A marriage, a birth, a death. This wasn’t a life. It was nothing like it. Life’s what happens in between. The tease of a flame at a dry twig. Snowflakes melting in upturned palms. The drip of chlorinated water from soaked curls, lips unsticking in a smile, outstretched arms with fingers crooked to coax a child into swimming. The dip of the tongue’s tip to the palm of the hand to lift a sweet blue pill from a skin-crease. These tiny things that change the world, minute by minute, and forever. These perishable moments, that are gone completely, if we don’t take the trouble of their telling.

I wish Jo Baker had not written Longbourn: if I hadn’t assumed that she was just one more unimaginative barnacle on the unstoppable ship Austen Always Sells, I might have read her other books sooner. Well, OK, I don’t wish that, since against all my expectations Longbourn, when I finally brought myself to read it, turned out to be really good. A Country Road, A Tree convinced me to try it; I went on to read The Undertow, also excellent—and now I can add that so too is The Telling.

The Telling is described on the cover as a “ghost story,” which would have put me off if Baker hadn’t already earned my trust. In fact, the blurb writers left out all the details that would have sold me the book: that it’s set in an old house called Reading Room Cottage, for example, named for an upstairs room featuring a massive built-in bookcase with an “archeological feel,” and that the historical story interwoven with its contemporary one is about the Chartists. In fact, it isn’t really a ghost story at all, at least not in a hokey haunted way. It’s more uncanny than supernatural, more about reverberations between past and present literalized as humming static in the air than about phantoms or visitations. The “ghost” sensed by Rachel, the modern-day protagonist, does have an identity, a story, one that Rachel eventually tries to uncover, only to be thwarted by the inadequacy of the archival record. We are the ones who know who Lizzy was and what happened to her in that house with the bookcase.

Lizzy’s presence in Rachel’s life — Rachel’s feeling that there’s someone else there and yet not there — does bring a frisson or chill into the novel. Baker’s as good at this kind of thing as Sarah Waters:

Lizzy’s presence in Rachel’s life — Rachel’s feeling that there’s someone else there and yet not there — does bring a frisson or chill into the novel. Baker’s as good at this kind of thing as Sarah Waters:

I felt it. A teetering, pregnant silence as if a breath had been drawn, and someone was about to speak. I looked up, glanced around the room. The daffodils on the windowsill, the grey paths across the floor, the silky ashes in the grate; it was all absolutely ordinary. The view from the window, grey sky and green fields. As I turned my head to look, I felt slow, as if moving through water. The air was thickening; if I lifted up a finger, and ran it through the air in front of me, it would leave a ripple. But it was too much to move a finger. I couldn’t move a finger. Each breath was a conscious effort.

Like Waters, Baker is smart enough to keep everything suggestive in this way: there’s no face looming through the window, no voice whispering in Rachel’s ear, no books shifting inexplicably about or lights mysteriously turning off or on. Everything abnormal thing Rachel (thinks she) feels could even be explained away by her unstable condition: she is recovering (barely) from depression brought on by the overlapping traumas of her mother’s death from cancer and the birth of her daughter. She has come to Reading Room Cottage to sort out her mother’s things and prepare the house for sale, and also to evade her husband’s loving but burdensome concern.

Lizzy, in her time, lives in the cottage with her parents. She is a housemaid; they are basket weavers and farmers struggling to sustain their family since the recent enclosure of some common land. To get by, they take in a lodger, a master carpenter who is also a radical—if, that it, it is radical to encourage working people to read, to question inequality, and to aspire to political representation. He’s the one who builds the shelves and stocks them with books which he begins leaving around for Lizzy to read. Until he came, she had “always read everything the way [she] was taught, as if it were gospel truth.” Fiction, to her, is an uncomfortable revelation: “I never knew that books could lie.” The books he lends her—Paradise Lost, Hamlet, The Odyssey, but also works of natural history and Lyell’s Principles of Geology—up-end Lizzy’s mental life, just as his presence, and the reading room he sets up for meetings and debates, disturb the already uneasy equilibrium in the community.

What brings Lizzy and Rachel together, across time (if we want to believe in ghosts) or just across the novel? Good as both strands were—both are convincing, gripping, moving—I was not 100% convinced that they made a unified whole. At any rate, the parallels between the two women’s stories were not obvious to me. What stands out most to me, thinking about them together, is that Rachel’s grief for her mother makes her acutely aware of how much of every life is ultimately lost. Lizzy’s sorrows are different; what draws her close to Rachel is not that their experiences are similar but that we don’t, or rather Rachel’s doesn’t, know anything about her. All that remains are fragile records, just as all that remains of Rachel’s mother are remnants already losing their meaning: “the photographs that Mum had selected, the moments of her life that she had wanted to keep, to return to, to experience again.” How different, too, is a memory from a haunting? Rachel’s mother is also now no more than an imagined presence. Stories are what remain. In a local bookstore, Rachel finds what we know are some of the books Lizzy read, and in its turn The Telling recreates and preserves the “perishable moments” of what Lizzy’s life might have been.

