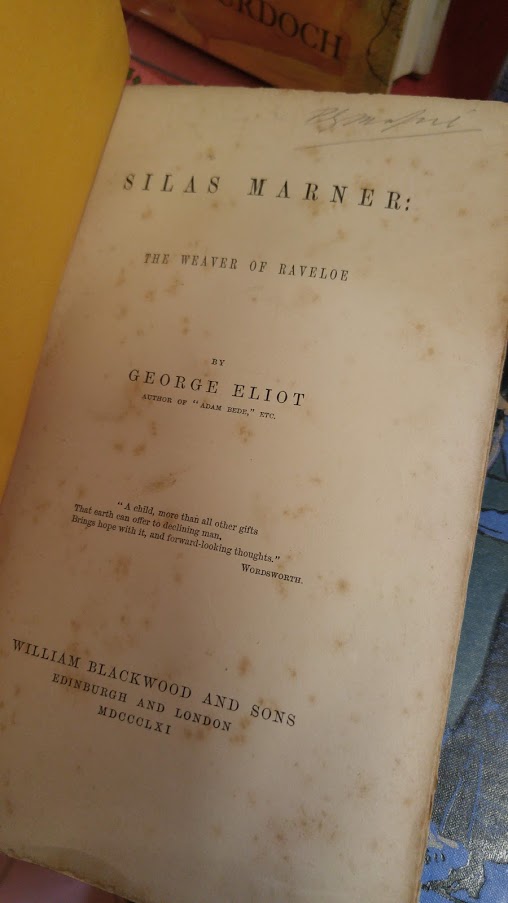

I’m not sure when I last read George Eliot’s first published fiction, Scenes of Clerical Life. It might have been as much as 15 or 20 years ago that I read any of the stories right through, though I have certainly dipped into “Amos Barton” once or twice when thinking or writing about her realism and her intrusive narrator. I picked the book off my shelf again this week because I have been thinking (and will be writing) about scenes of visiting in Eliot’s novels. So many of her climactic moments are set up that way, with a sympathetic visitor bringing comfort or guidance to someone in crisis: Dinah visiting Hetty in prison in Adam Bede, for instance; Lucy visiting Maggie near the end of The Mill on the Floss; perhaps most notably, Dorothea visiting Rosamond in Chapter 81 of Middlemarch. The key thing, of course, is that these are human, rather than divine, “visitations” and thus neatly encapsulate her ongoing translation of religious beliefs into secular practices. As I was collecting examples, I had a vague memory of Edgar Tryan visiting Janet in “Janet’s Repentance,” so I thought I’d go back to the story and see what it adds to the pattern I’m exploring.

“Janet’s Repentance” is interesting for lots of reasons, including its grim account of Janet’s abusive marriage, which has driven her, in her misery and shame, to drink:

‘I’ll teach you to keep me waiting in the dark, you pale, staring fool!’ he said, advancing with his slow, drunken step. ‘What, you’ve been drinking again, have you? I’ll beat you into your senses.’

He laid his hand with a firm grip on her shoulder, turned, her round, and pushed her slowly before him along the passage and through the dining-room door, which stood open on their left hand.

There was a portrait of Janet’s mother, a grey-haired, dark-eyed old woman, in a neatly fluted cap, hanging over the mantelpiece. Surely the aged eyes take on a look of anguish as they see Janet — not trembling, no! it would be better if she trembled — standing stupidly unmoved in her great beauty while the heavy arm is lifted to strike her. The blow falls — another — and another. Surely the mother hears that cry — ‘O Robert! pity! pity!’

“Do you wonder,” asks our narrator, as the sordid tale unfolds, “how it was that things had come to this pass — what offence Janet had committed in the early years of marriage to rouse the brutal hatred of this man? . . . But do not believe,” she goes on,

“Do you wonder,” asks our narrator, as the sordid tale unfolds, “how it was that things had come to this pass — what offence Janet had committed in the early years of marriage to rouse the brutal hatred of this man? . . . But do not believe,” she goes on,

that it was anything either present or wanting in poor Janet that formed the motive of her husband’s cruelty. Cruelty, like every other vice, requires no motive outside itself — it only requires opportunity. . . . And an unloving, tyrannous, brutal man needs no motive to prompt his cruelty; he needs only the perpetual presence of a woman he can call his own.

“A woman he can call his own”: that remark is strongly reminiscent of Frances Power Cobbe’s powerful 1878 essay “Wife-Torture in England,” in which Cobbe emphasizes the corrupting effect of presumed “ownership”:

The general depreciation of women as a sex is bad enough, but in the matter we are considering [spousal abuse], the special depreciation of wives is more directly responsible for the outrages they endure. The notion that a man’s wife is his PROPERTY, in the sense in which a horse is his property . . . is the fatal root of incalculable evil and misery. Every brutal-minded man, and many a man who in other relations of his life is not brutal, entertains more or less vaguely the notion that his wife is his thing, and is ready to ask with indignation (as we read again and again in the police reports), of any one who interferes with his treatment of her, “May I not do what I will with my own?”

(If you’re interested in reading more on this aspect of Victorian marriage and its treatment in Victorian fiction — try Lisa Surridge’s Bleak Houses and Kate Lawson’s The Marked Body, both of which discuss “Janet’s Repentance.”)

