After college, for a period of two years and eight months, the “real world” became a room at Beth Israel Hospital and Tom’s one-bedroom apartment in Queens. Never mind that I was starting out at a glamorous job in a midtown skyscraper; it was these quieter spaces that taught me about beauty, grace, and loss—and, I suspected, about the meaning of art.

When in June of 2008, Tom died, I applied for the most straightforward job I could think of in the most beautiful place I knew. This time, I arrive at the Met with no thought of moving forward. My heart is full, my heart is breaking, and I badly want to stand still awhile.

The “glamorous job” Patrick Bringley turned his back on was at the New Yorker; the job he took after his brother Tom’s death was as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a job he held for a decade. Reading All the Beauty in the World, his moving, meditative, wide-ranging reflections on his experience standing for thousands of hours among some of the world’s greatest treasures, I wondered if he always had it in the back of his mind that there would be a book in it someday. It’s hard to imagine anyone both literary and ambitious enough to work at the New Yorker not having that thought! This was not in any way a cynical notion on my part; if anything, I feel lucky that, with whatever long-term intentions, Bringley clearly thought and wrote down enough during his time in the museum that I could now read about it and be guided by him towards insights into what art can mean and do for us if we just stand still long enough to let it.

One of Bringley’s central insights is that art’s power comes from what it shows us about the most commonplace, and thus most human, parts of life. “Much of the greatest art,” he observes,

seeks to remind us of the obvious. This is real, is all it says. Take the time to stop and imagine more fully the things you already know. Today my apprehension of the awesome reality of suffering might be as crisp and clear as Daddi’s great painting.* But we forget these things. They become less vivid. We have to return as we do to paintings, and face them again.

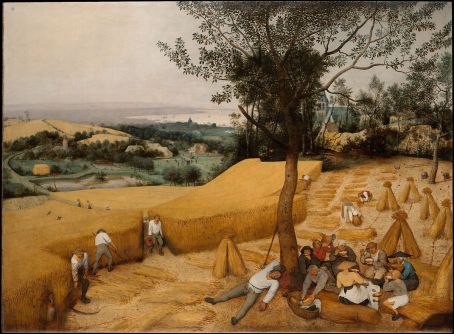

It isn’t always suffering and death that art invites us to stand and face. One of Bringley’s favorite paintings is Pieter Bruegel’s The Harvesters, which shows, in the foreground, a little group of peasants on their lunch break:

Looking at Bruegel’s masterpiece I sometimes think: here is a painting of literally the most common thing on earth. Most people have been farmers. Most of these have been peasants. Most lives have been labor and hardship punctuated by rest and the enjoyment of others. It is a scene that must have been so familiar to Pieter Bruegel it took an effort to notice it. But he did notice it. And he situated this little, sacred, ragtag group at the fore of his vast, outspreading world.

“I am sometimes not sure,” Bringley adds, “which is the more remarkable: that life lives up to great paintings, or that great paintings live up to life.”

The individual sections of All the Beauty in the World are organized, more or less, around Bringley’s assignments to particular rooms or wings or exhibits; the larger framing is his gradual reconciliation, if that’s the right word, with the “real world” outside the museum as he learns to live with Tom’s loss. Both the people he works with (who come from all parts of the world and all have their own stories about how they came to be standing guard over Van Gogh’s Irises or the tomb of Perneb) and the people he encounters as visitors all play a part in this emotional journey, but it is the art that matters the most, in ways that are better suited to samples than summaries. Here, for instance, is Bringley’s description of a silk scroll hand-painted by Guo Xi, a “Northern Song Dynasty” master:

The individual sections of All the Beauty in the World are organized, more or less, around Bringley’s assignments to particular rooms or wings or exhibits; the larger framing is his gradual reconciliation, if that’s the right word, with the “real world” outside the museum as he learns to live with Tom’s loss. Both the people he works with (who come from all parts of the world and all have their own stories about how they came to be standing guard over Van Gogh’s Irises or the tomb of Perneb) and the people he encounters as visitors all play a part in this emotional journey, but it is the art that matters the most, in ways that are better suited to samples than summaries. Here, for instance, is Bringley’s description of a silk scroll hand-painted by Guo Xi, a “Northern Song Dynasty” master:

Ink on silk is an unforgiving medium; there are no do-overs; he couldn’t rub out and paint over his mistakes as the old masters could do with oils. My eyes can trace every stroke Guo made in AD 1080. No part of his artistry is hidden from me, nothing submerged under overlapping layers. According to Guo’s son, the master’s regular practice was to meditate several hours, then wash his hands and execute a painting as if with a single sweep of his arm . . . What this picture has afforded for a thousand years it affords today. My eyes travel the same old routes, past the fishermen in their small, still boats, the bare autumnal trees, the peddlers and their pack mule, the rock croppings, the stooped old men ascending a hill, and into the mountains shrouded in mist. It is achingly beautiful . . . I am happy to be inside this picture, so clearly a melding of nature and the artist’s mind. Guo himself feels like my intimate . . .

