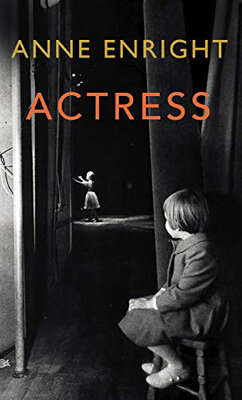

The headline, the article, it all points to one thing, the actress and her overshadowed child. The picture adds to the lie that I am a poor copy of my mother, that she was timeless, and I am not—the iconic gives birth to the merely human. But that was not how it was between us. That is not how we felt about ourselves.

The headline, the article, it all points to one thing, the actress and her overshadowed child. The picture adds to the lie that I am a poor copy of my mother, that she was timeless, and I am not—the iconic gives birth to the merely human. But that was not how it was between us. That is not how we felt about ourselves.

Anne Enright’s Actress reads swiftly and piercingly, and yet it also felt fleeting to me: I finished it without any sense that it had gone deep or would linger with me. There’s a lot that’s interesting and well told in this story of a glamorous but (or, the novel suggests, therefore) unstable mother and her daughter and their different but related struggles with her fame and its side-effects. The most powerful element of the novel for me was its exploration of the many ways women’s beauty, ambition, and vulnerability are exploited: to act, to perform, is to court admiration that the novel shows is always going to be a two-edged sword—to require and reward exposure that makes unwanted attention impossible to avoid. There is a lot of poignancy in the story of Katherine O’Dell, who puts on her beautiful public face and plays the part of an Irish heroine for an audience that is demanding, fickle, and judgmental. There’s corresponding pathos in her daughter Norah’s struggles to figure out who she can be and also, belatedly, to understand who her mother really was and how her own identity—she is born of a father Katherine refuses, for reasons we eventually learn, to acknowledge—embodies both the best and the worst of her mother’s fraught history.

Much as I was moved by both Katherine and Norah and engaged by the meticulously evoked historical and theatrical settings of the novel, though, I found the reading experience fragmented, the pieces of the novel difficult to integrate. Maybe if I reread it or thought harder about it I would understand why some of the bits and pieces are there, or why they are ordered in the novel as they are. I admit that right now I am a bit impatient with novelists who leave what feels like too much of that work up to me. I miss exposition, linearity, confidence that the novel as a form is robust enough to be “traditional” in these ways and still new. Actress is not by any means as conspicuously piecemeal as some recent novels, and it isn’t really minimalist, just condensed and somewhat episodic. Maybe it should be enough that it made me feel for the characters, and that Katherine especially seemed vivid enough to be more than a type—though I did feel at times that her pathos and melodrama and ‘madness’ (as her daughter characterizes it) verged on cliché. Is it the red hair (acquired to boost her ‘Irish’ identity) that meant I kept picturing her as Beth Harmon in The Queen’s Gambit? That, and her drinking and her flamboyance and her misery and her endless performance as a character in her own drama: that she lacks (or can’t rely on) her authentic self is part of Katherine’s tragedy, but it also made her poor company, and Norah is similarly, if more quietly, histrionic.

Much as I was moved by both Katherine and Norah and engaged by the meticulously evoked historical and theatrical settings of the novel, though, I found the reading experience fragmented, the pieces of the novel difficult to integrate. Maybe if I reread it or thought harder about it I would understand why some of the bits and pieces are there, or why they are ordered in the novel as they are. I admit that right now I am a bit impatient with novelists who leave what feels like too much of that work up to me. I miss exposition, linearity, confidence that the novel as a form is robust enough to be “traditional” in these ways and still new. Actress is not by any means as conspicuously piecemeal as some recent novels, and it isn’t really minimalist, just condensed and somewhat episodic. Maybe it should be enough that it made me feel for the characters, and that Katherine especially seemed vivid enough to be more than a type—though I did feel at times that her pathos and melodrama and ‘madness’ (as her daughter characterizes it) verged on cliché. Is it the red hair (acquired to boost her ‘Irish’ identity) that meant I kept picturing her as Beth Harmon in The Queen’s Gambit? That, and her drinking and her flamboyance and her misery and her endless performance as a character in her own drama: that she lacks (or can’t rely on) her authentic self is part of Katherine’s tragedy, but it also made her poor company, and Norah is similarly, if more quietly, histrionic.