It’s also interesting how recognizable George Eliot is here. Many of the things she does better (or at least more fully, or with greater finesse) in her later novels are here already, such as the patient unfolding of social context — the “thick description” within which her plots acquire so much more meaning than their simple actions might indicate — and the pulsation between individual moments and philosophical ideas, facilitated by the narrator’s commentary on the action. Just as, despite her protective camouflage, Eliot’s friends “IRL” knew her when they read her earliest fiction, any readers of The Mill on the Floss know they are in familiar company when they see this anticipation of the famous “men of maxims” passage:

It’s also interesting how recognizable George Eliot is here. Many of the things she does better (or at least more fully, or with greater finesse) in her later novels are here already, such as the patient unfolding of social context — the “thick description” within which her plots acquire so much more meaning than their simple actions might indicate — and the pulsation between individual moments and philosophical ideas, facilitated by the narrator’s commentary on the action. Just as, despite her protective camouflage, Eliot’s friends “IRL” knew her when they read her earliest fiction, any readers of The Mill on the Floss know they are in familiar company when they see this anticipation of the famous “men of maxims” passage:

Yet surely, surely the only true knowledge of our fellow-man is that which enables us to feel with him – which gives us a fine ear for the heart-pulses that are beating under the mere clothes of circumstance and opinion. Our subtlest analysis of schools and sects must miss the essential truth, unless it be lit up by the love that sees in all forms of human thought and work, the life and death struggles of separate human beings.

And Janet’s appeal to Mr. Tryan — “It is very difficult to know what to do: what ought I to do?” — is one that has echoes across Eliot’s oeuvre, including in a passage in Middlemarch that has long been central to my thinking about the broader question of religion in Eliot’s fiction: “Help me, pray,” says an overwrought Dorothea to Dr. Lydgate; “Tell me what I can do.”

The big difference, though, is that in Middlemarch the appeal may have the same impulse as a prayer (“an impulse which if she had been alone would have turned into a prayer”) but it is directed at a doctor, and it’s not even really his medical advice she wants but something more fundamentally human, some guidance about how to be in the circumstances. The transformation from sacred to secular is even more distinct in the climactic encounter between Dorothea and Rosamond much later in the novel. But in “Janet’s Repentance” not only is Janet asking a clergyman (and an Evangelical one, at that) for help, but his advice is religious advice — and it is not undercut, or translated into humanistic terms, by the narrator. David Lodge notes in his introduction to my Penguin edition that “Janet’s Repentance” is “a completely non-ironical account of a conversion from sinfulness to righteousness through the selfless endeavours of an Evangelical clergyman.” He goes on to suggest that Eliot’s “religion of Humanity” is just below the surface, but it’s certainly not visible the way it is in her later works. It’s true that Tryan’s kindly fellowship is essential to his success as a religious ambassador: “Blessed influence of one true loving human soul on another!” says the narrator. But it’s trust in God that Tryan recommends, and that brings Janet peace.

The ending of the story is a bit of a disappointment: like Anne Brontë’s Helen Huntingdon, Janet feels obliged to stand by her man as he pays the final price for his cruel and self-destructive behavior. I think that in both cases this affirmation of ‘proper’ wifely devotion is important to direct our attention to the sins of the husbands. Brontë has a more political point to make, though, about the structural as well as ideological failures of marriage, while Eliot’s story focuses us more on the internal moral life and on the redemptive value of compassion and faith. Janet also does not get the hard-earned Happily Ever After that Helen enjoys, at least, not in this life: as Lodge points out, Eliot “even compromised with her belief in immortality to the extent of allowing her hero and heroine a ‘sacred kiss of promise’ at the end.” Disappointing, as I said, and surprising, from an author who wrote so stringently about the immorality of acting on the basis of future expectations rather than immediate consequences:

The ending of the story is a bit of a disappointment: like Anne Brontë’s Helen Huntingdon, Janet feels obliged to stand by her man as he pays the final price for his cruel and self-destructive behavior. I think that in both cases this affirmation of ‘proper’ wifely devotion is important to direct our attention to the sins of the husbands. Brontë has a more political point to make, though, about the structural as well as ideological failures of marriage, while Eliot’s story focuses us more on the internal moral life and on the redemptive value of compassion and faith. Janet also does not get the hard-earned Happily Ever After that Helen enjoys, at least, not in this life: as Lodge points out, Eliot “even compromised with her belief in immortality to the extent of allowing her hero and heroine a ‘sacred kiss of promise’ at the end.” Disappointing, as I said, and surprising, from an author who wrote so stringently about the immorality of acting on the basis of future expectations rather than immediate consequences:

The notion that duty looks stern, but all the while has her hand full of sugar-plums, with which she will reward us by and by, is the favourite cant of optimists, who try to make out that this tangled wilderness of life has a plan as easy to trace as that of a Dutch garden; but it really undermines all true moral development by perpetually substituting something extrinsic as a motive to action, instead of the immediate impulse of love or justice, which alone makes an action truly moral.

Was she catering to her as-yet unconverted audience, do you suppose, in setting Janet up as a memorial to “one whose heart beat with true compassion, and whose lips were moved by fervent faith”? Or practicing what she herself preached by inhabiting, as fully as possible, a point of view different from her own?

Originally published January 7, 2015. The writing I was doing on visitations in George Eliot became (more or less) the essay “Middlemarch and the ‘Cry From Soul to Soul,'” published in Berfrois in August 2015. Sadly, Berfrois is no more, but the essay can also be found in my collection Widening the Skirts of Light, available as an e-book from Amazon & Kobo for the lowest price I was allowed to set.

As my ‘Victorian Woman Question’ seminar makes its way through The Mill on the Floss, I am very much missing the opportunity to engage in face to face discussion with everyone. It’s a novel that provokes delight, frustration, sorrow, and thought in so many ways–that raises so many complications for us, thematically and formally: it feels more difficult to choose topics and shape conversations for our online version of the class for The Mill on the Floss than it has felt for some of the other novels I have taught this way in the last few months, including (perhaps surprisingly) Middlemarch. But of course the novel itself is as wonderful as usual, and our readings for this past week included one of my favorite incidents: Mrs. Tulliver’s poignant attempt to hang on to her “chany.” It moved me even more this time: as the one-year anniversary of our COVID-inflicted isolation approaches, the things that connect us to each other and to our histories seem to me to be carrying more and more emotional weight. Here’s a post I wrote about Mrs. Tulliver’s “teraphim” almost a decade ago.