Here he is being won over, after long skepticism about the Impressionists, to the magic of Monet’s Vétheuil in Summer:

I see a village and a river and the village’s reflection suspended in river water, only in Monet’s world there is no such thing as sunlight really, just color. Monet has spread around the sunlight color, like the goodly maker of his little universe. He has spread it, splashed it, and affixed it to the canvas with such mastery that I can’t put an end to its ceaseless shimmering. I look at the picture a long time, and it only grows more abundant; it won’t conclude.

Monet, I realize, has painted that aspect of the world that can’t be domesticated by vision—what Emerson called the “flash and sparkle” of it, in this case a million dappled reflections rocking and melting in the waves . . . Monet’s picture brings to mind one of those rarer moments where every particle of what we apprehend matters—the breeze matters, the chirping of birds matters, the nonsense a child babbles matters—and you can adore the wholeness, or even the holiness, of that moment.

With regret, I have left out some parts of this passage, because it is quite long, but I loved every word of it. One more, from Bringley’s encounter with a “nkisi, or power figure, made by the Songye people of what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo”:

Above all, I can see the extraordinary geometry the wood-carver achieved in his effort to make the nkisi supernatural. This artist faced a tremendous formal challenge, I realize. Unlike Guo’s scroll or Monet’s painting, his sculpture wasn’t an imitation or a depiction of anything else. It wasn’t meant to look like a divine being; it was the divine being and, as such, had to appear as though it existed across a chasm from ordinary human efforts. It had to look a bit like a newborn baby looks . . . a new, miraculous, self-insistent whole.

. . . More than just dazzled, I am moved. With its eyes softly shut, the nkisi has a powerful air of inwardness, as though summoning the will to take on perilous forces closing in on it . . . it had to be this magnificent to push back.

There is much more, ranging across the breadth of the museum’s collections. Although I learned a lot from Bringley’s explanations of specific artefacts, they are (almost) beside the point, as these examples show: the interest and impact of the book comes mostly from his personal interactions—emotional and intellectual—with the works of art. It is an idiosyncratic kind of art appreciation, perhaps, though well-informed (he has done his research, in and out of the museum) and open-minded, but I think Bringley would argue that this is also the best kind.

As the years pass, all this time spend standing still gradually brings Bringley back in touch with the movement of life itself. “Grief,” he aptly observes,

is among other things a loss of rhythm. You lose someone, it puts a hole in your life and for a time you huddle down in that hole. In coming to the Met, I saw an opportunity to conflate my hole with a grand cathedral, to linger in a place that seemed untouched by the rhythms of the everyday. But those rhythms have found me again, and their invitations are alluring. It turns out I don’t wish to stay quiet and lonesome forever.

One sign of his revitalization is, paradoxically, that art begins to lose its hold on him. Looking at a painting of a mother and child by Mary Cassatt, he is overcome with its beauty: “for the first time in a long time, I simply adore.” He is saddened by his realization that this total absorption in a work of art has become less frequent for him:

Strangely, I think I am grieving for the end of my acute grief. The loss that made a hole at the center of my life is less on my mind than sundry concerns that have filled the hole in. And I suppose that is right and natural, but it’s hard to accept.”

All grievers probably recognize this reluctance to admit that time simply will not stand still with you and your sorrow (I’m reminded yet again of Denise Riley—”The dead slip away, as we realize that we have unwillingly left them behind us in their timelessness—this second, now final, loss”). Life is movement, and most of us step back into the current again at some point, changed but persisting. “Sometimes,” Bringley concludes,

life can be about simplicity and stillness, in the vein of a watchful guard amid shimmering works of art. But it is also about the head-down work of living and struggling and growing and creating.