What brings Lizzy and Rachel together, across time (if we want to believe in ghosts) or just across the novel? Good as both strands were—both are convincing, gripping, moving—I was not 100% convinced that they made a unified whole. At any rate, the parallels between the two women’s stories were not obvious to me. What stands out most to me, thinking about them together, is that Rachel’s grief for her mother makes her acutely aware of how much of every life is ultimately lost. Lizzy’s sorrows are different; what draws her close to Rachel is not that their experiences are similar but that we don’t, or rather Rachel’s doesn’t, know anything about her. All that remains are fragile records, just as all that remains of Rachel’s mother are remnants already losing their meaning: “the photographs that Mum had selected, the moments of her life that she had wanted to keep, to return to, to experience again.” How different, too, is a memory from a haunting? Rachel’s mother is also now no more than an imagined presence. Stories are what remain. In a local bookstore, Rachel finds what we know are some of the books Lizzy read, and in its turn The Telling recreates and preserves the “perishable moments” of what Lizzy’s life might have been.

Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil.

Elizabeth’s departure, once the rain had stopped, caused no particular trouble to anyone below stairs. She just put on her walking shoes and buttoned up her good spencer, threw a cape over it all, and grabbed an umbrella just in case the rain came on again. Such self-sufficiency was to be valued in a person, but seeing her set off down the track, and then climb the stile, Sarah could not help but think that those stockings would be perfectly ruined, and that petticoat would never be the same again, no matter how long she soaked it. You just could not get mud out of pink Persian. Silk was too delicate a cloth to boil. Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. (

Jo Baker’s Longbourn would be a pretty tedious novel if all it did was highlight or criticize these aspects of Austen’s “light, bright, and sparkling” original, and (to me at least) it would also be a boring one if all it did was tell the same story as Pride and Prejudice from a different point of view. I had avoided reading Longbourn up to now because I was so sure it would fall into at least one of these traps, or just be bad by comparison, as so many novels “inspired” by great novels are. ( I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its

I’m undecided about that (and I’d be curious to know what other people think). Certainly some of Longbourn‘s appeal comes from its engagement with its  But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her.

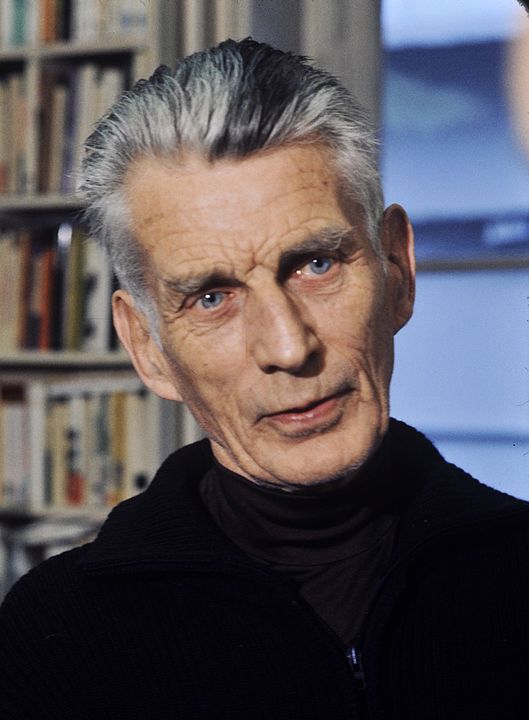

But Baker isn’t rewriting Pride and Prejudice, which carries on cheerfully, and more or less exactly as Austen wrote it, even as Baker’s own drama plays out. She adds some pieces to it: the most important one is Mr. Bennet’s early dalliance which resulted in the living son he and Mrs. Bennet never have (thus the whole rest of Austen’s plot!). I wasn’t convinced that this storyline really fit Mr. Bennet, but I liked the way the presence of this illegitimate heir added to Austen’s critique of the laws of inheritance: it highlights a different kind of injustice from the one the Bennet sisters face. (Some of the plot points around this son struck me as a bit too pat, but the section about his wartime experiences is really well done—gripping, even harrowing, in a most un-Austen-like way.) I particularly liked the way Baker used Wickham: everything about his role in her story seemed entirely in keeping with the man we know from Austen’s. Mostly, though, Austen’s characters are peripheral in Baker’s novel, which I thought was really smart. It gives Baker room to develop her own interesting characters, to set her own vivid scenes—in short, to write her own good novel, without relying on Austen to win the game for her. My near total first-hand ignorance of Samuel Beckett’s work would probably be a real advantage to me in David Lodge’s famous game ‘Humiliation.’ Even my second-hand knowledge is pretty limited: I have a casual idea of what Waiting for Godot is like and about, and that’s it. As with all novels steeped in another author’s lives and ideas, Jo Baker’s A Country Road, A Tree is probably better appreciated by someone else, then, someone who can do more than stumble over a reference to an ‘endgame’ and think “hey, that’s probably