As my ‘Victorian Woman Question’ seminar makes its way through The Mill on the Floss, I am very much missing the opportunity to engage in face to face discussion with everyone. It’s a novel that provokes delight, frustration, sorrow, and thought in so many ways–that raises so many complications for us, thematically and formally: it feels more difficult to choose topics and shape conversations for our online version of the class for The Mill on the Floss than it has felt for some of the other novels I have taught this way in the last few months, including (perhaps surprisingly) Middlemarch. But of course the novel itself is as wonderful as usual, and our readings for this past week included one of my favorite incidents: Mrs. Tulliver’s poignant attempt to hang on to her “chany.” It moved me even more this time: as the one-year anniversary of our COVID-inflicted isolation approaches, the things that connect us to each other and to our histories seem to me to be carrying more and more emotional weight. Here’s a post I wrote about Mrs. Tulliver’s “teraphim” almost a decade ago. One of the many things that make reading George Eliot at once so challenging and so satisfying is her resistance to simplicity–especially moral simplicity. It’s difficult to sit in judgment on her characters. For one thing, she’s usually not just one but two or three steps ahead: she’s seen and analyzed their flaws with emphatic clarity, but she’s also put them in context, explaining their histories and causes and effects and pointing out to us that we aren’t really that different ourselves. Often the characters themselves are in conflict over their failings (think Bulstrode), and when they’re not, at least they can be shaken out of them temporarily, swept into the stream of the novel’s moral current (think Rosamond, or in a different way, Hetty). But these are the more grandiose examples, the ones we know we have to struggle to understand and embrace with our moral theories. Her novels also feature pettier and often more comically imperfect characters who are more ineffectual than damaging, or whose flaws turn out, under the right circumstances, to be strengths. In The Mill on the Floss, Mrs Glegg is a good example of someone who comes through in the end, the staunch family pride that makes her annoyingly funny early on ultimately putting her on the right side in the conflict that tears the novel apart.

One of the many things that make reading George Eliot at once so challenging and so satisfying is her resistance to simplicity–especially moral simplicity. It’s difficult to sit in judgment on her characters. For one thing, she’s usually not just one but two or three steps ahead: she’s seen and analyzed their flaws with emphatic clarity, but she’s also put them in context, explaining their histories and causes and effects and pointing out to us that we aren’t really that different ourselves. Often the characters themselves are in conflict over their failings (think Bulstrode), and when they’re not, at least they can be shaken out of them temporarily, swept into the stream of the novel’s moral current (think Rosamond, or in a different way, Hetty). But these are the more grandiose examples, the ones we know we have to struggle to understand and embrace with our moral theories. Her novels also feature pettier and often more comically imperfect characters who are more ineffectual than damaging, or whose flaws turn out, under the right circumstances, to be strengths. In The Mill on the Floss, Mrs Glegg is a good example of someone who comes through in the end, the staunch family pride that makes her annoyingly funny early on ultimately putting her on the right side in the conflict that tears the novel apart. Then there’s her sister Bessy, Mrs Tulliver, who is easy to dismiss as foolish and weak, but to whom I have become increasingly sympathetic over the years. Mrs Tulliver is foolish and weak, but in her own way she cleaves to the same values as the novel overall: family and memory, the “twining” of our affections “round those old inferior things.” In class tomorrow we are moving through Books III and IV, in which the Tulliver family fortunes collapse, along with Mr Tulliver himself, and the relatives gather to see what’s to be done. The way the prosperous sisters patronize poor Bessy is as devastatingly revealing about them as it is crushing to her hopes that they’ll pitch in to keep some of her household goods from being put up to auction:

Then there’s her sister Bessy, Mrs Tulliver, who is easy to dismiss as foolish and weak, but to whom I have become increasingly sympathetic over the years. Mrs Tulliver is foolish and weak, but in her own way she cleaves to the same values as the novel overall: family and memory, the “twining” of our affections “round those old inferior things.” In class tomorrow we are moving through Books III and IV, in which the Tulliver family fortunes collapse, along with Mr Tulliver himself, and the relatives gather to see what’s to be done. The way the prosperous sisters patronize poor Bessy is as devastatingly revealing about them as it is crushing to her hopes that they’ll pitch in to keep some of her household goods from being put up to auction: Early in these scenes Maggie finds that her mother’s “reproaches against her father…neutralized all her pity for griefs about table-cloths and china”; the aunts and uncles are pitiless in their indifference to Bessy’s misplaced priorities. I used to find her pathetic clinging to these domestic trifles in the face of much graver difficulties just more evidence that she belonged to the “narrow, ugly, grovelling existence, which even calamity does not elevate”–the environment that surrounds Tom and Maggie, but especially Maggie, with “oppressive narrowness,” with eventually catastrophic results. She also seemed a specimen of the kind of shallow-minded, materialistic woman George Eliot’s heroines aspire not to be. But she’s not really materialistic and shallow. She doesn’t want the teapot because it’s silver: she wants it because it’s tangible evidence of her ties to her past, of the choices and commitments and loves and hopes that have made up her life and identity. She’s not really mourning the loss of her “chany” and table linens; she’s mourning her severance from her history.