And so he leaves this job too. From now on when he returns to the museum it will be as a visitor, just another person stepping inside for a moment to be reminded of the obvious, and to be reassured

And so he leaves this job too. From now on when he returns to the museum it will be as a visitor, just another person stepping inside for a moment to be reminded of the obvious, and to be reassured

that some things aren’t transitory at all but rather remain beautiful, true, majestic, sad, or joyful over many lifetimes—and here is the proof, painted in oils, carved in marble, stitched into quilts.

How I wish I could walk out the door right now and take him up on his closing advice about the best time to visit (“come in the morning . . . when the museum is quietest”). I used to visit the Met regularly myself: as a graduate student at Cornell, I took advantage of my (relative) proximity to the city to get season tickets to the Metropolitan Opera (a dream come true for a long-time listener to their Saturday afternoon broadcasts) and as often as I could, I worked in a museum visit as well. There is never enough time to take in everything you want to see—Bringley had a decade, thousands of hours, and will still be going back, after all! I often feel, in art galleries, that I never know enough to get the most out of them, but Bringley has not just inspired me but given me new confidence. “You’re qualified to weigh in on the biggest questions artworks raise,” he says in his closing peroration:

So under the cover of no one hearing your thoughts, think brave thoughts, searching thoughts, painful thoughts, and maybe foolish thoughts, not to arrive at right answers but to better understand the human mind and heart as you put both to use.

I like that idea of how to be in a museum—and I loved this book.

*You can find links to all the works Bringley references here. Some of them, for copyright reasons, can’t be downloaded, which is why my inserted images (all public domain) don’t 100% correspond to the examples I’ve quoted from the book.

Everything goes back to normal. Peter Manuel becomes a scary story people tell each other. Just a story. Just a creepy story about a serial killer.

Everything goes back to normal. Peter Manuel becomes a scary story people tell each other. Just a story. Just a creepy story about a serial killer.

One reason that to date I have not pursued this idea is that true crime, as a genre, makes me uneasy, squeamish, even—ethically, but also more literally. My experience with it is limited and mostly from television, where, for example, I have watched both the TV serial and the documentary The Staircase, as well as both The People vs O. J. Simpson and O. J.: Made in America — and also one season of Netflix’s Making a Murderer. If you can criticize made-up crime fiction for treating imaginary violent deaths as good subjects for an evening’s entertainment, how much worse is it to take the suffering and brutality and tragedy of actual murders and engage us with it in the spirit of a whodunit? Obviously, in both cases everything depends on the treatment: plenty of detective fiction does a lot more than offer us a puzzle, and I’m sure it is possible for true crime writing (or podcasting or dramatizations) to avoid the pitfalls of sensationalism, speculation, and grisly voyeurism. But it can’t help but be a grim kind of reading, writing, watching or thinking, and for my own forays into the already unhappy territory of murder I have just always relied, however naively, on the insulation that seemed to be provided, morally and imaginatively, by knowing that none of what I was reading about ever actually happened to anyone real.

One reason that to date I have not pursued this idea is that true crime, as a genre, makes me uneasy, squeamish, even—ethically, but also more literally. My experience with it is limited and mostly from television, where, for example, I have watched both the TV serial and the documentary The Staircase, as well as both The People vs O. J. Simpson and O. J.: Made in America — and also one season of Netflix’s Making a Murderer. If you can criticize made-up crime fiction for treating imaginary violent deaths as good subjects for an evening’s entertainment, how much worse is it to take the suffering and brutality and tragedy of actual murders and engage us with it in the spirit of a whodunit? Obviously, in both cases everything depends on the treatment: plenty of detective fiction does a lot more than offer us a puzzle, and I’m sure it is possible for true crime writing (or podcasting or dramatizations) to avoid the pitfalls of sensationalism, speculation, and grisly voyeurism. But it can’t help but be a grim kind of reading, writing, watching or thinking, and for my own forays into the already unhappy territory of murder I have just always relied, however naively, on the insulation that seemed to be provided, morally and imaginatively, by knowing that none of what I was reading about ever actually happened to anyone real.

Mina talks in the interview about people’s fascination with serial killers (a point that reminds me of another ‘true crime’ series I’ve seen, “Mindhunter”—which itself walks a fine line in its treatment of its subjects) and notes that people usually want to see them as anomalous. The version of Manuel that her book gives us is hardly “normal,” but at the same time there’s something small, petty, even pathetic about him, rather than monstrous. He represents himself at the trial and one factor in his favor, we’re told, is that

Mina talks in the interview about people’s fascination with serial killers (a point that reminds me of another ‘true crime’ series I’ve seen, “Mindhunter”—which itself walks a fine line in its treatment of its subjects) and notes that people usually want to see them as anomalous. The version of Manuel that her book gives us is hardly “normal,” but at the same time there’s something small, petty, even pathetic about him, rather than monstrous. He represents himself at the trial and one factor in his favor, we’re told, is that

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place.