My near total first-hand ignorance of Samuel Beckett’s work would probably be a real advantage to me in David Lodge’s famous game ‘Humiliation.’ Even my second-hand knowledge is pretty limited: I have a casual idea of what Waiting for Godot is like and about, and that’s it. As with all novels steeped in another author’s lives and ideas, Jo Baker’s A Country Road, A Tree is probably better appreciated by someone else, then, someone who can do more than stumble over a reference to an ‘endgame’ and think “hey, that’s probably  The specific scenes that need setting are those of Beckett’s years in occupied France, during which he played a part (a small part, he insisted) in the French Resistance. I didn’t know that this was part of Beckett’s story. Anyone’s experience of this kind would make a compelling novel (and of course there have been many other books of one kind or another about this period), and Baker does a really good job conveying the anxiety of it all: it’s an extremely tense narrative, especially from the first moment Beckett joins in with the resistance efforts. The vicarious pressure of living in constant fear of exposure or betrayal, and then with the immediate hazards of escape and living in hiding, was almost too much to add to my own currently high levels of anxiety as the third COVID wave hits Halifax and once again everyday activities feel fraught with risk. In fact, a lot about A Country Road, A Tree felt timely, as something Baker’s Beckett is particularly attuned to is the disorientation induced by the ways crisis defamiliarizes even our most routine activities and intimate spaces.

The specific scenes that need setting are those of Beckett’s years in occupied France, during which he played a part (a small part, he insisted) in the French Resistance. I didn’t know that this was part of Beckett’s story. Anyone’s experience of this kind would make a compelling novel (and of course there have been many other books of one kind or another about this period), and Baker does a really good job conveying the anxiety of it all: it’s an extremely tense narrative, especially from the first moment Beckett joins in with the resistance efforts. The vicarious pressure of living in constant fear of exposure or betrayal, and then with the immediate hazards of escape and living in hiding, was almost too much to add to my own currently high levels of anxiety as the third COVID wave hits Halifax and once again everyday activities feel fraught with risk. In fact, a lot about A Country Road, A Tree felt timely, as something Baker’s Beckett is particularly attuned to is the disorientation induced by the ways crisis defamiliarizes even our most routine activities and intimate spaces.  Following Beckett’s own lead, Baker never glamorizes Beckett’s resistance work; she doesn’t even treat it as particularly heroic. It’s true that, in retrospect at least, he came through it all pretty well, better than many of his collaborators in these efforts not to mention many, many other people. In the end what’s interesting and important about this particular story about that time and that work is what it meant to Beckett as a writer: that’s really what A Country Road, A Tree is about. Does that trivialize the war, the resistance, the deaths and suffering? I don’t think so. Beckett did more than many of us would to push back against evil, but that wasn’t his chosen work, and it seems right to pay attention to what he made of that experience, or what that experience meant to him, when its imperatives lifted and he was once again able to create unimpeded–or, at any rate, unimpeded by quite the same array of external crises. We shouldn’t let war (or COVID) convince us that things not obviously or directly related to them are not important, that the right response is to marginalize or pare away things we genuinely value. Apparently Churchill’s line about preserving the arts (“then what are we fighting for?”) is apocryphal, something he never said, but the sentiment it expresses is surely true, or at least a lot of us agree with it. To think that Beckett’s writing is less important than his efforts against the Nazis is, in a way, to lose the war. (I have questions like this about what really matters during a crisis in mind because it’s part of what I decided to write about in the essay I’ve been working on about The Balkan Trilogy—out soon, I hope.)

Following Beckett’s own lead, Baker never glamorizes Beckett’s resistance work; she doesn’t even treat it as particularly heroic. It’s true that, in retrospect at least, he came through it all pretty well, better than many of his collaborators in these efforts not to mention many, many other people. In the end what’s interesting and important about this particular story about that time and that work is what it meant to Beckett as a writer: that’s really what A Country Road, A Tree is about. Does that trivialize the war, the resistance, the deaths and suffering? I don’t think so. Beckett did more than many of us would to push back against evil, but that wasn’t his chosen work, and it seems right to pay attention to what he made of that experience, or what that experience meant to him, when its imperatives lifted and he was once again able to create unimpeded–or, at any rate, unimpeded by quite the same array of external crises. We shouldn’t let war (or COVID) convince us that things not obviously or directly related to them are not important, that the right response is to marginalize or pare away things we genuinely value. Apparently Churchill’s line about preserving the arts (“then what are we fighting for?”) is apocryphal, something he never said, but the sentiment it expresses is surely true, or at least a lot of us agree with it. To think that Beckett’s writing is less important than his efforts against the Nazis is, in a way, to lose the war. (I have questions like this about what really matters during a crisis in mind because it’s part of what I decided to write about in the essay I’ve been working on about The Balkan Trilogy—out soon, I hope.)  And it is probably in this case best, anyway, not to consider these things as in opposition. Writers’ experiences become their art, and that’s what Baker is primarily exploring: how being alone and afraid and constantly confronted with irrationality and violence and threats both literal and existential brought Beckett to an understanding of what he wanted to write and how.

And it is probably in this case best, anyway, not to consider these things as in opposition. Writers’ experiences become their art, and that’s what Baker is primarily exploring: how being alone and afraid and constantly confronted with irrationality and violence and threats both literal and existential brought Beckett to an understanding of what he wanted to write and how.