Early in these scenes Maggie finds that her mother’s “reproaches against her father…neutralized all her pity for griefs about table-cloths and china”; the aunts and uncles are pitiless in their indifference to Bessy’s misplaced priorities. I used to find her pathetic clinging to these domestic trifles in the face of much graver difficulties just more evidence that she belonged to the “narrow, ugly, grovelling existence, which even calamity does not elevate”–the environment that surrounds Tom and Maggie, but especially Maggie, with “oppressive narrowness,” with eventually catastrophic results. She also seemed a specimen of the kind of shallow-minded, materialistic woman George Eliot’s heroines aspire not to be. But she’s not really materialistic and shallow. She doesn’t want the teapot because it’s silver: she wants it because it’s tangible evidence of her ties to her past, of the choices and commitments and loves and hopes that have made up her life and identity. She’s not really mourning the loss of her “chany” and table linens; she’s mourning her severance from her history. I think I understand her better than I used to, and feel more tolerant of her bewildered grief, because I have “teraphim,” or “household gods,” of my own, things that I would grieve the loss of quite out of proportion to their actual value. They are things that tie me, too, to my history, as well as to memories of people in my life. I have a teapot, for instance, that was my grandmother’s; every time I use it, or the small array of cups and saucers and plates that remain from the same set (my grandmother was hard on her dishes!) I think of her and feel more like my old self. I have a pair of Denby mugs that were gifts from my parents many years ago, tributes to my childhood fascination with English history: one has Hampton Court on it, the other, the Tower–these, too, have become talismanic, having survived multiple moves. If I dropped one, I’d be devastated, and not just because as far as we’ve ever been able to find out, they would be impossible to replace. “Very commonplace, even ugly, that furniture of our early home might look if it were put up to auction,” remarks the narrator with typical prescience, shortly before financial calamity hits the Tullivers, but there’s no special merit in “striving after something better and better” at the expense of “the loves and sanctities of our life,” with their “deep immovable roots in memory.” Sometimes a teapot is not just a teapot.

I think I understand her better than I used to, and feel more tolerant of her bewildered grief, because I have “teraphim,” or “household gods,” of my own, things that I would grieve the loss of quite out of proportion to their actual value. They are things that tie me, too, to my history, as well as to memories of people in my life. I have a teapot, for instance, that was my grandmother’s; every time I use it, or the small array of cups and saucers and plates that remain from the same set (my grandmother was hard on her dishes!) I think of her and feel more like my old self. I have a pair of Denby mugs that were gifts from my parents many years ago, tributes to my childhood fascination with English history: one has Hampton Court on it, the other, the Tower–these, too, have become talismanic, having survived multiple moves. If I dropped one, I’d be devastated, and not just because as far as we’ve ever been able to find out, they would be impossible to replace. “Very commonplace, even ugly, that furniture of our early home might look if it were put up to auction,” remarks the narrator with typical prescience, shortly before financial calamity hits the Tullivers, but there’s no special merit in “striving after something better and better” at the expense of “the loves and sanctities of our life,” with their “deep immovable roots in memory.” Sometimes a teapot is not just a teapot. Though I suppose in a technical way the bicentenary year really ended with George Eliot’s birthday on November 22, why stop celebrating before we have to? My only regret is that I’m not actually teaching any of her novels this term–in fact, because of my sabbatical, I haven’t taught any George Eliot in 2019 at all! Shocking! So I haven’t been able to integrate any bicentenary activities into my classroom time. I did point out to the students presenting in Women & Detective Fiction on November 22 that it was an especially auspicious day, but they didn’t seem convinced or otherwise excited. 🙂

Though I suppose in a technical way the bicentenary year really ended with George Eliot’s birthday on November 22, why stop celebrating before we have to? My only regret is that I’m not actually teaching any of her novels this term–in fact, because of my sabbatical, I haven’t taught any George Eliot in 2019 at all! Shocking! So I haven’t been able to integrate any bicentenary activities into my classroom time. I did point out to the students presenting in Women & Detective Fiction on November 22 that it was an especially auspicious day, but they didn’t seem convinced or otherwise excited. 🙂 And speaking of excellent company, also in honour of the bicentenary I was invited to be a guest on the CBC Radio show ‘Sunday Edition,’ to talk to host Michael Enright about George Eliot and Middlemarch. You can

And speaking of excellent company, also in honour of the bicentenary I was invited to be a guest on the CBC Radio show ‘Sunday Edition,’ to talk to host Michael Enright about George Eliot and Middlemarch. You can  As I browsed through it in preparation for the interview, I stopped to reread many of the moments I love the best–the description of Lydgate’s discovering his vocation in Chapter XV, with its poignant commentary on “the multitude of middle-aged men who go about their vocations in a daily course determined for them much in the same way as the tie of their cravats,” for instance:

As I browsed through it in preparation for the interview, I stopped to reread many of the moments I love the best–the description of Lydgate’s discovering his vocation in Chapter XV, with its poignant commentary on “the multitude of middle-aged men who go about their vocations in a daily course determined for them much in the same way as the tie of their cravats,” for instance: I don’t know if Middlemarch is, as the CBC headline proposes, “the greatest English novel of all time.” I think Eliot (for reasons I discuss in the interview) can reasonably be called the greatest Victorian novelist, and Middlemarch is certainly her greatest book, but there are other models of the novel and other ideas of greatness: as Henry James said, the house of fiction has many windows. One of the things I said to Michael Enright during our conversation was that our judgments of any given novel will depend on what we think the novel (both the particular example and, I think, the genre as a whole) is for. I’m not (much) interested in defending Middlemarch to people who don’t like it, but I am always happy to explain what I think is wonderful about it. I wouldn’t be much good at my job, also, if I didn’t believe we can all learn to read books–all books, any book–better than we do, if someone will just help us along. I hope my interview does some of that work for listeners, and of course for readers who want even more help, there are lots of resources at my