The best of them was undoubtedly Herbert Clyde Lewis’s Gentleman Overboard, which I was inspired to read by listening to Trevor and Paul talk about it on the Mookse and the Gripes podcast. It is a slim little book with a simple little story, but it contains vast depths of insight and feeling, and even some touches of humor, as it follows Henry Preston Standish overboard into the Pacific Ocean and then through the many hours he spends floating and treading water and hoping not to drown before the ship he had been traveling on comes back to pick him up. We also get to see how the folks on board react when he’s discovered to be missing, and we follow his thoughts and memories, learning more about him and how he came to be where he is—not in the ocean, which is easily and bathetically explained (he slips on a spot of grease at just the wrong moment when he’s in just the wrong place), but sailing from Honolulu to Panama in the first place. I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite:

I also really appreciated Molly Peacock’s A Friend Sails in on a Poem, which is an account of her long personal and working friendship with fellow poet Phillis Levin. It is a blend of memoir and craft book, which might not work for every reader, but I found the insider perspective on how poems are created and shaped fascinating and illuminating. Peacock includes some of the poems that she talks about; this was my favorite: I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer.

I was more ambivalent about Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. At times I found its fragmentary structure annoying in the way I often feel about books that read to me as unfinished, deliberately or not. But I also thought some of the rhetorical devices Smith uses to structure it were very effective, especially her reflections on the questions, usually well-meaning, people have asked her about the breakdown of her marriage, her divorce, and her writing about it: there are the answers she would like to give, typically raw, fraught, and conflicted, reflecting the complexity of her feelings and experiences, which defy straightforward replies; and then there are the answers she does give, neater, shorter, sanitized. That rang true to me, as it probably does to anyone who has been through something difficult and knows that when people ask how you are doing, they are not really, or are only rarely, asking for the real answer. Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his

Finally, I just finished Mick Herron’s London Rules, the third (or possibly fourth?) of his  I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps

I hope to get back to more regular blogging about books, and about my classes, an exercise in self-reflection that I’ve missed. It has been a very busy and often stressful couple of months, for personal reasons (about which, as I have said before, more eventually, perhaps), but whenever I do settle in to write here I am reminded of how good it feels, of how much I enjoy the both the freedom to say what I think and the process of figuring out what that is! My current reading (slowly, in the spirit of Kim and Rebecca’s #KateBriggs24 read-along, though I am not an official participant) is Kate Brigg’s The Long Form, which I am enjoying a lot; I’m experimenting with having more than one book on the go, as well, so now that I’ve finished London Rules I will go back to my tempting stack of library books and pick another to contrast with Briggs, perhaps

To anyone familiar with the rigid strictures women faced in the 19th-century, some aspects of Fayne will be predictable, even with the device of an intersex character to subvert the binaries they were based on. Fayne succeeds because MacDonald is a fine storyteller who has more to say than “the times were unfair to women,” or maybe more accurately more she wants to do than just offer this critique (which is not to say it’s not an important critique, or that through the character of Charles / Charlotte she doesn’t extend it significantly). Everything about Fayne suggests that MacDonald wants to have fun as a novelist by writing an unabashedly melodramatic novel with her own variations on the kinds of twists and surprises we get in Gothic or sensation fiction: mistaken or secret identities, false confinements, drugs, sexual secrets, lost heirs, treachery and deceptions of all kinds—but also true-hearted friends and allies pointing the way towards solutions to these mysteries and towards a future in which the people we come to care for will be safe and happy. Overall, it works! It is fun, gripping, surprising, infuriating, and often touching. And, not incidentally, Charlotte herself is a fine addition to the list of 19th-century literary heroines who put up lively resistance to oppressive norms: Jane Eyre, Maggie Tulliver, and Marion Halcombe, for starters. There are many moments in Fayne that are clearly nods to Charlotte’s rebellious predecessors.