Having said all that, the story of their relationship is ultimately moving: it requires empathy and forgiveness to love a mother like that, and by the novel’s end Norah has found her way to a version of her mother’s life story that gives priority to her best efforts, especially her care for her daughter—uneven, imperfect, but genuine. Early on Norah comments, “Did I already know that she was crazy? Just the way all mothers are crazy to their daughters, all mothers are wrong.” Most mothers probably feel the truth and the sting of that remark; Actress tells a story about moving past that alienating judgment to forgiveness and love.

I’m doing pretty well working my way through my Christmas book stack.

I’m doing pretty well working my way through my Christmas book stack.  The Gathering is also a very good novel–probably an excellent one. I feel much less inclined to urge you to read it if you haven’t already, though, because it is also a fairly lugubrious one. It is a family story of a particular kind: I want to say, of a particularly Irish kind, which may or may not be fair. Insofar as it has a plot, it is organized around the gathering (of course) of the remaining members of a large family (and assorted spouses and children) after the suicide of their brother Liam. It is narrated by his sister Veronica, and around this present gathering she weaves together a sad tapestry of memories and questions, at first mostly about her grandmother Ada and about Liam–who has never really been ‘right’ since they were first sent as children to stay with Ada-and eventually about what might be painful secrets in Veronica’s own past. If you suspect that the story’s original sin is sexual abuse, you are right, and how awful is it that this revelation not only does not come as a surprise in the novel but felt like a cliché? Enright’s treatment of it is not clichéd, or prurient, or sensational: it is sad and angry, and short on redemptive promises. She writes beautifully, and says a lot of things that will linger with me, like this bit, from early on before we know for sure why Veronica’s outlook is so shadowed:

The Gathering is also a very good novel–probably an excellent one. I feel much less inclined to urge you to read it if you haven’t already, though, because it is also a fairly lugubrious one. It is a family story of a particular kind: I want to say, of a particularly Irish kind, which may or may not be fair. Insofar as it has a plot, it is organized around the gathering (of course) of the remaining members of a large family (and assorted spouses and children) after the suicide of their brother Liam. It is narrated by his sister Veronica, and around this present gathering she weaves together a sad tapestry of memories and questions, at first mostly about her grandmother Ada and about Liam–who has never really been ‘right’ since they were first sent as children to stay with Ada-and eventually about what might be painful secrets in Veronica’s own past. If you suspect that the story’s original sin is sexual abuse, you are right, and how awful is it that this revelation not only does not come as a surprise in the novel but felt like a cliché? Enright’s treatment of it is not clichéd, or prurient, or sensational: it is sad and angry, and short on redemptive promises. She writes beautifully, and says a lot of things that will linger with me, like this bit, from early on before we know for sure why Veronica’s outlook is so shadowed:

My other recent reading (besides reading for my classes, of course) has been two pretty good mysteries. One was the first in Susie Steiner’s Manon Bradshaw series, Missing, Presumed, which I read out of order because when I first looked, only her most recent was locally available. The one I read then was good enough that I put this on my wish list, and I actually thought it was better in some ways–though that might because I already knew a bit about Manon. It was especially interesting to see how the family situation she’s in, in the later book, comes into being in this one. The other is the second of Dervla McTiernan’s series about Cormac Reilly (Ireland again!), The Scholar. This was very well done but–and this is very rare for me, suggesting I’m either a lazy or an inept reader of detective stories!–I more or less figured out the crime pretty early on. It didn’t matter that much to my enjoyment of the book, as I read crime fiction more for character and atmosphere than for the mystery itself.

My other recent reading (besides reading for my classes, of course) has been two pretty good mysteries. One was the first in Susie Steiner’s Manon Bradshaw series, Missing, Presumed, which I read out of order because when I first looked, only her most recent was locally available. The one I read then was good enough that I put this on my wish list, and I actually thought it was better in some ways–though that might because I already knew a bit about Manon. It was especially interesting to see how the family situation she’s in, in the later book, comes into being in this one. The other is the second of Dervla McTiernan’s series about Cormac Reilly (Ireland again!), The Scholar. This was very well done but–and this is very rare for me, suggesting I’m either a lazy or an inept reader of detective stories!–I more or less figured out the crime pretty early on. It didn’t matter that much to my enjoyment of the book, as I read crime fiction more for character and atmosphere than for the mystery itself.