I don’t know if Middlemarch is, as the CBC headline proposes, “the greatest English novel of all time.” I think Eliot (for reasons I discuss in the interview) can reasonably be called the greatest Victorian novelist, and Middlemarch is certainly her greatest book, but there are other models of the novel and other ideas of greatness: as Henry James said, the house of fiction has many windows. One of the things I said to Michael Enright during our conversation was that our judgments of any given novel will depend on what we think the novel (both the particular example and, I think, the genre as a whole) is for. I’m not (much) interested in defending Middlemarch to people who don’t like it, but I am always happy to explain what I think is wonderful about it. I wouldn’t be much good at my job, also, if I didn’t believe we can all learn to read books–all books, any book–better than we do, if someone will just help us along. I hope my interview does some of that work for listeners, and of course for readers who want even more help, there are lots of resources at my

The

The

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

That sense of reconnecting with my former self is part of what always makes time in London feel so special to me. After

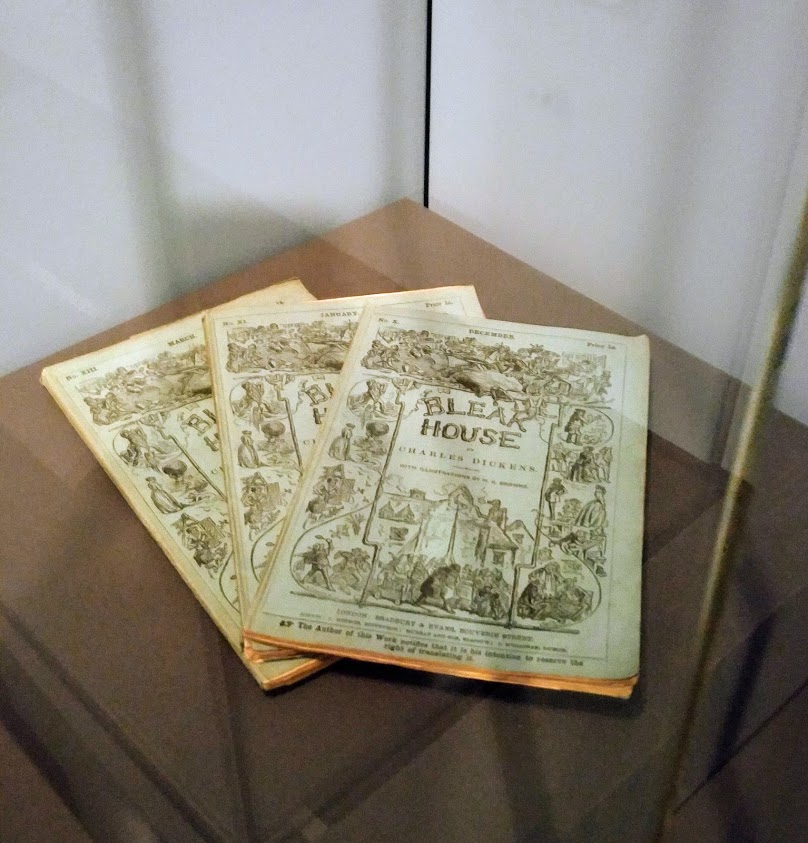

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon.

But why? Not just why did seeing Arbury Hall move me so much but why was I so emotionally susceptible to seeing those bits of Bleak House or standing next to Dickens’s desk? I am used to feeling excited when I see things or visit places that are real parts of the historical stories I have known for so long, but I have not previously been startled into poignancy in quite the same way. Is it just age? I do seem, now that I’m into my fifties, to be more readily tearful, which is no doubt partly hormones but which I think is also because of the keen awareness of time passing that has come with other changes in my life, such as my children both graduating from high school and moving out of the house–an ongoing process at this point but still a significant transition for all of us. Also, as I approach twenty-five years of working at Dalhousie, and as so many of my senior colleagues retire and disappear from my day-to-day life, I have had to acknowledge that I am now “senior” here, and that my own next big professional milestone will also be retirement–it’s not imminent, but it’s certainly visible on the horizon. Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

Perhaps it’s these contexts that gave greater resonance to seeing these tangible pieces of other people’s lives, especially people who have made such a mark on mine. Though I have usually considered writers’ biographies of secondary interest to their work, there was something powerful for me this time in being reminded that Dickens and Eliot were both very real people who had, and whose books had, a real physical presence in the world. People sometimes talk dismissively about fiction as if it is insubstantial, inessential, peripheral to to the “real world” (a term often deployed to mean utilitarian business of some kind). But words and ideas and books are very real things, and they make a very real difference in the world: they make us think and feel differently about it and thus act differently in it. Another of my London stops this time was at

In retrospect, I’m glad my pitch for a article reporting back on the George Eliot Bicentenary Conference was rejected: the cognitive dissonance I struggled with during the conference was strong enough that I have been puzzling over how or whether to write about it even here, in relative obscurity and without being answerable to anyone else for whatever it is that I come up with to say.

In retrospect, I’m glad my pitch for a article reporting back on the George Eliot Bicentenary Conference was rejected: the cognitive dissonance I struggled with during the conference was strong enough that I have been puzzling over how or whether to write about it even here, in relative obscurity and without being answerable to anyone else for whatever it is that I come up with to say.