To anyone familiar with the rigid strictures women faced in the 19th-century, some aspects of Fayne will be predictable, even with the device of an intersex character to subvert the binaries they were based on. Fayne succeeds because MacDonald is a fine storyteller who has more to say than “the times were unfair to women,” or maybe more accurately more she wants to do than just offer this critique (which is not to say it’s not an important critique, or that through the character of Charles / Charlotte she doesn’t extend it significantly). Everything about Fayne suggests that MacDonald wants to have fun as a novelist by writing an unabashedly melodramatic novel with her own variations on the kinds of twists and surprises we get in Gothic or sensation fiction: mistaken or secret identities, false confinements, drugs, sexual secrets, lost heirs, treachery and deceptions of all kinds—but also true-hearted friends and allies pointing the way towards solutions to these mysteries and towards a future in which the people we come to care for will be safe and happy. Overall, it works! It is fun, gripping, surprising, infuriating, and often touching. And, not incidentally, Charlotte herself is a fine addition to the list of 19th-century literary heroines who put up lively resistance to oppressive norms: Jane Eyre, Maggie Tulliver, and Marion Halcombe, for starters. There are many moments in Fayne that are clearly nods to Charlotte’s rebellious predecessors.

Orbital does more, though, than indulge in this potentially saccharine vision of a perfect world spoiled, pointlessly, by human squabbles, greed, and violence. This is a common starting point, the novel proposes, including for the astronauts, initially overwhelmed by the invisibility of the borders and boundaries that motivate so much hostility and cause so much death:

Orbital does more, though, than indulge in this potentially saccharine vision of a perfect world spoiled, pointlessly, by human squabbles, greed, and violence. This is a common starting point, the novel proposes, including for the astronauts, initially overwhelmed by the invisibility of the borders and boundaries that motivate so much hostility and cause so much death: The astronauts are also aware that their own astonishing vantage point is itself implicated in these forces; running through the novel is a debate, unsettled (perhaps impossible to settle), about the value of space exploration, about ideas of progress and the capacity of human invention to do as much harm as good. One of the astronauts, Chie, reflects on her own family history, including the accidents of circumstance that meant her grandfather and her mother survived the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. What story did her mother intend Chie to discern in the photograph she has given her labelled “Moon Landing Day”?

The astronauts are also aware that their own astonishing vantage point is itself implicated in these forces; running through the novel is a debate, unsettled (perhaps impossible to settle), about the value of space exploration, about ideas of progress and the capacity of human invention to do as much harm as good. One of the astronauts, Chie, reflects on her own family history, including the accidents of circumstance that meant her grandfather and her mother survived the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. What story did her mother intend Chie to discern in the photograph she has given her labelled “Moon Landing Day”? The last two months of 2023 have been so frantic (about which more, perhaps, some other time) that not only did I get very little reading done that wasn’t absolutely necessary for work, but the chaotic atmosphere drove almost all recollection of what I’d read or written earlier in the year clear out of my mind. It’s a good thing I keep records! Looking them over, it was nice to be reminded of what was actually a pretty good year for both reading and writing. I’ll run through the highlights (and also some lowlights) here, as has been my year-end ritual since I started Novel Readings in 2007.

The last two months of 2023 have been so frantic (about which more, perhaps, some other time) that not only did I get very little reading done that wasn’t absolutely necessary for work, but the chaotic atmosphere drove almost all recollection of what I’d read or written earlier in the year clear out of my mind. It’s a good thing I keep records! Looking them over, it was nice to be reminded of what was actually a pretty good year for both reading and writing. I’ll run through the highlights (and also some lowlights) here, as has been my year-end ritual since I started Novel Readings in 2007. When I was asked by Trevor and Paul at the wonderful Mookse & Gripes podcast to contribute to their “best of the year” round-up episode, the book that immediately came to mind for me was John Cotter’s memoir Losing Music. It deserved but didn’t get a blog post of its own, but you can read a bit about it

When I was asked by Trevor and Paul at the wonderful Mookse & Gripes podcast to contribute to their “best of the year” round-up episode, the book that immediately came to mind for me was John Cotter’s memoir Losing Music. It deserved but didn’t get a blog post of its own, but you can read a bit about it  A stretch of uninspiring reading early in the year was broken by Jessica Au’s

A stretch of uninspiring reading early in the year was broken by Jessica Au’s  Barbara Kingsolver’s

Barbara Kingsolver’s  I can’t say reading

I can’t say reading  I wrote three reviews for the TLS in 2023, Toby Litt’s

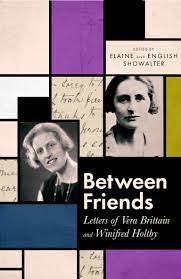

I wrote three reviews for the TLS in 2023, Toby Litt’s  I wrote two other somewhat more academic pieces, though neither of them was, strictly speaking, a “research” publication. One was a review for Women’s Studies of Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby’s correspondence in an excellent new edition by Elaine and English Showalter; the other was an essay for a forum organized by my friend and (nearby) colleague Tom Ue on ‘teaching the Victorians’ today, which is coming out eventually in the Victorian Review. I have written literally thousands of words about how I teach the Victorians today: this was a task for which almost two decades of blogging was exactly the right preparation!