Each of the presenters on our panel addressed quite a different “application” for George Eliot. I spoke about what I see as reasons for but also the difficulties with “pitching” her work to the kind of bookish public I have been trying to write for–at left is my design for a George Eliot tote bag meant to illustrate the case I made that her books are not, as too often assumed,

Each of the presenters on our panel addressed quite a different “application” for George Eliot. I spoke about what I see as reasons for but also the difficulties with “pitching” her work to the kind of bookish public I have been trying to write for–at left is my design for a George Eliot tote bag meant to illustrate the case I made that her books are not, as too often assumed,

It isn’t exactly that I want no part of it, though. As I hope I have also made clear here over the years, my own intellectual life has been shaped and enriched by many kinds of academic scholarship (though

It isn’t exactly that I want no part of it, though. As I hope I have also made clear here over the years, my own intellectual life has been shaped and enriched by many kinds of academic scholarship (though  I’m about three quarters of the way through my second reading of Woolf’s The Years. It is still pretty slow going for me, slower than before even, because instead of wondering what the heck is happening (or, as more often seems to be the case in the novel, not happening) I am trying to figure it out with the help of the various sources I’ve been reading around in and also the amply introduced and copiously annotated Cambridge edition–of its 870 pages, only 388 are actually The Years. That’s not really a sufficient excuse for my not having read once more to the end, though: the truth is that The Years engages me much more in theory than in practice. I quite like reading about it, but

I’m about three quarters of the way through my second reading of Woolf’s The Years. It is still pretty slow going for me, slower than before even, because instead of wondering what the heck is happening (or, as more often seems to be the case in the novel, not happening) I am trying to figure it out with the help of the various sources I’ve been reading around in and also the amply introduced and copiously annotated Cambridge edition–of its 870 pages, only 388 are actually The Years. That’s not really a sufficient excuse for my not having read once more to the end, though: the truth is that The Years engages me much more in theory than in practice. I quite like reading about it, but  I would explain the novel’s failure on similar terms as Lee but with less subtlety: The Years is a failure because (deliberately or not) Woolf’s theory of the novel (including “her feeling that art should subsume politics”) was genuinely incompatible with her aims for this particular novel. She wanted (and this is pretty clear from what I’ve read of her diaries around this period) to write a “novel of purpose” (defined by Amanda Claybaugh in The Novel of Purpose as a novel “that sought to intervene in the contemporary world”). It seems plausible, and some scholars make this connection explicitly, that she was motivated to breach the wall between art and politics because of

I would explain the novel’s failure on similar terms as Lee but with less subtlety: The Years is a failure because (deliberately or not) Woolf’s theory of the novel (including “her feeling that art should subsume politics”) was genuinely incompatible with her aims for this particular novel. She wanted (and this is pretty clear from what I’ve read of her diaries around this period) to write a “novel of purpose” (defined by Amanda Claybaugh in The Novel of Purpose as a novel “that sought to intervene in the contemporary world”). It seems plausible, and some scholars make this connection explicitly, that she was motivated to breach the wall between art and politics because of  I’m not saying anything original about that process, which is well known. I’m just trying to clarify why I think (and why I think Woolf thinks) the result is a failure. “How to do that will be one of the problems,” she comments in her diary early in the writing process; “I mean the intellectual argument in the form of art: I mean how give ordinary waking Arnold Bennett life the form of art? These are rich hard problems for my four months ahead.” My take is simply that she did not solve these problems, or she refused to solve them, because she could not reconcile her means with her end. To put it bluntly, she could not bring herself to write the kind of fiction that would get the job done. Fiction can’t intervene effectively in contemporary life if nobody knows what you mean by it. Burying the meaning, as she did (“the rest under water”), however artistically consistent, is polemically (politically) stifling, or at least muffling. Obscurity is incompatible with activism.

I’m not saying anything original about that process, which is well known. I’m just trying to clarify why I think (and why I think Woolf thinks) the result is a failure. “How to do that will be one of the problems,” she comments in her diary early in the writing process; “I mean the intellectual argument in the form of art: I mean how give ordinary waking Arnold Bennett life the form of art? These are rich hard problems for my four months ahead.” My take is simply that she did not solve these problems, or she refused to solve them, because she could not reconcile her means with her end. To put it bluntly, she could not bring herself to write the kind of fiction that would get the job done. Fiction can’t intervene effectively in contemporary life if nobody knows what you mean by it. Burying the meaning, as she did (“the rest under water”), however artistically consistent, is polemically (politically) stifling, or at least muffling. Obscurity is incompatible with activism. Though Holtby may be the pivot on which Woolf’s failure turns, it’s Vera Brittain’s Honourable Estate, not Holtby’s South Riding, that provides the most illuminating comparison to The Years, because it illustrates the perils of doing just what Woolf wouldn’t do: explaining everything. Where The Years (as many critics have noted) takes but subverts the form of the family saga, Honourable Estate embraces it. It covers nearly the same span of time as The Years and many of the same issues (the suffrage movement, the war, challenges to patriarchal dominance in the family, the hazards of sexuality, especially for young women, etc.). I wrote about Honourable Estate here before (

Though Holtby may be the pivot on which Woolf’s failure turns, it’s Vera Brittain’s Honourable Estate, not Holtby’s South Riding, that provides the most illuminating comparison to The Years, because it illustrates the perils of doing just what Woolf wouldn’t do: explaining everything. Where The Years (as many critics have noted) takes but subverts the form of the family saga, Honourable Estate embraces it. It covers nearly the same span of time as The Years and many of the same issues (the suffrage movement, the war, challenges to patriarchal dominance in the family, the hazards of sexuality, especially for young women, etc.). I wrote about Honourable Estate here before ( Here’s just one of many potential examples showing how differently these novels approach the same material. Both include sections that take place in 1908, the year of the great “

Here’s just one of many potential examples showing how differently these novels approach the same material. Both include sections that take place in 1908, the year of the great “

In that earlier post on Honourable Estate I discussed Marion Shaw’s essay “Feminism and Fiction between the Wars: Winifred Holtby and Virginia Woolf,” saying that it “cautions us (me!) against underestimating the art of a novel like Honourable Estate.” Throwing that caution to the wind, I will say frankly that I think Honourable Estate is not a good novel (see, I knew we’d work our way back to the problem of measuring literary quality). It just seems so painfully obvious from start to finish! On its own terms, though, I’m not sure it is actually a failure. Unlike Woolf, Brittain had an uncompromised mission as a novelist. In her own foreword to Honourable Estate, Brittain explains,

In that earlier post on Honourable Estate I discussed Marion Shaw’s essay “Feminism and Fiction between the Wars: Winifred Holtby and Virginia Woolf,” saying that it “cautions us (me!) against underestimating the art of a novel like Honourable Estate.” Throwing that caution to the wind, I will say frankly that I think Honourable Estate is not a good novel (see, I knew we’d work our way back to the problem of measuring literary quality). It just seems so painfully obvious from start to finish! On its own terms, though, I’m not sure it is actually a failure. Unlike Woolf, Brittain had an uncompromised mission as a novelist. In her own foreword to Honourable Estate, Brittain explains, What an uncomfortable conclusion, though: even if I’m reluctant to let Woolf (or Austen) set the evaluative terms, I find it hard to concede that literary merit consists solely of doing whatever it is that you set out to do. I have argued (at some length!)

What an uncomfortable conclusion, though: even if I’m reluctant to let Woolf (or Austen) set the evaluative terms, I find it hard to concede that literary merit consists solely of doing whatever it is that you set out to do. I have argued (at some length!)  Tomorrow we start our work on Adam Bede in my 19th-Century Fiction class. As I was rereading the opening chapters last week, I tweeted, a bit facetiously, that you could probably “launch a successful attack on the whole foolish ‘show, don’t tell’ myth using excerpts from Adam Bede alone.” This was in part a delayed reaction to a comment on my post about Lillian Boxfish Takes A Walk: “it didn’t work for me at all as fiction,” Irene said; “A lot of telling, not showing.” To which I replied, “I’m a fan of telling. How could I not be, as a Victorianist?” Because when people invoke this supposed rule, what they usually seem to mean is that good writing should be dramatic, not descriptive, and that, above all, it should avoid extended passages of exposition — and what would Victorian fiction be without description and exposition? Frankly, I’ve also read a few too many

Tomorrow we start our work on Adam Bede in my 19th-Century Fiction class. As I was rereading the opening chapters last week, I tweeted, a bit facetiously, that you could probably “launch a successful attack on the whole foolish ‘show, don’t tell’ myth using excerpts from Adam Bede alone.” This was in part a delayed reaction to a comment on my post about Lillian Boxfish Takes A Walk: “it didn’t work for me at all as fiction,” Irene said; “A lot of telling, not showing.” To which I replied, “I’m a fan of telling. How could I not be, as a Victorianist?” Because when people invoke this supposed rule, what they usually seem to mean is that good writing should be dramatic, not descriptive, and that, above all, it should avoid extended passages of exposition — and what would Victorian fiction be without description and exposition? Frankly, I’ve also read a few too many  If your ideal fiction is not analytical in these ways, then showing might be enough for you. But that means your novels will never include anything like Chapter 15 of Middlemarch — in which almost nothing actually happens, but we, as readers, learn an enormous amount — or, to get back to Adam Bede, anything like its Chapter 15, “The Two Bed-Chambers,” which is a stunning set piece of characterization. It includes both showing and telling. The actions of both Hetty and Dinah, for instance, speak volumes about who they are: most obviously, Hetty stares into her mirror while Dinah gazes out the window. The narrator layers meaning onto their actions with pointed descriptions — Hetty’s “pigeon-like stateliness” as she paces back and forth in her shabby faux-finery, for instance, and Dinah’s tranquility as she feels “the presence of a Love and Sympathy deeper and more tender than was breathed from the earth and sky.” We are brought close into each character’s consciousness, and then drawn out again to a broader perception, which is the characteristic pulse of George Eliot’s fiction, and running through it all is her perspicacious commentary:

If your ideal fiction is not analytical in these ways, then showing might be enough for you. But that means your novels will never include anything like Chapter 15 of Middlemarch — in which almost nothing actually happens, but we, as readers, learn an enormous amount — or, to get back to Adam Bede, anything like its Chapter 15, “The Two Bed-Chambers,” which is a stunning set piece of characterization. It includes both showing and telling. The actions of both Hetty and Dinah, for instance, speak volumes about who they are: most obviously, Hetty stares into her mirror while Dinah gazes out the window. The narrator layers meaning onto their actions with pointed descriptions — Hetty’s “pigeon-like stateliness” as she paces back and forth in her shabby faux-finery, for instance, and Dinah’s tranquility as she feels “the presence of a Love and Sympathy deeper and more tender than was breathed from the earth and sky.” We are brought close into each character’s consciousness, and then drawn out again to a broader perception, which is the characteristic pulse of George Eliot’s fiction, and running through it all is her perspicacious commentary: I know that what some readers object to in Eliot’s style of telling is that she doesn’t seem to leave us to draw our own conclusions about her characters: her commentary usually steers us firmly in a particular direction. Her narrator is much less forgiving than Dinah, for example, about Hetty’s vanity, and so too is Mrs. Poyser, who sees Hetty’s “moral deficiencies” quite clearly. It’s not that she doesn’t leave us plenty to think about, though. Adam Bede dedicates much more than this one chapter to analyzing Hetty’s character and motives, for example, as well as to exploring the effect on them of her specific circumstances. A great deal of effort, in other words, goes into understanding Hetty — including the unarguable fact of her vanity, which means not just her pleasure in her own beauty but her inability to tell any story without herself at the center of it. Also, we know that “Hetty could have cast all her past life behind her and never cared to be reminded of it again” — which, in Eliot’s world, means she is morally unmoored. (“If the past is not to bind us,” as Maggie Tulliver will say in Eliot’s next novel, “where shall duty lie?”) What, though, is the relationship between this deep understanding (the kind required by Eliot’s theory of determinism) and forgiveness? If we can explain so thoroughly what someone does so, and if we are under a moral obligation to sympathize with them, what happens to accountability, to blame, to justice? If you know where Hetty’s journey takes her, and why, then you know how painfully these questions arise in Adam Bede.