I wrote two other somewhat more academic pieces, though neither of them was, strictly speaking, a “research” publication. One was a review for Women’s Studies of Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby’s correspondence in an excellent new edition by Elaine and English Showalter; the other was an essay for a forum organized by my friend and (nearby) colleague Tom Ue on ‘teaching the Victorians’ today, which is coming out eventually in the Victorian Review. I have written literally thousands of words about how I teach the Victorians today: this was a task for which almost two decades of blogging was exactly the right preparation!

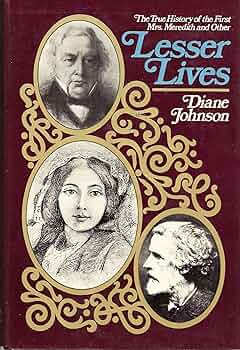

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says,

That’s the book I expected The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith to be: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith’s life story, with Mary Ellen herself placed, rightly, at its center. And that is what we get, sort of, in part. Usually what is known about Mary Ellen is what the figure Johnson calls “the Biographer” has said about her in passing, while telling the story of her famous second husband. “But of course,” as Johnson says, And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.”

And yet, Johnson considers, or imagines Mary Ellen’s contemporaries considering, her upbringing may have taught her to want things and to behave in ways incompatible with ordinary expectations for nice young ladies of the time. Johnson gives a brisk and basically sound overview of 19th-century gender roles and conventions, familiar to anyone who has read around in or about the history and literature of the period; she also rightly notes that the “ideal” woman (“innocent, unlearned, motherly”) was always a fiction, “encountered more often in the breach than in the observance,” although her image exerted powerful influence over how real women’s behavior was judged, as Mary Ellen’s history (meaning not her life, but the way that life would be told) was to show. Peacock’s good intentions may, ironically, have set Mary Ellen up for failure: “perhaps Mary Ellen Peacock would have been better off if she had not been so clever and educated.” There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later

There is a lot about how things then unfolded that Johnson (like her antagonist “the Biographer”) can’t know for sure. The crucial undisputed fact is that Mary Ellen left Meredith, “eloping” with their mutual friend, the artist—and later  The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write.

The surprising thing about The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, for me, was how much else it does besides reconstitute Mary Ellen’s biography. One fascinating aspect is Johnson’s self-consciousness about her own methodology, something that becomes explicit through her extensive notes. These turn out to be only incidentally about citing sources. A lot of them amplify or illustrate parts of the main text (for example, in the notes you will find many of the recipes associated with the cookery books by Mary Ellen or her daughter by her first marriage, Edith Nicolls). But others take on complex questions about how to do the work Johnson has undertaken, and particularly about how to understand the relationship between conventional biographical sources and information and the insights that are offered by an author’s writings, specifically in this case by Meredith’s novels. This is, as Johnson is clearly aware, a vexed issue: she raises the specter of what critics call the “biographical fallacy,” which can lead to “facile connections” between the life and the art, but also of the biographical tendency to chronicle the work “without imagining that there was much connection between that work and the writer’s ongoing life experiences.” She advocates what she calls, citing Frederick Crews, “a sense of historical dynamics,” recognizing that though a one-to-one correspondence is an implausible assumption, still there inevitably relationships between writers’ lives and what they write. I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas,

I actually found more powerful, though (perhaps, again, because this particular polemic has lost some of its urgency, though certainly not all of it), the sections of The True History that remind us that, from the right perspective, all lives are lesser. At these times Johnson’s book is less a literary history or biography and more a quirky form of momento mori, its attention to the leveling effects of death and time serving to puncture even the most inflated vanity even as it offers (perhaps) some philosophical consolation. “Whether Felix grew up to be like his Mama, or his Grandpapa, or his Papa,” she observes, in a passage characteristic of the book’s engaging yet disorienting blend of briskness and gravitas, I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by

I recommended this book for my book club as a “feminist palate cleanser” after Money. (I was also inspired by  Money, money, money,