I know that what some readers object to in Eliot’s style of telling is that she doesn’t seem to leave us to draw our own conclusions about her characters: her commentary usually steers us firmly in a particular direction. Her narrator is much less forgiving than Dinah, for example, about Hetty’s vanity, and so too is Mrs. Poyser, who sees Hetty’s “moral deficiencies” quite clearly. It’s not that she doesn’t leave us plenty to think about, though. Adam Bede dedicates much more than this one chapter to analyzing Hetty’s character and motives, for example, as well as to exploring the effect on them of her specific circumstances. A great deal of effort, in other words, goes into understanding Hetty — including the unarguable fact of her vanity, which means not just her pleasure in her own beauty but her inability to tell any story without herself at the center of it. Also, we know that “Hetty could have cast all her past life behind her and never cared to be reminded of it again” — which, in Eliot’s world, means she is morally unmoored. (“If the past is not to bind us,” as Maggie Tulliver will say in Eliot’s next novel, “where shall duty lie?”) What, though, is the relationship between this deep understanding (the kind required by Eliot’s theory of determinism) and forgiveness? If we can explain so thoroughly what someone does so, and if we are under a moral obligation to sympathize with them, what happens to accountability, to blame, to justice? If you know where Hetty’s journey takes her, and why, then you know how painfully these questions arise in Adam Bede. My point, I guess, is that this central problem of the novel is vivid to us — it matters to us — in part because of what we have been told. It is an intellectual problem, not (to borrow from Darwin’s post) a “scratch-and-sniff” one. Yet, having said that, it’s absolutely true that we feel its urgency in part because the narrator gets out of the way at crucial dramatic moments, such as during the novel’s second great set piece with Dinah and Hetty much, much later, in Hetty’s prison cell:

My point, I guess, is that this central problem of the novel is vivid to us — it matters to us — in part because of what we have been told. It is an intellectual problem, not (to borrow from Darwin’s post) a “scratch-and-sniff” one. Yet, having said that, it’s absolutely true that we feel its urgency in part because the narrator gets out of the way at crucial dramatic moments, such as during the novel’s second great set piece with Dinah and Hetty much, much later, in Hetty’s prison cell: Our reading for today in The Victorian ‘Woman Question’ was Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1850 short story “

Our reading for today in The Victorian ‘Woman Question’ was Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1850 short story “ Gaskell’s most obvious literary device in the story is pathos.

Gaskell’s most obvious literary device in the story is pathos.  Gaskell was a minister’s wife and “Lizzie Leigh” casts its story of forgiveness in explicitly Christian terms. Susan “is not one to judge and scorn the sinner,” Anne insists to her son Will, for instance (soothing his horror that she has shared Lizzie’s story with one he sees as “downright holy”); “She’s too deep read in her New Testament for that.” What I think is so powerful about the story is the way Gaskell pits Anne’s (and Susan’s) definition of Christian virtue against the “hard, stern, and inflexible” judgments, first of Anne’s husband James (who had forbidden her to seek out “her poor, sinning child”) and then of Will, who has inherited his father’s patriarchal role and with it his rigid righteousness. Anne grows into her own authority as the story progresses, eventually confronting Will directly:

Gaskell was a minister’s wife and “Lizzie Leigh” casts its story of forgiveness in explicitly Christian terms. Susan “is not one to judge and scorn the sinner,” Anne insists to her son Will, for instance (soothing his horror that she has shared Lizzie’s story with one he sees as “downright holy”); “She’s too deep read in her New Testament for that.” What I think is so powerful about the story is the way Gaskell pits Anne’s (and Susan’s) definition of Christian virtue against the “hard, stern, and inflexible” judgments, first of Anne’s husband James (who had forbidden her to seek out “her poor, sinning child”) and then of Will, who has inherited his father’s patriarchal role and with it his rigid righteousness. Anne grows into her own authority as the story progresses, eventually confronting Will directly: There are definitely things about “Lizzie Leigh” that are hard to take, including the fate of “the little, unconscious sacrifice, whose early calling-home had reclaimed her poor, wandering mother” as well as the extreme seclusion that is Lizzie’s fate after her reclamation. She’s not (like Hetty, or Little Emily) sent entirely out of her world, but Gaskell can’t quite imagine a place for her fully in it either. What I love about “Lizzie Leigh,” though, is the same thing I love about Mary Barton, North and South, and

There are definitely things about “Lizzie Leigh” that are hard to take, including the fate of “the little, unconscious sacrifice, whose early calling-home had reclaimed her poor, wandering mother” as well as the extreme seclusion that is Lizzie’s fate after her reclamation. She’s not (like Hetty, or Little Emily) sent entirely out of her world, but Gaskell can’t quite imagine a place for her fully in it either. What I love about “Lizzie Leigh,” though, is the same thing I love about Mary Barton, North and South, and