Money, money, money, But it matters (to me, at least) what those sentences are about, and also what they are for, and for me and most of the others in my book club, this was really the sticking point. What is it exactly that we are being invited to participate in when we read this novel? How far does “it’s for comic effect” excuse offering up the things Self says and does for our (presumed) entertainment? What kind of implied author (to let Amis himself temporarily off the hook) thinks that we will laugh, not just at how stupid Self is at the opera but at his attempts at rape? that we will be engaged and rewarded by a monologue that (however energetic and rhetorically ingenious) is relentlessly sexist and racist and bigoted? Again, we get it: John Self is an anti-hero, mercilessly exposed in all his vices; the novel is satirical, Rabelaisian, Swiftian, pick your poison. It is poisonous stuff, though, and—to bring Amis back into it—there’s such a sense of gleeful bad boy “look at me” about the whole thing, with all the metafictional cleverness deployed as back-up in case the whole “I’m only joking” excuse isn’t enough. That it is such a popular book among (as far we could tell, only) male readers is disconcerting: it’s as if an uncomfortable number of them enjoy a chance to vicariously indulge the kinds of demeaning, exploitative, offensive attitudes (towards women especially) that they know better than to express in propria persona. As we discussed, we have all had the tediously unpleasant experience, at one point of another, of calling out sexism in conversation with men we know, or in TV or movies we are watching with them, only to be dismissed or shut down or worse—often, again, with “it’s only a joke.” The feminist kill-joy is a role we’d rather not have to play, but the alternative is to shut up and take it. Between us, too, we’ve had enough of the other kinds of bad experiences John Self inflicts on the women in his life not to find his shamelessness about them entertaining. We don’t need any lessons in how bad this kind of s–t is, after all, so what social or moral or other revelation can possibly come our way from approaching them by way of John Self?

But it matters (to me, at least) what those sentences are about, and also what they are for, and for me and most of the others in my book club, this was really the sticking point. What is it exactly that we are being invited to participate in when we read this novel? How far does “it’s for comic effect” excuse offering up the things Self says and does for our (presumed) entertainment? What kind of implied author (to let Amis himself temporarily off the hook) thinks that we will laugh, not just at how stupid Self is at the opera but at his attempts at rape? that we will be engaged and rewarded by a monologue that (however energetic and rhetorically ingenious) is relentlessly sexist and racist and bigoted? Again, we get it: John Self is an anti-hero, mercilessly exposed in all his vices; the novel is satirical, Rabelaisian, Swiftian, pick your poison. It is poisonous stuff, though, and—to bring Amis back into it—there’s such a sense of gleeful bad boy “look at me” about the whole thing, with all the metafictional cleverness deployed as back-up in case the whole “I’m only joking” excuse isn’t enough. That it is such a popular book among (as far we could tell, only) male readers is disconcerting: it’s as if an uncomfortable number of them enjoy a chance to vicariously indulge the kinds of demeaning, exploitative, offensive attitudes (towards women especially) that they know better than to express in propria persona. As we discussed, we have all had the tediously unpleasant experience, at one point of another, of calling out sexism in conversation with men we know, or in TV or movies we are watching with them, only to be dismissed or shut down or worse—often, again, with “it’s only a joke.” The feminist kill-joy is a role we’d rather not have to play, but the alternative is to shut up and take it. Between us, too, we’ve had enough of the other kinds of bad experiences John Self inflicts on the women in his life not to find his shamelessness about them entertaining. We don’t need any lessons in how bad this kind of s–t is, after all, so what social or moral or other revelation can possibly come our way from approaching them by way of John Self? Our discussion wasn’t all negative. One member of the group noted that she felt John Self was a genuinely memorable, even iconic character, and we all grudgingly agreed that, hate him though we did, he was brilliantly executed: his voice (which is what Amis identified as the most important aspect of the novel, and fair enough) is distinctive and unforgettable. That we would like to forget it could, I suppose, be considered our problem, not the novel’s! Money also prompted a lot of discussion about the more general question of how far a novelist can or should go with an offensive character; we also considered why or whether Self is really so much worse than, say, the soulless ensemble of characters in Succession. We thought that Money would not have worked at all from the outside: what interest we took in Self, and any glimmering of sympathy we had for him, was entirely a product of our immersion in his point of view, which in turn became a test for us of Amis’s experiment, of how far he could go without losing us. We did all read to the end (though we mostly admitted having done some strategic skimming when it just got to be too much)—and our conversation was definitely lively. I don’t expect any of us will read anything else by Amis, though. (Years ago, I remembered, we read his father’s Ending Up, which we enjoyed thoroughly.)

Our discussion wasn’t all negative. One member of the group noted that she felt John Self was a genuinely memorable, even iconic character, and we all grudgingly agreed that, hate him though we did, he was brilliantly executed: his voice (which is what Amis identified as the most important aspect of the novel, and fair enough) is distinctive and unforgettable. That we would like to forget it could, I suppose, be considered our problem, not the novel’s! Money also prompted a lot of discussion about the more general question of how far a novelist can or should go with an offensive character; we also considered why or whether Self is really so much worse than, say, the soulless ensemble of characters in Succession. We thought that Money would not have worked at all from the outside: what interest we took in Self, and any glimmering of sympathy we had for him, was entirely a product of our immersion in his point of view, which in turn became a test for us of Amis’s experiment, of how far he could go without losing us. We did all read to the end (though we mostly admitted having done some strategic skimming when it just got to be too much)—and our conversation was definitely lively. I don’t expect any of us will read anything else by Amis, though. (Years ago, I remembered, we read his father’s Ending Up, which we enjoyed thoroughly.)

Does she do this for Frances, the wary, lonely narrator of Look At Me? Do we—should we—find compassion in our hearts for her? There’s definitely something pathetic about her, as we follow her through her unexpected and initially life-affirming friendship with Nick and Alix Fraser, who are so much brighter and more beautiful and more exciting than she is:

Does she do this for Frances, the wary, lonely narrator of Look At Me? Do we—should we—find compassion in our hearts for her? There’s definitely something pathetic about her, as we follow her through her unexpected and initially life-affirming friendship with Nick and Alix Fraser, who are so much brighter and more beautiful and more exciting than she is: And yet Fanny’s motives and character also seem uncomfortable: she is manipulative, jealous, reticent to a fault. I’m not sure she’s meant to be an unreliable narrator, strictly speaking, but she’s certainly not a trustworthy one. She reminds me very much of Lucy Snowe in Villette, cast in the role of a spectator to life, showing strength and resilience but also stubbornness, bitterness, and even malice as she endures her marginalization and denies her own desires, even to herself. Just as Lucy watches Dr. John fall in love with Ginevra, insisting all the while that her own heart is untouched, so Fanny refuses to admit her love for James Anstey, only eventually to realize that if he did ever have romantic feelings for her (which I’m not sure of, really), the moment for claiming them has irrevocably passed. Lucy and Fanny also both endure an absolutely nightmarish walk through their city, so overcome with their own emotions that it makes them physically ill. Here’s Fanny, making her way home across London late at night after seeing James in love (or lust, anyway), with another woman:

And yet Fanny’s motives and character also seem uncomfortable: she is manipulative, jealous, reticent to a fault. I’m not sure she’s meant to be an unreliable narrator, strictly speaking, but she’s certainly not a trustworthy one. She reminds me very much of Lucy Snowe in Villette, cast in the role of a spectator to life, showing strength and resilience but also stubbornness, bitterness, and even malice as she endures her marginalization and denies her own desires, even to herself. Just as Lucy watches Dr. John fall in love with Ginevra, insisting all the while that her own heart is untouched, so Fanny refuses to admit her love for James Anstey, only eventually to realize that if he did ever have romantic feelings for her (which I’m not sure of, really), the moment for claiming them has irrevocably passed. Lucy and Fanny also both endure an absolutely nightmarish walk through their city, so overcome with their own emotions that it makes them physically ill. Here’s Fanny, making her way home across London late at night after seeing James in love (or lust, anyway), with another woman: Writing, for Fanny, is no balm, no refuge, only a retreat—though I think we are meant to take Look At Me as a sign that it can also be revenge. I find myself wondering (not knowing much at all about Brookner herself) how she talked about her own writing. The passage Trevor read is such a crushing statement about writing as the last resort of the outcast. I’m reminded of a passage from Hotel du Lac that I often think about, spoken by Edith, the “romantic fiction” writer who is the protagonist of the novel:

Writing, for Fanny, is no balm, no refuge, only a retreat—though I think we are meant to take Look At Me as a sign that it can also be revenge. I find myself wondering (not knowing much at all about Brookner herself) how she talked about her own writing. The passage Trevor read is such a crushing statement about writing as the last resort of the outcast. I’m reminded of a passage from Hotel du Lac that I often think about, spoken by Edith, the “romantic fiction” writer who is the protagonist of the novel: